Published on

March 15, 2019

Category

Features

From Herbie Hancock and Prince, to The Human League and aerobic work-outs.

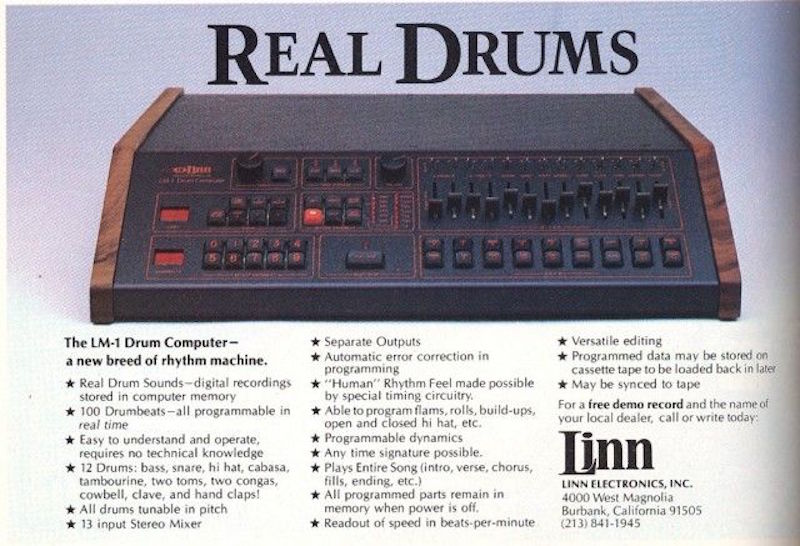

“Real drums at your fingertips”, reads the brochure header for Linn Electronics’ pioneering drum computer, the LM-1. By today’s technological standards the product, which was released at the beginning of the ’80s, doesn’t sound all that groundbreaking. Yet at the time of release, the LM-1 represented a significant step forward for the production of popular music.

Prior to its invention, drum machines like the Roland CR-78 gave users synthesised drum sounds, a bank of preset rhythms and limited programming control. Unusual devices like the Chamberlin Rhythmate had shown promise, playing recordings of acoustic percussion from a selection of tape loops, but no such design had become viable for widespread production.

Linn’s fully-programmable drum computer was leaps and bounds ahead of the competition: containing samples of real acoustic drums that could be tuned, sequenced, mixed, quantised (pulled into alignment with a time grid and then ‘swung’ or ‘shuffled’ to sound less rigid) and individually processed via direct outputs to external hardware.

So how did Roger Linn, a guitarist and electronics enthusiast, do it? Firstly, he had some compelling inspiration. Linn knew and worked with pianist Leon Russell, one-time member of the famous Wrecking Crew studio band. Russell had used rudimentary, fixed-pattern drum machines in the studio since the mid-’70s, recording to the rigid rhythms, so that live drum tracks could be easily added and replaced, where necessary. He and Linn had discussed Russell’s methods, and his approach influenced Linn’s eventual design. So too would the ideas of Toto drummer Steve Pocaro, who reportedly pressed Roger about the digital sampling side of the technology.

On top of that, Linn had an understanding of computer processes, program language and how to optimise available memory.

When he began developing his LM-1 prototype, computer memory was incredibly expensive, but Linn knew he had to find a way to work within the confines of affordable ROM. As he told VF, “one of the innovations that I had in the LM-1 was to say: so far these numbers [digitised audio] have been stored on tape, but if all I need is a drum beat… It would take too much expense/memory to store an entire drum beat as a loop. But I thought, if I can just record and store one recording of a bass drum, one recording of a snare drum, one recording of a hi-hat, in static electronic computer memories, and then store those recordings without ambience, (so you could always add your ambience later) that takes up a very short period of time, maybe an eighth of a second.”

Using a late ’70s Compal 80 computer, for which he had a written a program to sequence drum parts and “spit the signals out to a drum sound generator board obtained as a service part from the Roland company,” he was able to take the first steps toward realising his idea. “I had worked with Leon Russell for a few years before then,” Roger explains, “so I showed him this prototype and he said, ‘can I have one?’” With only the prototype to hand, Linn, set about making a second.

Russell was so enamoured with Roger’s prototype that he used it for every drum track on his 1979 record, Life and Love, which Roger co-produced. From there on out, Linn was able to refine his idea, consulting with artists, and eventually rolling out his revolutionary product.

The expense of the memory and manufacture meant that the first LM-1 models sold for approximately $5,000, pricing out all except the music industry’s highest-earning artists and profit-making studios. The models also had some teething issues, but those were addressed with two revisions of the LM-1, before a cheaper successor, the LinnDrum – not the LM-2, as it is commonly mis-titled – was introduced in 1982.

