Brixton-based multi-instrumentalist and producer Wu-Lu tells us how he went from early Tony Hawk-influenced grunge to the turntablism of DJ Shadow and the genre-hopping foundations of his new record, S.U.F.O.S.

Throughout Wu-Lu’s latest work — which taps into racial injustice in Britain, black empowerment and self-exploration — it’s clear that South London is a passionate anchor for him. In what seems like no time, our conversation skips between tales and half-remembered accounts of his upbringing and the records that have shaped him, as he sips tea from a ’60s-style swivel chair copped from a local market.

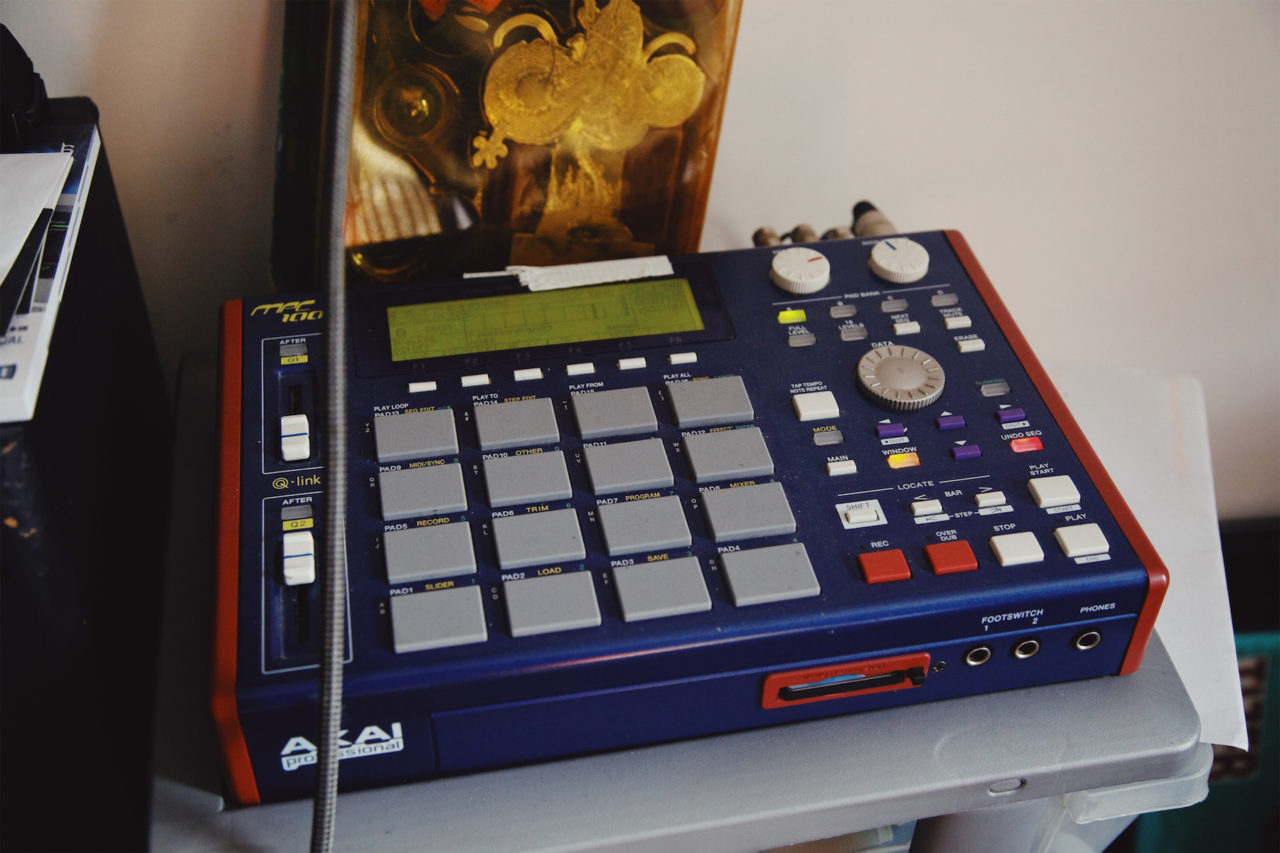

Although split between his house and the Hither Green studio where he spends most of his time, Wu-Lu punctuates stories of nascent DMZ raves at Brixton Mass and his involvement with local movements, DEM1S and Touching Bass, with peeks into a hearty collection of records. Nestled in the corner of his living room, the collection drifts from Italian soundtracks to D’Angelo, and skimming through them proves to be quite a trip.

Let’s start at the beginning. What are your earliest memories of music?

