Published on

August 16, 2016

Category

Features

Luaka Bop boss Yale Evelev shares the purity, joy, casualness and immediacy of African music recorded in the field.

Words: Yale Evelev

In the 1970s I got into recordings made in the field for many of the same reasons punk started. I was looking for something purer and more honest than a lot of music felt at the time; music made without commercial reason, to appeal to no radio segment or demographic group.

I know field recordings seem pretty esoteric, and to some extent I guess they are. Record labels and ethnologists started recording ethnic communities in the 1920s and ’30s. Record labels started doing this because they realized, in a more atomized world, there were communities – who they had not been serving – that would buy records. Ethnomusicologists felt they were documenting disappearing cultures and, with the dawn of equipment they could take in the field, had a means to record, and not only transpose, music made in these settings.

Some of these recordings precipitated the beginning of the musical avant-garde both in Europe and the U.S. Henry Cowell, hearing recordings of Indonesian Gamelan and African musics, incorporated those tonal and rhythmic ideas into his own compositions as well as lecturing about these musics in his classes at New York’s New School. (His students included John Cage, George Gershwin, Lou Harrison, Burt Bachrach(!) and many others in the early U.S. avant-garde community.) As well, Cowell’s interest in non-Western rhythms encouraged him to invent the world’s first drum machine with Léon Theremin in 1930, the Rhythmicon.

In the 1950s the French started releasing musical cultures from anywhere they had a colony. These started to come out as 7″ singles and on 10″s on Ocora, a label owned by Radio France and started by the electronic pioneer Pierre Schaeffer.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization also had an ethnographic recording project curated by Frenchman Alain Danielou (who also wrote a book on the penis and translated the Kama Sutra). They did very extensive recording and documentation of different communities. Eventually these recordings would come out sponsored by UNESCO on Philips, Barenreiter and many, many other labels.

Listen to some of the records in this playlist:

By the time the 1960s came along, interest in American regional folk musics, hippy trail travels, high quality portable Nagra recorders, and counter culture ethos combined in the States. The result, as far as we are concerned here, is that people who weren’t necessarily ethnomusicologists like David Lewiston and Englishman John Storm Roberts, did field recordings of mind blowing music from Indonesia, the Caribbean, Africa and South America and released them on labels like Folkways and Nonesuch. These were the ones most readily available in the States and became a bellwether for folks who wanted to expand their ideas about what kind of music existed in the world. (David Byrne tells about listening to records from the Nonesuch Explorer Series in his local Baltimore library when he was in high school.)

After being mostly exposed to those Nonesuch and Folkways albums it was a revelation for me to come across the Ocora label. Though many of the Nonesuch records were very listenable and not just hardcore ethnographic examples, the Ocora label was on another level of recording quality and musicality. I got the impression that Teresa Stern of Nonesuch and Moe Asch of Folkways would often allow friends with Nagras and a plane ticket to release stuff. We were most assuredly better off for it as this resulted in some wonderful albums. But in terms of consistency, I don’t believe much beats the quality of the Ocora catalog.

The selection below is an assortment of African recordings made in the field. What sets apart these albums perhaps from others is that there is an attempt to make an album of music that works as something one would listen to. I know that hundreds of hours of recordings were sorted through to create these albums and in that way we realize that everything is a mediated version of something.

Ba-Benzélé Pygmies

The Music Of The Ba-Benzélé Pygmies

(Bärenreiter-Musicaphon, UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music, 1996)

There are a lot of recording of Pygmies, most of them are good and some are great. This is a great one. Everything I love about music recorded in the field – the purity, the joy, the casualness and immediacy – is here in the music the Pygmies make. This is the pinnacle of music making and for me, the pinnacle of musical enjoyment.

Gbáyá

Empire Centrafricain – Musique Gbáyá / Chants À Penser

(Ocora, 1977)

This is a recording made of two guys playing sanzas (thumb pianos) in the evening outside the place they are serving as security guards for. There are no professional musicians in Gbaya society. All Gbaya people participate in communal singing and dancing and play various instruments from when a young age.

