Published on

October 19, 2016

Category

Features

David Pescovitz and the team are on a mission.

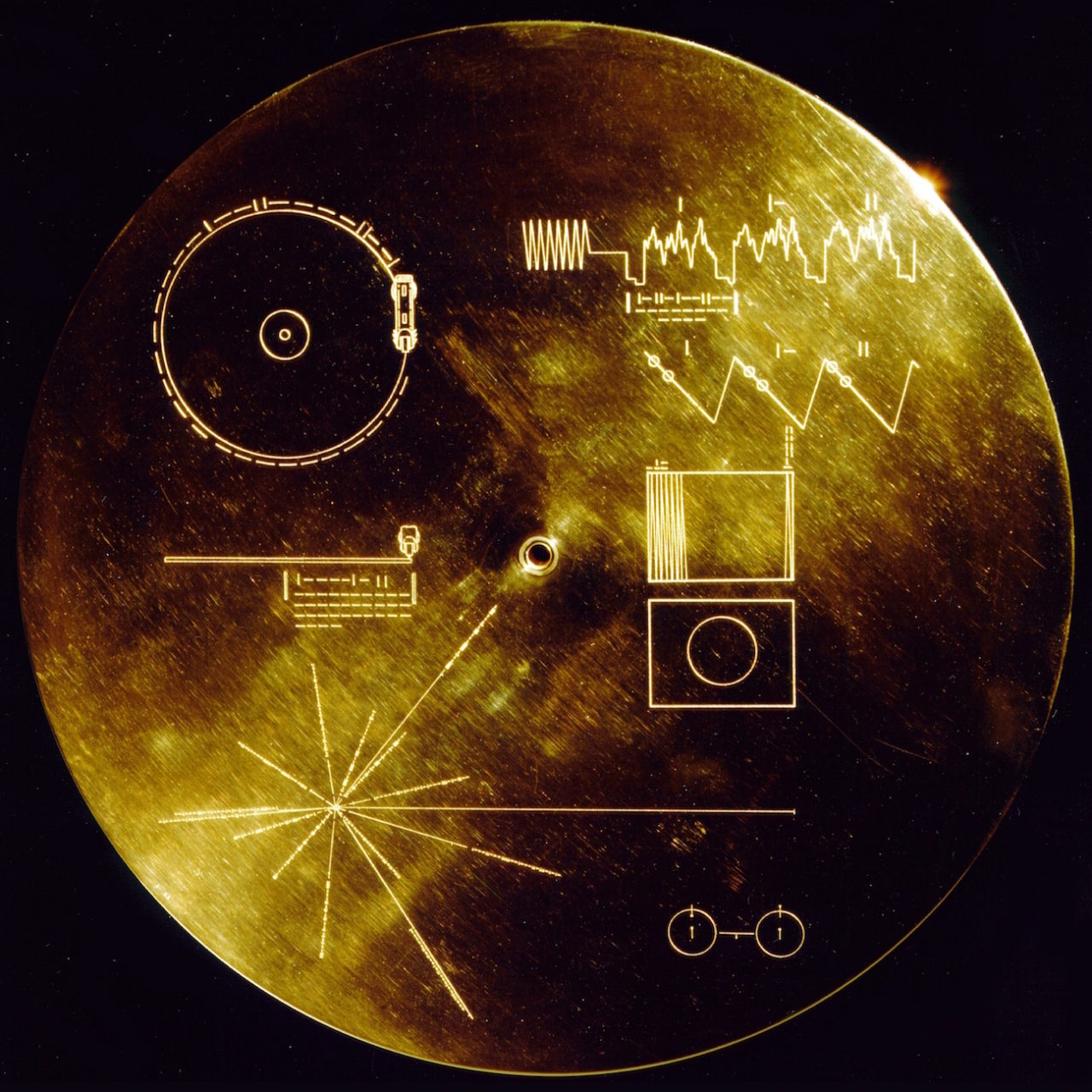

The Voyager Golden Records are without doubt the rarest records in the universe. Pressed onto gold-plated copper phonograph discs and cut at 16 1/3 rpm, they are the ultimate human time capsules, containing music, field recordings, photos and an alien-friendly DIY turntable kit to play it back. Launched in 1977, they are currently billions of miles from Earth on the Voyager I and II spacecrafts, drifting further and further from your record collection. By the time you finish this article, they’ll be roughly another 20,000km further away.

You may never get your hands on an original – Carl Sagan who masterminded with project with NASA didn’t even get a copy – but, thanks to David Pescovitz, Timothy Daly, and Lawrence Azerrad, you can now experience it on vinyl for the first time.