There was a lot of salsa, reggae, ska and a bit of indie in the house. My dad went on tour with a noughties indie band called The Blue Tones. My brother and I would go to the studio when they were recording and we’d get hyped because they had Tomb Raider. My mum always had salsa playing in the house because she was back and forth between London and Cuba. The odd R&B stuff too, like Lauryn Hill.

The first music to really grab me by the neck was probably Red Hot Chilli Peppers or Offspring – and to be honest, it was through skateboarding. Do you remember Spitfire, the skateboarding brand? I remember seeing an Offspring album in HMV with a front cover that looked like the Spitfire logo. The first Gorillaz album was also an influence, with all its weird Latin parts, hip-hop, garage, and it was all with cartoons.

I was probably around 10 or 11 when I got my first CD. It was from HMV in Brixton, where Body Shop is now. I saw Gorillaz and the first Slipknot album on the shelf and I bought the Slipknot one. But when I left I was like “dad, can I get the one with the cartoons on it,” but he was vex like, “why didn’t you say that to me in the shop, it was 2 for 1?”

I skated a little too, but the soundtrack for Tony Hawk Pro Skater 2 must go down as one of the best ever because it introduced me and so many of my friends to such a diverse range of music. Was that game and skateboarding influential?

Absolutely. Hector Plimmer says exactly the same thing. I remember my friend Remi had the demo that you’d get with the Playstation magazine, which only allowed you to play one of the levels and on a timer. It might have been THPS 2 where I got into liking the tunes, but never remembering what they were. Later on in life, I’d look back and remember that the game is what got me into Madlib. I knew the sound, but didn’t research it at the time.

Being a grunge kid at school, skateboarding went hand in hand with the music I was listening to. The Etnies, the big, fat tongue Vans — all of that. There’d be the odd summer jam at the Stockwell Park with a punk band. The local BMXers would get together a little stage, so it kinda felt like you were in the game.

So which records deepened your interest in music?

Well, when I was in school I remember this kid asking me what type of music I was into and I was just like, “I don’t know”. But he was like, “you’ve got to know what music you’re into”, so I just said drum and bass. Then I actually started listening to it and found Roni Size. This was when I was about 13 or 14 and used to hang around graffing. There was a shop called Red Eye Records and they used to sell bootlegs. I remember just pointing at one and it was this 16-bar jungle tune for about £5. I’ve got it somewhere in here. At the time, I didn’t have any decks, but I was just buying records so I could build up a collection.

I got Lady Sovereign’s record because it was red and my friend David bought me this beats and breaks record, Simon Harris’ Beats Breaks & Scratches Volume Eleven about a month later. Think it was either ‘Electro Shock’ or ‘Drum Culture’ that was essentially the amen break slowed down. We just used to sit there and get gassed off of increasing the pitch to jungle levels.

So, was that your entry point into jungle?

Yeah, definitely. Turntablism too.

Which brings us nicely onto your start as a DJ. How and when did you begin?

We must have been about 14 when my friend George had a pair of decks in his yard, mixing grime. After that I was just hooked. I didn’t actually get my own decks until maybe a year later. My dad ended up getting me a pair of cheap-ish ones for my birthday and from there it was on. I was buying records all the time, trying to find the cheap ones. Then I got into scratching having watched that film Scratch. After that I was sold.

Tell me about the effect of DJ Shadow’s Endtroducing…

It changed the game for me. I heard it in school and initially had it on CD, but when I had the chance to get it on vinyl, I had to. I heard ‘Midnight In A Perfect World’ on Scratch and they were interviewing DJ Shadow in the film, talking about the way he approached making music. I didn’t really know what he meant about a ‘break’, but in the film, him and Cut Chemist were finding sampled breaks and mixing the best parts. At the time, I thought he was playing everything which lead me to think that I should be doing the live thing.

I just like the idea of getting stuck in a basement somewhere, being a little hermit in a cave with my turntable and digging for treasure. Then I found out about RJD2 and that tune, ‘Work’, but initially I started digging for records in the same way that those guys were; turntablism tricks.

So how did you get from jungle and turntablism to dubstep?

I tried to get into Breakin’ Science, this D&B rave in Camden but I didn’t get in because I was underage and didn’t have my ID. Me and a friend went to another rave which happened to be Brixton Mass, thinking it would be another jungle rave.

Little did I know, I was at a really early DMZ. There were pretty much no drums and it was all whirry, alien sounds. Then Mala played and just dropped a reggae tune into some early, Coki-style weirdness. That was the beginning of it for me. Finding out about FWD, Tempa Records and Rusko. I found the wobble. Obviously, some of it went a bit crazy in later years but some of the early stuff, like Dubstep Allstars: Volume 2 by Youngsta and Mala’s ‘Blue Notez’ (on Dubstep Allstars: Volume 4), was so sick and new at the time.

I started my musical group, We Are Dubists, shortly after that and also started making music around that time.

