Published on

December 14, 2017

Category

Features

Following our rundown of the year’s must-hear reissues, Oli Warwick investigates if the unprecedented exposure of obscure albums like Midori Takada’s Through The Looking Glass on YouTube is beginning to guide what records are being reissued.

As online streaming embeds itself into the firmament of music culture, we’re faced with the strange proposition of having new discoveries fed to us by machines. Where once musical discovery was a wholly human endeavour, from digging to chatting to reading to good old-fashioned hearing, now it’s just as likely that a computer algorithm can be responsible for sending new artists your way based on arcane formulae supposedly reacting to your previous behaviour.

While services like Spotify keep their statistics close to their chest, the very public nature of YouTube means it’s possible to observe surprising trends in music listening. There are notable and often curious stand-out albums seemingly picked up by the YouTube algorithm, popping up in huge numbers of listeners’ feeds and scoring play counts that would satisfy a major label pop act. These runaway success stories increasingly transcend their online trappings to become real-world represses, leading to significant developments in the careers of artists who might otherwise have faded into obscurity.

The most obvious and recent such phenomenon is Japanese artist Midori Takada, whose early ’80s LP Through The Looking Glass was plucked from relative obscurity through a series of internet incidents, eventually resulting in a full album rip on YouTube that had amassed around two million plays before it was taken down. After a sizeable buzz, the album was finally reissued earlier this year by two labels working in partnership, New York’s Palto Flats and Swiss Mental Groove sub-label WRWTFWW Records.

Olivier Ducret of WRWTFWW first heard the album in the early ’90s on a record digging trip to London. “These are dazed memories, almost dreamlike, as that period was,” he recalls. “Listening to it was a unique and memorable moment.”

However, it was only when he rediscovered the album online in more recent times that he reconnected with the record. Similarly, it was online that Jacob Gorchov of Palto Flats truly connected with Midori Takada’s music.

“My first encounter with it, I listened to Through The Looking Glass start to finish,” says Gorchov, “and generally speaking I skip around quite a bit. I’m not really aware of the mechanics of how the suggestions [on YouTube] go, but album streams have much higher play counts than individual tracks, which probably that has something to do with that.”

Although the exact architecture of the mythical algorithm is a closely guarded secret, there are some aspects of its behaviour that are understood, and expounded by those teaching ways to ‘score more hits on video content’ et al. The key factor is a relatively recent shift YouTube made from simply measuring the popularity of a video by its play count, to evaluating the quality of the content based on the percentage of the running time the viewer had watched.

Of course other elements such as user behaviour data all feed into the machine, but it raises the question – does calm, meditative music such as Takada’s have a better chance of success on YouTube because a listener is more likely to leave it humming in the background while surfing the internet? In the attention-deficient routine of ploughing through online content, the stillness of ambient music can be considered a tonic of sorts. There are scores of other YouTube ‘hits’ that are noticeably ambient in nature, from Software’s Digital-Dance to William Basinski’s Watermusic II.

“It’s true about overall play time being measured,” Gorchov agrees, “but that doesn’t explain how it might recommend some specific type of music. I’ve noticed a theme in the general appraisal of Midori Takada, where people talk about the calming nature of it. I wonder if the engineers at YouTube are aware of the impact [the algorithm] has on the consumption of various kinds of music?”

It’s a pertinent question: is this influential promotion of ambient music on YouTube a conscious design aspect of the algorithm, or is it an unintended side effect determined by the experiential learning of the machine? It’s not clear whether the mechanics of the website react differently for music to, say, woodwork tutorials or TED Talks, but beyond the simple fact of suggesting certain music, it’s hard to imagine those responsible would foresee the real-world consequences for an artist such as Takada. Before the resurgent interest in her music, she was primarily working on composition and performance for theatre productions in Japan. Now she has already completed one acclaimed European tour, with further shows scheduled, and so a whole new chapter in her musical career has begun.

“This has had a domino effect for her,” Gorchov says of Takada’s rediscovery in the West. “She’s been afforded these opportunities she never would have been able to before.”

Following the success of shows at London’s Barbican, Paris’ Palais de Tokyo and Berlin’s Hebbel am Ufer, Gorchov has been looking for the appropriate space in New York to showcase Takada’s curious fusion of performance art and minimalist music, uncovering another interesting side effect of YouTube influence along the way.

“We tend to think of Western minimalist artists as part of the canon in an institutionalised way,” says Gorchov. “When I speak with institutions here [in New York], it’s not like she’s Philip Glass and it could just happen. What’s interesting is that you have these established artists, but then YouTube has this way of establishing something that’s been historically under-recognised, and the audience currently leans younger than museum or institution audiences in general.”

Palto Flats doesn’t deal exclusively in mining cult Japanese music, but the label did turn heads with a previous reissue of Mariah’s Utakata No Hibi, a sublime and long sought after early ’80s trip masterminded by the prolific Yasuaki Shimizu. A wonder of groove-oriented fusion music it may be, but it didn’t fit Through The Looking Glass’ profile of delicate ambience buffeted by the YouTube algorithm. Its journey to prominence, and eventual reissue, was more abstract but no less fuelled by the power of online communication.