The LinnDrum was arguably the machine that revolutionised pop music production. Cheaper and more widely produced, it came to market a time when AMS and Eventide were introducing digital reverb units that married wonderfully with its sound – creating the explosive, gated drum sound heard on some of Prince’s finest work, for example.

By the mid-eighties, the ‘Linn drum sound’ was everywhere. From Wally Badarou’s blissful Caribbean electro, to the boogie of South African artists like Sipho Mabuse and Theta, the synth-pop of Libyan artist Ahmed Fakroun and the pop music of Genesis and countless others. However, problems with the Linn 9000, alongside competition from other manufacturers and general business difficulties, saw Linn Electronics fold in 1986.

Roger Linn went on to work with AKAI, realising the next great development in beat technology: the MPC60. Along with the MPC3000, the drum sequencer and digital sampler would become a primary tool in the creation hip-hop instrumentals, and somewhat ironically consign the now out-of-production Linn drum computers to the era of music they had helped define.

That said, the LM-1 still has its committed devotees today, with current owners including the designer and producer Trevor Jackson, as well as techno producers Sterac and Thomas P. Heckmann. Examples of LM-1 usage in newly released music are scarce, especially considering the rarity and expense of the original drum computer.

The sonic similarities between the LM-1 and LinnDrum, combined with regular mix-ups regarding their names, and a tendency to omit the instrument from record sleeves, means the following ten records contain a mixture of both, each one an example of Roger Linn’s groundbreaking design influencing the feel and foundations of the music.

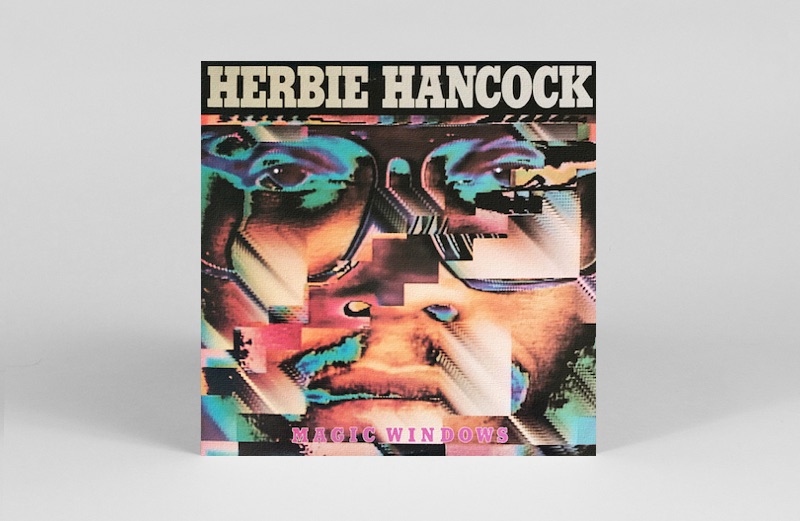

Herbie Hancock

Magic Windows

(Columbia, 1981)

Throughout his career, Herbie Hancock has consistently embraced new music technology. From his experiments with the ARP Odyssey in the early ’70s, to his Fairlight CMI tutorial on Sesame Street and his use of the Roland AX-7 keytar at the turn of the century, he’s been an early adopter of technological change without inundating his records with the new gear he has uncovered.

Hancock used the LM-1 sparingly on his 1980 LP Mr. Hands, but slightly more actively on Magic Windows. It lends a pulsating rhythm to electro-fusion closer ‘The Twilight Clone’, beginning with an unaccompanied hi-hat pattern that demonstrates how digital reverb can give the short, dry samples a grandeur and low-bit shimmer. Use of the LM-1 is credited only on the closing track, but it appears that John Robinson’s snare is doubled with an LM-1 clap on ‘Everybody’s Broke’. Although, thanks to the LM-1’s sampling accuracy, real claps processed with the same reverb unit could also be responsible for that sound.

Patrick Cowley

Megatron Man

(Virgin, 1981)

Considered one of the fathers of electronic dance music, producer Patrick Cowley used the LM-1 to brilliant effect on his 1981 record Megatron Man, programming punchy beats with detailed layering. Known to have been a talented percussionist, Cowley will likely have overdubbed live drums, especially since the LM-1 lacked crash and ride cymbals, which were available as extra on interchangeable EPROM chips. For the sci-fi themed title track, he lays down a rigid 4/4 groove with an almighty snare sound, building a synth-and-vocoder-laden space disco odyssey around it. On ‘Get A Little’ and ‘Thank God For The Music’, the LM-1’s percussion samples come into play as well. An awesome precursor to French touch, the record shows Cowley’s vision as a producer and arranger.