So you were buying and making music simultaneously?

I was definitely trying to buy a record every couple of weeks. My dad had someone make him a computer and it had Reason on it, but he didn’t know what it was. I started making beats with my friend Remi – initially it was trip-hop. Me, Dan and Remi started my first dubstep group called Matted Sounds because we all had dreadlocks. We were just trying to work out the program because at the time, I wasn’t aware of YouTube or anything so I was just annoying friends to get tips. I was making dubstep right up until it shifted.

When it became brostep…

Yeah. But I can’t lie, I also got caught up in the wobble for a while. I was selective with the brostep.

How do you categorise your records?

There’s usually a form of categorisation, but after a set I’ll probably just bung the records into the empty spaces. You’ve got samples and breaks together, a mixture of jazz and stuff I wouldn’t necessarily play out. It gets a bit random as you get further down, but the 140-170 stuff stays tight and then you have the broken beat, garage and that sort of stuff. Loads of dub, reggae. Woah, I just found ‘Miracles’ — one of my favourite dubstep tunes.

Mala?

Yeah. I did also have a sick jungle remix of ‘Changes’ that Scratcha DVA played on Rinse FM one time. He did say who it was, but I wasn’t paying enough attention and just missed it. Classic pirate radio mistake.

Rookie. So, you box everything according to genres?

Yeah, dancier bits up top. I’ve also got some sealed stuff that I have two copies of or something like that.

Are there any records that are sealed because they’re sacred?

I’ve got a signed, limited run copy of Kendrick Lamar’s Untitled Unmastered. One day we’re gonna link and we’ll be signing our joint record for other people. Six degrees of separation. South London stretches far and wide.

Talking about South London, there’s obviously a lot going on down here. But beyond the well-documented jazz scene, what other movements are exciting you?

DEM1NS, Touching Bass. I feel like the South London jazz scene is actually just a part of the bigger South London scene. I guess it’s just turned the attention to everything else that’s happening here and created a wider lane for the young people playing live music. You look at the main heads in the scene and yeah, it’s jazzy, but it’s so much more. Improvised music is getting more attention, which is a good thing. For instance, Kwake [Bass] is improvising, using loads of buttons, boxes and drums to create songs on the fly. It’s almost like he’s doing a DJ Shadow tune live, transposing a beat maker mentality to make himself the one man spaceship.

Have you got any records that showcase your love for South London?

Yeah, it was one that you got me: [This Heat offshoot] Lifetones’ For A Reason. When you showed me that and gave me the backstory about the drummer [Julius Cornelius Samuel] being from Brixton, it flipped me. It sounded like they were making the music that I make, but without sampling. It sounded so current, even though it was made in 1982. What’s even crazier is that the drummer in This Heat, Charles Hayward, taught Kwake how to play drums. South London runs deep.

It changed me. It was the same as when I clocked Jon Bap. I think it all comes back to the tribal element of the drums and hypnotic guitar too. It brought me back to jungle, indie and hip-hop — all of the things that I love in one.

I hear that in your latest release, especially ‘Seven’.

Well, yeah. I was speaking to Shaun Sky the other day and he was telling me how much he loved the way Slum Village used to record. It was like they were just freestyling and then another day, they’d comb back through the recording and find bits that they liked. I did that with ‘Seven’. It gets its name from the time signature: ⅞ at the beginning and then it goes into 6/8.

So, what were you listening to when you were making S.U.F.O.S.?

Musically, there was a lot of grunge, this band called Family Fodder. A lot of Jimi Hendrix, Unknown Mortal Orchestra, My Bloody Valentine. I was also delving into a lot of Nirvana.

I wrote this song called ‘Soldiers Of A New Day’. It put me into the headspace that eventually birthed S.U.F.O.S. It looks at the concept of family, and how this relates to me, the people around me, and those that I’ve met along the way.

Interesting, loads of guitar-based music. A lot of people might not know that your twin brother is the brains behind indie-soul band, Childhood. Having a similarly inquisitive sibling must have its perks.

We weren’t always into the same music but there was a definite cross over when we were at my dad’s house and both heard Channel Orange separately. At the time I was listening to a lot of R&B and I thought it was so good: the songs, structure, everything. A week later, I heard it coming from Ben’s room and that’s when we started trading music. He’s the one who showed me Tame Impala.

Ahh, some brotherly love.

Yeah man. Alex G’s Rocket, Pastor TL Barrett, Little Ann — he showed me loads. My brother and I are definitely like musical yin and yang sometimes; we introduce each other to different shades of thought. Without him, I wouldn’t be the person I am today. He’s my best mate and someone that understands me in every way.

Wu-Lu’s S.U.F.O.S. is out now. Order a copy here.