Before the rise of the YouTube machine, music blogs served as a vital conduit for proud diggers to share their most treasured finds from the ephemera of global music culture, often posting rips of key tracks or whole records with impassioned write-ups and artwork scans. Utakata no Hibi first came to the attention of many thanks to JD Twitch posting a track from the record on the Optimo blog back in 2008. While their reach may have been more limited, this culture of music blogs set the tone for the more considered, esoteric end of the modern reissue wave. Mutant Sounds is widely name checked as an influential force, while the well-established Growing Bin label and record shop began with Basso posting his own curious finds on a blog.

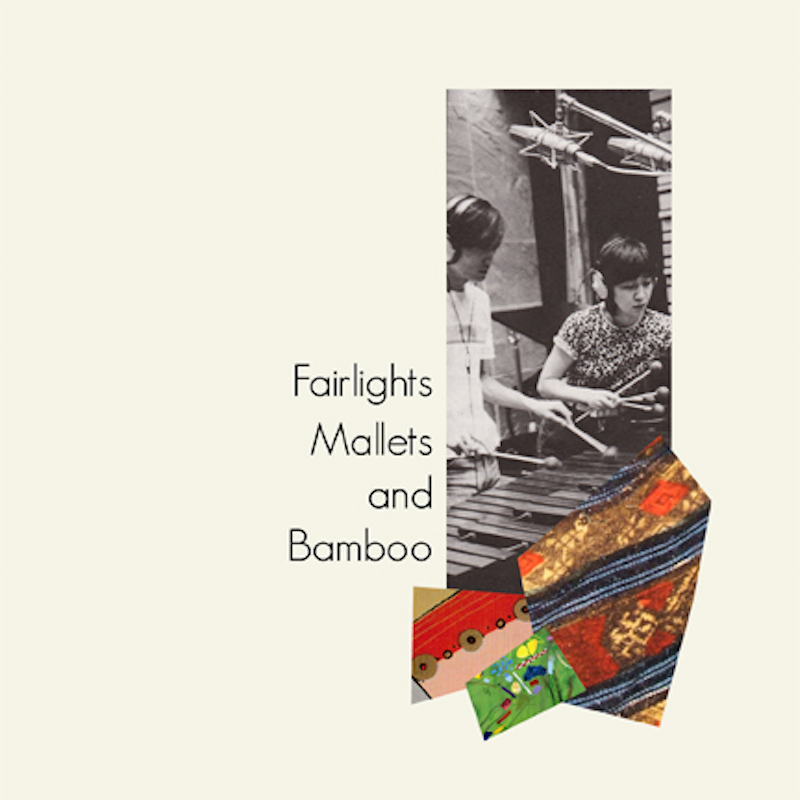

U.S. label Root Strata started life as a blog that dealt very much in this realm of obscure and exotic sounds, with label owners Maxwell August Croy and Jefre Cantu-Ledesma going on to release huge swathes of new ambient and experimental sounds on a variety of formats. Croy, a long-time, dedicated sponge for Japanese culture, even admits that he posted a full rip of Takada’s Through The Looking Glass in 2013, having checked first that it was wholly unavailable at the time. However it was Spencer Doran’s Fairlights, Mallets and Bamboo mix, contributed to the Root blog in 2010, that introduced Croy and many more to the sub-sect of 1980s music from the Far East that Midori Takada, Yasuaki Shimizu and many others had orbited.

“The Fairlights… mix was one of the early things Spencer contributed to the Root blog,” explains Croy over a Skype call, freshly returned to Berlin from one of his regular trips to Japan. “It just blew my mind because I was like, ‘How did I miss some of this?’ Of course I was familiar with some of the Y.M.O. related projects, but much of it, like Yasuaki Shimizu, I’d never heard before. Spencer would say the YouTube software suggestions are more responsible for the resurgence and interest in the music… I like to say it’s his mix. That was the incentive for me to take some real action.”