Seven years old when the Voyager spacecraft left Earth, David has, like practically every other record collector we’ve spoken to, been enthralled by the artistic, scientific and downright utopian potential of the Voyager Golden Record. A phonograph record, included alongside the most cutting edge technology of the day, as a message of hope from Earth to unknown extra-terrestrial civilisations, or as the inscription on the record reads: “To the makers of music – all worlds, all times.”

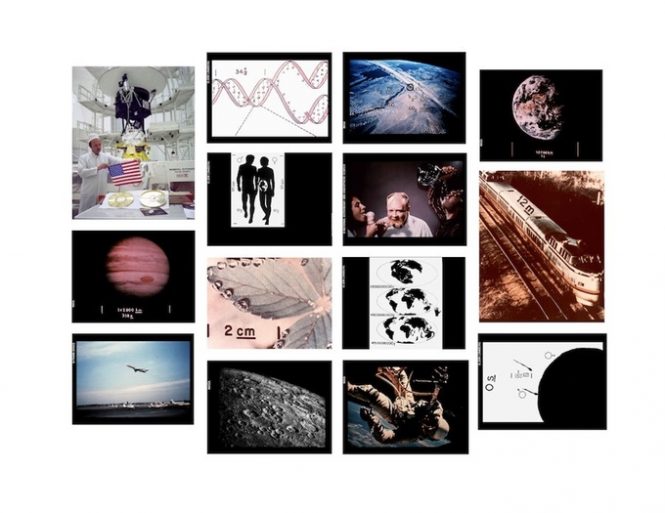

From popular music to dogs barking and the brainwaves of Sagan’s future wife Ann Druyan, the collected visual and sonic ephemera paint a diverse picture of Earth, recognised by project member and Amoeba Records manager Tim Daly as quite possibly the first ever ‘World music’ compilation.

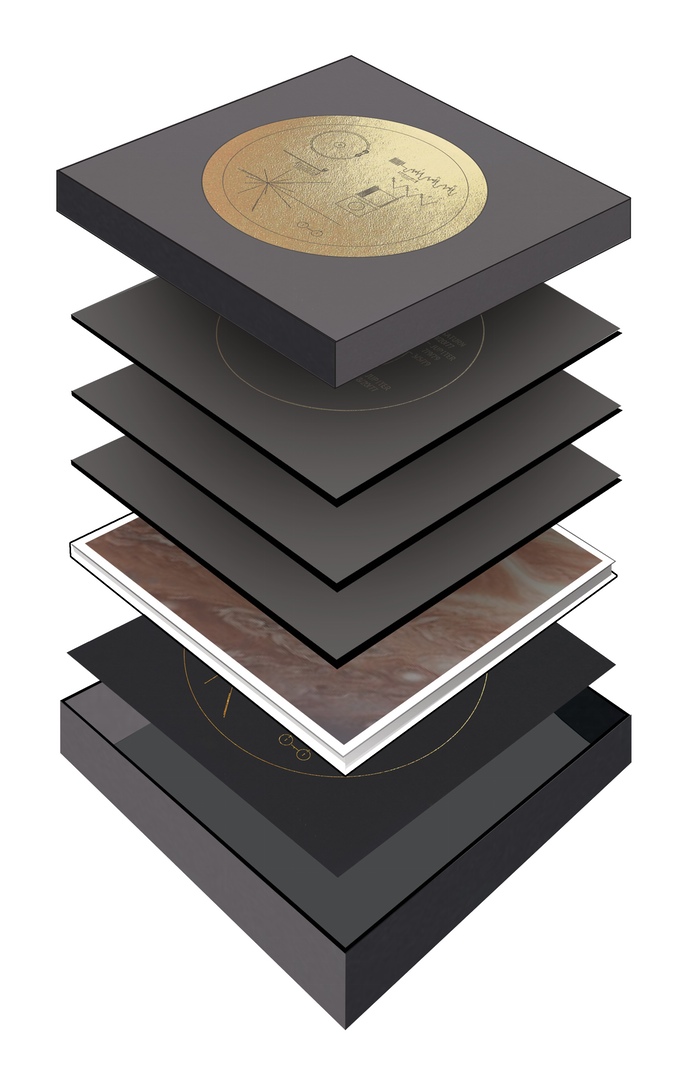

As the Kickstarter campaign to release a 40th anniversary box set draws to its conclusion, exceeding its target five-fold and raising $1.2million at time of publication, we caught up with David Pescovitz to talk about why the Voyager Golden Record still resonates with so many people.

Where does your story with the Voyager Golden Record begin?

When you’re seven years old, which I was at the time of the Voyager launches, and you hear that NASA has approved a group of very smart and creative people to make a message for extra-terrestrials and put it on a phonograph record and attach it to a spacecraft and launch it into space, how can that not be inspiring?

