Published on

January 28, 2014

Category

Features

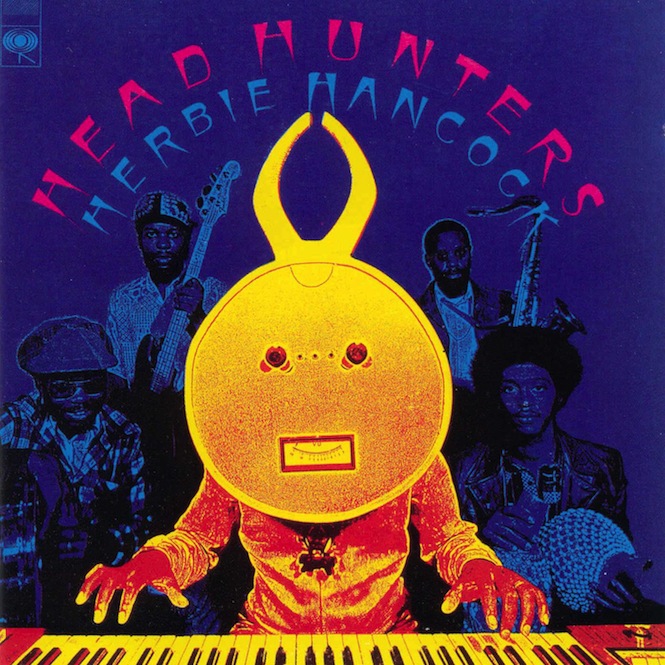

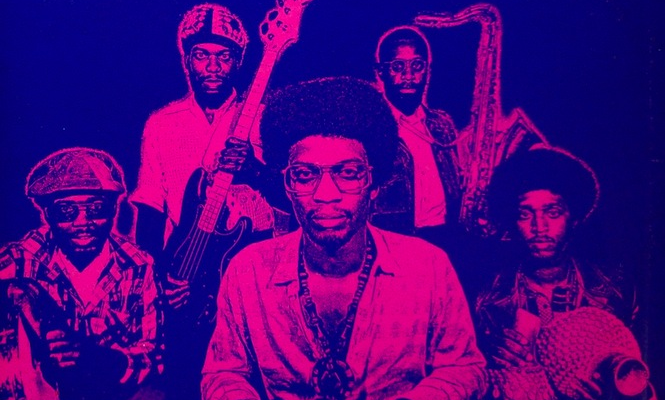

Continuing our occasional feature series, which last time saw us take apart A Tribe Called Quest’s Midnight Marauders, The Vinyl Factory teams up with Classic Album Sundays to explore the roots and branches of the shape-shifting jazz-funk epitome that is Herbie Hancock’s 1973 album Head Hunters.

Channelling the wisdom of the old-school record shop refrain “if you liked that you’ll almost certainly like this”, Roots & Branches picks a different title every month and puts it into the context of ten records it has either influenced or been influenced by, opening your ears to music you might not have heard before. From Miles Davis to Curtis Mayfield, we continue the series with Herbie Hancock and the ten records essential to understanding where Head Hunters fits in.

Words: Colleen Murphy

“My intention was to make a funk record, but the jazz influence kept pulling it.” – Herbie Hancock speaking about ‘Head Hunters’ to The New York Times

Takin’ Off with Miles

Herbie Hancock is one of the most successfully versatile musicians and composers from the past half-century, having made an indelible mark in jazz, pop, hip hop, dance and movie scores. And it seems he has always been something of a musical chameleon as he first studied classical music as a child prodigy who performed a Mozart concerto with the Chicago Symphony at the age of eleven. He was then discovered by the late trumpeter Donald Byrd, appeared on several of Byrd’s albums and then made his debut on Blue Note Records in 1962 with the album Takin’ Off. This album spawned his first crossover hit, ‘Watermelon Man’, which reached the Billboard Top 100 on the pop charts.

His talent and post-bop piano innovations did not go unnoticed and the following year, Miles Davis enlisted him into his second great quintet. Davis wrote in his autobiography, “Herbie was the step after Bud Powell and Thelonius Monk, and I haven’t heard anybody yet who has come after him.” With that kind of accolade, many musicians would think, “It doesn’t get much better than this”, but Hancock simultaneously pursued his own solo career, composing and performing classic albums such as Empyrean Isles and Maiden Voyage and scored Michelangelo Antonioni’s cult film Blowup.

Mwandishi

In the early seventies, Hancock continued his musical journey in the wake of his work on Miles Davis’ In a Silent Way and was inspired by Miles’ follow-up, Bitches Brew. He released a trio of records coined the ‘Mwandishi’ albums that were characterised by their spacey and experimental sonic excursions; an avant-garde jazz-fusion whose impressionist soundscapes were rhythmically rooted. On Sextant, the final release of this triumvirate, Hancock further pushed the boundaries into the future by being one of the first jazz keyboardists to use the latest synthesizers such as the ARP and Moog alongside a host of other keyboards including the Fender Rhodes, Clavinet and the Mellotron, an instrument that had been recently popularised by The Beatles and The Moody Blues.

In many ways, Sextant sits happily aside some of Krautrock’s finest offerings from the likes of Can and Kraftwerk. However, there was a bit of a backlash, as many jazz purists did not like their music “tainted” by studio electronics. On the flip side, we believe Hancock’s sense of musical adventure reflects jazz’s innate sense of freedom. As Hancock told The New York Times, “The thing that keeps jazz alive, even if it’s under the radar, is that it is so free and so open to not only lend its influence to other genres, but to borrow and be influenced by other genres. That’s the way it breathes.”

