Published on

December 1, 2015

Category

Features

An unforgettable mix of afro, reggae, jazz and funk, Cymande’s debut album captured the the black experience in ’70s London and inspired a generation of hip hop producers across the pond. With their first new album in four decades out now, Liam Izod digs out the roots of this extraordinary record and traces its branches all the way to Grandmaster Flash, De La Soul and Fugees.

Words: Liam Izod

Britain in 1972: Ted Heath; the Troubles; T-Rex in the charts. There is little room in the popular memory of the period for Cymande, a group of Caribbean-born, Brixton-based musicians, who released their self-titled debut album that year. Cymande’s sound was hard to categorise and remains so; an intangible alloy of reggae-inflected soul grooves and tribal poly-rhythms. In 1970s Britain they sank with barely a trace. Instead Cymande’s quixotic calypso resonated in the U.S, where the band burnt bright and briefly until their break-up in 1975.

That might have been it for Cymande, were it not for their rediscovery by the pioneers of hip hop. DJs Kool Herc and Grandmaster Flash excavated Cymande’s bass lines and grooves, deploying them as hooks and breakbeats in their sets. By the end of the 1990s Cymande’s back catalogue, in particular their debut album, was the worst kept secret of crate diggers from L.A to Paris. They stand today as one of the most sampled black British bands ever, cropping up on hip hop, house, and dance 12″s the world over.

Even upon its original release Cymande was a Rosetta Stone of a record, from which the grammar and history of black music could be decoded. The percussive patter of antique African rhythms melds with patois gospel grooves and bluesy funk riffs. The record’s afterlife as a sample library lends it another dimension, allowing the listener to travel tardis-like through the development of black music, and the social experience to which it gave voice.

Unpacking the album’s musical references provides a sobering testament to the experience of black and ethnic minority communities in the U.S. and the U.K. But listening to Cymande is no academic exercise; the album’s jazz infused Rasta-rhythms are organic and undeniably danceable. You can find Cymande’s heirs among today’s genre benders. Guardian Critic John L Waters described funk fusion men-of-the-moment Snarky Puppy as having ‘absorbed and reinvented almost the entire history of jazz fusion.’ Add the history of reggae, calypso, and a strong dose of Rastafarian theology and you’re close to Cymande’s concoction.

UK R&B impresario John Schroeder strode into a Soho strip club in 1971 intending to audition some hopefuls for his newly minted label Alaska Records. He was distracted by some unusual grooves emanating from the basement and, foregoing the audition, followed his ears to find an exuberant crowd tuned in to Cymande’s funk-rock vibes. Within weeks Schroeder had committed them to vinyl, cutting four demos, among them bouncy funk-reggae number ‘The Message’.

Schroeder took the demos to industry trade fair Midem in Cannes, where he played them to U.S executive Marvin Schlachter. Schlachter was so impressed that when Schroeder returned to Britain he walked back through customs with a briefcase stuffed with enough cash to record Cymande’s debut album; nothing to declare but the funk. Schlachter released Cymande in the U.S on Janus records, a sub-division of legendary R&B label Chess Records, which had housed blues legends such as Howlin’ Wolf and Etta James. ‘The Message’ was chosen as Cymande’s lead single and it scored an unexpected top 20 hit on the U.S R&B charts. A national tour in support of soul supremo Al Green followed, during which Cymande became the first British band to play the legendary Harlem Apollo.

Why did Cymande resonate with U.S audiences? Their unusual but infectious grooves played a huge part. Schroeder recalls a gig in Philadelphia where the audience were inspired to join in, tapping out time with forks and spoons whilst dancing on the tables. At Cymande’s heart was a partnership between guitarist Patrick Patterson and bassist Steve Scipio, both of whom originally hailed from Guyana. Prior to Cymande the duo had played in a jazz fusion band called Meta, whose Nigerian drummer schooled them in odd time signatures and traditional African rhythms. With their own outfit, Patterson and Scipio added the grooves of U.S R&B and British blues-rock to the cocktail, creating something they dubbed ‘Nyah Rock’. ‘Nyah’ referenced the Nyahbinghi Mansion of the Rastafarian faith, whose ritual rhythms underpinned Cymande’s sound.

On the album’s second single ‘Bra’ Patterson’s guitar burbles Hendrix-like accompanied by Scipio’s Motown tinged bass. ‘Bra’, slang for ‘Brother’, reflects Cymande’s Rastafarian philosophy. Whilst the verse catalogues injustices – “They might have said we’re lying/No matter how hard we try” – the chorus jubilantly exclaims, “But it’s alright, we can still go on”.

The track owes something to U.S soul ambassador Curtis Mayfield’s paean to positivity ‘Move on Up’, which was released two years earlier in 1970. Instead of the urgency of Curtis’ exhortations, there was something distinctly relaxed and even resigned about the lyrical messages on Cymande. ‘Getting it Back’ laments “I guess I’m going down”, with little sense there is anything that could be done about it.

By the time of Cymande’s resurrection in the late 1980s, the message had changed. Grandmaster Flash released his far better known ‘The Message’ in 1982. Its commentary on desperation and double digit inflation revealed a community low on the faith that had sustained Cymande. Whilst Cymande’s debut album gave hip hop artists access to grooves steeped in the history of black music, it also contained a message in need of an update.

