Published on

November 9, 2018

Category

Features

How the near-mythical live recording was saved from obscurity.

In early 2013, we spoke to DJ and producer Amir Abdullah about his new label 180 Proof, which is dedicated to breathing new life into the lost catalogue of independent Detroit label Strata Records.

Founded by pianist Kenny Cox in 1969, Strata was one of a handful of black-owned independent labels that emerged in the early ’70s to put the power and control back into the hands of musicians. It may have released fewer than ten records in its lifetime, but Strata’s role within the community ran deep. Founded off the back of the riots of 1967 and 1968, Strata began by running food drives and workshops for local people, advocating for jazz musicians frozen out when Motown headed west.

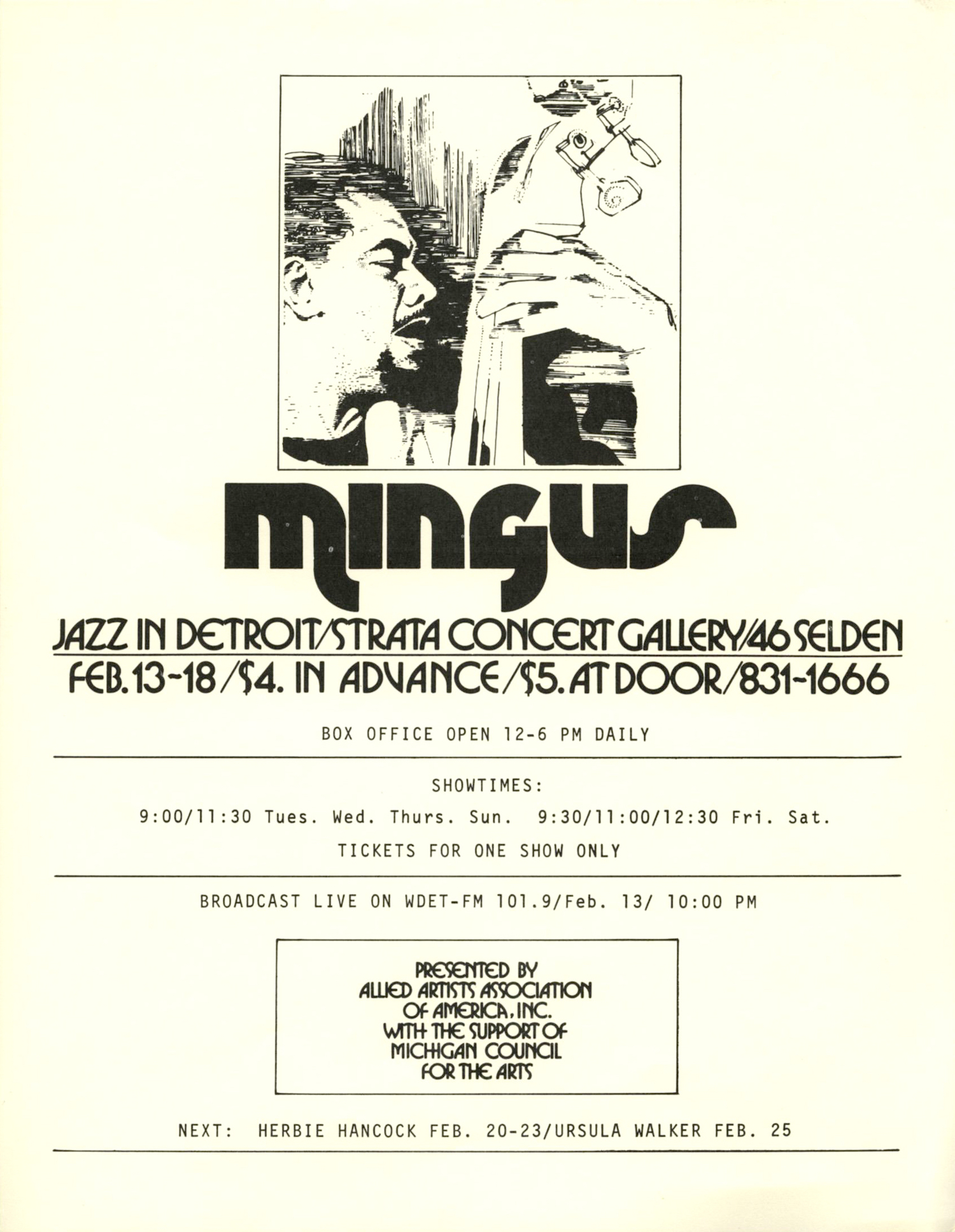

A popular figure on the jazz circuit, Cox would also leverage his influence by bringing heavyweights to the label’s gallery space at 46 Selden, where they would play for a fraction of their going rates. Performances would be recorded live and broadcast on local radio station WDET for the enjoyment of those who were either unable to attend or pay for a ticket to the show.

Back in 2013, Abdullah told us that he had it on good authority that somewhere among the piles of unlabelled master tapes, multi-tracks and live recordings he’d acquired was original material by the likes of Charles Mingus and Herbie Hancock, recorded at these concerts. The programme for early 1973 was tantalising enough: Charles Mingus, Keith Jarrett, Herbie Hancock and others all appearing within weeks of one another.

