Published on

May 27, 2015

Category

Features

With the soundtrack to his acclaimed 16mm installation Variation FQ being pressed to vinyl for the first time, we caught up with artist and producer Jeremy Shaw to talk voguing, mushrooms and minimalism.

Words: Dorothy Feaver

Jeremy Shaw’s body of work is steeped with a fascination for altered states of mind – whether through music, dancing, narcotics or religion – and for the limits of language, visual or spoken, in articulating those moments of release. In his charting of grey matter, Shaw plays on the schisms and overlaps between clinical method, outmoded science, science fiction, popular thought and mysticism, trying to narrow down the moments of truth.

He might take a detached view, probing the kitsch, clichéd aesthetic of psychedelia in This Transition Will Never End (2008-ongoing), where he is amassing an archive of clips that show reiterations of a vortex in the movies, representing a transition from one reality to another. But he is also a participant: in the series Transcendental Capacities (2011), for example, Shaw experiments with Kirlian photography, attempting to record the effect of listening to his choice of ‘profound’ music – such as Donna Summer’s ‘I Feel Love’ – by exposing the changing electromagnetic field around his finger when pressed directly onto film. (George Harrison was a notable fan, using Kirlian photographs of his hand in 1973 for the record sleeve of Living in the Material World.)

Born in Vancouver, and based in Berlin since 2007, Shaw straddles both the art world and the music industry, having had an active career in electronic music under the moniker Circlesquare. When music surfaces in his artworks, it’s often a decisive factor. In the dual film projection Best Minds (2007), straight edge dancers are captured in slow motion, but it is the ambient soundtrack, with its use of deteriorating tape reels, that illuminates the experience of apotheosis through dance.

Shaw’s videos, photographs and installations can take on an anthropological aspect, documenting the rites of subcultures from tie-die to drug-taking to raving, yet they exude a sense of homage. So too, under his hands, archive material is injected with the protean quality of science fiction, as seen most recently in Quickeners (2014), where Shaw manipulates black-and-white footage from a 1960s documentary about a Pentecostal Christian sect in West Virginia. A dowdy church hall it may seem, but this is an isolated group from a superhuman future who are devolving from the Quantum Human network to display what the narrator calls ‘human’ characteristics, such as thinking irrationally and speaking an unintelligible language (Shaw has manipulated the voices). In the ecstatic climax, the Quickeners dance with snakes and shake uncontrollably, irradiated by colour – seemingly reconnecting with the old-world human mind – as the logical Quantum Human narrator is drowned out by a surge of sound.

Could you describe the film Variation FQ (2011–13) for those who are listening to the vinyl?

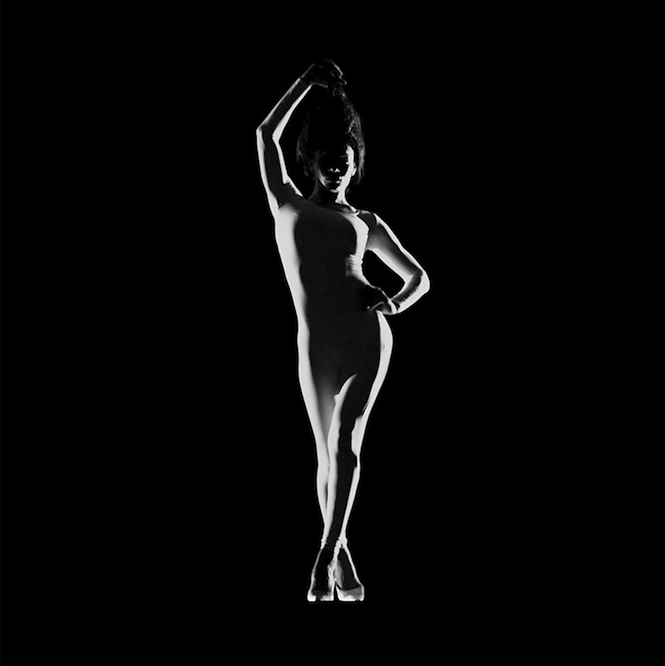

The film sets legendary voguer Leiomy Maldonado starkly lit from the sides against a black void in which she performs her signature dance style – teetering between elegance and violence. As the piece progresses, slow motion and step-and-repeat style visual effects are introduced to create a ghostly layering and repetition of her image in her most virtuosic gestures. It’s an 11-minute long black-and-white work on 16mm that centres around this positing of Leiomy’s contemporary dancing within the formal visual style of a 1960s ballet film.

How did you first encounter voguing and ball culture?

