Published on

September 1, 2015

Category

Features

Started by a twelve year old Greg Ginn as a mail-order business selling WWII surplus radio equipment, Solid State Transmitters shaped the underground sound of US hardcore and set the foundations for grunge and punk rock before imploding under the weight of its own reputation. Nick Soulsby remembers the good times.

Words: Nick Soulsby

SST Records, at its peak, dominated the U.S. underground scene of the ’80s. Kurt Cobain, a scrawny teenager discovering punk in 1983 would write a now famous favourite albums list nearly a decade later on which there were more releases from SST or SST-affiliated bands than from any single artist, label or scene. This is a testament to how thoroughly SST defined the era in the hearts and minds of a generation of hardcore-lovers, those already moving on and the teenage generation that would forge the indie and alternative scene of the next decade.

Greg Ginn was already into his thirties, his maturity bringing with it the self-confidence and experience needed to set up the label, to ensure half-decent production and to track down the contacts needed to print records. An original firestarter, Ginn’s label – while centered around hardcore superstars Black Flag – became synonymous with an expansive vision in which few releases sounded the same, in which multiple takes on the punk template coexisted.

The label was a fair reflection of the man at its heart. A rapaciously creative soul, Ginn would dispense with collaborators and approaches at rapid speed under the Black Flag logo as his desires moved on; the band’s albums almost all sound significantly different. Soon a single band wasn’t enough and he was already playing in a variety of projects before Black Flag reached their denouement. With eight LPs and eight EPs and two compilations released on SST in the ’80s, Black Flag was a vital and dependable revenue generator which allowed the label to expand and to take chances.

Image: Black Flag / SST

Given Ginn’s catholic musical tastes, expanding that core of bands would lead the label to draw in bands who wanted something more than straight forward hardcore music. Minutemen, Meat Puppets, Saccharine Trust and Hüsker Dü all became semi-legendary with their inventive new ways of twisting the punk approach. And yet Ginn’s liking for louder-harder-faster sonic extremity meant SST would also provide releases to metal or metal-orientated bands like Stains, Würm, Saint Vitus and Overkill L.A. in the early years of SST. While this aspect of the scene hasn’t gained critical respect it was certainly prominent as part of the label’s inclinations.

SST had to learn fast. Punk labels printed in the hundreds, maybe the low thousands. Success on a grander scale – as SST found with Hüsker Dü – meant having to try and ramp up production capacity at short notice or risk losing momentum by letting releases go out of print. Losing the core of the label between 1985 and ’86 presented a financial and a reputational challenge; what was SST once Black Flag broke up, Minutemen ended in the tragic death of D.Boon and Hüsker Dü left for a major label?

Any label would have difficulty forging a path after the demise of the marquee bands that made its name, and SST took a fair shot at surviving the abrupt rise and fall that was the norm for underground or punk labels. Part of the survival strategy was to bring on board established bands with existing followings; both Sonic Youth and Bad Brains had releases on SST in 1986 while Dinosaur Jr. already had the inklings of a reputation after a first album on Homestead.

Reaching for tried-and-tested bands also meant continuing to milk existing SST success stories with live releases – from Black Flag, the Minutemen, Sonic Youth for example – plus retrospectives like Zoogz Rift’s Looser Than Clams, Saccharine Trust’s The Sacramental Element or the Post-Mersh series from the Minutemen. In addition, having only released one multi-artist compilation in the label’s first six years, SST topped up the catalogue by releasing eight in three years, while purchasing New Alliance Records allowing them to re-release back catalogue material by the Minutemen and the Descendants.

In the four years between 1978-1982 there had been a mere twelve EPs and LPs on SST. By 1990 the SST catalogue had topped 250. From 1986 onward the label was flinging material at the wall with abandon. The logic of it had a ‘law of the jungle’ simplicity; no label can predict the next smash hit or where the zeitgeist will go. So, instead of staking all on a handful of albums a year, the retreads – reissues – re-releases – leftover compilations and established bands would subsidise a scattergun spray of other artists. The label would then cull the dross and pump more support into the winners. As if this wasn’t enough, Ginn kept the New Alliance label name and began using it to pump out avant-garde jazz and rock releases, then set up Cruz Records to slam out more grunge and punk releases.

However, the breadth of SST’s musical horizons robbed it of a defined identity beyond ‘Corporate Rock Still Sucks’. SST had become as ubiquitous as a barcode; a small stamp that just happened to be on one or another record rather than a clear statement of identity. It was financially near impossible for any fan to buy the eighty releases SST put out in 1988 alone.

The late ’80s SST catalogue has some points of interest, but few genuine classics. Similarly, trying to maintain this hyperactive pace seemed to take its toll on the administration of the label. Several artists complained of not being paid or of what they saw as untrustworthy accounting. Both the Meat Puppets and Keith Morris took SST to court claiming they were owed money. The personal disputes with Hüsker Dü put pay to one of the label’s newer jewels with Sonic Youth and Dinosaur Jr. following. By 1990 the fire had gone out, the stream of releases dried up and the label purged a lot of the most jarring diversions. It wasn’t enough though. Many of the bands releasing albums on SST in the early ’90s had been on the label for years and, despite their merits or otherwise, had little chance of breaking into mass consciousness. The Leaving Trains, the Flesh Eaters, Trotsky Icepick, Volcano Suns… Forgotten names now.