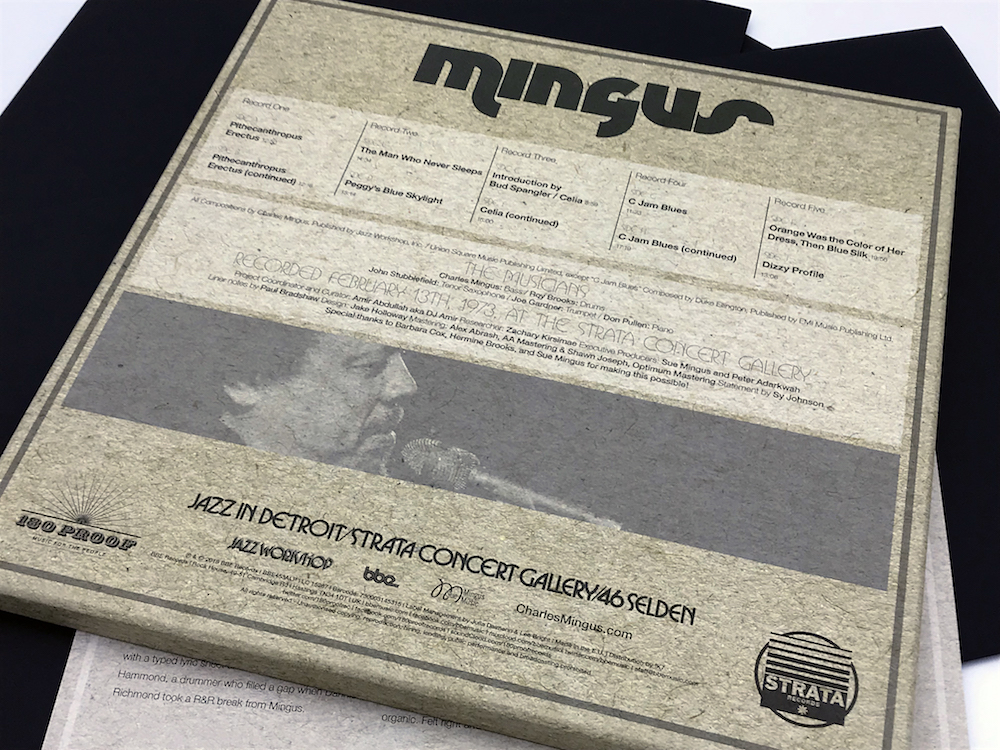

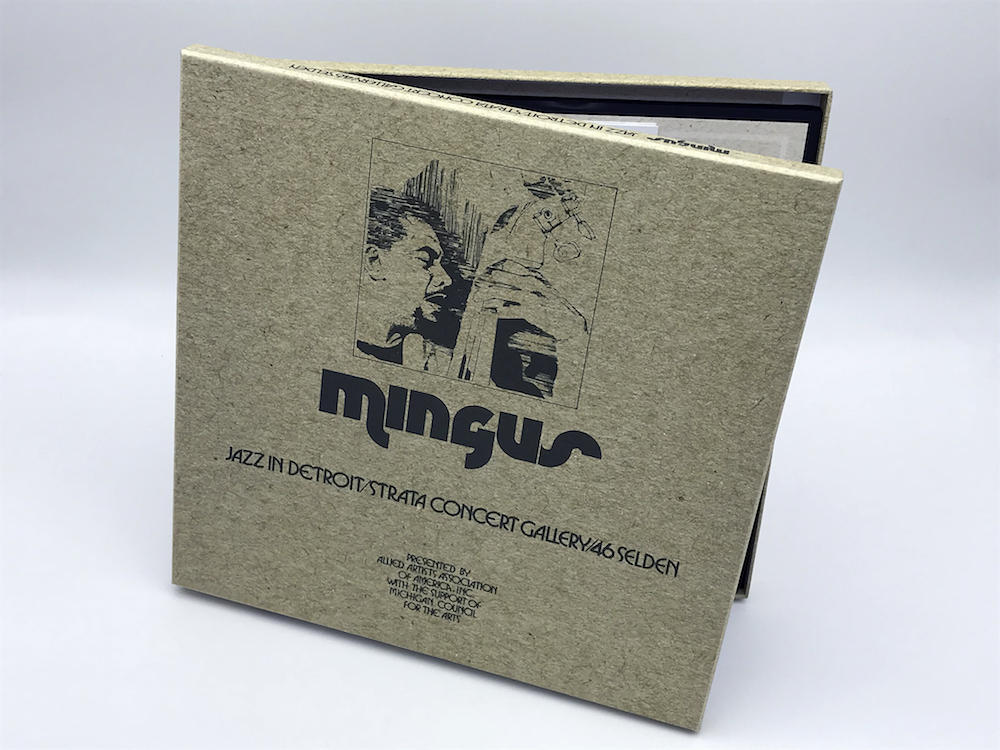

Five years on from that interview, Abdullah has finally overseen the release of some of this material in the form of Jazz In Detroit, a 5xLP recording of Charles Mingus, released in partnership with BBE. Abdullah tells us about how it came to be.

This story begins in a fortuitous manner, doesn’t it? You received an email from Cox’s widow and Strata owner Barabra Cox…

Yeah, she just said, “hey, my friend Hermine Brooks has the Charles Mingus Strata concert in her possession and I’ve told her to give it to you to put it out, do you want to do that?” I was like, hell yeah! Why wouldn’t I want to do that? I didn’t even know what songs were on it!

How did Hermine Brooks come into possession of the tapes?