Undoubtedly the first time I would have encountered it would have been watching Madonna’s ‘Vogue’ and Malcolm McLaren’s ‘Deep in Vogue’ – not sure which I saw first but neither had much resonance with me at the time. The next encounter would have been seeing Jennie Livingston’s film Paris is Burning [1990] around 1995 or so, which made a huge impact. It wasn’t until summer 2005 though that I really saw it again – when Eli Sudbrack (Assume Vivid Astro Focus) curated a 12-hour video programme at this place just outside of Portland called The Fruit Farm. I was super high on mushrooms at the time and amongst Kraftwerk and B52’s and Leigh Bowery videos, he had programmed all these low-fi vogue clips that totally blew my mind. I kept asking him to play them again because they were so fast and shaky and exciting that it was really hard to grasp it all on first viewing.

And how did you reach out to legendary voguer Leiomy Maldonado?

I wrote her on Facebook. I was living in New York in 2011 on a residency and had attended Vogue Knights and some other balls but hadn’t had the opportunity to meet her. So I wrote her cold and she wrote back right away and we arranged to meet. I brought along Pas de deux on my laptop and we sat in a diner and watched it.

In Pas de deux (1968), Norman McLaren slowed and multiplied the movements of one then two ballet dancers into an entrancing spectacle: When did you discover it? Did you feel like you’d found a kindred spirit in McLaren?

I first saw Pas de deux in elementary school one lunch hour. Sometimes when the weather was super bad they would play films so we didn’t have to go outside. I can’t remember anything else that we watched during these hours other than Pas de deux – it haunted me for years. I rediscovered it during art school on an NFB [National Film Board of Canada] compilation and was able to watch it repeatedly and scrutinize what it was that I’d been so drawn to – which was the step-and-repeat optical printing effect that had sparked my pre-psychedelic imagination. I think as a kid, it seemed to me as though McLaren had captured real ghosts on film – not the kind I’d seen in movies, but like an actual document of someone’s supernatural other. I wouldn’t say I found a kindred spirit, but there is something in that effect that truly permeated my mind and continues to influence me to this day.

So how does it feel for you to unite these personal heroes – this iconic 1960s film with the voguing star? Eerie?

No, it felt really natural. I mean it was a long and gradual process when I think about it – having the film running through my head since I was a kid and following Leiomy on YouTube for a few years before working with her. I shot it in 2011 and kept getting stalled with editing, so it wasn’t actually completed until 2013. I don’t think I was ever consciously thinking about it this way, but yes, it is a kind of melding of two minds that I have found greatly inspiring.

What came first in the production, the performance or the music? Was Leiomy responding to your music or did you respond to Leiomy’s moves?

The performance came first. I began writing the music in response to the footage once it was viewed in slow motion and was editing and composing in tandem as I went along.

Is it fair to say that there’s a duet going on, in the sense of the collaboration between you and Leiomy?

I guess you could say it’s a duet, but more in the idea of a kind of call-and-response type way. She freestyled nearly the entire time we shot, so I ended up with this wealth of one and two minute clips but without any real structure between them before I began editing. From these I created the arc of the film and embellished it with music and effects. Perhaps it’s more of a remix than a duet.

By slowing down Leiomy’s incredibly fast freestyle Vogue Fem, the movements become almost ghostly. Is there a comment here on fringe cultures being plundered for alternative references by the mainstream?

No, it’s not a comment on that. The visual effects are a way of extending the cathartic movements that Leiomy makes. I wanted to scrutinise these moments that I see as almost being superhuman – to zero in on the power and spontaneity of her dancing. She has such a unique way of moving, I sometimes feel as if she is able to manipulate time. By slowing down the document of this and applying step-and-repeat effects in varying degrees, the extension and repetition allows you to witness their extreme physicality and possibly pinpoint exact moments of catharsis. I see it as a way of visualising multiple planes of time at once, not unlike the bullet time effect in The Matrix [1999]. It’s similar to other works of mine where I employ special-effect tropes commonly used to insinuate altered states on film to illustrate documentary moments of what I perceive to be transcendental behaviour.

Sci-fi, altered states, and psychedelia are themes running through so much of your work – can we see (or hear) them surfacing in Variation FQ?

Yes, absolutely. Although there are quite explicit references to psychedelia and altered states in the visual effects and content of the film, to me the piece as a whole is a work of science fiction. Much of what I do these days sees me working with outmoded mediums, documentary subjects and visual effects – attempting to make succinct, solid works that as such throw the date of production and validity of content into question. With Variation FQ, the combination of antiquated 16mm presentation and 1960s aesthetic meshed with Leiomy’s super contemporary dancing and digital elements of the score creates a sort of alternate reality where these disparate elements co-exist harmoniously in their own collapsed time-zone.

