Published on

October 6, 2017

Category

Features

A true NYC legend and resident DJ at the city’s most iconic clubs in the ’80s, Justin Strauss remembers the oft-mythologised scene that he shared with the likes of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, Larry Levan and many more.

It was a world where art, music and club culture grew hand-in-hand – where Keith Haring would dance to Larry Levan at Paradise Garage, where Thurston Moore rubbed shoulders with Jean-Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol at Mudd Club.

Resident DJ everywhere from Area to the Ritz, Tunnel to Mudd Cub, Justin Strauss lived through it all, channeling this no holds barred approach to creativity through his eclectic DJ sets. Launching a career that has seen him release a cult album on Island when he was just a teenager, notch hundreds of remixes, and amass one of the finest record collections in New York, Justin’s Mudd Club was the physical and spiritual centre of the city’s downtown underground.

With Jean-Michel Basquiat’s headline show Boom For Real now open at Barbican, and Justin on his way to London to perform alongside downtown alumni Kid Creole and Arto Lindsay, we visited him in his NYC home to hear a first hand account of daily life in the rundown, beat-up, beautiful, creative and liberated melange of early ’80s New York City.

You’re about as much a New Yorker as they come. Has your experience of the city always been tied to music too?

Yeah, I was born in Brooklyn and have called New York my home forever. Ever since I was a little kid I was drawn to music. My dad was very into music, audio gear and equipment, and he was always playing music around the house. And then when I was very young I saw The Beatles on Ed Sullivan and from that day on, that’s all I ever wanted to do. It changed my life, it informed my life, and gave me a passion that I’ve followed ever since.

So were you one of those kids who’d save up his pocket money to buy 7″s?

I remember literally saving up my change, and my dad taking me to the record store. We would go record shopping and I bought my first Beatles single with my own money. I still have it and I’ve never stopped going to record stores since. At that time pop music was very varied, you had the British stuff, you had the soul stuff, you had James Brown, and all these things were influencing me.

You were also playing in a band too, right?

Yeah, I got into a band in high school. I was into Bowie, T-Rex, all the glam stuff, and we had this band called Milk ‘N’ Cookies with a few high school friends. We all loved Sparks, so we we sent our demo tapes to Sparks’ and to David Bowie’s managers, because they were the two people that we loved. We got a reply from Bowie’s manager saying, “keep up the good work, but we’re too busy.” Then we got a letter from Sparks’ managers saying, “we love you, we want to work with you, and Island records wants to sign you.” So we were sent to England where our album was produced by Muff Winwood, and it was going to be the biggest thing since sliced bread. This and that happened, but it didn’t really turn out that way. The record became a big cult thing though, and was reissued a few years ago by Captured Tracks.

Was the step towards DJing an obvious one for you?

Well, the band got me involved in the music business, and that went on for a while, until we broke up and I moved out to LA. But, you know New York is in my blood. I was really missing family and friends, and I wanted to come home. I was talking to an old girlfriend of mine, and she said to me, “there’s this place in New York that’s just opened called the Mudd Club, you should come check it out and DJ there.” And I said, “Well, I’ve never DJed,” and she said, “But you’ve got all the records!” I went there and immediately felt very at home.

Although you were primarily playing in bands, did you have much experience of the club scene in the city?

When I was like sixteen we would sneak into Studio 54 and those places. I went to some of those really amazing clubs back then, but Mudd Club was completely different. I got to play one night, and the owner of the club Steve Mass asked me if I’d like to work there on Thursday nights, so that’s what I did.

So you had the records, but hadn’t considered DJing?

DJing wasn’t like it is today where it’s the number one job that people want to do. Nobody really thought about being a DJ back then, it was still very underground. I was in this band and I was thinking that would be the path to take.

But in addition to buying all kinds of British stuff, I also bought all the early disco 12″s, Walter Gibbons mixes and so on. I had a very open mind, and I was never very genre obsessed. So DJing wasn’t ever really in my mind until it was presented to me. I didn’t really know about beat matching or anything like that. At the Mudd Club it was just very rinky-dink – they didn’t even have 1200s – and you just played one record after the other and they kind of made sense.