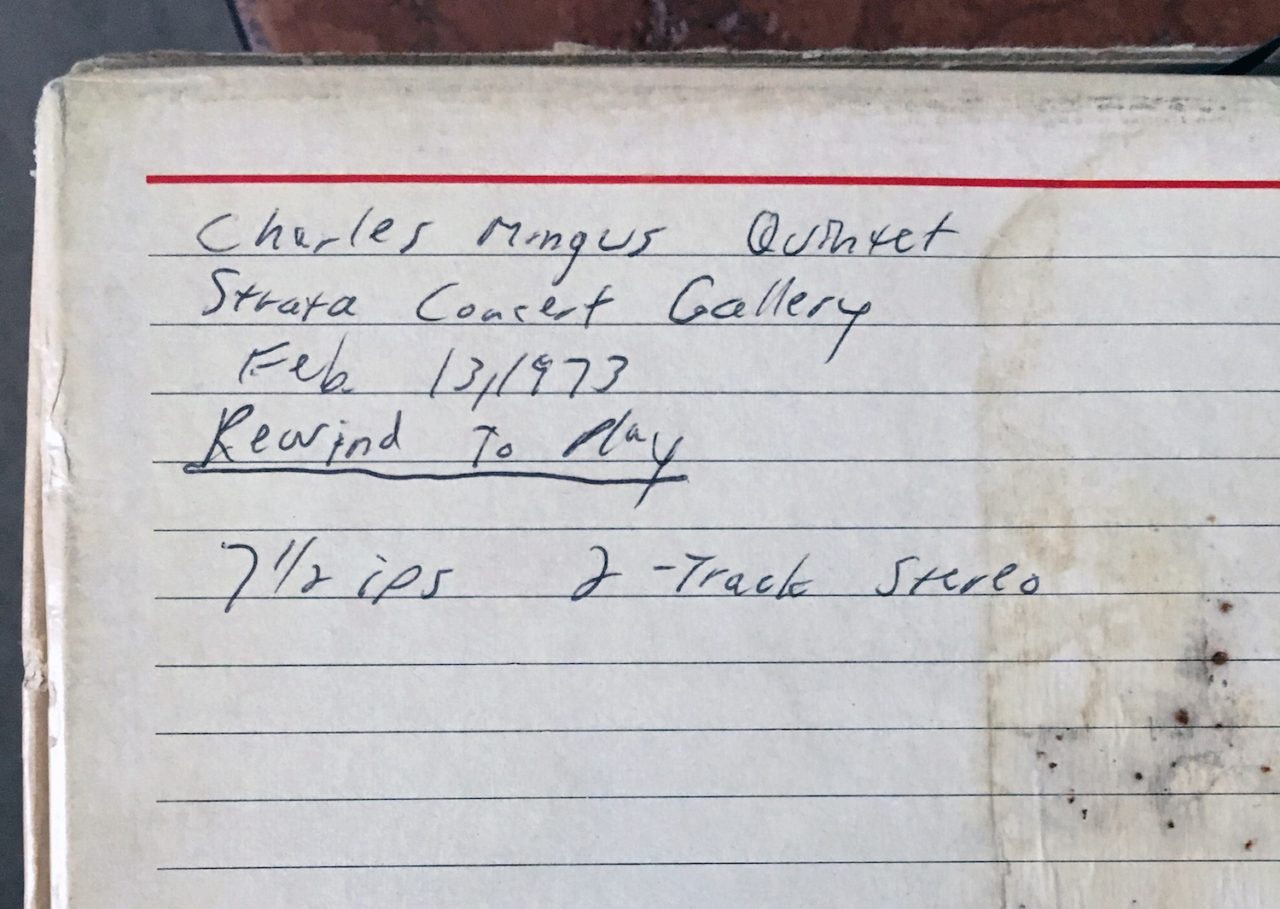

Her husband was Roy Brooks who played drums with Mingus. I assume he acquired a copy the night of the concert. I couldn’t wait to hear them. No one had heard it unless you were there on that night in 1973. It’s like 4 and a half hours of music!

That must have been extraordinarily exciting.

Yeah, and there wasn’t only music on there, you could also hear the audience, Mingus talking to the band, the band talking to Mingus. On top of that there was a 15-minute interview with Roy Brooks, the drummer, just in the middle of the thing! He’s talking about the politics of jazz and Keith Jarrett. I don’t remember exactly, but I think they say Jarrett had been dropped by a label and they go on about how it’s a sad thing and that people are trying to whitewash jazz. This is ’73 and people are going on about this.

I guess that feeds into the bigger question of representation and creative control that Strata was advocating for. What about the music itself?

The whole thing is special, but there are two very special songs. I think this is the earliest known recording of ‘Noddin’ Ya Head Blues’, and ‘Dizzy Profile’ has never been on record before. It definitely has a lot of the band communicating and one guy in the audience is clearly drunk! He calls Charles Mingus, Chuck: “Chuck man, you’re the greatest!” He got really comfortable by calling him Chuck. I’m not sure if Mingus liked that or not, but that’s how intimate and small the concert gallery was. You could reach out and touch these people easily. It makes for a special part of the recording.