The music especially strikes a different mood to Pas de deux. In McLaren’s soundtrack, the classical orchestration has the harp plus the new age sound of the panpipes. Your melancholy notes on the piano owe something to Eric Satie?

Yes, Satie is definitely a reference as well as other minimalists like William Basinski and Leyland Kirby. I wanted the piano and string loop to have a very hypnotic quality to it that was only altered slightly and subtly as the piece went on, mainly via tape manipulations and effects. It doesn’t ever ramp up in intensity, even during the peak of the song when the other elements come in.

Variation FQ at the Schinkel Pavillon, Berlin, June 2013

But there is the switch between mono and stereo – how does that alter the composition?

The shift occurs at a key moment in the film and is used as both a narrative and conceptual device. The mono piano and string loop that wows and flutters along with the 16mm is joined by very wide, digitally chopped and stretched vocal samples. These accompany Leiomy as she steps out of the dark with her hair held up over her head and begins to let it fly – one of the gestures she is most recognised for. At this point the song becomes a kind of push-and-pull duet between the warm, analogue instrument signals and the thin MP3 vocals and subsequent synths.

Watching the film, the whirr of the projector injects the auditory experience with the feeling of devotion that 16mm inspires in its fans. What does it mean to listen to the soundtrack in isolation? Should we imagine a dancer? Should we get up and dance?

I think you should do whatever you feel like doing! I don’t have any real ambitions as to what happens when the soundtrack is listened to in isolation, but I would have to say that the sound of the needle on a record certainly has a similar effect on people that you feel 16mm does to its fans. There’s a familiarity and comfort that it can instil in those with a point of reference for it – instant nostalgia for many – from which you can then subvert. As it’s a pretty meditative song for the most part, it likely won’t incite too much dancing, but I’m all for it if anyone wants to.

There is an added layer of nostalgia to the new record, beyond the quality of the vinyl, because it also throws a curveball back to your music practice. Do you see it as another music release, or an object in its own right?

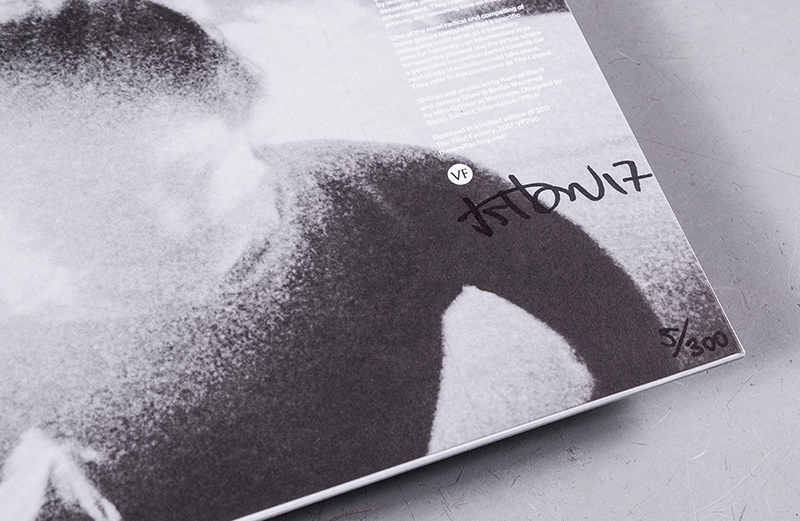

I see it as ephemera from the film. Like any good soundtrack, I think it can stand on its own but we’ve made it a more niche object by silk-screening and hand-numbering and pressing it on white vinyl. I’ve always been drawn to the promotional ephemera and merchandising related to movies and art and music – posters, T-shirts, zines, etc. I’ve collected them since I first saw David Bowie as a young kid in 1987. So it’s really nice to be able to offer things like this related to my artwork, in a similar way that I did when I was working more heavily in music.

How did the record artwork come together – and why white vinyl?

I wanted to keep the same aesthetic as the film itself, so it made sense to have a black sleeve with a white record. It’s also just quite nice to have coloured vinyl, from a collector’s perspective – instantly gives it a kind of aura. The cover and sleeve are both silk-screened with stills taken from the film – the cover being the most iconic moment and the sleeve images are more abstract points where Leiomy is accompanied by translucent multiples of her own image. The design was done by Derek Barnett – someone who I have worked with for many years on my art and music projects and who is also responsible for the titles of Variation FQ and an upcoming book.

Jeremy Shaw’s Variation FQ is out now via The Vinyl Factory in an edition of 300 hand-numbered copies. Click here to order.