Ginn’s loyalty to friends like H.R., formerly of Bad Brains, Pat Smear, formerly of the Germs, or Roger Miller, formerly of Mission of Burma, was to his credit, but newer punk labels like Epitaph had quietly begun to sell substantial numbers of records and it would be LA pop-punk bands like Green Day, Offspring and Bad Religion who caught the next wave for punk music. A major label battle with a former SST band Negativland, plus the bankruptcy of the label’s distributor seemed to finish SST off as a forward-looking concern though the label has run a low-key release schedule in recent years.

In its time SST was a true original, so rather than lamenting the blazing finale, we’d like to celebrate ten of SST’s best. Listen to tracks from all ten records in this playlist or individually as you read.

Black Flag

Damaged

(1981)

Diversity was the key to SST Records and Black Flag’s signature album delivers it in spades. Some songs – ‘Spray Paint’ for instance – rip past in a hardcore minute of viciousness, other’s – ‘Six Pack’ or ‘TV Party’ – keep the momentum but add the fun of being a live fast, die young teen over on the west coast. The band had strong ties to the Washington DC punk scene of the time and retained the focus on social realism, but leavened the po-faced seriousness with a more measured day-to-day reality. While the vocals remain firmly in the gargling glass school and most songs keep the frenetically-paced guitar chords the band even dared to slow down every now and again giving inklings of something beyond louder-harder-faster.

Saccharine Trust

Paganicons

(1981)

A common complaint in the U.K. is that too many people try to sound American. Well, this was one band who embraced the Brit tone and dragged it by the scruff of its neck into the rough and tumble of the U.S. scene of ‘81. There are so many odd touches to this sixteen minute album, so many innovations to the formula. The very first song kicks off with the nearest thing to a straight hardcore riff on the whole album – but it’s a suckerpunch. Other songs take in harmonized moans, cracked spoken word, stop-start post-punk verses, voice and guitar galloping and tumbling over one another before sickly twisted words about “success and failure.” This is an awesome way to spend a quarter of an hour again and again and again.

The Dicks

Kill from the Heart

(1983)

A band who knew what it meant to belly-laugh, the Dicks had a way for adding chuckles. The vocal delivery hews close to rockabilly; full throated, mealy-mouthed, spluttering growls and roars of sheer excitement. There was plenty amateurish about the band’s technique but take a look at the guitar work on a song like ‘No Nazi Friend’ and see how well it suited them. A ragged desecration of Hendrix’ ‘Purple Haze’ is carried off with a devilish charm and the band even make lines like “from the heart… You need to be shot,” sound like robustly inane comedy.

Meat Puppets

II

(1984)

The Kirkwood brothers hit upon a winning formula with Meat Puppets II. Curt Kirkwood has a gift for capturing a succinct scene or sentiment in crystal-sharp detail – likewise the frayed and fried tone of his voice is intrinsic to the spirit of each song, a weary traveler recounting a moment. Musically the album wraps together a disparate parcel of punk velocity, country twang, southern-fried rock into a coherent whole. The band aren’t afraid of showing off an ability to shred and scratch the guitar in ways foreign to hardcore. It’s a welcoming album foreshadowing the Meat Puppets’ eventual dive into full-on indie as well as containing three tracks Kurt Cobain insisted on showcasing during the famous MTV Unplugged in New York performance.

Minutemen

Double Nickels on the Dime

(1984)

Forty-three songs in seventy-four minutes; the Minutemen were real givers on this album. The scratchy guitar tone and prominently funky bass are the signatures across a blast of swift sharp songs which sound far cleaner on record than I’m sure they did in the broiled air of a packed club. The band liked to amuse themselves with lengthy or thoughtful song titles – for example ‘The Roar of the Masses Could be Farts’, or ‘Political Song for Michael Jackson to Sing’ – revealing a sense of humour amid the chorus-less lyrics. Words are declaimed, entire dissertations line by line.

Hüsker Dü

Flip Your Wig

(1985)

The first band to crack the formula of re-attaching the bounce of new wave to the harder roar of ’80s hardcore, Hüsker Dü were on their way to a major label deal. Saying that Hüsker Dü are recognizably incorporating pop into their formula doesn’t mean there’s not real muscle at the core of these tracks. They simply wedded the punch and heft of an overdriven guitar to melodies, wedded real riffs into verse-chorus-verse traditional song structures and built three minute songs instead of punk’s brief growls. Having two writers of memorable and catchy songs certainly aided the band’s rise as did their work rate, they poured out albums in the mid-’80s but this is one of the best and comes right before their mildly acrimonious departure from the SST label.