Funkin’ It Up

“I began to feel that I had been spending so much time exploring the upper atmosphere of music and the more ethereal kind of far-out spacey stuff. Now there was this need to take some more of the earth and to feel a little more tethered; a connection to the earth…. I was beginning to feel that we (the sextet) were playing this heavy kind of music, and I was tired of everything being heavy. I wanted to play something lighter.” (Hancock’s sleeve notes: 1997 CD reissue)

It was time for Hancock to come back to earth and to musically cross-pollinate as he did in the early sixties with compositions such as ‘Watermelon Man’ and ‘Cantaloupe Island’. The funk of Sly and the Family Stone, Curtis Mayfield and The Godfather of Soul were an inspirational stimulus and his mate Donald Byrd was working with the Mizell Brothers who were changing the face of jazz in 1973 with their funk inflected rhythms fuelled by their drummer of choice, Harvey Mason. Hancock enlisted Mason, bassist Paul Jackson and percussionist Bill Summers as his new rhythm section but kept reed player Bennie Maupin from his former line-up to record the new album.

The resulting Head Hunters funk-ed things up with its grooving interplay between the Clavinet and rhythm section. The album still retained its jazz cred with the long improvisations and its recognition that jazz’s roots of swing and syncopation have often been an invitation to the dance floor.

One for the Heads

The album appealed to jazz, R&B, funk and rock fans and to this day is one the best-selling jazz recordings and the first to go platinum. Although it has commercial appeal, Head Hunters is still ‘heady’. Apparently we are not the only ones who believe this to be the case as the album features on Rolling Stone’s ’40 Greatest Stoner Albums’. While listening to the music one could stare at the psychedelic artwork by artist Victor Moscoso who also worked with Zap Comix and The Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia.

Years later, Head Hunters is still of cultural importance. In 2007 it was added to the Library of Congress’s National Recording Registry. Just as significantly, the album has been a major influence on modern music as it has been sampled in hip hop by 2Pac, Nas, Digable Planets and in pop music by Beck and George Michael. Rather than being sniffy, Hancock is delighted that his music is able to cross boundaries. In his words: “The idea of being judgmental to me is not something I aspire to. The beauty of jazz is that, at its best, it’s non-judgmental.”

To hear the music that was relevant, inspirational or contemporary to Herbie Hancock, listen to our Head Hunters Musical Lead-Up above and scroll down to explore the individual tracks and their albums in greater detail.

Herbie Hancock

“Watermelon Man” from Takin’ Off

(Blue Note, 1962)

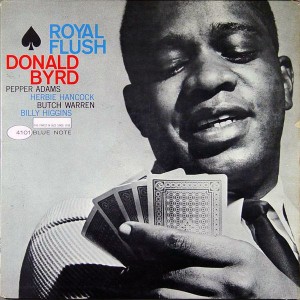

Donald Byrd

“Requiem” from Royal Flush

(Blue Note, 1961)

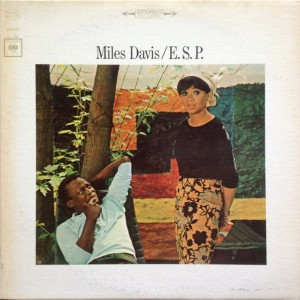

Miles Davis

“E.S.P” from E.S.P.

(Columbia, 1965)

Sly & The Family Stone

“Thank You For Talking To Me Africa” from There’s A Riot Goin’ On (Epic, 1970)

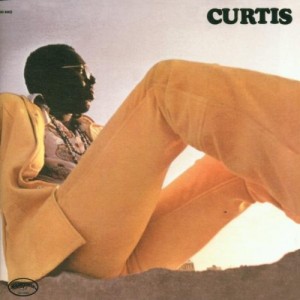

Curtis Mayfield

“If There’s A Hell Below We’re All Going To Go” from Curtis (Curtom, 1970)

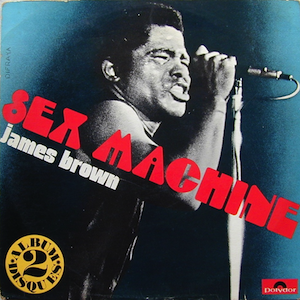

James Brown

“I Don’t Want Nobody To Give Me Nothing” from Sex Machine (King Records, 1970)

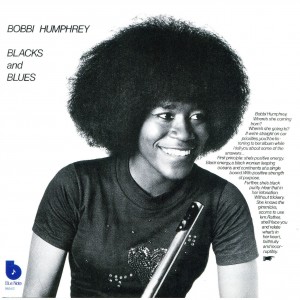

Bobbi Humphrey

“Harlem River Drive” from Black And Blues

(Blue Note, 1974)

Donald Byrd

“Lansana’s Priestess” from Street Lady

(Blue Note, 1973)

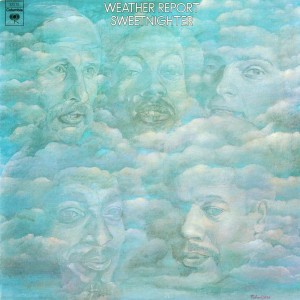

Weather Report

“Will” from Sweetnighter

(Columbia, 1973)

Herbie Hancock

“Quasar” from Crossings

(Warner Bros. Records, 1972)