This eclecticism seems reflected in the labels and shops that are prominently remembered from that time like Ze and 99 Records…

Yeah, 99 Records is where I would buy a lot of records. And then I’d go to Vinyl Mania and buy all the imports and the dance records. Sleeping Bag with Mantronix productions, and we were all friends. I ended up getting into remixing and I’ve remixed hundreds of records.

Yes, let’s talk about that. Like DJing, remixes were far from common place at that time…

As I became the resident DJ at some really important clubs in New York like the Ritz, and then Area, Tunnel, the Limelight, record labels would bring me all these records. Remixes were still a small thing and my heroes were Shep Pettibone, Larry Levan, Francois Kevorkian and Water Gibbons. It really intrigued me and it was something I wanted to do.

Labels would rely on club DJs to break their records, so one day I said, “hey this is cool but I think I could do something better with it.” So I got my first remix and it did quite well and started getting more and more. I’ve remixed everyone from 808 State to Luther Vandross to Skinny Puppy.

It doesn’t seem like a coincidence that remix culture emerged from a scene where art was taking historical pieces or collage or sampling, it all comes from working with pre-existent media and finding a new expression for it…

Yeah, that’s very true. As a remixer I always approach it from the point of view of what would I like to play. I’ve had some records that I loved that were really hard to change. I was asked to remix Luther Vandross ‘Never Too Much’ and it’s like “oh my god…”

It packs such a punch already…

And that was quite an interesting experience, because I didn’t know that when I booked the studio to do that mix that Luther Vandross was in the studio next door, working on Whitney Houston or something. He came in and heard the remix I was working on, and he asked me if he could sing on it because he loved it. So we set up a mic and he added all these vocals, it was insane.

Going back to your work as a DJ, perhaps buying records without the dancefloor in mind helped form that very open style of music you played?

It definitely wasn’t on my mind, and when I went to the Mudd Club I saw that people were dancing to music from a very broad spectrum. The Mudd Club gained notoriety because it was the anti-Studio 54. Disco was getting a bad rap at that time, it became over commercialised and there was a lot of crap around. Here, people would dance to David Bowie, Loose Joints, Trouble Funk or lots of different kinds of things and it somehow all made sense.

I think it was just a completely different time, particularly here in New York in the downtown scene, where people like Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring and all these amazing people that I met and came into contact with were just hanging out at this one place.

And that’s a testament to how important a venue or a meeting point can be in the coalescence of a scene like that. Mudd Club became the home to all these convergent art forms…

It encouraged them too. I got a job there and I’d never DJed before in my life. Keith Haring and Jean-Michel did work and presented things in that space long before anyone cared about them. New York was in a bad place, it was run down and the rents were low, so someone like Keith Haring could come and get a little studio on Broome Street for $200 a month and make work.

It seems like part of the mythology around that period is also connected to how rundown the city was, and how creativity could flourish in adversity. Was it not also a really difficult time to actually live in the city?

Yeah, definitely. The neighbourhoods that today are considered chic were places that you just wouldn’t go because you would get killed. Drugs were rampant, crime was rampant, the whole scene in New York was very grim in a lot of ways. But that just fed the creativity of artists like Jean-Michael and Keith, as well as musicians like Arto Lindsay and the whole no wave scene. That also had a big influence on the Mudd Club, who all played there. It incubated a lot of stuff.

From the outside it seems like there was a strong sense of community too which helped bind things together…

Yeah, everybody was helping out each other and there was a lot of collaboration. The music and the art world were so interconnected – the artists, the DJs and the musicians were all hanging out and inspiring each other. I think that’s what really made this time so culturally important.

Do you think that was partly because people had a more open mind to other disciplines or it was just less formalised?

It wasn’t formalised, and no-one thought much of it. No-one would have thought that at one point Jean-Michel would have held the record for the most expensive painting by an American artist at auction. It’s just insane to think that, because back in the day he was just painting up some box in the Mudd Club or on the street. It was just people doing what they love, not thinking of anything else. Maybe just selling a piece to survive or getting money to live and pay the rent. It was the struggle!