Craig Leon

Nommos

(Takoma, 1981)

Craig Leon’s Nommos represents a bold and experimental use of the LM-1, where snares are processed to a springy digital crunch, hi-hat decays are elongated, and pitched samples are processed to an almost modular synth-like quality. As Leon told VF in 2014, he was “trying for sounds that were not immediately recognisable,” adding, “I think that the rather unconventional way that I used [the LM-1] leant itself to creating the sonic environment of those recordings.” The album was reissued by RVNG Intl. in 2014 as part of the Anthology Of Interplanetary Folk Music Vol. 1.

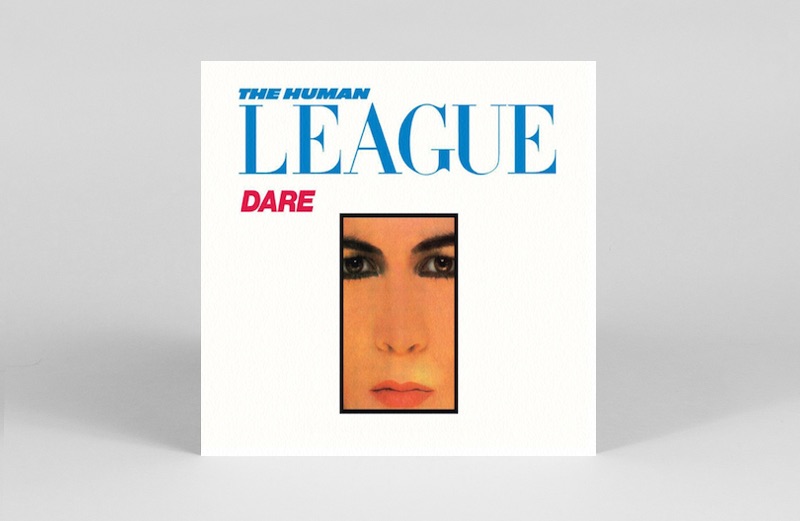

The Human League

Dare

(Virgin, 1981)

In the hands of The Human League, the LM-1 received one of its first major pop endorsements. The band stormed the charts with the LM-1 in tow on Dare’s first single, ‘The Sound of the Crowd’. Released in April 1981, ‘The Sound of the Crowd’ makes expert use of the stereo field, with the LM-1 kick and snare holding down the centre while, percussive elements lurch from left to right. Following its release, the smash hit single ‘Don’t You Want Me’, which was the 1981 Christmas number one in the UK, cemented the sound of the LM-1 into the minds of the British public, alongside Gary Numan’s LP Dance, which also made great use of it. The drum computer was about to become a pop production staple, and The Human League had helped pave the way.

John Carpenter & Alan Howarth

Escape from New York (OST)

(Varèse Sarabande, 1981)

John Carpenter’s score to his own post-apocalyptic sci-fi creation seems an unlikely place for the LM-1 to feature. The darkness, violence and peculiarity of the screenplay was said to have initially deterred studios from producing the film, so you’d be forgiven for expecting a score packed with discordant strings and bass drones, as opposed to sprightly LM-1 beats. Somehow the LM-1 fits in seamlessly, giving a fresh rhythmic edge to the score that reflects the darkness of the plot.

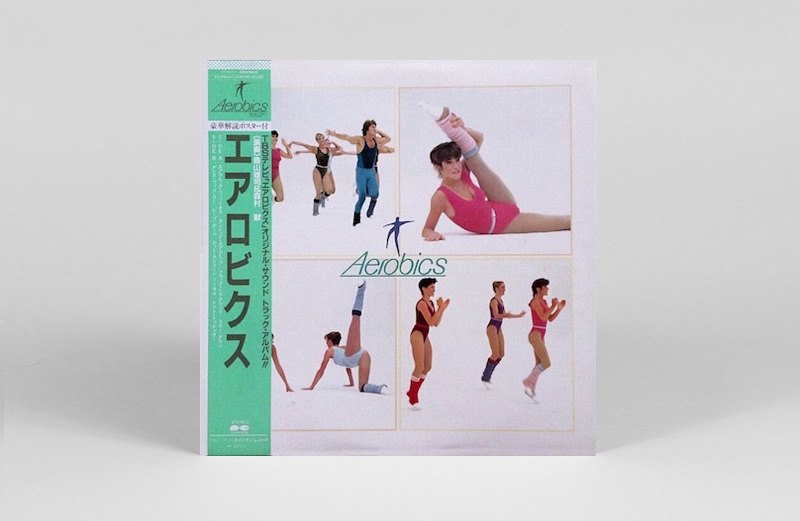

Yuji Toriyama & Ken Morimura

Aerobics

(Canyon, 1982)

As its title suggests, this is a record created for aerobic fitness classes. Its tracks move through a variety of moods: from peppy, pulse-raising 140 BPM synth-pop, to mellow lounge numbers. Toriyama uses the LM-1 beautifully through the record, varying his patterns frequently to keep the class participants moving forward in their workout. Album closer ‘Night Together’ is an unexpected change in groove, but also one of the record’s highlights.

