Published on

August 21, 2018

Category

Features

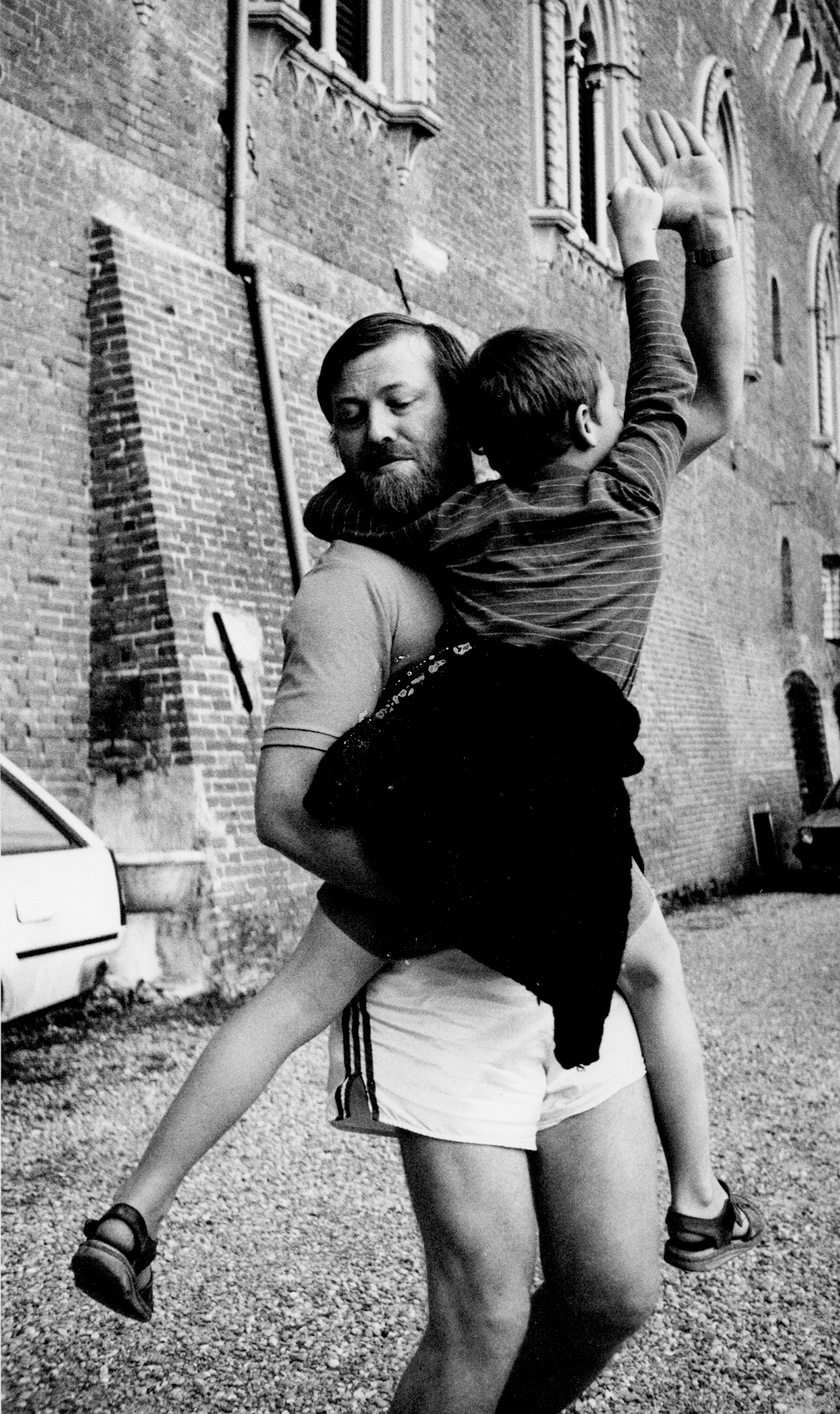

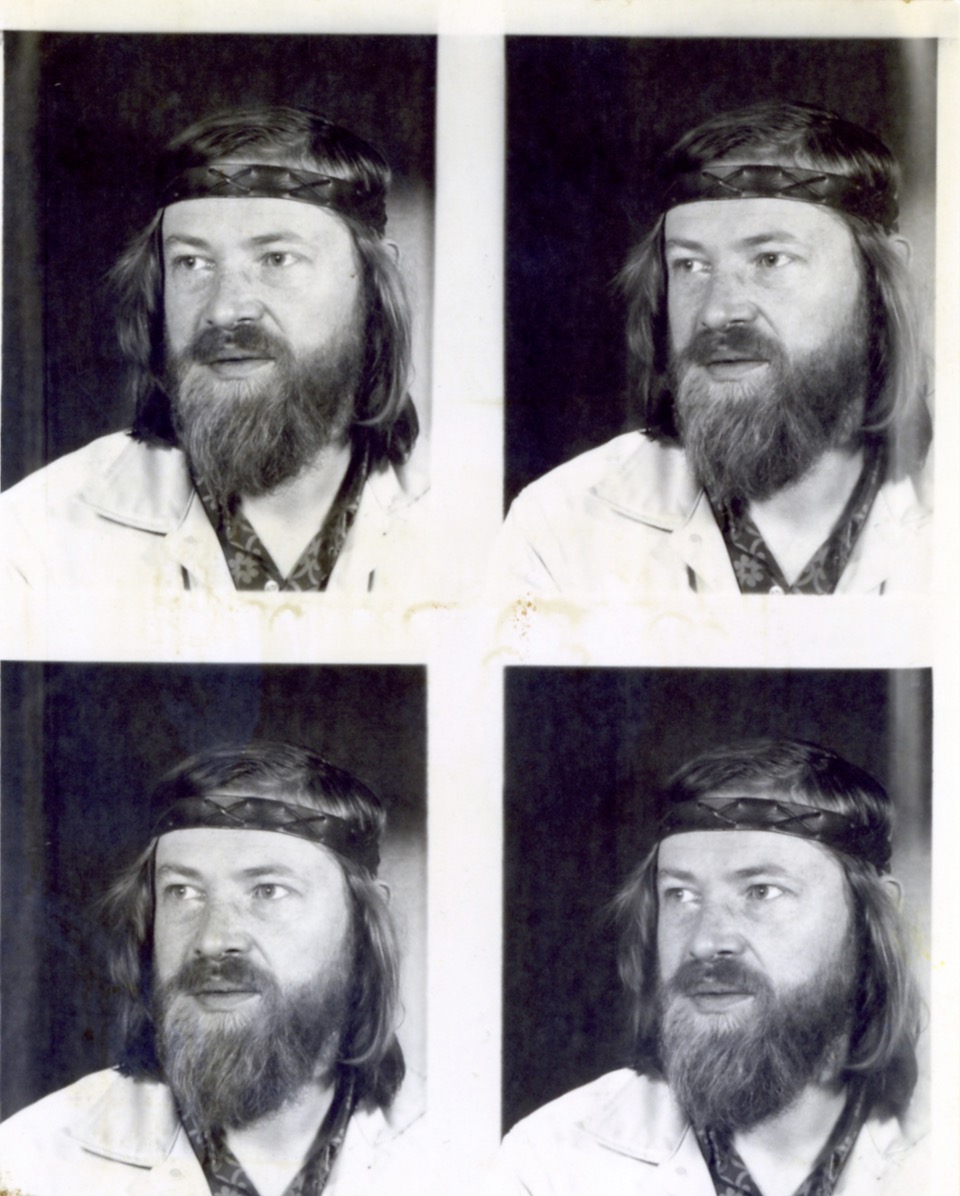

Conny Plank: The Potential of Noise is a documentary that explores the career of the game-changing German electronic music producer by talking to the musicians with whom he worked – from Can’s Holger Czukay and Kraftwerk’s Michael Rother to Whodini’s Jalil Hutchins. Chris May meets Conny Plank’s son, Stephan Plank, the instigator and co-director of the film.

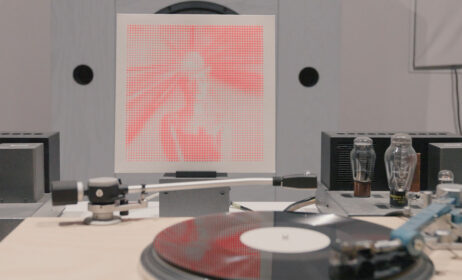

Conny Plank’s career as a producer was short, lasting from 1969 until his death in 1987 aged just 47, but its impact was immense. Among his contemporaries, only ECM’s Manfred Eicher comes anywhere close to matching Plank’s influence, pioneering the concept and use of the studio as instrument in a European context.

As a key participant in the spectrum of styles that were given the umbrella-description krautrock in the 1970s, Plank worked with practically every artist of importance in the genre, and with them influenced emergent ambient, new wave, synth-pop, hip-hop and electronic dance music.

In his film, Stephan Plank interviews the musicians with whom his father collaborated, their recollections and tributes creating a luminous new insight into Plank’s life and work.

