Published on

May 1, 2014

Category

Features

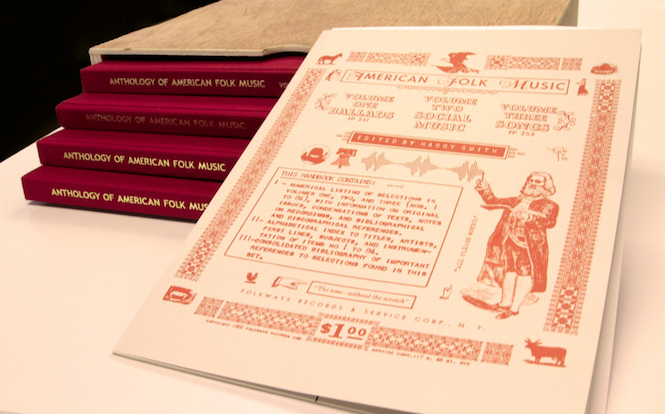

In April, Portland’s clandestine archival label Mississippi Records reissued Harry Smith’s indispensable Anthology of American Folk Music as an 8LP cloth-bound box set. The label’s founder Eric Isaacson described it as “a game-changer”, responsible for changing America “more than maybe any other record ever made”. A story of obsession, bankruptcy and black magic built on a unprecedented collection of junk 78s, The Vinyl Factory’s Theo Leanse traces the making of an LP that shaped American music forever.

Words: Theo Leanse

Various Artists

The Anthology of American Folk Music

(Mississippi Records / Smithsonia Folkways, 2014 / 1952)

The Anthology of American Folk Music was compiled by Harry Smith for Moses Asch’s Folkways Records and released in 1952 at a retail price of $25. That’s $216 in today’s money (£130 in today’s sterling) and although you would have gotten three separate boxed-sets each with individual cover art containing two LPs and extensive liner notes for your bucks, this suggests that highly priced luxury ethnomusicological box-sets are nothing new, especially when you consider the fact that Asch and Smith hadn’t paid for the licenses.

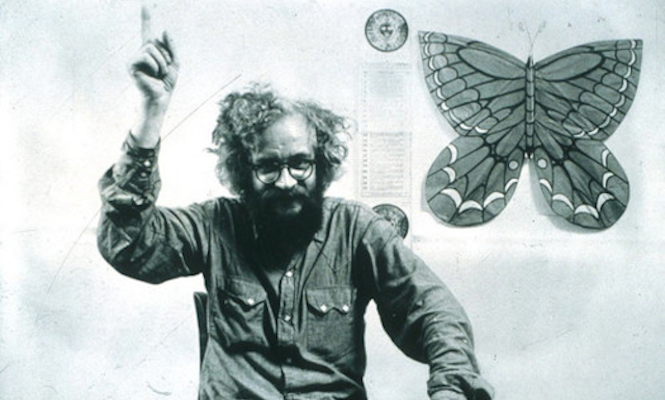

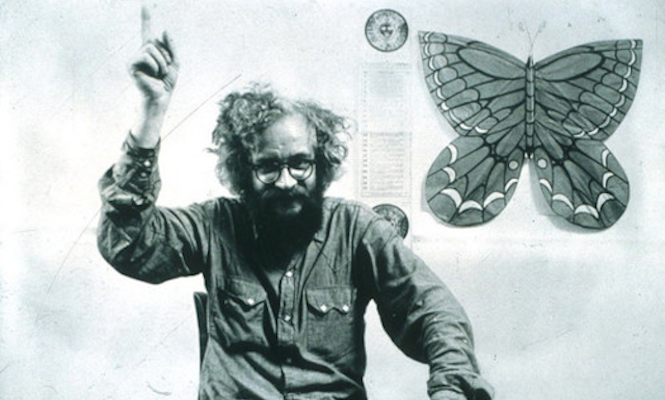

Harry Smith was an eccentric who collected obsessively – i.e. you can view his world-beating collection of string figures in a Brooklyn gallery, or his world-beating collection of Ukrainian dried and painted Easter eggs in a major central European museum. And there are other collections lost over the years: hawked, or abandoned in hotel rooms while Harry escaped unpaid rents, or stolen in revenge by angry neighbours at the Hotel Chelsea who broke in with fire axes after Harry’s long loud nights fuelled by amphetamines and the jazzy opera Rise and Fall of The City of Mahagonny by Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weil. He was an artist, a beat satellite, a maker of surreal animated films (some of which are now cult classics of early 70s cinema influential for the likes of Terry Gilliam – for a bit of a trip, see his boisterously occult masterpiece Heaven and Earth Magic). Born in ’23 in Portland, Oregon, he spent some time in Indian reservations with his schoolteacher mother, receiving shamanic initiation, and some time later moving to New York City to blow a filmmaking grant awarded to him by the Guggenheim.

In 1927 the American poet Carl Sandburg issued American Songbag, a literary collection of traditional American folk songs. Like the material on Harry’s later compilation, these songs drew across centuries and continents, often sharing focus with the Child Ballads – a landmark overview of traditional English and Scottish ballads drawn up in the late 19th Century by American scholar Frances James Child. Alan Lomax, the grand old man of folk field recordists, had detailed with Pete Seeger in the ’30s another map of the American folk music landscape – a definitive mimeographed list of songs to be preserved at the US Library of Congress’ Archive of American Folk Song. With these pointers and a healthy dose of compulsion, Harry Smith’s collection swelled to thousands of monophonic 78rpm records dated between the mid-’20s and the Great Depression, picked up as low-worth parochial trash from junk dealers.

But in the 1950s, when his money ran out, Harry tried to flog the collection’s best bits to New Yorker Moses Asch – and Asch suggested Harry sort out a compilation instead. Moe had collected popular records in Yiddish from an early age, setting up a small label for global ‘people’s music’ (Asch Records) that he quickly ran into the ground, declaring himself bankrupt and continuing shadowy business with a new label registered through his assistant Marian Distler. This label, Folkways, featuring titles like Japanese Buddhist Ritual, African Drums, Jamaican Cult Music etc., came to be synonymous with world ethnomusicology. But Moe also shaped and showcased the American folk revival of the 40s and 50s, releasing the companion album to Samuel Charter’s book-length country blues study The Country Blues and seminal folk works like ‘This Land Is Your Land’ by Woody Guthrie and ‘Goodnight Irene’ by Lead Belly (and even supporting enough down-and-out folk artists to eventually be figured as Arlen Gamble in the Coen brothers’ Inside Llewyn Davies).

Harry’s Anthology was released in three volumes – Ballads, Social Music and Songs. He planned a fourth, too – ‘Rhythmic Changes’ – but this only saw production in 2000 (and it’s pressed to its intended vinyl format for the very first time with this year’s editions from Mississippi Records). The cover-designs for the records took a detail from the illustrations to the work of 16th Century mystic Robert Fludd, and the colour scheme used to differentiate the volumes was an elemental coda drawn from the Enochian system of 16th Century occult prophet John Dee. Harry was serious about esoteric magic, eventually being ordained a bishop in the Gnostic Catholic Church of the notorious Aleister Crowley, and he evidently found some connection between the culture of American folk and the culture of the occult. So it’s possible the Anthology transmutes some buried Medieval magic. There’s certainly something extraordinary in these complaints about farming’s hardships, barn-dances, stern country hymns and rancorous lovelorn ballads.

Portraits courtesy of the Harry Smith Archives.

Read our in-depth interview with Mississippi Records’ Eric Isaacson here.