Published on

February 6, 2023

Category

Features

Will Pritchard speaks with Adam Tovell and Isobel Clouter at the British Library about their wax cylinder archival project, True Echoes.

“Just imagine it’s the most expensive toilet roll in the world.”

Adam Tovell, the British Library’s head of technical services and processing, is talking through the necessarily delicate process of lifting a hundred-year-old phonograph cylinder from the slatted cardboard box that houses it.

We’re in the Sound Archive, in the labyrinthine basement of the British Library, and the soft wax that coats each cylinder, holding its light grooves, isn’t the only cause for care: these hollow tubes — which, to give Tovell his dues, do resemble a loo roll — contain some of the earliest sound recordings ever made. Replacement is not an option.

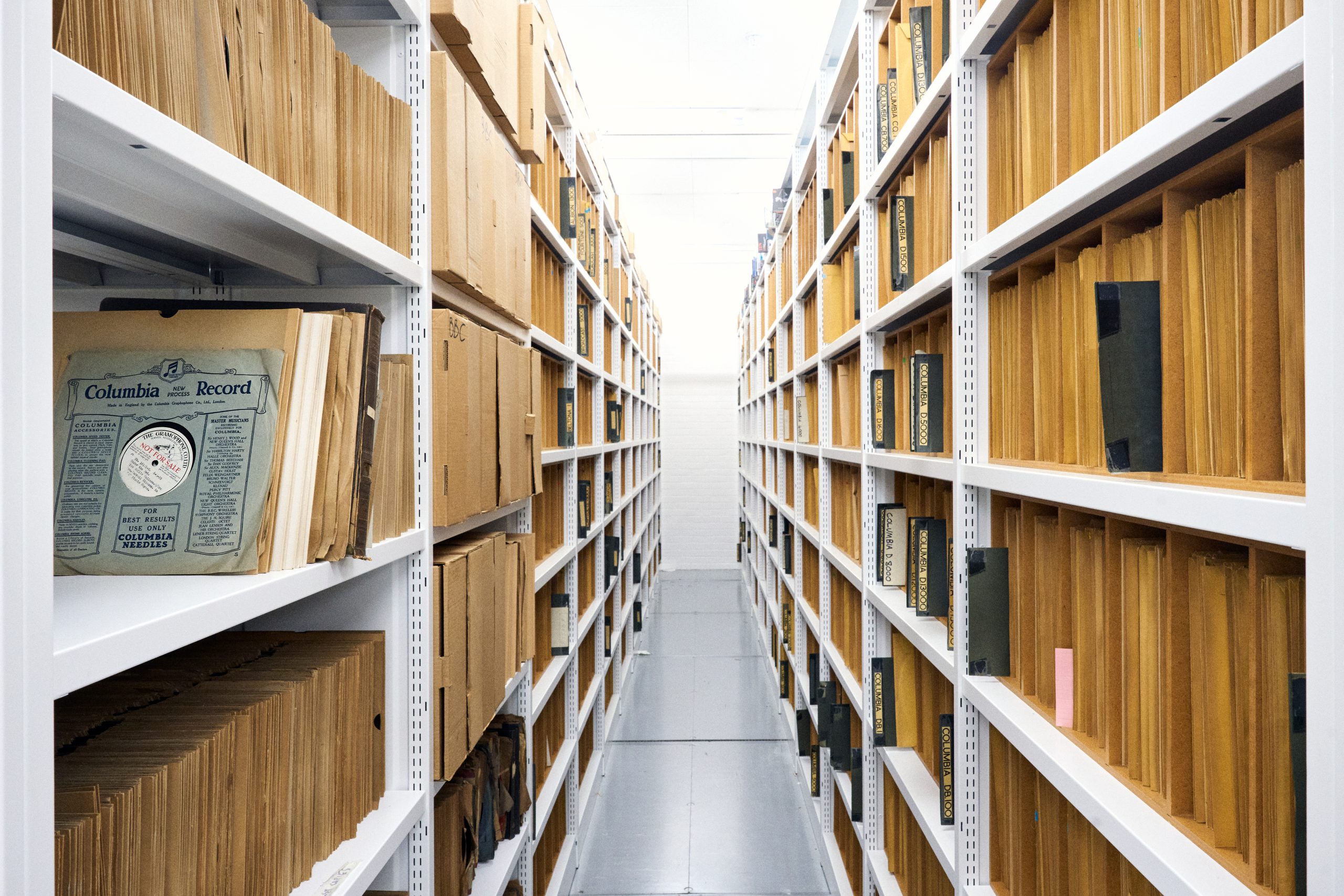

Above us, the occasional rumble of Victoria Line carriages cuts through the gentle hum of air conditioning that keeps the basement’s temperature within precise parameters of 16-20°C, and the humidity stable around the 50% mark. The lighting—soft white, brand new LEDs, zero UV emissions—flicks on as you reach each aisle.

“Because these cylinders have wax within them, including beeswax and other organic materials,” Tovell explains, gingerly rotating one blotchy, whitened example, “they are fragile and susceptible to humidity, which would encourage mould growth.” Mould, Tovell says, “literally eats away at the recording.” And these particular recordings, gathered from across Oceania over a period of 16 years between 1898 and 1924, contain not just sound, but history itself.

The process of digitising, labelling, and reconnecting the recordings with the places they were first made—from the villages of Simbo Island in the Solomons, to the outlying regions of Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea, and the earthy flecks of the Torres Strait—is uncovering musical cultures and oral traditions that otherwise risk being lost to the passage of time. Through the combined efforts of researchers based in the UK, Australia, Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea, and the Solomon Islands, under the broader title of True Echoes (the name of this ground-breaking, three-year project), the disparate threads of history are being retwined.

