Published on

August 16, 2017

Category

Features

A musical tour of Amp Fiddler’s Motor City.

Growing up as one of five, Joseph “Amp” Fiddler was surrounded by music. Not just knee deep in the soul, jazz and psych collections of his siblings, he was totally deep in the rhythms of the city from a young age. Using his home collection as an archive, he spent his money on synths and rapidly made his way into the local scene.

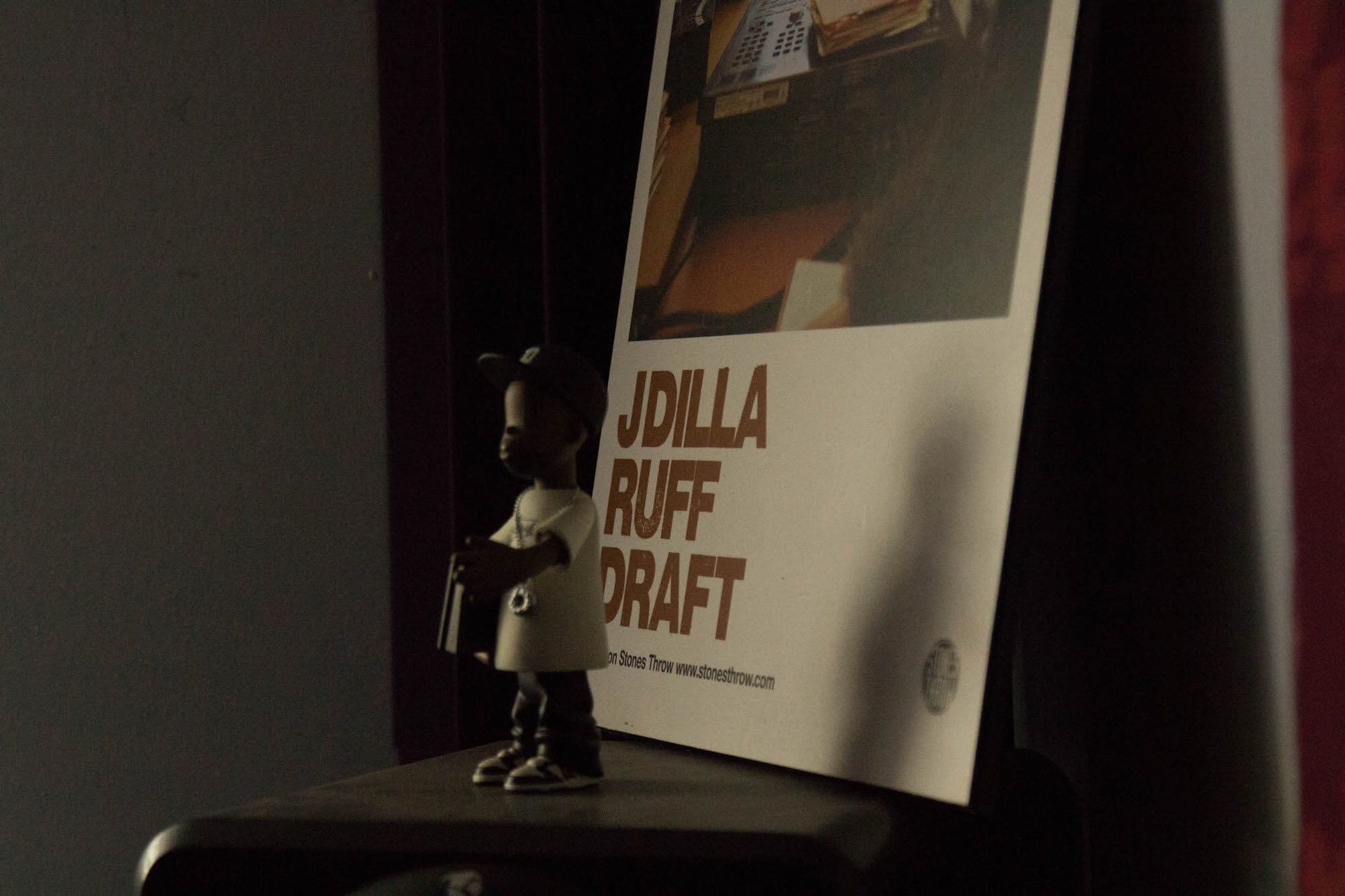

As a musician and producer, Amp Fiddler is the thread that ties funky Detroit together. From George Clinton’s P-Funk juggernaut to introducing J Dilla to the MPC one sunny afternoon, the stories he tells of the city are rooted in a sense of the everyday and a community that was blissfully unaware of its legacy. “I wish I had photographed the sessions,” he remembers of the basement where he taught a young James Yancey how to sample with an MPC. “In my mind I was just helping some kids because I thought they were talented.”

