Published on

July 27, 2022

Category

Features

Tracing the rich, sometimes fractious history of musicians and photographers.

John Berger, one of the most influential art critics of his generation, once wrote that “photography, because it stops the flow of life, is always flirting with death.” Which makes it somewhat ironic that, since the camera’s inception, photography has helped both birth and nurture the development of countless musicians and their surrounding scenes.

More than just a documentary device, the camera has helped artists ascend into the realm of almost god-like figures, with their glittering images leaving a tangled web of mythos, desire, and deception in their wake.

This dynamic has been transformed over the years, impacted by shifting ideas of authenticity, the disruption of traditional photographic practices by social media and camera phones, and the development of the music industry itself. A new exhibition curated by Mark Beasley at New York’s Pace Gallery, titled Studio To Stage, seeks to unpick these shifts.

The show journeys from NYC’s ‘50s jazz scene to the leather-bound punks of ‘70s Britain, the pioneers of early ‘80s hip-hop, and all the way up to present-day provocateurs like MIA and Chief Keef. By tying together an eclectic tapestry of genres, periods, and artists, the exhibition interrogates the ways in which we desire to view and consume our musical icons.

Susan Sontag wrote that “to photograph people is to violate them.” The relationship between photographer and subject, she and others believed, is an antagonistic one, turning “people into objects that can be symbolically possessed.” There is certainly a degree of truth to this. For fans, photographs offer a way to feel closer to their idols: adorning their bedroom walls with posters and memorabilia, dedicating hours to curating ‘stan’ accounts on social media.

However, many photographers have strived to challenge the idea that photos simply objectify their subjects, instead aspiring to capture more authentic moments in their work.