‘Problems’, an early Wu Tang Clan demo from 1992 sampled ‘Dove’, a sprawling instrumental anthem to peace built around a Santana-like guitar riff. The Wu Tang Clan clipped ‘Dove’s’ wings. The signature guitar riff is truncated and looped, giving it a maddening quality that RZA uses to explicitly spike the vibe of the upbeat original. He raps of hopelessness – “Things would change, I thought that at first, right? Time goes on, things got worse”, and its consequences, “I was a good citizen now I’m a leech.”

In 1992 black musicians were a community no longer content to keep on pushing. In the same year, the acquittal of the white police officers who had been filmed beating Rodney King half to death sparked the L.A riots. A year after the riots The Coup, an L.A based outfit known for their political hip hop, released their playfully provocative debut Kill Your Landlord.

‘I Ain’t the Nigga’ uses Cymande’s ‘The Message’ as the basis for a searing commentary on race in the U.S that has lost none of its relevance. The Coup front-man Boots Riley raps a defiant plea, “You wanna race for the trigger? I ain’t the one, I ain’t the nigga”. In 1990s America, black lives did not seem to matter, and Cymande’s Rasta optimism, and even Curtis Mayfield’s dignified Civil Rights sermons, looked hopelessly naïve.

Hip hop visionaries De La Soul offered a more positive alternative to the understandably disillusioned and angry currents of mainstream hip hop. ‘Change in Speak’, a track from their 1989 masterpiece 3 Feet High and Rising sampled Cymande’s ‘Bra’, borrowing its jubilant horn lines to support the proclamation, “you are now dancing to the new soul”. In making this claim De La Soul invoked the evolution of black music from the original soul music of the 1960s and ‘70s.

De La Soul’s exhortation to dance towards enlightenment is akin to Cymande’s Rastafarian philosophy, but just as De La Soul’s chilled jams proved out-of-kilter with the hip hop mainstream, their more faithful interpretation of Cymande was the exception not the rule. By 1996, even the Fugees – who like De La Soul had a reputation for sensitivity – employed a Cymande sample on an explicitly militaristic track. ‘The Score’ paired Paterson’s guitar riff on ‘Dove’ with a refrain inciting a march to war, “left, right, left, right”.

Cymande’s reinterpretation by hip hop artists in the 1980s and 1990s changed the original album itself. The 1972 release of Cymande led with ‘Zion I’, a funked-up hymn to Rastafarianism. On the 1993 U.S re-release on compact disc, ‘Zion I’ was shunted to the end. The whole album was re-ordered to feature the tracks that were most popular with samplers. ‘The Message’, ‘Dove’, and ‘Bra’ were all amongst the first four tracks. Track two was ‘Brothers on the Slide’, a song originally from Cymande’s third album Promised Heights, released in 1974.

Over a guitar riff that could have provided inspiration for some of the Red Hot Chili Pepper’s hits, ‘Brothers on the Slide’ offers a downbeat commentary on the plight of black brothers. In a Curtis Mayfield-like falsetto the vocalist declares “You can’t win so you know you must lose”. The sentiment is a far cry from Mayfield’s ‘60s civil rights anthem ‘We’re a Winner’. With this treatment, Cymande’s debut album takes on the quality of a palimpsest, its original messages reinterpreted and rewritten by later scribes.

One element has remained consistent throughout the shifts in the reception of Cymande’s debut album. A clue can be found on the Coup’s ‘I Ain’t the Nigga’, which paired its Cymande sample with an excerpt from Big Daddy Kane’s rap on Kool G Rap and DJ Polo’s 1990 single ‘Erase Racism’. The refrain “If I’m a slave then I’m a slave to the rhythm” is repeated throughout. This statement unifies the disparate messages to say something that has been true of black music since the chain gang holler of the early blues; if there’s a means of subverting mistreatment, it is through music and movement. Whilst Cymande’s ‘message’ may have evolved, their enduring appeal comes back to that Philadelphia crowd and their spontaneous cutlery calypso. They’ve got the funk.

Cymande’s new album A Simple Act Of Faith is out now via Cherry Red Records.

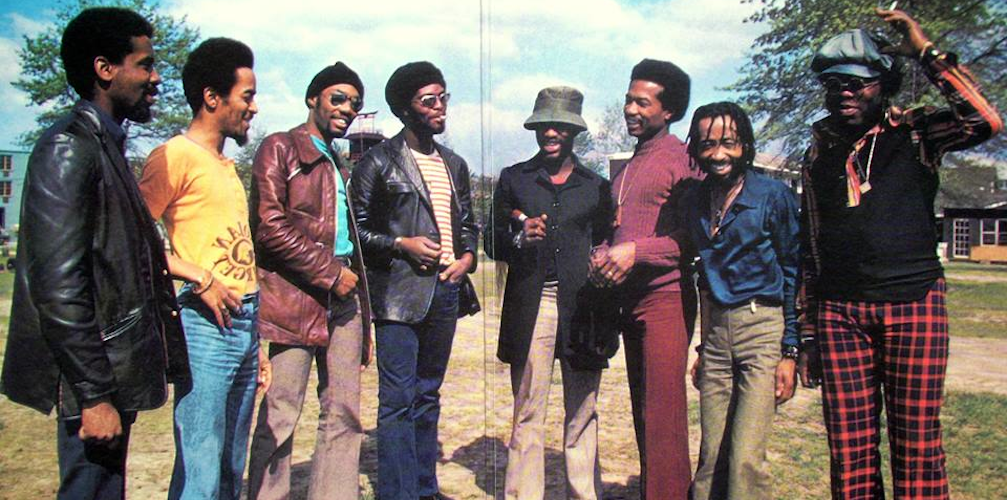

Record photos: Michael Wilkin