But you first crossed paths with Jean-Michel at Mudd Club while you were DJing there?

Yeah, we were friendly, but he was quite a shy guy. I became good friends with Keith Haring and through Keith I met Jean-Michel and the others. Jean-Michel was always a little stand-offish, not as outgoing perhaps, but he was seeing this girl for a while, Suzanne Mallouk, who I knew really well. I’d see him at the Mudd Club and then at this club Area, which was like a club-come-art project that would change its decor every 6 weeks, and was totally unrecognisable. It was one of the most unbelievable clubs of all time, and I was the DJ there on Saturday nights so everybody was just hanging out in these places.

So you’d just bump into people out and about?

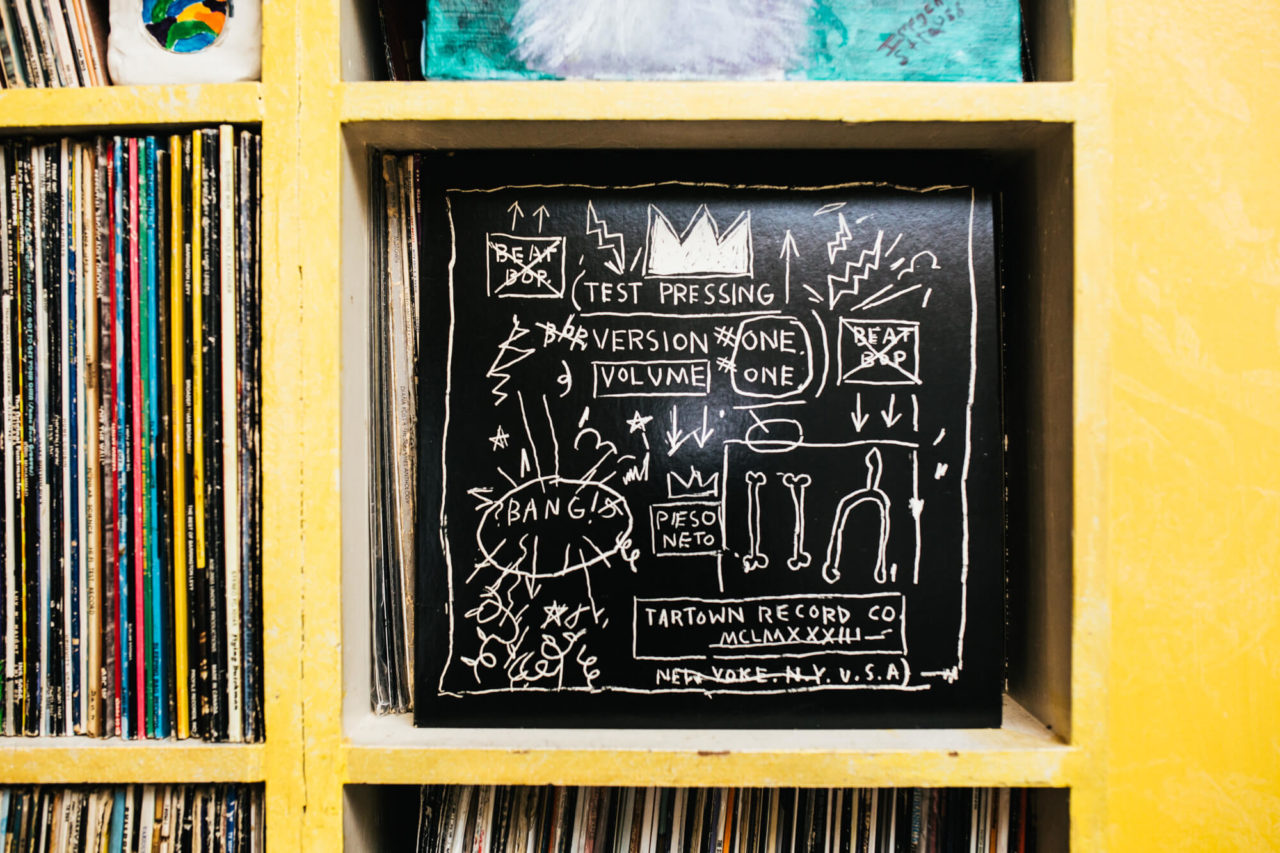

Yeah. For example, going to the Paradise Garage really changed my whole idea of what a DJ is, and Keith Haring was always at the Garage. There was this whole connection with that, and Jean-Michel with the hip-hop world. He did that Rammellzee record Beat-Bop, which is now a modern day classic. At that time I was working at Area, and he would DJ there in the back bar room playing jazz and dub. Beat-Bop is still one of my favourite records.

