Published on

July 8, 2019

Category

Features

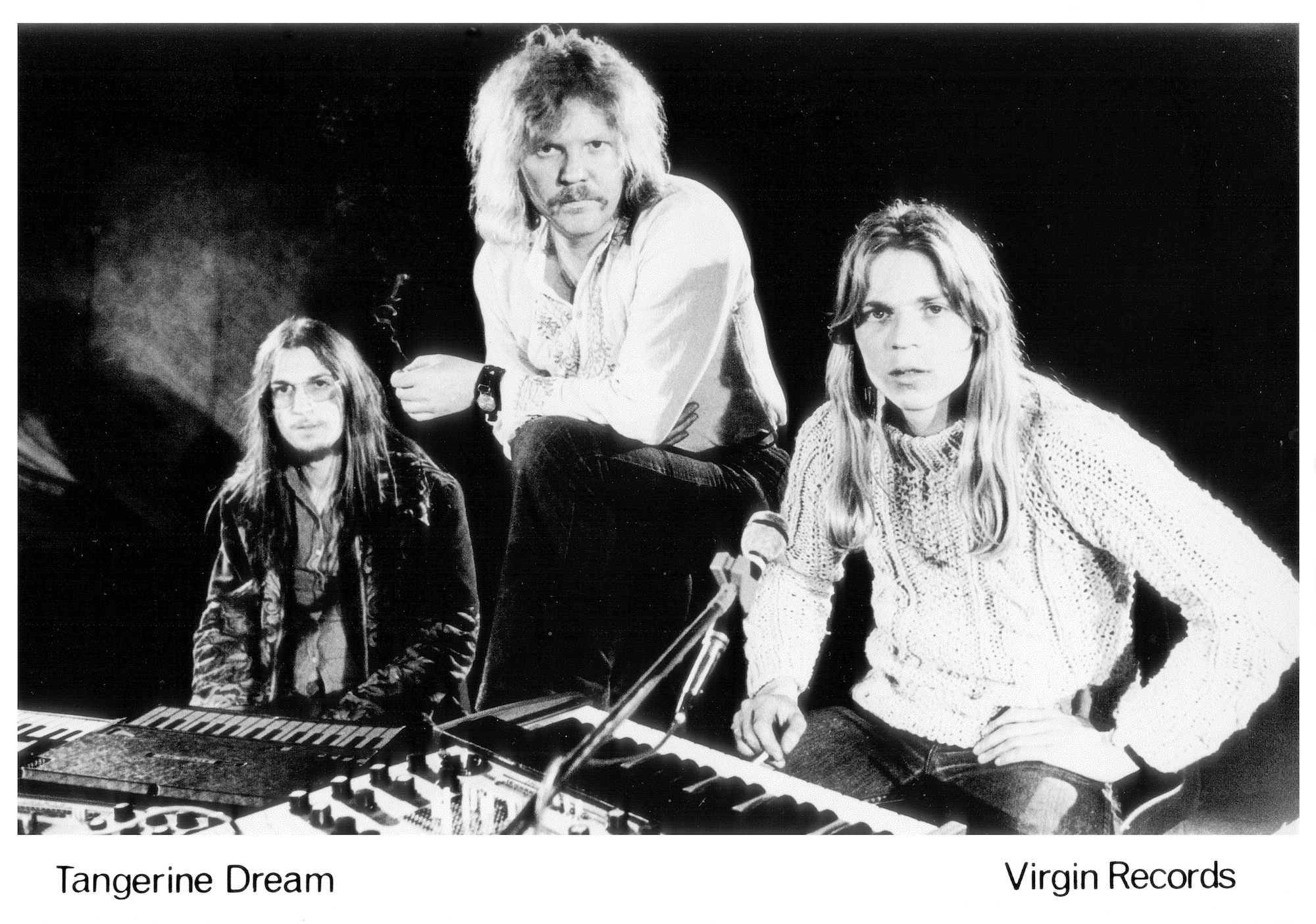

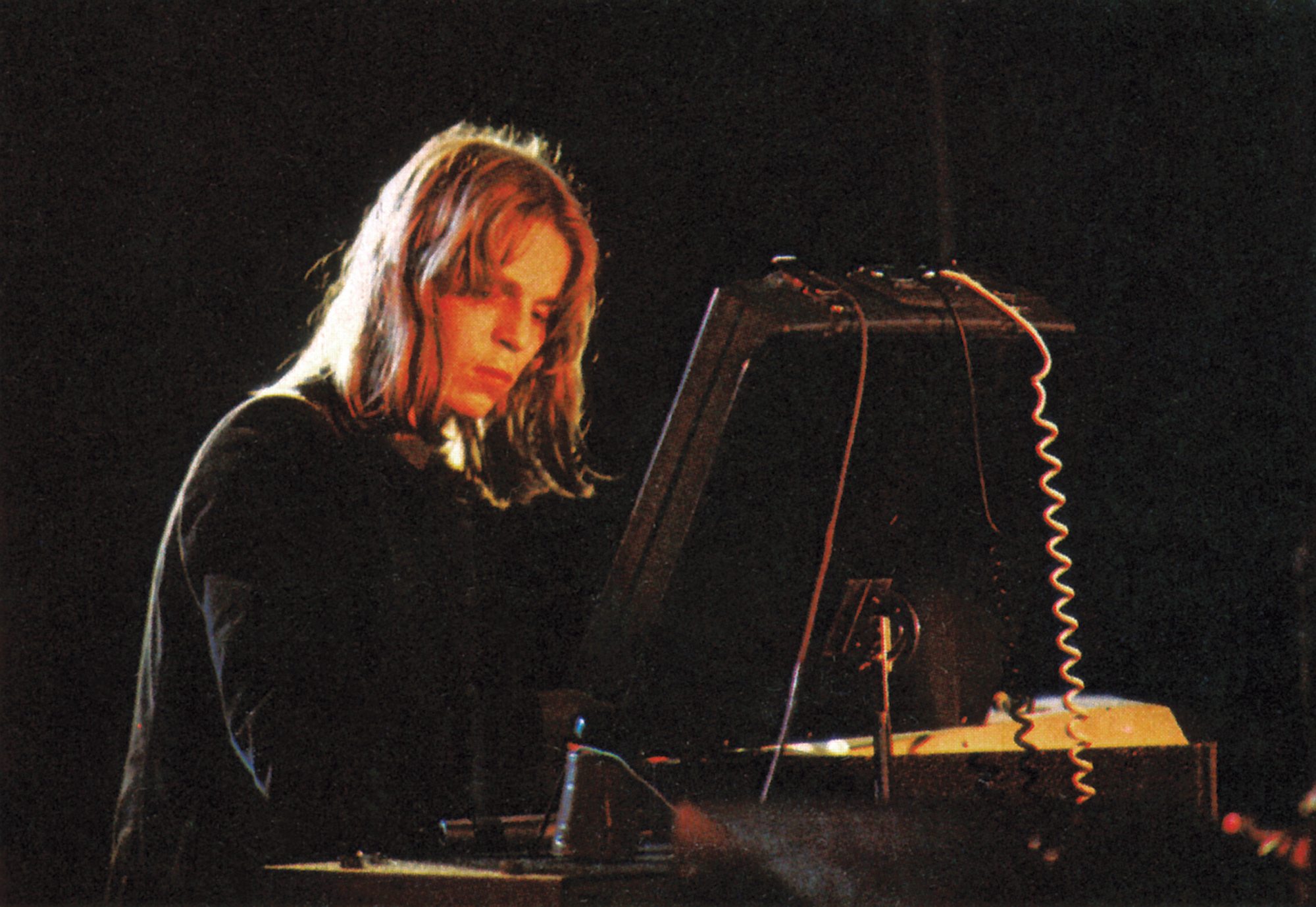

Formed in 1967, electronic pioneers Tangerine Dream’s golden era is chronicled on the monumental new box-set In Search of Hades: The Virgin Recordings 1973 – 1979. Peter Baumann played keyboards with the band for most of this period. He talks to Chris May about reining in ‘wild’ synthesizers, studio improvisation and the band’s prolific recording sessions.