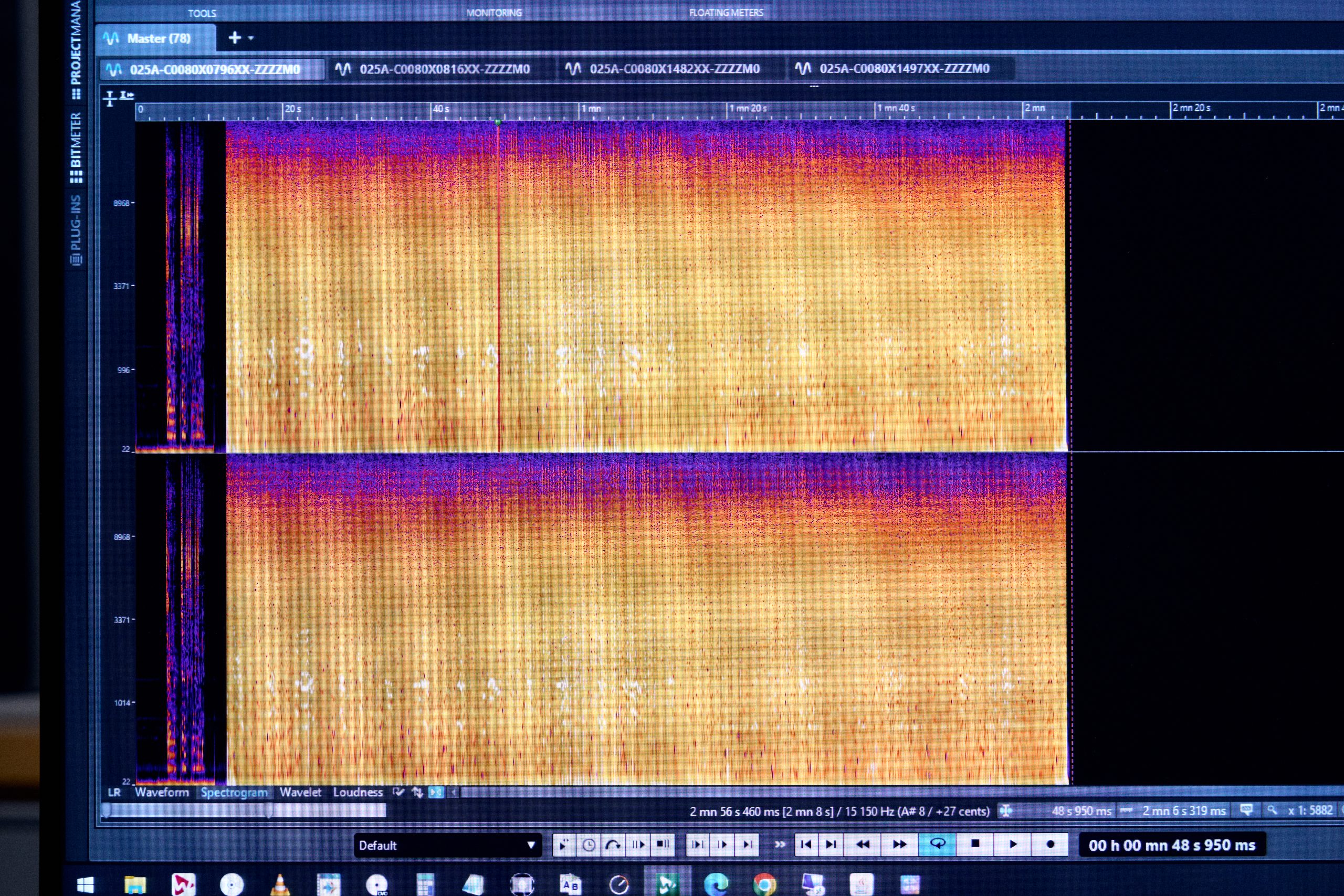

In all, the True Echoes project catalogues 266 total tubes, with 253 recordings pulled from the wax. They span stories, songs, dance performances, and speech: a naval band sings in the distance on one, women harmonise a three-part polyphony on another; there are flute duets named for local birds, and panpipe solos played through lengths of bamboo. Some are songs welcoming the new year, others offer warnings; there are ditties about canoes, and, of course, strains made for dancing. The results offer a varied and distinct glimpse of musical, archipelago life in the South Pacific. All are underpinned by the rhythmic thrum of each cylinder turning on the Library’s Pelec Systems Universal Cylinder Player, converting century-old memories into stretches of an orange and yellow waveform on the studio’s computer monitor.

Digitising the recordings has been a painstaking process. The cylinders, Tovell explains, sit at the apex of concern when it comes to both physical degradation (the creep of mould, for instance) and technological obsolescence (having access to the equipment needed to play or copy the recordings). Most of these digital copies were made in the 1990s, when the Universal Cylinder Player, one of just a handful that still exists worldwide, with its chunky diamond styli, was considered a cutting-edge piece of kit. The Library is currently purchasing new gear that will add capabilities such as laser reading, allowing engineers to work on converting broken or damaged cylinders and gleaning more from the recordings already ripped using the existing system.

Because the cylinder recordings were made using analogue, hand-cranked recording equipment, there are speed variations to contend with when playing them back. Recordists would use a tuning fork to give the starting note, so playback speed can be matched by lining up to the correct tone — or as close as possible: there’s nothing as simple as a choice between 33 1/3 and 45rpm here. Then, it’s a case of studiously adjusting the player’s tone arm to account for the variable depth of the grooves on each cylinder as playback progresses.

For quieter recordings, often those captured from afar, the grooves are barely visible, and the voices hardly audible. The inherent fragility of the soft wax coating (early commercial cylinders were in fact advertised as reusable, with outer layers able to be shaved off and written over as many as 100 times) only serves to raise the stakes: you only get a few shots at it before the risk of doing irreparable damage becomes too high.