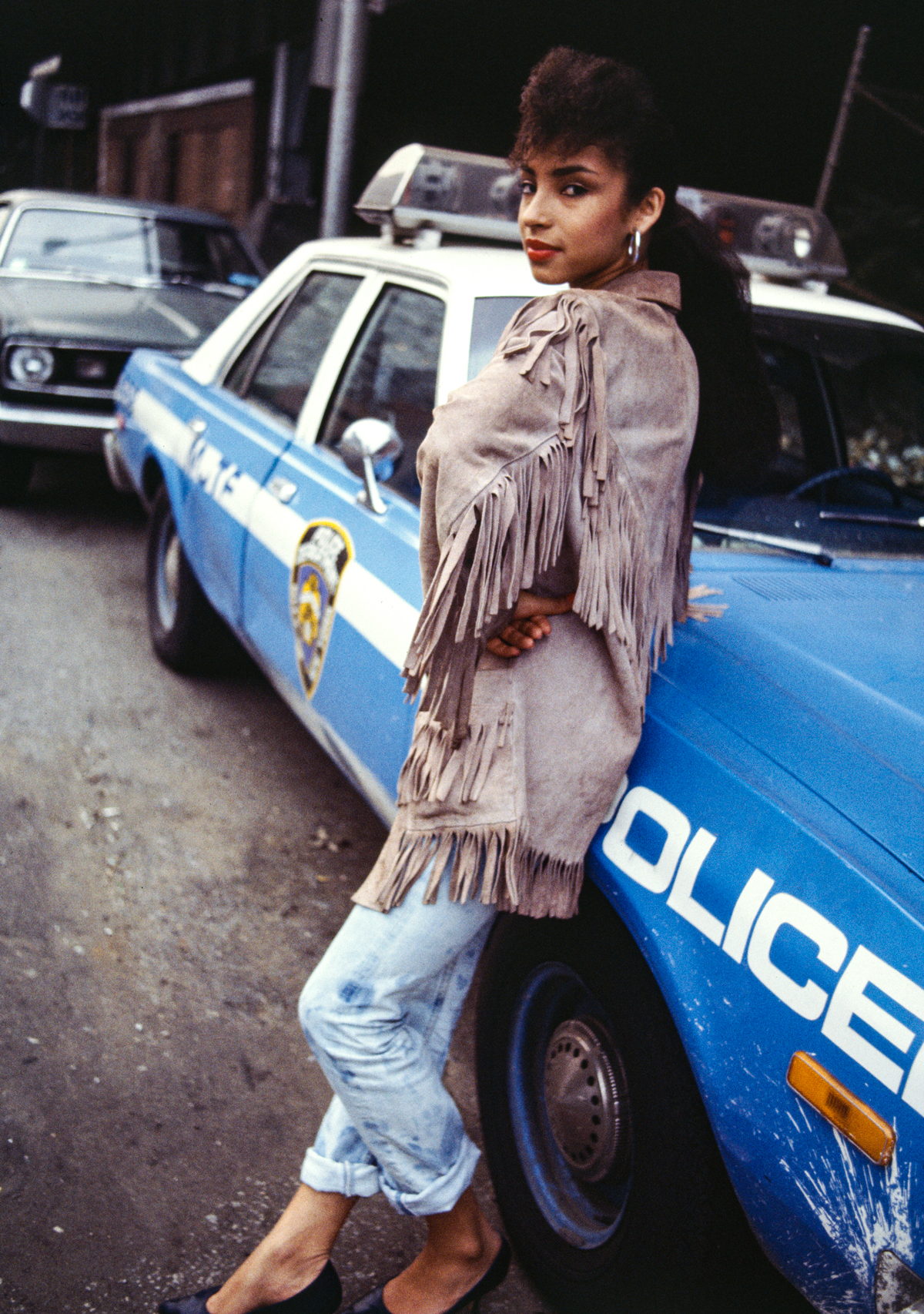

For photographer Janette Beckman, building trust with her subjects is crucial to producing authentic portraits. For her, “every portrait is a collaboration between me and the subject.” Based not on possession but mutual respect, her photos of Sade hanging out in NYC’s Lower East Side, or Run DMC on the street where they lived, offer intimate glimpses into the musicians’ worlds. Even now, she still shuns tools like Photoshop, asserting that her favourite way to photograph someone is walking around the streets of their neighbourhood.