That said, it seems like he was propelled pretty quickly into the centre of the more established art scene too?

Yeah, a Basquiat opening or a Keith Haring opening was quite an event, and there you started having the more established art world coming through. You’d have Bowie hanging out at the Mudd Club, Mick Jagger, Andy Warhol was always there. Andy was the bridge between the uptown old guard and the new kids. He could be friends with both sides and really connected everyone together. When I was a kid I was in love with Andy Warhol. I saved up $800 and bought an Andy Warhol “Mao” when I was 16 years old!

Basquiat also brought a more punky asethetic into the rarified art world…

Yeah, he changed the way people look at things. What people would just consider sketches or doodling now had meaning and substance, and Andy saw that very early on in his work. Obviously a lot of Jean Michel’s work has a lot of important messages – political issues, racial issues, economic issues and people really gravitated to it, because it was also very appealing to look at. There was also so much of it, it was astounding to see how much work these guys did at that time.

Both Keith and Jean-Michel were starting out doing stuff on the street, on the subways or wherever they could find a place to exhibit their work and what happened to it after that is pretty amazing.

Was there also a hedonistic, slightly self-destructive edge to it all?

Yeah, the amount of money that came into their lives in a very short time was hard to deal with, I guess. All of a sudden you’d see Jean-Michel dressing in Armani suits and he’d look amazing. There was so much money around, he didn’t have to worry about it any more. And there were things that led him down a path of destruction.

It must have been quite a shock when he died at such a young age?

I mean, I don’t know if it was shock, because anyone who had been around the scene knew that this was part of what was going on with some people. I feel really lucky because I never got into drugs. I’ve never actually done any drugs and I’ve been around them my whole life. It sounds corny, but it was true, music was the thing that saved me so many times in my life and that was all I needed. I would go to Paradise Garage on a Saturday night and my mind would be blown.

It was very sad obviously, because you think of what else Jean-Michel could have become. He did something and he changed the world and not many people can say that. It’s incredible to think how young he was when he passed away, given how much work he made.

With your open-minded approach to the dancefloor, are you able to put your finger on a few records that were particularly formative or important?

Yes. At the Mudd Club we were really just flying by the seat of our pants. Steve Mass had some very crazy ideas. For example, I wasn’t working that night, but he told the other DJ to play the same record all night long. And people would come up to the DJ and be like, “why don’t you play something different!?” It was just like his art project, and it didn’t matter. That was it!

Personally, I was being influenced by things I heard at the Garage, but I was also playing at some of the more new wave clubs that were happening at the time, so my sound was bridging a lot of that together. To me it was natural and I didn’t hear anything different about playing a Loose Joints record, and then playing a Depeche Mode record. It all worked in my head.

I remember walking into the Garage for the first time and I didn’t know most of the stuff that Larry was playing and I was like, “what is this, what is this…?” I got to be friends with him and he just turned me on to so much music and that was a great thing as well.

In one recent Crate Diggers interview, Eamon Harkin from Mister Saturday Night cites you as a massive influence, so it’s really nice to see that continuity in NYC from Larry to you to him and beyond…

There’s a synergy I guess. Last summer I played with Optimo at Sub Club for the first time, even though we’ve been friends for a while, and the next night we played together at the Robert Johnson and it was great. At the end of the night, Keith McIvor played a remix I did of Skinny Puppy as the last song. And he told me that he played that song in his first ever DJ set! So it was a really great feeling because I love them and what they do. It was a great feeling to know that something I did was in his first DJ set and had inspired him. As corny as it might sound music is my drug, and it’s what has inspired me and influenced my life in every possible way.

Photos by James Hartley.