That stuck with me for my life, and I would think about it from time to time. Then, in the early 1990’s when I went to UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism, I went to study under Timothy Ferris the science writer, who produced the original Voyager Golden Record. He was on the committee and the committee was led by Carl Sagan of course. I used to pepper Tim with questions about the project, even back then.

It’s quite a leap from admiring this thing from afar to being the guy who’s going to actually release the thing.

I’m a fanatical vinyl collector and my ten year old son and I would frequently go to Amoeba records in San Francisco and we became friends with one of the managers there, Tim Daly. Tim and I have shared interest in avant-garde music, experiemntal music, contemporary classic, drone, these kinds of things and we would talk. He was also interested in Boing Boing, which is the site I co-edit and also Institute For The Future which is the non-profit where I’m a research director.

So Tim was thinking about technology and the future and those kinds of things and he said “wouldn’t it be great if we could reissue, or actually issue I should say, the Voyager Golden record on vinyl for the first time?” And we laughed and said that would be amazing, and then a few days later I texted him and said, “I’m going to actually reach out to Tim Ferris”, who I’ve kept in touch with since graduate school and who’s been encouraging to me over the years and a supporter and a friend. I had lunch with Tim and he was incredibly enthusiastic, and he said “you guys should definitely do that, go for it, do it!”

Where do you even begin to get a project of this magnitude off the ground?

Well, that was about a year ago, and at that point we started reaching out to the other living members of the original committee and contacted a group here called the Rights Workshop, which is a very respected rights music supervision service, and together we began the daunting task of clearing the rights to all of the music and the 115 images that were encoded in analogue and put on the record.

The Rights Workshop also started reaching out to organisations like National Geographic who hold the copyrights to some of the images. A lot of them are held by individual photographers, so I was tracking people down online and emailing relatives and hearing fantastic stories when I finally reached the people.

From there we worked very quietly on this project, and then when it became clear that we were ready to go and had made real progress, we reached out to my friend Lawrence Azerrad, who is a very talented designed in Los Angeles. He designs most product packages for Wilco, he’s done stuff for Best Coast, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Miles Davis all of these guys. So he got engaged, and the next thing we knew this thing was happening.

Aside from all the people who you’ve included in the project, it feels like a lot of people have quite a personal connection with the Voyager Golden Record story…

I think so, and I think it’s because it lies at the intersection of science, art and music as a way to spark the imagination and give people a sense of hope and possibility and a little bit of optimism. And I think that quite honestly, we’re jonesing for a dose of hope and optimism right about now.

We were very realistic when we put our Kickstarter goal of approximately $200,000 and we did projections that if we could do 2,500 of these then it would make sense and the interest and the excitement about it has just absolutely been astonishing. I’m hearing so many stories from people about how the Golden Record has touched their lives or impacted them in some way.

Are any of those personal stories on the tip of your tongue?

One of the photographs on the Golden Record has a child in the picture and I had the name of the photographer and I was doing deep Google magic trying to find the person. I finally emailed someone I thought I had identified and I get a phone call, and the person says they’re not the photographer – that was their father – but that they are the boy in the photo.

And then we had an hour long conversation about all kinds of things, about photography, about the oceans, about the Golden Record, it’s really wonderful. There are just loads of those kinds of stories that come out when there are so many people who contributed to this project when it went up. There was the committee of course and then there was all of the people, whose work or whose recordings were included.

And ultimately it was a utopian vision for Earth as much as an actual attempt to communicate with extra terrestrials… Wasn’t it?

Yeah I think the idea is that if there is a civilisation that is intelligent enough to actually intercept it, they’ll be able to follow the instructions on how to play it. And I think that’s true. In some ways though, it doesn’t even really matter if it’s ever played or not by an extra-terrestrial civilisation.

And I firmly believe this, it was a gift to the cosmos but it was also a gift to humanity. And Linda Salzman Sagan, who was on the original committee, said something along the lines of there being two audiences, there was the extra-terrestrial audience and then there was the audience of the people on Earth. And that’s what’s exciting to us.

So in a sense this is for the second audience on Earth that never got to hear it either?

Yeah, I don’t want to say that they never got to hear it, because you can hear it online in various places, the NASA site has a lot of the audio, people have scanned the images from various places and uploaded them. But I don’t think you can experience it the way that we’re presenting it here, which is on record with this beautiful book.

There was a nice box set issue of it in 1992 with the fantastic book Murmurs Of Earth that was written by the original committee members and they re-printed the book and included a CD-ROM with the contents of the Golden Record. But that project is obviously long out of print, I mean who plays CD-ROMS? It has never been issued on record and that was the way it was meant to be played. Obviously the one in space was a actually a gold-plated copper disc, but on phonograph record.