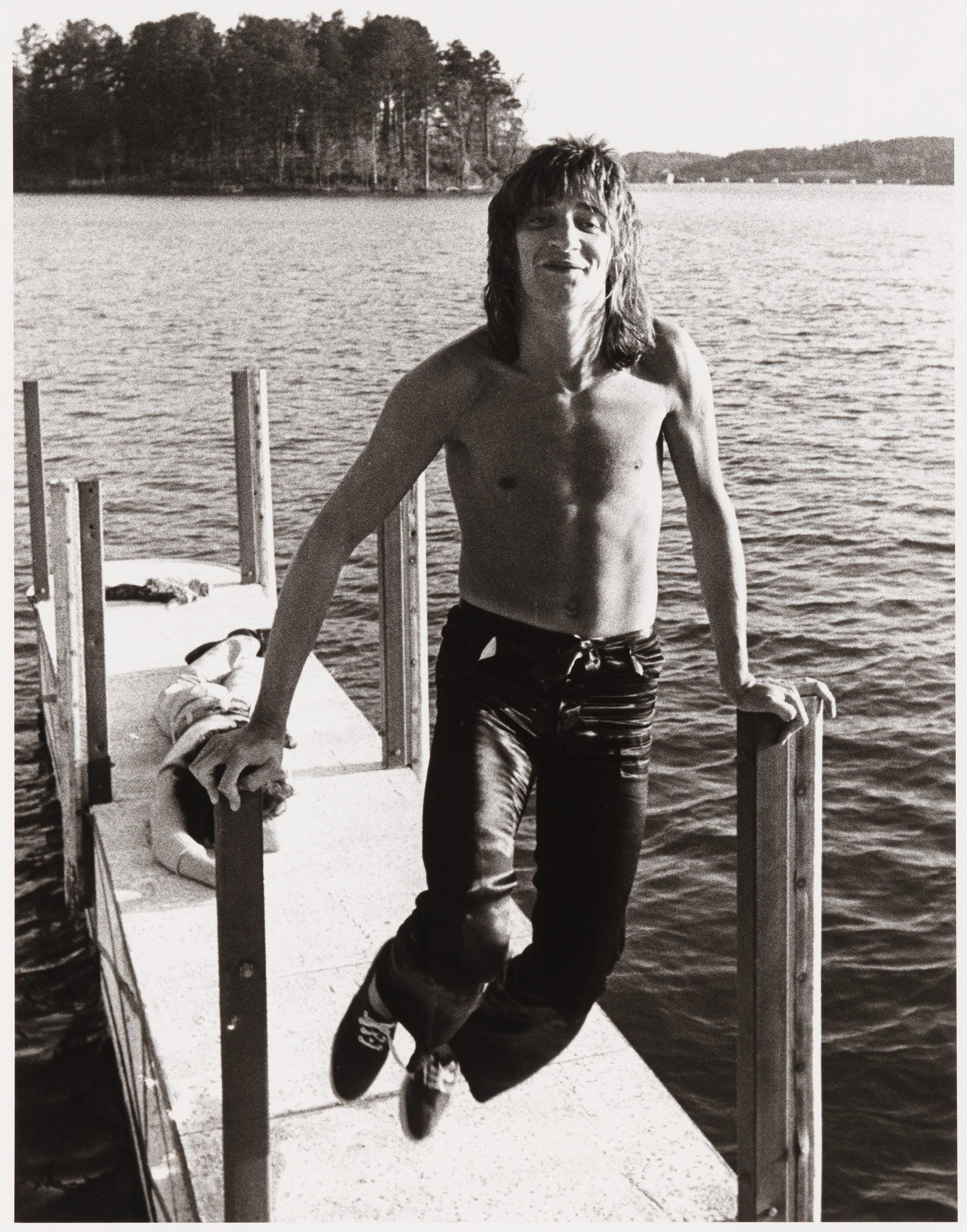

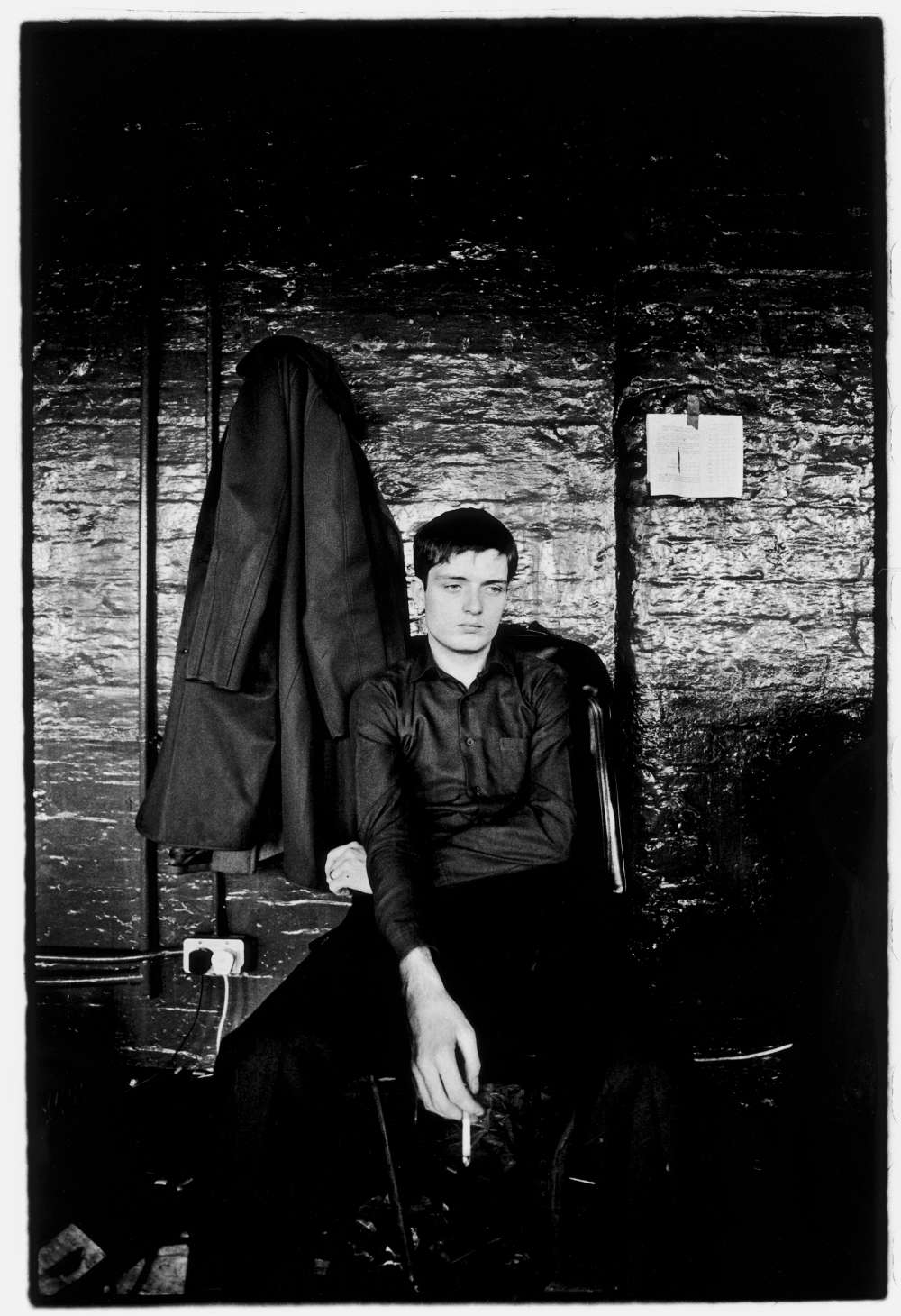

The same is true of Kevin Cummins’ photos of Ian Curtis and David Bowie – the ceremonial armour of Bowie’s costumes and makeup discarded – or Peter Hujar’s shot of Rod Stewart larking on a dock. These pictures reveal the camera’s ability to draw out the vulnerability of an artist, painting them, simply, as people. Interesting, often extraordinary people, but people nonetheless.