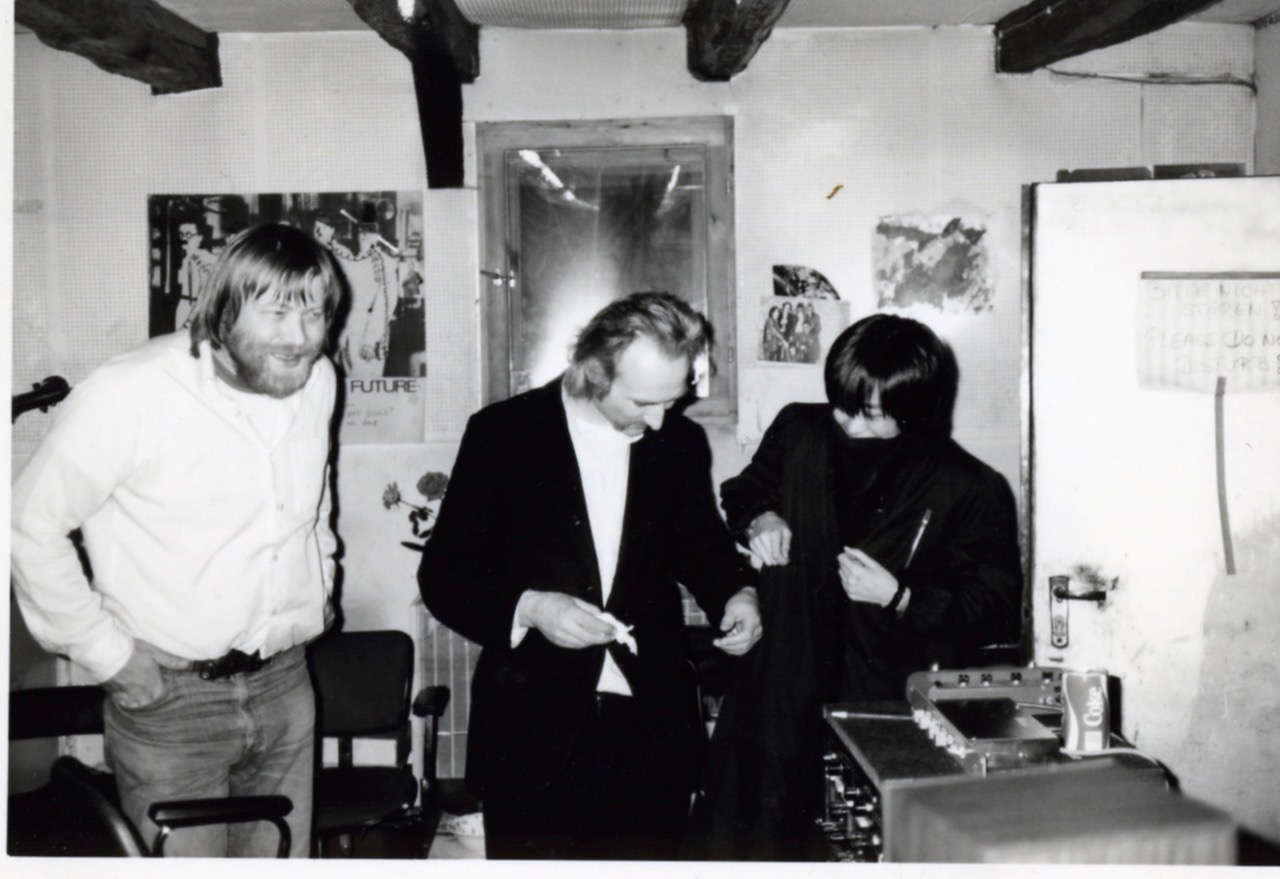

Stephan met all these musicians as a child, while they were recording at Conny’s residential studio and family home in a converted farmhouse outside Cologne. This shared history unlocked many doors and memory banks during the making of the film, whether recording with Duke Ellington or shopping for breakfast cereal with David Bowie.

What prompted you to make The Potential Of Noise?

I was just 13 years old when my father died, and as a child you don’t talk to your father much about his work. So my main reason to do the film was to understand how Conny’s work happened. I thought the best way to learn this was to interview the artists whose music he produced.

One thing that’s abundantly clear in the film is that the people you interview seem to have genuinely loved and respected Conny. The praise they heap on him isn’t standard music-business hyperbole. There is a different dynamic going on. Why do you think that was?