Ultravox

Lament

(Chrysalis, 1984)

Ultravox drummer Warren Cann was an immediate fan of the LM-1. He reviewed it for Electronics & Music Maker magazine in September 1981, stating in conclusion that: “The Linn is so far ahead of anything its field at the moment, that it’s just not worth drawing comparisons.” Cann used the LM-1 expertly on ‘I Never Wanted to Begin’, the B-side to 1981 single ‘The Thin Wall’, recorded at Conny Plank’s Cologne studio. He also incorporated it into what his bandmates called ‘The Iron Lung’: a vast selection of hardware that also included a LinnDrum, suggesting that both were used on records such as Quartet and Lament. There’s a nice variety of Linn patterns on the latter, with ‘White China’ capturing a rougher timbre with clever panned toms, while ‘When the Time Comes’ provides a more fragmented beat with a rhythmic delay.

Prince

The Black Album

(Warner Bros., 1987)

You can’t talk about the LM-1 without heaping praise on Prince’s extraordinary catalogue of work. From 1999 through to Sign ‘O’ The Times and the mysterious Black Album, he returned time and again to the LM-1 that he had purchased at first opportunity, and never updated. He and engineer Susan Rogers treated it with non-linear reverb from the AMS unit, giving each snare, clap and kick a firecracker quality.

In addition to using it on his solo records, he also incorporated the LM-1 into productions for The Time, such as ‘777–9311’ and Vanity 6’s ‘Nasty Gal’, giving those songs the same electro-funk swagger that his singles possessed.

A number of Prince’s records could’ve been chosen for this list, but his once commercially withdrawn, dark and twisted funk gem The Black Album is the one we’ve gone for. Packed with daring character portrayal, and funk grooves that justify its informal title as ‘Funk Bible’, it represents one of Prince’s most creative and ambitious production projects. On ‘Bob George’, he coaxes a purring, modulating tone out of the LM-1 kick, while on ‘superfunkycalifragisexy’, he effortlessly adapts the groove with sleek hi-hat triplets and changes in the kick drum pattern.

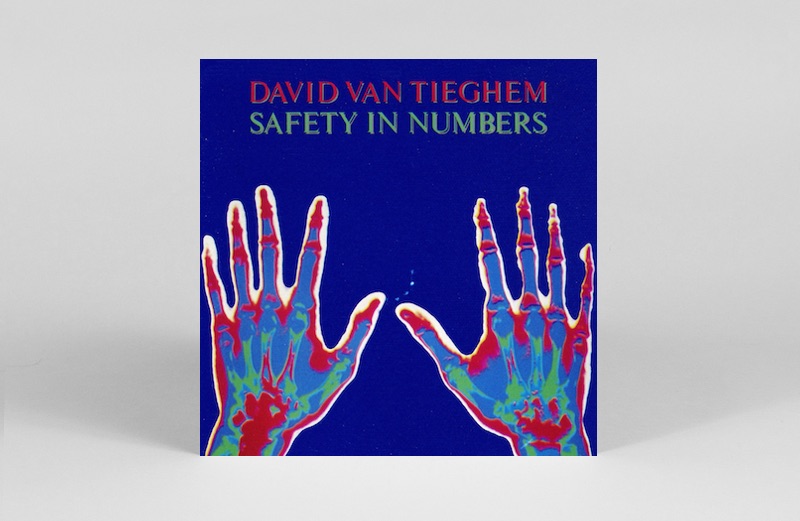

David Van Tieghem

Safety In Numbers

(Private Music, 1987)

David Van Tieghem worked with Ryuichi Sakamoto of Yellow Magic Orchestra on this disorienting and wildly creative record. Utilising roughly 15 pieces of hardware, including synths, sequencers and radios, the LM-1 adds bite and stability to tracks like ‘Night of the Cold Noses’, where textures and ideas collide to form a genre-defying mix of electronic and acoustic elements. It can take a few listens to get onto Van Tieghem’s wavelength, but when you do, his rich arrangements begin to take on previously unrecognised qualities.

The Mystic Jungle Tribe

Plenilunio

(Periodica, 2017)

A handful of contemporary, Naples-based artists, associated with the West Hill studio and booking agency, have made use of the the LM-1 in recent years. They include Nu Guinea, who credit its use on their album The Tony Allen Experiments, The Normalmen, who appear to use it on their track ‘Far Away Horizons’, and instrumental trio The Mystic Jungle Tribe, who lace it through their epic, synth-laden LP Plenilunio. With resonant synth arpeggios, keyboards, electric bass and flutes present, the LM-1 locks into a focussed, throwback groove, giving the record a punchier and less house-y vibe than some of their other work. The LM-1 sounds more playful than their use of the TR-606 and 707 on other records, allowing the trio to alternate between the dance floor and sultry, psychedelic regions, as they do on ‘Forest of Mysteries’.