For someone who runs a technology site and is a director at the Institute For The Future, the physicality of the object still seems reamrkable important to you.

Yeah, for me that gets at why I collect vinyl. I’m not one of those people that has a stereo that’s good enough to really tell the kinds of quality that people talk about vinyl, but I can tell you that I think we spent so much time in virtual mediated digital experiences that we have this innate desire for physical, tangible, authentic experiences and objects.

And that’s why I like vinyl, I like the ritual of picking the record I’m going to listen to and getting it out of the sleeve and looking at the sleeve and even dusting off the record and putting it on. I think that that also is something that touches a lot of people, and obviously we’ve seen that with the vinyl resurgence, and it’s not because most people can really hear the difference on their home stereos.

Do you have any favourite recordings from the collection? pieces the resonate particularly?

Totally. So there’s two. One is Blind Willie Johnson’s ‘Dark Was The Night’, which is a vocal piece but it’s non-lyrical and it has his unusual slide guitar. That piece is so haunting and so moving, it has always meant a lot to me. And also there’s the Sounds of Earth, which is a 12-minute audio poem which Ann Druyan created with the support of other committee members. That is field recordings including the likes of insects and birds, a baby and mother and a kiss and it’s montaged together in what is almost like a piece of avant-garde tape music. That’s always been a fantastic piece for me.

I was going to say, when you mentioned your interest in avant-garde and experimental music, this immediately sprung to mind.

Absolutely. And Tim my partner on it, he found out about the Golden Record because of Laurie Spiegel’s piece on there which is this beautiful computer music rendition of Kepler’s Harmonices Mundi. That piece actually opens the Sounds Of Earth, there’s just a small section of Laurie’s piece. Tim was really interested in that piece of music and then found out it was on a record that’s now 13billion miles from Earth.

What informed the committee’s original choices of music?

They wanted it to reflect the myriad cultures and the history of music on Earth. That said, there are also limits, if only in the duration of what could be included, even at 16 and 1/3 rpm, which is how they mastered it so you could hold as much as possible on the phonograph record.

But they were also limited by time, they only had a few months to put this thing together which means identifying the music but also sourcing it and clearing the rights. They had to clear “universal rights” to these recordings and they reached out to an amazing community of experts to help inform their decisions. People like Alan Lomax and others gave their input. Then ultimately they selected pieces that moved them the most. And I think that, sure you can criticise it, but I do think that compilation of music stands the test of time as some of the most beautiful music on Earth.

And there’s really interesting stories too. They had wanted The Beatles’ ‘Here Comes The Sun’ and Tim Ferris reached out to The Beatles who were all living at the time and they were all very excited about it. But it turned out the label owned the copyright of the song and as I understand wanted a lot of money to include it and the project was basically done on a shoestring so it sadly wasn’t included.

My partner on this Tim Daly is like a walking encyclopaedia of music. He sees the Voyager Golden Records as almost the first world music compilation, before “world music” was a genre. And I think as that it’s a fantastic portal to musics of other cultures and other places and other times. I’m hoping when people hear this as a compilation, and as a collection of music it will spur them to explore the kind of musics that are represented there more deeply.

How far down the line are you with the conception and creation of the box set?

We’ve done drafts of the design that you can see on the Kickstarter site and also identified the materials and the various partners who are going to do the manufacturing, the vinyl pressing, the book and the printing. Basically what’s going to happen is once the Kickstarter ends we will go to work on mastering for the vinyl and also collecting materials for the book. We have the images, but obviously there’s essays we want to include and other ephemera from the mission. We’re going to have the entire thing ready and shipped before the 40th anniversary in August next year, and probably before that.

Given how successful it’s been so far, will you have to adapt the number of records you press?

One of the most beautiful parts about it being on Kickstarter is that we will know exactly how many pledges there were for the box set and then we can base our manufacturing on that number. And this 40th anniversary edition of the Voyager Golden Record won’t be produced again. We don’t have any firm plans beyond the Kickstarter but I can tell you that this version is not going to be reproduced.

And the label you’ve set up for this end is Ozma Records…

It’s worth mentioning the name. So Ozma is the Princess of Oz from the Wizard of Oz books. That’s the first reference. But the second reference is connected to Frank Drake, who is a pioneer in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence, and was on the Voyager Golden Record committee. In fact he’s the one who came up with the idea of sending a phonograph record. In the 1960s he launched one of the first scientific efforts to search for extraterrestrial intelligence using radio-telescopes and that was called Project Ozma, named after Princess Ozma. So we wanted to honour him and use that name. Our hope is to release future records that lie at the intersection of science and art and music too, that also instil a sense of wonder.