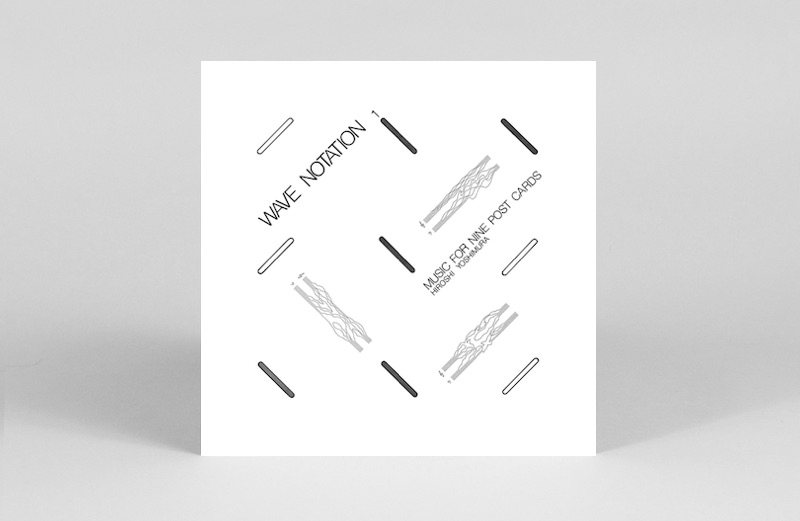

Now Croy and Doran are starting a new label together called Empire Of Signs (a reference to philosopher Roland Barthes’ musings on Japan), and their first release is the late Hiroshi Yoshimura’s Music For Nine Postcards. Yoshimura was noted as a composer of ‘kankyo ongaku’, or environmental music, and wrote extensively about the impact of sound and music on spaces. The album is a certifiable YouTube big-hitter, appearing regularly in listeners sidebars along with Yoshimura’s other lauded album, Green, but the move is far from a cynical numbers game – the label has been in development for a long time. The time Croy has spent with Yoko Yoshimura (who looks after her husband’s estate and legacy) suggests a dedication to the end product beyond selling copies of a popular record.

“We’ve been working on this project for years,” affirms Doran, “long before it was ‘popular on YouTube’ so it had no influence on our decision to re-release the music. From the perspective of someone trying to work directly with the artist’s estate to present his music in full context, I can’t say that it’s not frustrating. Honestly though I think it does the music a disservice to route the discussion towards how much they sell for on the second hand market or how they’re popular on YouTube, and away from the musical content itself.”

Croy meanwhile muses on the dichotomy between the automated listening experience of many discovering Yoshimura’s music, and the artist’s own ideas about the relationship between music, environment and listener. “The current technology of music consumption encourages passive listening,” he argues. “Whether that’s good or bad I don’t know, but I will say active listening is important, for example the act of finding, buying and putting on a record, and that’s one of the reasons that we’re doing this on LP. These kinds of things would be important to a person like Hiroshi Yoshimura.”

Either way, the numbers are undeniable, and highlight a tacit link between the niche influence of music blogs and YouTube’s widespread dissemination of cult sounds to an ever-broadening audience who might never have come across these artists of their own accord.

“As someone who initially came across this music by putting in the actual work of sifting through the physical media I can’t say it’s not a little strange,” Doran admits, “but I’m all for taking music out of the insular limbo state of record collector fetishization. It can certainly be a positive thing if the artist or their estate are being properly compensated, or if they had a sense of control over the way the work was being presented, though sadly neither is true within YouTube’s system of monetization.”

While the phenomenon may not be exclusively focused on Japanese music, there does seem to be a high quantity of Japanese music from the 1980s receiving favourable treatment from the YouTube algorithm. In particular, the smooth, funky sounds of City Pop are reaching staggering numbers of pleasantly surprised listeners. Miki Matsubara’s ‘Stay With Me’ has amassed nearly five million views, prompting Skooma Much to comment, “Youtube recommendations are getting crazy.. I like it.” Ivan Linares replies with perhaps the most pertinent point of all; “they just keep getting better! It’s crazy to think how good a computer can tell what you like or what you are likely to appreciate. Would there be a time when technology will tell everything about us? Maybe they already know us better than ourselves.”

This all has parallels with the recent algorithm-powered rise of artists such as DJ Boring and Ross From Friends, lumped together under the ‘lo-fi house’ banner. In the case of Boring, whose ‘Winona’ track was such a resounding hit, it’s believed a key factor in the strong performance of the track is the image of Hollywood actress Winona Ryder on the record artwork.

Could it also be about the cats though? Cats power a sizable chunk of internet traffic, and the world of Japanese music reissues is not seemingly immune to this condition. Yasuaki Shimizu released the wonderful fusion album Kakashi in 1982, and at present the album rip stands at well over one million views on YouTube. Rather than being targeted at lovers of leftfield music, it’s also likely that the image of the cat on the cover may have both enticed users to click, and inspired YouTube to suggest the album to lovers of cat videos (of which there are many). The comments section once again supports this theory. Palto Flats and WRWTFWW have repressed the album, which is set for release at the end of November.

While there may be faceless, automated mechanics driving strange new trends in music culture, those involved still stress the final experience is a resiliently human one.

“We feel there’s more at play than just the algorithms here,” say the WRWTFWW Records crew. “The incredible artwork of Through The Looking Glass catches the eye immediately. You automatically want to know about the world hiding behind it, and once you discover that world, the music…it’s almost like an antidote for daily stress. In a way Through The Looking Glass became a kind of chill pill you wanted to pass on to your neighbour. YouTube was the conduit, and algorithms helped pointing people the right way, but it’s definitely humans that truly made the album a success.”

Illustration by Patch D Keyes.