Published on

August 23, 2022

Category

Features

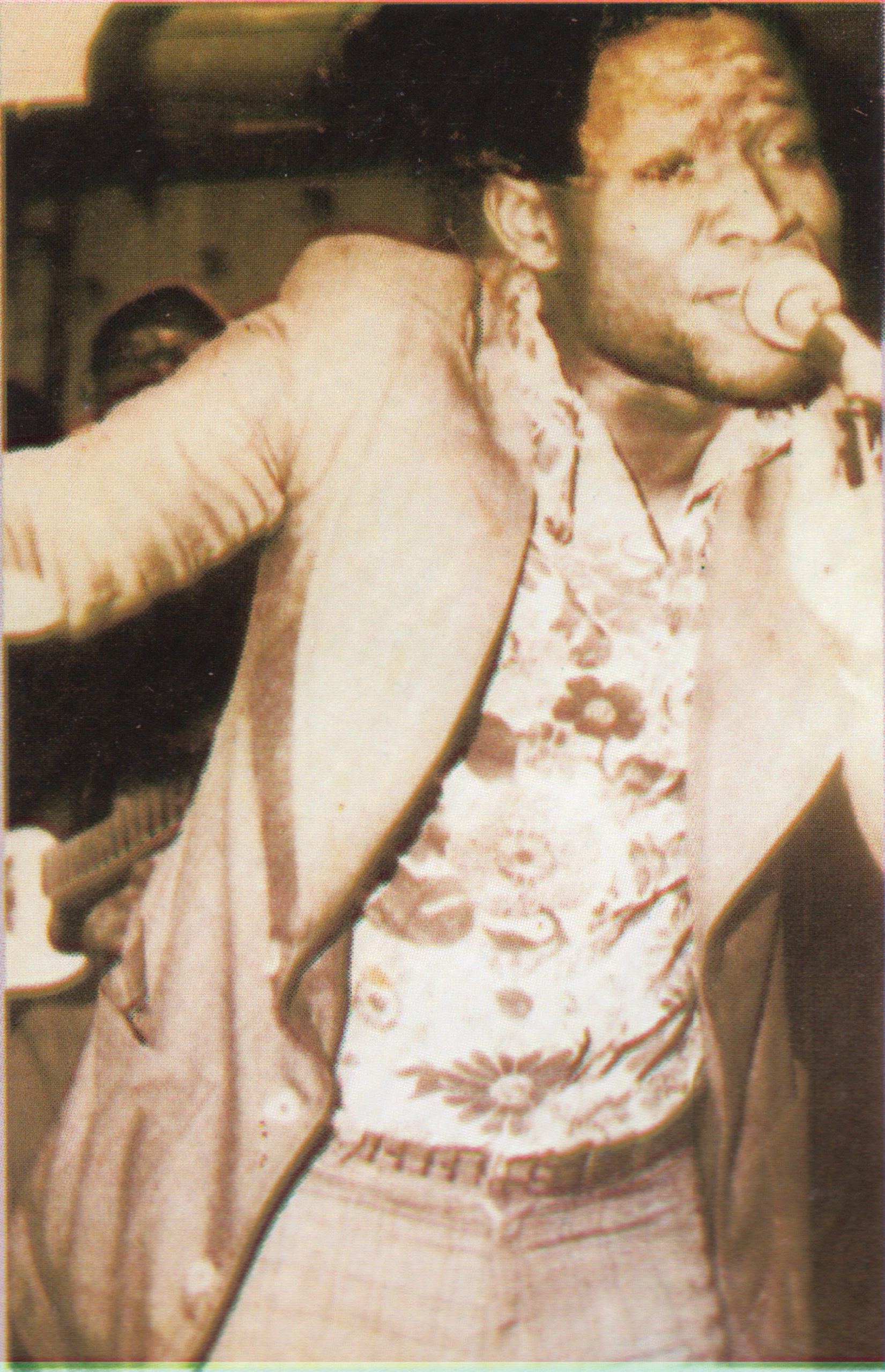

Alhaji Waziri Oshomah’s unique take on highlife combines folk songs with Western pop, and the teachings of Islam — and it’s been forged in equal parts by civil war and the dancefloor.

In 1957, at only 10-years-old, Waziri Oshomah was sneaking out of his home in the southern Nigerian region of Etsako to watch club bands play the highlife music that was taking his country by storm. With their blend of palm wine guitar, Afro-Cuban rhythms, and American swing sensibilities, local groups would recreate hit records by the likes of Victor Uwaifo and Bobby Benson to produce a sound that was unlike any other Waziri had heard before.