A generous musician, whose own music and his role in enabling those around him has given him an avuncular air, Amp Fiddler invited us into his Detroit home ahead of his performance at Dimensions to pick over some of those defining moments and the records that shaped him along the way.

Let’s start at the beginning what music did you grow up around?

I grew up around the music of a few different eras. My sister played a lot of music from Motown so I listened to a lot of Motown music. At that same time my sister under her was a hippy so I listened to Hendrix, Janis Joplin, The Moody Blues, The Beatles, all kind of rock and roll blues like Muddy Waters. Everything funky and rocky you know, Funkadelic… everything. My sister had all those records.

And at the same time my brother next to me was really into doo wop so he was listening to more Motown and vocal group stuff. My oldest brother was really into straight ahead jazz, so I listened to Lee Morgan, Horace Silver, Grant Green, everything on the jazz side. My dad was from the islands so we had calypso and soca in the house. My mum was from Virginia and she liked classical music. Those were all the records I was hearing as a kid. I never bought records as a kid, because why buy records? Buy records for what? I’ve got tons of records at my house, I’m not buying one, I’m buying a synthesizer.

As I grew older I started buying synthesizers as I started playing piano so I think Herbie Hancock would have been one of the first ones I bought. But still, why buy it? My brother has it in his collection so I’d just go look for it, he had all the records. There was a lot of new music coming out but I wasn’t really buying at that time.

You mention Herbie Hancock, what records were you drawn to in your family’s collection?

I liked his trio records and the straight ahead stuff he was doing at the time. I was such a fan and I was really trying to learn piano and jazz. If it wasn’t Herbie Hancock it was Thelonious Monk or Oscar Peterson who I really like. But I wasn’t always a big stickler on records like everybody was. It was just like, go through the records, find a record you love and play it. But I was so busy trying to play the piano that the records weren’t the focus, the piano was the focus! The records were to study.

As is reflected in your experience at home, Detroit is one of the few cities to play a formative role in multiple musical movements and scenes. What did that feel like from the inside of Detroit? You were talking about Motown versus…

The Philly sound. I mean I think it was something to be proud of because it put Detroit on the map of the world as one of the biggest music cities in the world. Not only would you see that and hear that music on the radio and see those records but the greatest thing was you could turn on the Ed Sullivan show at night and see some Motown act performing on there.

In terms of one act you were heavily involved with, it could be said that P-Funk’s relocation from New Jersey to Detroit played a role in developing their sound from doo-wop to psychedelic guitar funk. What was it like playing with George Clinton?

Well, it was total excitement. The first time I had to go on a tour I thought I was going to have rehearsals, but they gave me a cassette to learn the show and outlined everything. I was waiting for the rehearsal and I kept asking the band members when they rehearse and nobody gave me an answer. I finally asked Garry Shider, who was the leader, and he said “rehearsal is at the sound check when you get to the gig”. So it was always surprises and always interesting like that. I loved that about George’s spontaneity, letting you have the freedom to be you. My personality was all about where I wanted to be in that band and who I felt I was in that band.

That freedom also comes across in your later work as Mr.Fiddler, which connects the dots between black musical styles and eras.

My brother and I were Mr.Fiddler. We made that record in ’89 and up until now I still love the music of the ’30s and ’40s like Cab Calloway, Louis Jordan and Duke Ellington. And then the new stuff like Cameo, Parliament-Funkadelic and all the funky stuff. It’s like it was a combination of funk and forties, because I like the horns and all those other elements.

Is this also reflected in your own record collection? You spoke about listening to the music of your brothers and sisters at home but did you ever get into buying records yourself?

Here’s the thing, I’m the youngest of five so I have four generations, not including my mum and dad, who left records with me at my house when I moved here. So I had all my sisters’ records and all my brothers’ records. My oldest brother had a huge jazz collection, so I used to go to record shops with him and watch him buy records and pick records for him. I was just into playing the records I had, tonnes of them.

It’s why when Dilla came down here he had such a good time because the room was filled with records, crates everywhere. Twelve, thirteen, twenty times more records than this. But then the basement flooded and ruined the whole collection. And the ones that were any good we picked through, and I gave them to DJ Diz. So no, I really had no reason to buy records because we had so many here.