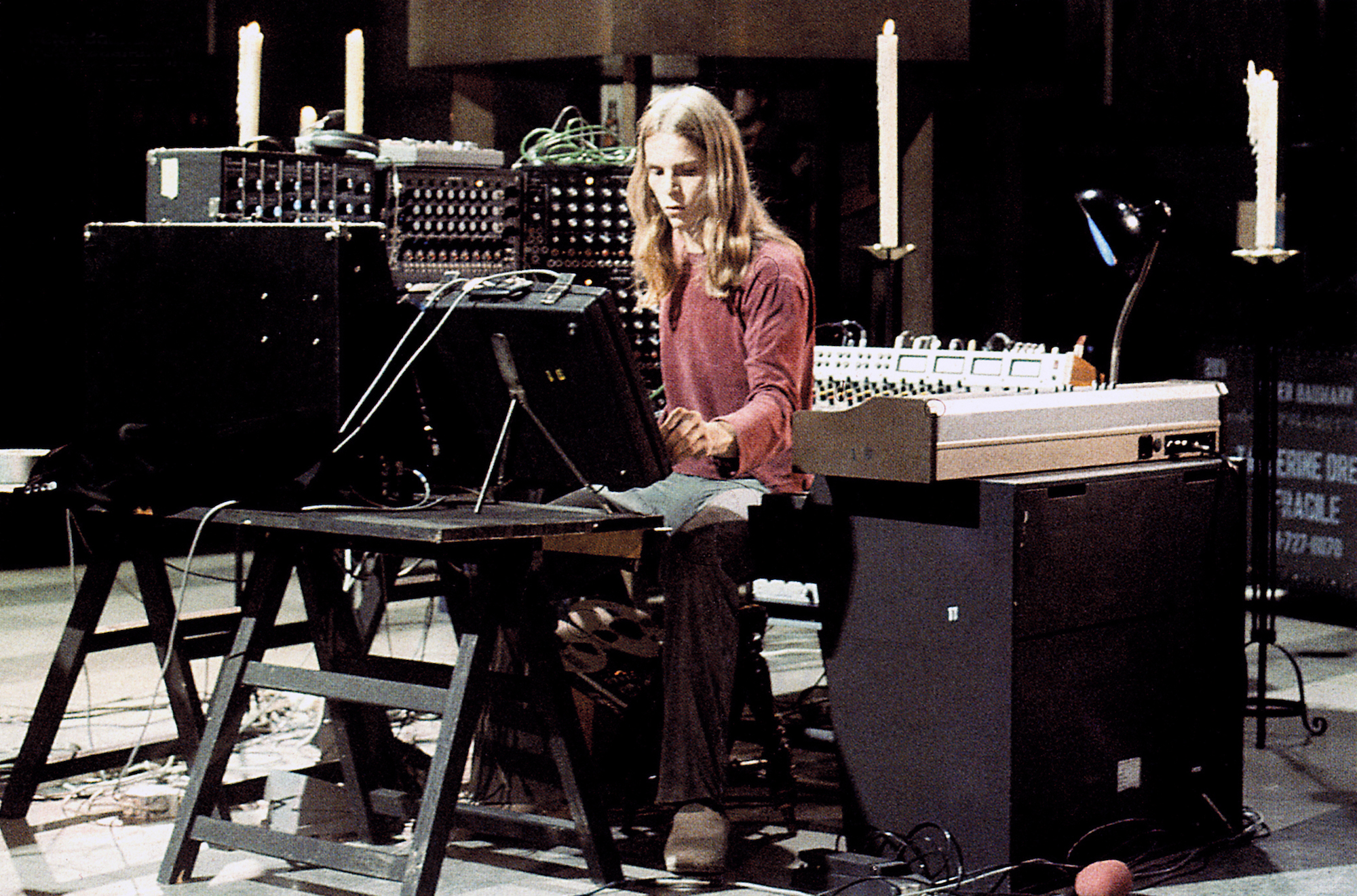

Peter Baumann joined Tangerine Dream in 1971. The group was in the final stage of its transition from guitar-based rock band to keyboard-focused kosmische outfit, a process it would complete in 1973. For the six years he was with the group, Baumann’s colleagues were founder-member guitarist and keyboardist Edgar Froese and drummer and keyboardist Christopher Franke.

Tangerine Dream was struggling to find an audience in 1971. Record sales were poor and it was not unusual for the band to be pelted with rotten fruit and vegetables at gigs. Instrumental music was a hard sell, but change was in the air. Early in 1973, the band’s Mellotron-infused album Atem was taken up by DJ John Peel. That autumn, Virgin’s Richard Branson – watching Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells morph from niche success to mainstream smash – was looking for another instrumental hit. He signed Tangerine Dream and rushed the band went into the studio to record Phaedra. Released in 1974, the disc made the British Top 20 albums chart. Their US breakthrough came hard behind.

After Phaedra, Baumann played on a string of landmark Tangerine Dream albums including Rubycon, Ricochet and Stratosfear, before leaving the band in late 1977.

Photo: César Rubio

The story goes that you passed the audition for Tangerine Dream in less than ten minutes. Is that true?

We definitely clicked fast, though I was a really terrible keyboard player. I still am. I never had formal tuition, so I can’t play in a conventional way. For me, music is all about sound and mood, about the experience rather than a string of notes. Edgar [Froese] and Christoph [Franke] were much better players than me, but they could tell I was coming from the same place. I remember it felt like we’d been playing together for years.

The band’s instrumentation was still pretty conventional in 1971, wasn’t it?