Once digitised, the files are sifted and cleaned. They’re labelled and then meticulously analysed in a process that Isobel Clouter, curator of world and traditional music at the Library, as well as True Echoes’ principal investigator, likens to archaeology—just with fewer brushes, or bones. Working directly with partners in the Oceanic region, the goal is to link past with present.

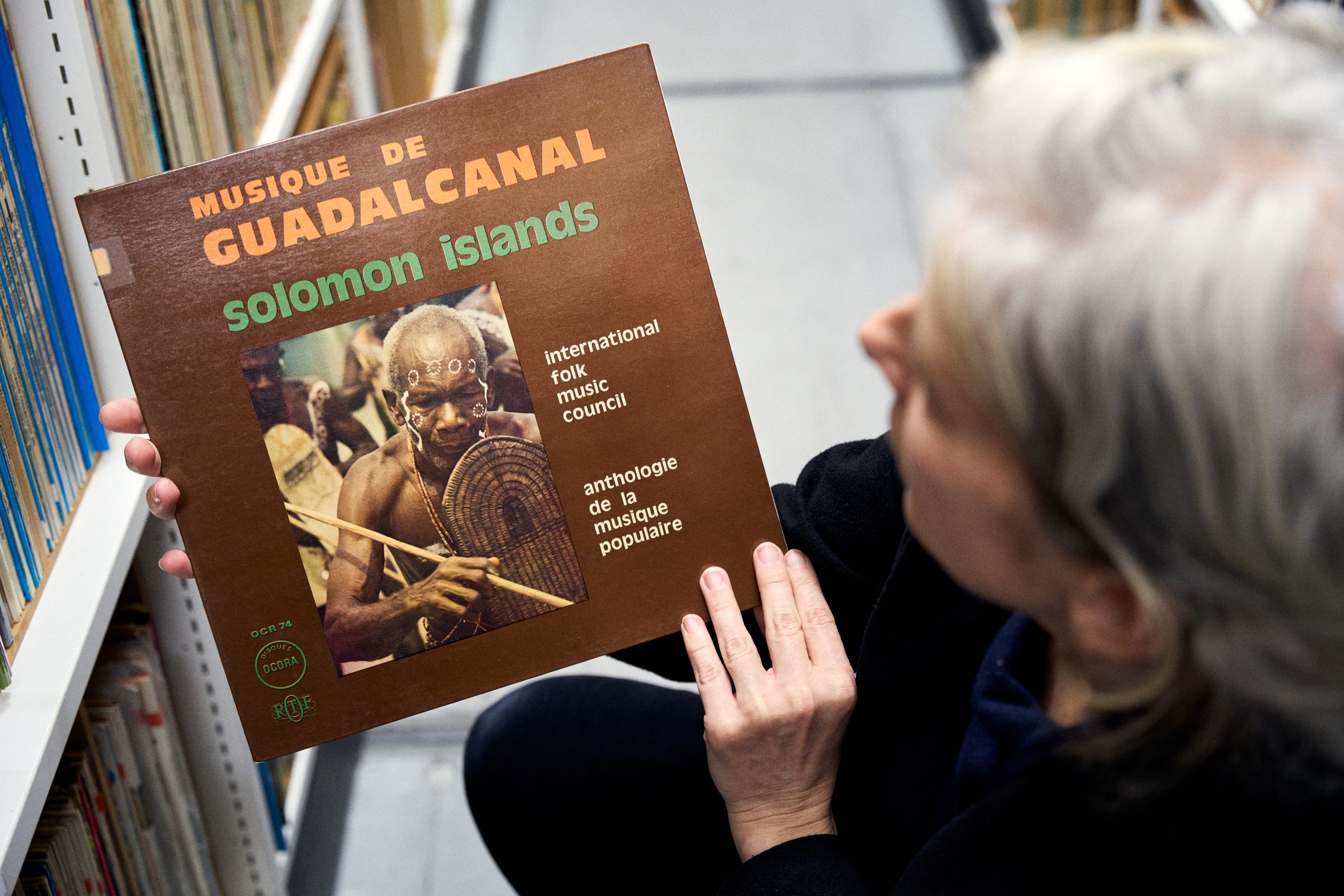

“It’s reconnection on three levels: between people and country, the music, and the meaning,” explains Clouter, whose enthusiasm brims over when she gets to flicking through the Sound Archives’ extensive collection of music from the South Pacific, her initial route, she explains, into this fascinating world.

“There was a universal response, from nearly everybody that was interviewed [about the recordings], of a sense of loss. This was a very common thing,” Clouter continues. “Loss meant different things to different people–and not necessarily a sense of loss of people, but a loss of something that was much bigger. So the majority of people were delighted to be able to reconnect.”

She pulls up a video on a tablet. Beneath the endless, balmy skies of the Solomon Islands, she’s there, meeting with elders, hearing performances of songs whose skeletons have survived the hand-me-down of oral tradition, and whose germinant versions can be heard via the cylinder recordings. But aside from the hymns that still filter out of churches established by missionaries in the late 1800s, these sonic connections with the past have become less accessible over the years.

With the cylinders too fragile to travel—or at least not without considerable risk—difficult to store, and even harder to coax sound from, the detailed cataloguing process of the True Echoes project has enabled the recordings to live on in more places, closer to their sources, and with a far greater degree of accessibility. This, Clouter says, is one of the guiding achievements of the project. Preloaded tablets allow access to the materials in places where Wi-Fi and cellular coverage are patchy (or non-existent).

Ownership is spread and shared, cultural ties made, and the meticulous work of those pioneering recordists and the people they were meeting is marked down for the record. Clouter describes an ongoing shift in which these songs can move from being merely performed as part of the process of remembering history to taking on a new present-day significance for the people living on the islands today — an effect, she says, that’s become visible in schools on the islands she visited.