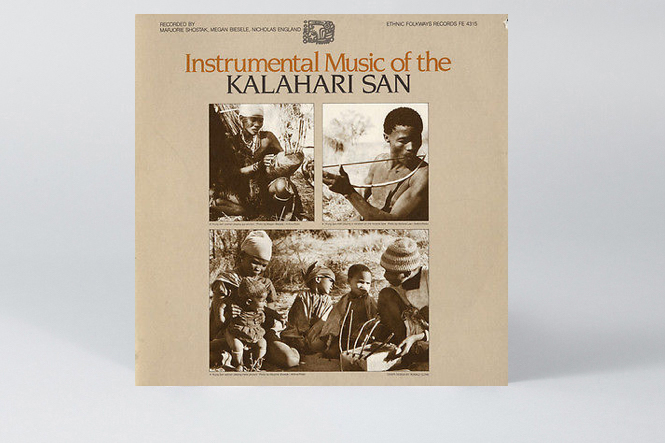

Various

Instrumental Music Of The Kalahari San

(Folkways Records, 1982)

These are recordings of another hunter gatherer society, similar to the Pygmies. The album was recorded by Majorie Shostak, who is part of a long line of untrained ethnomusicologists – like Colin Turnbull in the ’40s and ’50s and Louis Sarno today, who have both done important work with the Pygmies born out of a passion for their music. Music for the Kalahari is both a community building exercise and a source of entertainment. That could of course be said for other societies and ours as well, though for Kalahari, without TV, movies and iPhones it probably takes on a much greater meaning. Though they live in a desert area, their music is very liquid-y sounding. As a side note, Marjorie was an early proponent of the Paleo diet.

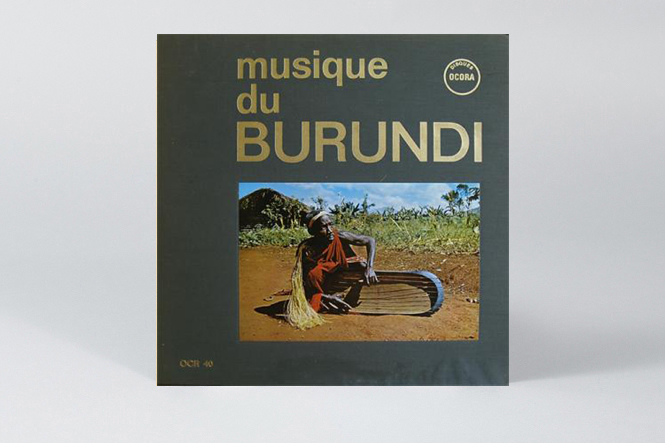

Various

Musique Du Burundi

(Ocora, 1968)

A lot of ethnographic recordings have been influential; I mentioned Henry Cowell, but of course I could also mention the work of Steve Reich, Philip Glass, Ennio Morricone, and so on. In the ’80s, Malcolm McLaren started a craze in the UK called the ‘Burundi Beat’ with Bow Wow Wow and Adam Ant (both managed by McLaren). The inenga (trough zither) recordings on this album also influenced jazz trumpeter Don Cherry’s Brown Rice album on Horizon Records.

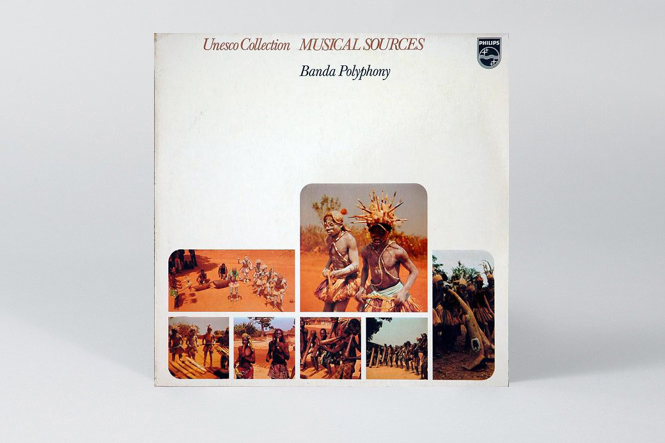

Linda / Dakpa

Banda Polyphony

(Philips, UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music, 1976)

The orchestration of Banda music compiles polyphonic layers of wind instruments made from tree roots, bamboo, and antelope horns. Their ensembles are composed of a variety of flutes, horns, whistles, drums, and voices playing independent melodies that weave together in hocket. The ensembles are usually accompanied by jingles that are struck together or worn by dancers. Each horn plays two notes and the tones interlock, like singing rounds. Great.