I want to get back to the Dilla thing in a minute but what does your record collection mean to you? You were talking about the family element of it.

It’s like a library, it’s like an archive. I’m really soured that I lost all the records that I had. I probably had three crates of my own personal stuff but it was more funk oriented and I did used to go out and buy funk records. And it meant everything because music is our sanctuary so regardless of how you feel you can always come home listen to records and feel better.

Is this still a lot of your family’s music in this collection here?

Yes. This is mostly my sister’s collection that I brought back from New York when she passed away so it means a lot. I’m sitting here listening to what she loved as well as what I love because her music was my music and I listened to records with her more than anyone else. I remember listening to this Roberta Flack record up in her room. It’s beautiful.

What records would you listen to when you weren’t working?

I might listen to Miles Davis, but I’m not a stickler on anything in particular. One thing I learned from Parliament-Funkadelic is that things never had to be so listed. Jimi Hendrix Experience is one of those – it’s a classic one that I remember listening to in my sister’s room.

You were talking about Dilla coming down here and seeing all the records…

It was a summer day like today. They were just getting out of school and they came over here because at the time I had old windows that flipped up which meant that if you were playing music loud everyone who walked by really heard it.

So Cricket, who was the kid who lived around the corner, first saw me out front and said, “Man I heard your music. You make music, we rap, can we come over?” and I said, “Come see me tomorrow, bring your friends with you and I’ll let you know if I can help you.” So they came, rapped, and said that they just needed music and somewhere to get their music done. And I asked them if they had anybody who could help make the beats and they said that James [Yancey aka J Dilla] could.

So I said to James, “Bring the music that you’ve made.” They played it for me and I was like, “How did you do this?” and he said he’d do a beat tape. And that’s how that worked out. He brought it over and the next day I took all the samples and I put them in the MPC and showed him how to use the MPC somewhat. I just produced the first demos for them with the loops that he had.

Did he ever sample any of your records?

He sampled a lot of records from here, definitely.

Any ones that stand out?

No I wish I could remember. It was so long ago. I wish I had photographed the sessions, the work, the whole thing back then. I knew how much of a talent he was, but I just didn’t think about photography at the time. I was doing other things, recording, getting on tour with George Clinton, it was just moving fast. In my mind I was just helping some kids because I thought they were talented.

What was it like to see his success?

You know it was amazing to see his success, because it’s amazing to see someone succeed when you’ve made your success. From helping someone learn the technology, helping someone learn the production, introducing someone to someone [Q tip] who puts them on, and they put hip-hop from Detroit on like he did. Because my thing was always to help to put Detroit hip-hop on the map and that’s a big accomplishment for the both of us I think.

How has Detroit changed over time, musically and socially?

It’s changing all the time. I mean we went from straight ahead swing jazz from the ’30s and ’40s to the ’50s. In the ’60s you had psychedelic and rock bands that came out of Detroit, from the MC5 to Ted Nugent to Parliament-Funkadelic. It was always evolving and I think most people in Detroit think about ways of continually innovating, so I still feel like Detroit is constantly evolving. From that we go into electronic music, techno and house and there’s still some reggae and other elements of Africa here.

And socially I hope that the community is coming together. Early on the city was so segregated and divided, black people didn’t know how to talk to white people and white people didn’t know how to talk to black people. The divide is 8 Mile. Where we are on 7 Mile, it’s mostly black and on 8 Mile it’s mostly a white community. They don’t like to cross. I think now that’s changing. I hope that people are becoming more sociable in the way they do things together that isn’t based so much on race.

The city is gentrifying, but I hope that the people moving in don’t disrespect the people who still live in Detroit as though they own it and owned it all the time. We should just be able to be here and be cool. That’s the way I see it.

Given that it’s constantly changing, where do you think Detroit heading musically now?

It’s all over the place now and I think it’s beautiful that people are becoming more and more successful and they are moving into the city. People like Jack White, who has this great place downtown. I think more smart people now are moving into the city and that’s where the music is going to evolve, when we just mix it up.

Someone was asking me in an interview about how I collaborate with so many different people and different levels of music and I think that’s the key to what makes things different. If I’m a soul singer and I collaborate with somebody that makes house music then OK, he’s doing something different over there because most soul singers stay in that one lane. So now I’m putting funk over to house music and collaborating with house guys or techno or even blues or even rock and roll you know? So I think that the more we start doing that the more innovative and different it’s going to get.

Amp Fiddler will perform at Dimensions Festival, 31st Aug-3rd September. More info & tickets here.