Bad Brains

I Against I

(1986)

Years earlier Ian MacKaye barked out a call to arms; “at least I’m fucking trying.” By 1986 Bad Brains were an institution, a band with an erratic yet still exciting reputation. They proved it by moving to SST and – for better or worse – incorporated metal into their already tangled musical vibe. If you can get past the squealing solos there’s a lot of talented song writing here. Loyalty to these ambiguous icons of the scene was understandable but listening to what sounds, essentially, like a mainstream production job running over the juddering rock guitar, it’s clear the church of SST had stretched catholic taste to popping point. Still I defy anyone not to find ‘Re-Ignition’ catchy as hell. That’s the truth, at least these guys were trying to make something more than the same album over and over.

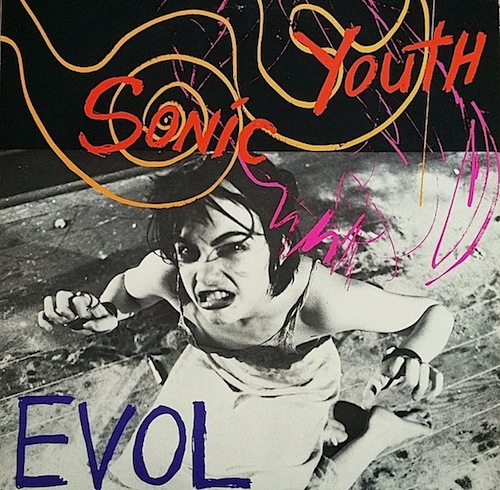

Sonic Youth

Evol

(1986)

Notorious for a percussive approach to the guitar and for drumsticks wedged in strings, Sonic Youth switched direction and embraced a mutilated vision of rock. The result was the band’s first all-out attack on the rock anthem variously known as ‘Madonna, Sean and Me,’ or ‘Expressway to Your Skull’ – a blitz of a track paving the way to the takeover of the rock mainstream and the chart death of hard rock soon after. Evol spans the aching dream of infatuation that is ‘Shadow of a Doubt’, the music box chimes of ‘Secret Girl’, the eerie chants of ‘Green Light’ or ‘Marilyn Moore’, even spoken-word poetry over galloping guitar in the form of Lee Ranaldo’s ‘In the Kingdom #19’ interrupted by Thurston Moore tossing firecrackers into the vocal booth.

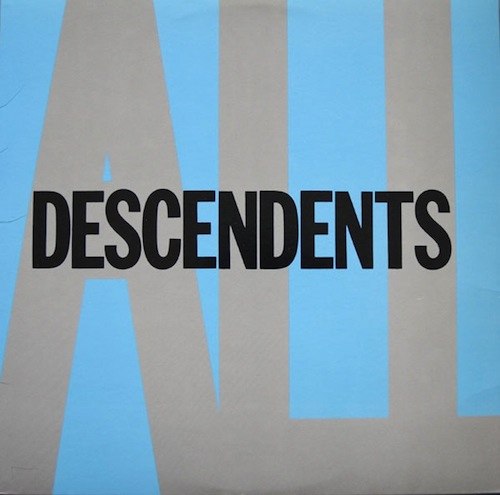

Descendents

All

(1987)

True innovators, Descendents had been in-and-out of the punk scene for a decade by the time Greg Ginn provided an outlet for All. Elements of the nasal vocal delivery will be familiar to listeners of everything from Green Day on through Emo, the voice of the youthful everyman. The guitar sound too had taken hardcore’s fury and replaced it with a certain joie de vie, emphasising the energy, shaving the aggression for a smoother style a million miles away from the earlier scene. There’s even an artful ballad full of twists and turns and semi-acoustic guitar touches.

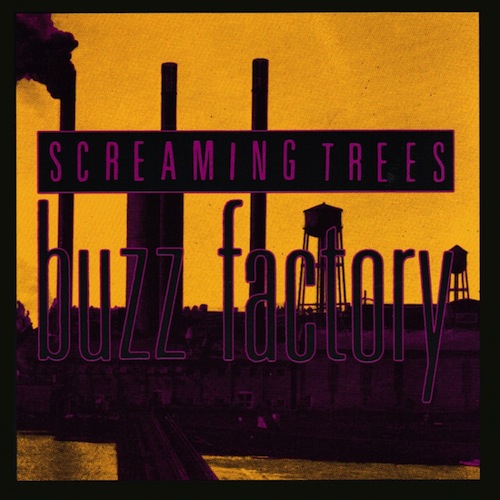

Screaming Trees

Buzz Factory

(1989)

As SST’s ethos spread ever wider it came to embrace most of the musical movements that would succeed it. As well as playing host to Soundgarden, SST had a fruitful relationship with Screaming Trees encompassing three albums and an EP. Buzz Factory is a personal favourite, Mark Lanegan’s trademark growl is mellower, used with a comfortable and easy control – it’s possible to hear him forging the template for Eddie Vedder and the mid-’90s grunge mainstream vocal sound. Meanwhile the band exhibited a superior grip of what ‘good’ grunge was – a twisted rope of punk snarl and noise pirouetting round the soaring brightness of Seventies rock guitar lending the music intensity and enjoyment all at once.