Label-led projects with a shared ethos, like the Syrian Cassette Archive and the Majazz Project, while not reaching back as far into history as the Library’s funding (and technical gear) allow are achieving similar goals of reconnecting past and present. In turn, these discoveries and rediscoveries can inform new music, and reach new audiences—all with a degree of cultural sensitivity that avoids superficial, uncredited plundering. These are sensitivities that, Clouter says, run throughout the True Echoes project: it is not just the cylinders that should be handled with care.

This careful approach extends to how the team’s discoveries are presented, and when. COVID-19 lockdowns and travel restrictions stunted the project’s scope, which has meant some of the fieldwork through which recordings make their way back to their source in the islands hasn’t been completed yet—so these clips haven’t been made public yet. Elsewhere, materials that might be considered “secret, sacred or sensitive, or have traditional protocols around who can access them” are flagged and the website itself comes with a specific warning for Torres Strait Islander peoples that the site “contains images, voices and names of deceased persons.”

Back in the basement, Clouter has mastered lifting the cylinders from their cardboard chambers. Even now, new details reveal themselves: worn grooves, warnings of mould, undeciphered labels on scraps of paper. What could “SHAVED BLANKS”—stamped in royal blue ink on the top of one container—mean? Tovell says it’s a while since he’s been down here: encountering the never-ending shelves serves only to remind him of the scale of the challenge that preserving and conserving all of this material presents. It’s easy to get lost here.

Clouter is perhaps more sanguine. When she first visited the archive many years ago, she says it felt like being able to walk into her own enormous record collection. The thought embarrasses her now. As time has passed, she’s come to see the value of this space, and the tiers of formats old, new, and obsolete that it holds, in a different way. The real value, she says, is in finding ways to make these objects more visible, more accessible, and more audible to the communities they represent: so that the process of reconnection—between people, music, and meaning—can continue to bear forth.