Yes, but they didn’t use it in a conventional way. Edgar played guitar, but he didn’t play chords in the normal fashion, and he had all sorts of gizmos to customise the sound, a bit like Robert Fripp. And Christoph was making new sounds by amplifying his drums differently and using found-percussion instruments.

Was the switch to electronics a fast one, or did it evolve slowly?

It was a gradual transformation. Evolutionary not revolutionary. We were always on the lookout for anything that made a different kind of noise and a lot was happening with electronic instruments in the early 1970s. There were step changes of course. Getting a Mellotron was one and getting a Moog Sequencer was another. Those were the two major shifts in our musical set up. There was quite a lot random stuff with the Mellotron and the early synths, which was kind of a bonus.

The early oscillators and sequencers were unpredictable beasts, like wild horses. Particularly in hot weather at outside gigs, they’d go off in their own direction. You couldn’t rein them in. But they were so wonderful we didn’t care.

It all came together in the autumn in 1973 in Oxfordshire. The technology was maturing and we signed with Virgin and went to the country to record at The Manor. It was a wonderful experience. It was beautiful. A lot of things came together at that time and out of them came Phaedra.

And after seven years, Tangerine Dream became overnight stars.

Yes. Either the success of Phaedra validated us or audiences caught up with us. Or both. Younger, hipper audiences had always liked us. But in some places the people would stand around laughing or they’d get angry and throw things at us. We didn’t care. We believed in what we were doing. I guess we thought people would catch up eventually. The negative reactions didn’t really stop until after Phaedra came out.

No-one could have predicted it, but Phaedra and Tubular Bells caught a moment when people became fascinated with instrumental music.

Something was in the air. What I really love about instrumental music is that there’s no linear narrative, it’s just pure experience and pure feeling. Feelings are always in the moment – always fresh and always unique. Every time I listen to Phaedra, it’s always a different record. I’m in a different mood, a different space. There are two worlds, the cognitive one and the visceral, feeling one, and I’m very deeply into both of these worlds.

How much of Phaedra was pre-composed and how much was improvised in the studio?

It was all completely improvised. All the albums were. We never had any idea what we would do when we went into the studio. We would try this, that and the other. And it was never a matter of following a precomposed structure. We never had to ask, shall we do it this way or that way? It was intuitive. I can’t remember there ever being a big discussion about the music itself. It just fell into place. It was always an immersion process. The only one that was a little different was Ricochet, because the basis was recorded live in concert and then we took that into the studio and expanded it a little bit.

How long did you spend making Phaedra?

About three weeks. All the albums took two or three weeks. We worked pretty fast, given that a lot of experimentation went into the process.

The new box set includes the first full-length issue of Oedipus Tyrannus. Why has that album taken so long to get released?

I honestly can’t remember. We weren’t interested in release schedules and stuff like that. We left it all to the record company. We just wanted to make music. We signed the contract with Virgin without knowing what was in it. I did most of the talking because I spoke English better than the others. We just wanted to get back into the studio. We were focused on the music to the exclusion of everything else. We never had a manager. We had someone who organised the tours, Gram Stewart, because we toured a lot. But we never had a business manager who would deal with the record company on our behalf. I don’t think it ever occurred to us. We were just too absorbed in making music.

Which is one reason you made such extraordinary music. Did you realise how revolutionary it was at the time?

We had absolutely no idea. We knew it was different. But we were totally in the moment. We weren’t trying to be revolutionary or influence things at all. It was just what we did.

Do you have any favourites among the Virgin albums?

There are parts of Ricochet that I think hit the high mark, and as an overall piece of music I think Phaedra is one of the best. Rubycon and Stratosfear have a number of times when the groove just came together and it feels very solid. But as a body of work, I enjoy it all.

You left the band for a short while in 1975, then permanently in 1977. What caused the final split?

It just didn’t seem so much fun anymore. We had a lot of success, and a lot of tours, and then it all started to become a little bit too much like a job. Instead of being in the moment, it flipped into “what do we do next?”

I think there was a creative lull in the band. Something had to happen and because Edgar had the name Tangerine Dream, it was clear it was me who was going to have to leave. And I was still young enough to try some other things. There was no big bust up though. We had remarkable little friction in the band. We each had our little corner musically, of what we brought to the table.

I can only remember one major blow up. I think it was while we were recording Stratosfear. There was an hour or so when doors were banging. But it was simply everybody trying their best and being frustrated when they didn’t quite get it right. There was pressure. We had two weeks in the studio before we went back on the road and a new album needed to finished. My memories of being in the band are overwhelmingly good ones.

All photos Virgin Archive (unless otherwise stated)