Published on

October 31, 2014

Category

Features

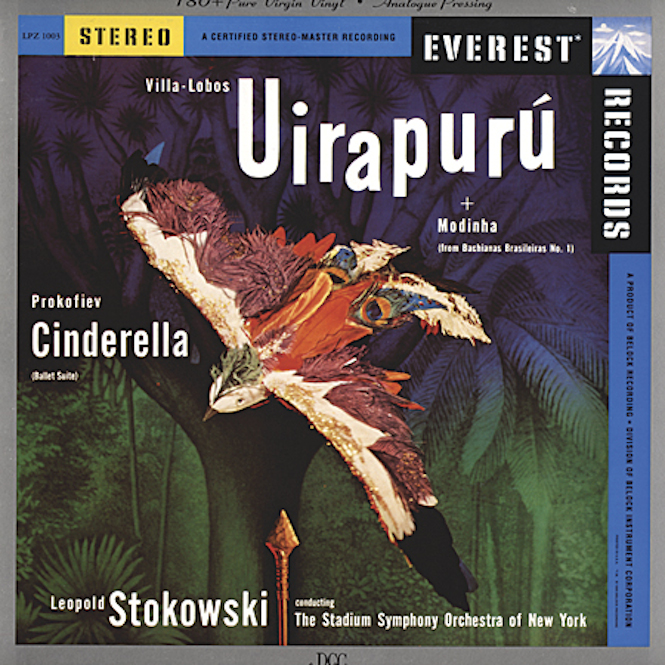

Today the biggest hurdles in record album design are the marketing people and those artists with final approval rights. Back then marketing experts were benign and even the most temperamental recording artists offered much less trouble, at least in relation to Steinweiss. The field was too new, and no one had time to figure out what, if any, restrictions or taboos should be. Success was its own reward. And many jazz greats and classical maestros enthusiastically applauded Steinweiss’ success at increasing their sales. Leopold Stokowski, for one, wouldn’t have anyone else do his covers.

Cover for Leopold Stokowski’s Uirapuru

World War II interupted Columbia’s steady release of records, and Steinweiss took a civilian job with the Navy. After the war, Steinweiss was put on retainer as a consultant to the President of Columbia Records, Ted Wallerstein.

During one of their routine lunch meetings, Wallerstein was acting mysterious. He walked over to his desk and took a record out of his drawer, put it on the turntable and as Steinweiss listend he also instinctively waited for the record to end. With 78s one got into the habit of waiting for the record to change every four or five minutes, but this one didn’t change. The one side played for twenty minutes and Wallerstein announced that it was the first pressing of an LP record’ [Developed by Dr. Goldmark for the famed CBS Labs]. He then looked Steinweiss and said, “we’ve got a packaging problem.” The package makers tried using Kraft paper envelopes but owing to the heaviness of the folded paper marks were left on the microgroove when they were stacked up. Wallerstein concluded that they had to solve this “or we’re up the creek,”

Steinweiss developed the folded prototype for a cardboard container or jacket that could hold the LP (the inside sleeve was invented by someone else). That was the easy part. Next he had to find a manufacturer willing to invest around a $250,000 in new equipment to print, fold, and glue the thing. He enlisted his brother-in-law to locate a manufacturer. The LP package was a thin board covered with printed paper – four color printing on the cover and black-and-white on the liner side – became the standard for the industry.

Although Steinweiss owned the original patent, his contract with Columbia stipulated the he had to waive all rights to any inventions made while in their employment. The rest is history.

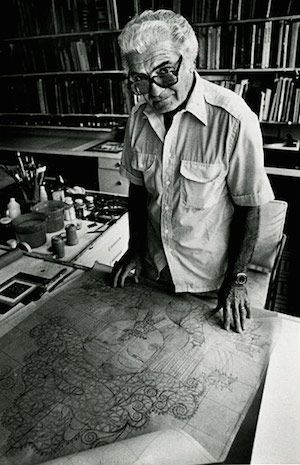

Steinweiss’ invention was not merely effective protection for LPs, it allowed more artistic variety, which for its inventor was a mixed blessing. More advanced printing encouraged the use of photographs, which eclipsed the kind of graphics that Steinweiss had introduced. Studio photography became vogue; dramatic mood portraits and clever setups were popular. Steinweiss preferred the illustrative and typographic approaches but he also art directed and designed photographic shoots for London and Decca records. Indeed he worked for many of the major labels during that period, and sometimes used a pseudonym (Piedra Blanca). Nevertheless, by the late 1950s the pop labels wanted photographs exclusively.