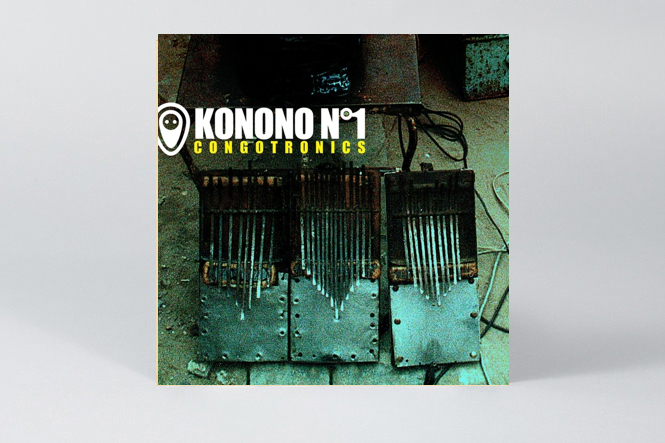

Konono Nº1

Congotronics

(Ache, 2005)

The Pygmies, the drummers of Burundi, the Banda trumpeters, who knows how long those musics have been made that way? Konono, on the other hand, is making 21st Century music. The fact is, when the early musicologists were rushing around documenting a disappearing world, the world was rushing around reinventing itself in new permutations. This music originally heard on the streets of Kinshasa has indeed been produced on these albums, but enough of the original feeling remains and there is enough filmic representation that it belongs here.

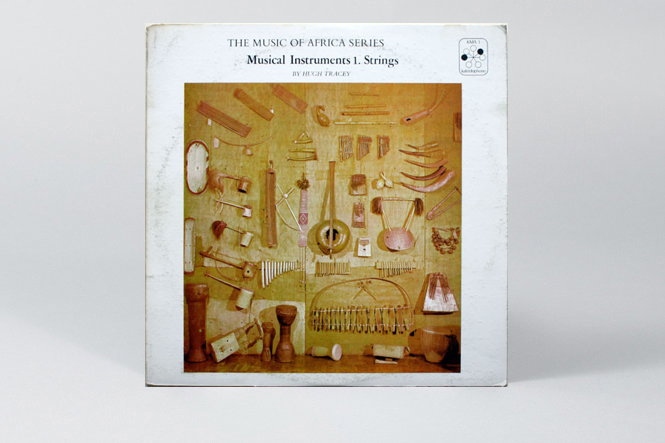

Various, Recorded by Hugh Tracey

The Music Of Africa Series – Musical Instruments 1. Strings

(Kaleidophone, 1972)

Hugh Tracey was a controversial figure who recorded throughout East and Southern Africa and released possibly 100 records. And though some of his recording techniques were frowned upon by ethnomusicologists and his later poor treatment of workers who manufactured Kalimbas for his sale and distribution made him few friends, he did document a lot of music. The records as whole albums are not always as great as they could be, but there are some standouts. I particularly like the acoustic guitar music of William Osale, and, perhaps one of the most famous ethnographic tracks of the moment, ‘Chemirocha’. The track was recorded by Tracey among the Kipsigis people of Kenya in a place called Sotik, where they had gotten a hold of some 78s by Jimmie Rodgers, an early country and western star known as the yodeling brakeman. The Kipsigis did not believe such sounds could come from a human so they attributed his singing to half man half antelope and named this piece of music after him; Chemi (Jimmy) Rocha (Rodgers).

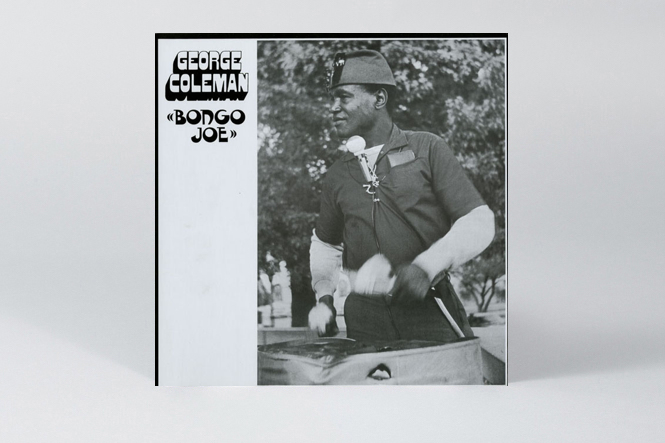

George Coleman

Bongo Joe

(Arhoolie, 1969)