“People were moving and they were singing in all different kinds of dialects,” the 76-year-old says over the phone from his home in Edo state now. “It excited me and made me want to join in also.” Before long, school-age Oshomah’s conspicuous presence in the clubs led to Etsako groups like Yakubu “Anco” Momodu & His Afenmai Dance Band inviting him onstage to sing a few numbers alongside their groove-heavy backing.

All of this was unwelcome news for Oshomah’s devoutly Muslim parents. Worried that music would turn their child towards a life of drinking and sin, they threatened to disown him if he continued.

Oshomah remained undeterred. He quietly kept writing and making music while attending school — all amidst the backdrop of religious tensions during the Nigerian Civil War of the late 1960s. With his parents’ entreaties ringing in his ears, from the mid-70s onwards Oshomah forged a fusion style that incorporated highlife with Western synthpop influences and moralistic lyrics that expounded on the teachings of Islam.

It proved to be a uniquely potent blend — one that united Muslims and Christians on the dancefloor, and which led Oshomah to ditch his day job to perform full-time and ultimately become a key musical name in Edo state and beyond. “I came from such a remote area that I was very surprised people accepted what I was trying to do with the music,” he says. “My songs are not just Islamic — they teach morality for everyone and encourage us all to live a good life.”

His lyrical choices also led Oshomah’s parents to finally approve of his music. “They understood eventually,” he laughs. “They could see I hadn’t changed as a person — I was still devout, and my songs encouraged people to be good to each other. Even if you don’t understand my language, you will dance to my beat, since this is music for all humans.”

A compilation of Oshomah’s formative fusion tracks recorded from the mid-70s to the mid-80s is now being released as the third instalment of Luaka Bop’s World Spirituality Classics series, following editions from Alice Coltrane and a US gospel selection. Yet, Oshomah’s music was an accidental discovery for label manager Eric Welles-Nyström.

“I was travelling to Nigeria lots to visit William Onyeabor in the 2010s and on these trips I would buy records from a collector in Lagos who had so much inventory he would sleep on it in his shack,” Welles-Nyström laughs. “The records would be so dirty that the first Waziri album I bought was actually inside the cover of another LP. When we played it in the office, it took us by complete surprise but we immediately knew it had a special power, since it sounded like nothing else.”

Welles-Nyström set about finding Oshomah in 2018. Within a year, he was on a flight back to Nigeria to sign a deal with the artist.

“The World Spirituality Classics series had come about in 2016 partly to inspire joy amidst the political and social chaos that was happening around the world at that time,” he says. “Waziri felt like a perfect fit for the series, since these aren’t albums that expound on a specific religion — they are about uniting people and Waziri does exactly that via the dancefloor.”

Inspiring musical communion was an effect Oshomah naturally came upon while he was forming his sound in the wake of the Civil War.

“We were so limited back then to the areas we could play and the infrastructure was terrible, so we had to walk miles to our gigs, often playing without electricity or amplification,” he says. “But our audience would be there. That experience taught me just how powerful music was in bringing people together, even in the most trying times. The songs were a perfect vehicle to convey a message.”

Across the seven tracks of Oshomah’s World Spirituality Classics album, that message can be a call for people to work together (on the mid-tempo funk of ‘Ohmona-Ohmona’), celebrating the power of self-belief (over the shuffling rhythms of ‘Okhume Ukhaduame’), or, simply, one of love — which steers the closing duet My Luck, written by and featuring Oshomah’s wife Hassanah. “She is the sweetness to what I am saying,” he says. “Her voice unites the melodies.”

With five decades of performance and hundreds of recordings under his belt, Oshomah says the thought of retirement occasionally enters his mind. “I want to stop and rest but the younger generations are still discovering me,” he laughs. “I have only ever tried to do my best and it’s nice to see those efforts now being appreciated around the world.” So putting his feet up may be a while off yet: an international tour awaits first.

There are detractors, of course — those clerics who view performance in any guise as against the teachings of Islam — but Oshomah has constantly faced opposition in his life. It is merely fuel to his fire. “In life, there are always those who want to take away from what you’re doing,” he says. “But I only have to look at the people enjoying my music to know that I have a legacy that will last.”

Photos courtesy of Eric Welles-Nyström, Alhaji Waziri Oshomah, and Luaka Bop.