I felt that too. I think there are two reasons. The first is because when Conny started producing bands, he usually took them on at a very early stage in their careers. They were not the great stars they had become by the time I interviewed them, and so Conny was a kind of father figure to them. The other reason was that they remembered me as a child hanging around the studio, having meals, and maybe playing games with them. They embraced Conny as a father figure, and perhaps also looked on me as a sort of younger sibling. In the film, they felt they were telling their stories to someone who was close to Conny, and in a way, close to them too.

Did anyone say no to being interviewed?

One person.

Can you say who that was?

I think you can guess.

[In 1986, Plank famously turned down an approach to produce U2’s The Joshua Tree. After meeting the band, he was quoted as saying, “I don’t think I can work with this singer.”]

As well as Bono, did you also try to speak to David Bowie?

We were in the process of negotiating an appointment to interview him when he unfortunately left the planet. I had met David in 1978. He was involved in the Devo production and came along. He enjoyed going grocery shopping with my mum. I was only a little boy, but I remember going with them. At the time, the supermarkets in Germany had ashtrays in all the aisles, and I remember walking up and down the aisles with David, who was smoking all the time. He was also looking at the breakfast cereals. He was really into cereals, and at that age so was I, so I felt a bond with him. Apparently he enjoyed these shopping trips, because in our little town no-one recognised him and he could just be himself.

Your interview with Whodini is particularly moving.

The Whodini interview was a real gift. When you talk to the German guys, they are very controlled in their language, they are very precise in how they tell their stories. The Whodini guys were a treat because they just opened up their hearts and it all poured out. Jalil explained how when he started the session with Conny he couldn’t get comfortable with the headphones. Conny sensed something was wrong and said “Why are you behaving like this? What’s the problem?” And Jalil said, “Well, I prefer it when I’m performing live and there are speakers behind me and I don’t have headphones and I feel free.” So Conny constructed a PA behind him, and balanced it with the mic, so Jalil could record without wearing headphones. This was very moving for Jalil, because nobody had ever taken time like that for him before. It was always rush, rush, rush in the studio, do what you are told. Conny always gave the musicians all the time they needed, he never let them feel pressured.

The artists Conny produced also spanned an unusually wide range of styles and genres…

His range of interests extended far beyond krautrock. And it was not like he was into krautrock for a few years and then decided to leave it and go elsewhere – he did it all together, all mixed up. All these strands continued alongside each other. He was looking for innovation first and foremost and it didn’t matter in what style of music he found that innovation. And he did not try to impose his own rules on the artists, he just wanted to help them express themselves.

I imagine artists would just come to him with projects.

That was the way it worked. He never went out pitching to artists. I remember sitting at the kitchen table in the morning and Conny would have a big crate of demo tapes. He would take one out at random, listen to it and ask, “Can he sing or does he have to sing?” Just being able to sing was not a criteria that would make Conny think it was interesting. But if somebody had to sing, that was interesting, and he would work with them.

Is it true that Conny worked with Stockhausen in the 1970s and that you are preparing the tapes for release?

There was a collaboration between Conny and a Stockhausen, but it was not Karlheinz Stockhausen, it was one of his sons. He did meet Karlheinz when he was a sound engineer at the radio station in Cologne during the late 1960s, and he met Holger Czukay and the Can guys through him. But that was all.

That’s a shame. A Conny/Karlheinz album would likely be amazing.

Indeed. But one thing that happens when someone like Conny dies is that the stories get embellished. Mind you, I found one that I thought was a tall tale, but it turned out to be true. Conny worked with Duke Ellington in 1970 and Ellington was supposed to have said to him, “Young man, you are doing a good job.” So I searched through the archive and I found a session tape and Ellington had indeed written those words on the box. Ellington was doing a tour of Germany and he needed a rehearsal space in Cologne. Conny arranged for the studio he worked in [Plank did not have his own studio in 1970] to give it to him for free because Conny was a big Ellington fan. Duke did the rehearsal and Conny asked, “Can we do a recording?” And Duke said, “Let’s do one now.” Maybe I’m putting too much onto it, but to me it sounds rather kraut-y. [The session was released in 2015 and it does indeed sound like Plank nudged Ellington out of his comfort zone. Quite an achievement for a young producer working with a veteran genius].

What’s your take on the rumour that Conny recorded a big band session with Marlene Dietrich at the end of the 1960s?

It might have happened, but I haven’t found any corroborating witnesses, or anything to prove it – yet. When I first heard the story I felt it was a myth, but since I found out that the Ellington story was true, I am open minded. I have learnt that when it comes to music and Conny, almost anything might be true.

Conny Plank: The Potential Of Noise will be screened at the DocHouse in London on 27th August, followed by a Q&A with Stephan Plank. Click here for more info.