This might be considered stretch to fit in this list by some. It’s Afro-American instead of African for one. Chris Strachwitz recorded George Coleman on the streets of San Antonio, Texas in 1968. George would show up in the evening near San Antonio’s River Walk, towing his 55 gallon oil drum behind his moped and play for whomever happened by ’til late. In the 1990s when I went down to record him, (never got a round to releasing this), he told me that he couldn’t leave Texas because he killed a couple of people. The first one was when he used to play in front of the Alamo, someone grabbed his sticks and, George being a big guy, threw him down on the ground where he hit his head and died. The second person he caught coming over his yard wall late one night, and this being Texas, George, sitting on his back porch with a shotgun, shot him. This also being Texas, George served no time but had to stay in state. As the story goes George wanted to be a drummer but couldn’t afford a drum kit. He made his own, a unique set up from a disused oil drum that was lying around this oil producing area. This isn’t any Caribbean style steel band music by the way, but odd improvised pop songs recorded on the street. It is unlike anything else in America and it does fit musicologically on this list – if someone told you it was from an English-speaking African country you wouldn’t have reason to doubt it.

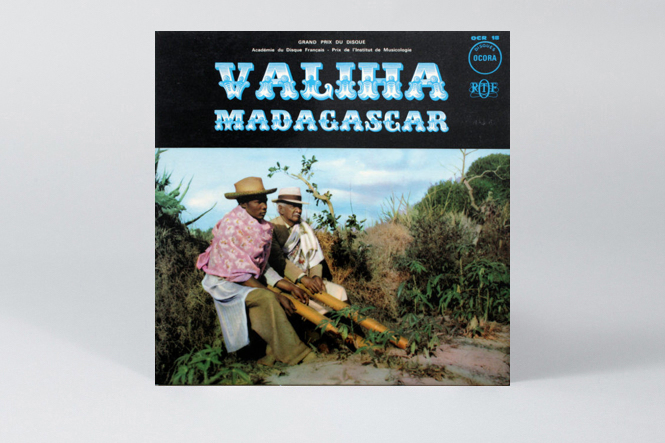

Various

Valiha Madagascar

(Ocora, 1963)

Another classic Ocora album. The valiha is one of the oldest instruments of Madagascar and likely a descendent of similar tube zithers brought to the island from parts of Southeast Asia during ancient migrations. Originally used solely in ritual settings, it is today heard in casual contexts as well, including in popular music. This music was originally associated with the Malagasy aristocracy. Long ago only men played this instrument, but this prohibition is no longer followed, even ritually.

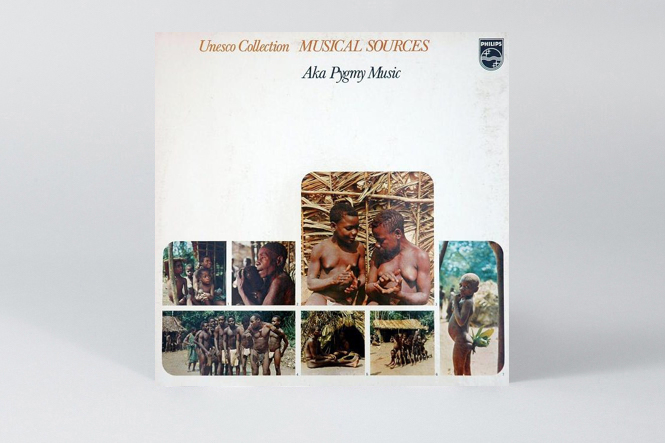

Aka

Aka Pygmy Music

(Philips, Unesco Collection of Traditional Music, 1973)

Here is another great Pygmy album because one really isn’t enough. In particular there is an amazing track of Pygmies hunting and making vocal sounds to chase animals into their waiting nets. We borrowed a neighbor’s cat once to deal with some mice issues we were having. My wife was listening to me play this track on the radio, and it made the cat totally freak out. So it’s not just the forest animals that are affected.