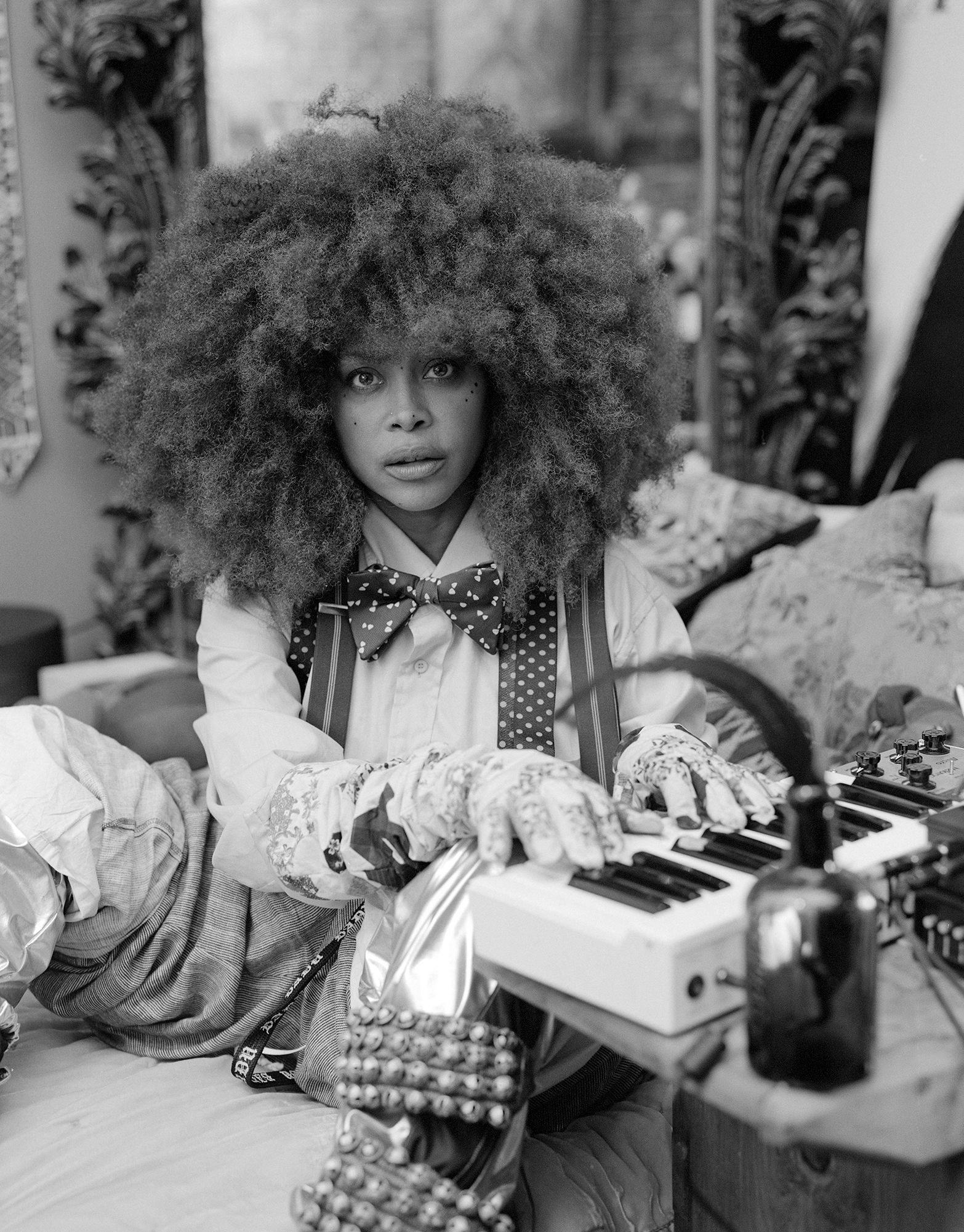

Today, this level of intimacy can feel rare. High-production studio shoots have become the norm for major music magazines, with hyper-stylised images often feeling closer to fashion editorials. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing: photographers and editors are becoming increasingly innovative and bold in their image making, emboldened by many stars’ willingness to experiment with aesthetics.

However, in Beckman’s eyes, the corporatisation of the music industry has made forming genuine connections between photographer and subject much more difficult. “For most of the shoots, it was just me and the artist, no art directors, stylists, managers, or PR folk. It was easy to build trust and work with [them] to create the portraits,” she recalls. “These days it’s more complicated; there are usually more ‘cooks in the kitchen’.”

It’s not uncommon in the modern era for artists to demand strict control over their own image. In 2013, for example, Beyoncé banned press photographers from her Mrs Carter world tour, in an apparent backlash against a series of “unflattering” photos from her performance at that year’s Super Bowl. The power dynamic appears to have shifted.

But in achieving the ‘perfect’ image – which generally translates to well-lit and posed – there’s a risk of losing the kinetic rawness seen in Cummins’ picture of The Sex Pistols at Wolverhampton’s Club Lafayette, or the sleazy hedonism of Nick Waplington’s dispatches from NYC’s The Sound Factory.

As music photography practices have evolved, many musicians have become their own surveyors. Once subjected – for better or worse – to the gaze of the photographer, they are now able to simultaneously fill the otherwise dissonant roles of photographer and subject.

The COVID-19 pandemic and its subsequent lockdowns helped to accelerate this trend. Charli XCX shot a self-portrait for the artwork of her 2020 album How I’m Feeling Now, laid back in underwear in the pointedly intimate setting of her bed; reggaetonero Bad Bunny, meanwhile, was photographed by his girlfriend Gabriela Berlingeri for the cover of Rolling Stone, his mask quite literally being pulled off.

The desire for these ‘intimate’ images is perhaps explained by the art critic Fisun Guner’s theory that “to many, the artist is an exotic creature whose mystery is still to be fully penetrated.” As we gaze upon the seemingly vulnerable and exposed forms of our idols, it can feel like we really do know them.

Smartphones and social media have made musicians more photographed than ever before. Janette Beckman sees this as a positive thing for photographers, who now have the ability to instantly share their work with people across the globe. But for musicians, it can represent an added strain.

In an essay for The Guardian spotlighting the current trend for record labels to demand TikTok content from their artists, English singer-songwriter Self Esteem wrote: “It can feel quite degrading – not to mention psychologically dangerous – to tie your only chance of success to your ability to perform the kind of personality that plays well online, and not your work.”

Arguably, the ‘highlight reel’ nature of social media has eroded authenticity. Exposed to so many eyes, artists (understandably) grow increasingly protective and controlling of their image and how they’re perceived. The clear divide between subject and object in traditional structures of photography can offer a relief from this, as well as providing a distinct barrier from one’s audience. And the results, as Studio To Stage so meticulously documents, are uniquely valuable.

When photographers are given the chance to work closely with musicians for extended periods of time, genuine, intimate, revealing moments of openness and authenticity are able to bloom. As American photographer Rahim Fortune says: “a true documentary photograph will always have a special place in music and could never be replaced by smartphone technology.”

Studio To Stage will run from the 29th June until August 19th at Pace New York.

Banner photo: Kevin Cummins, David Bowie in front of Tea & Sympathy in New York City, 10 January 1997 © Kevin Cummins, courtesy of Pace Gallery.