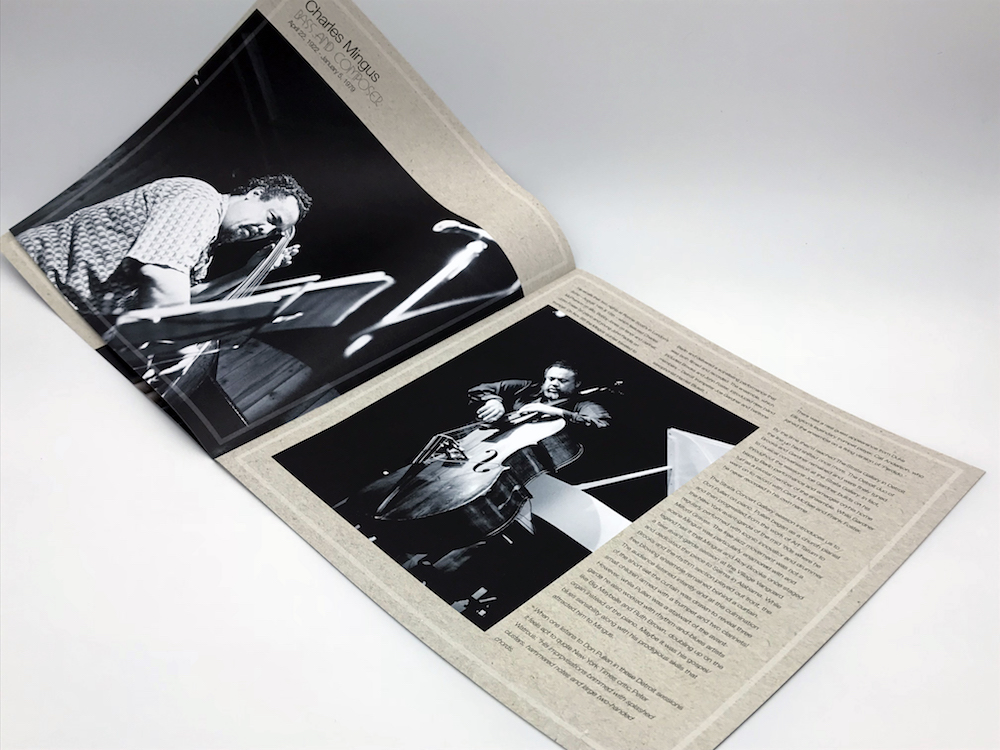

Another great thing is that John Stubblefield who plays the tenor sax on the recording was only with Mingus for like six months – they got into a big disagreement and John left the group. This is the only recording of them together. Later on, after Mingus passed away, Sue Mingus invited him to become part of the Mingus Big Band and he was the only one who had played with Mingus. It added a great quality and means he could mentor the others in the group. There are a lot of special things about this recording. It is a historical document, both visually and aurally.

You’re right, it adds pieces to the story that you wouldn’t necessarily hear on a more polished recording.

Exactly. People have already asked me, “Is the sound quality good? Does it sound OK?” First of all, it’s a live recording and we’re a small operation. We don’t have a huge budget like Sony or Universal where we can go in and really just desensitise the recording until it is so sterile. I don’t want that. You pick up some of the microphone feedback on some of the recordings, and I think it adds a special quality to it because it is real. You are hearing something from history and sometimes history is not pretty. History is sometimes not the cleanest thing in the world, but it is history and we all need to learn from or enjoy it.

I wanted to do this right, so part of the process was finding out that Mingus’s widow, Sue Mingus, was still alive. I did a Google search, found the website and called a few times and one time she picked up. She told me to send her the music. I didn’t want to spend any money mastering this until we got her permission. I’m glad I did that because she is super psyched and she contributed notes to the project.

When we first spoke about the Strata/180 Proof project a few years ago, you mentioned that it was Kenny’s connection to these musicians that made the difference – that they would visit the space and play under more informal circumstances.

Exactly. I’m sure that more well-known jazz clubs were wondering how they got Mingus, Herbie [Hancock] and Ornette Coleman, to come to this small, intimate gallery. But they had a vision and were doing something that was really good for the city of Detroit.

Right – it was bigger than a musical enterprise.

In ’67 and ’68, Detroit had two riots which really devastated the city, and which they are still really affected by. You had all these turbulent things going on in the early ’70s, with Nixon and Vietnam, and it was just a cauldron of chaos. Throughout that chaos, you had places like the Strata gallery and Tribe Records in Detroit who were trying to make some sense of the chaos and give people a relief through art, music and culture. What better way to do it if you have a relationship with the likes of Charles Mingus? I’m sure it wasn’t a great money maker for him, but he was able to come and do it and put on a great show.

They also went further and broadcast these shows on local radio, right?

Yeah, you’ll hear it on the recording. Robert “Bud” Spangler says, “this is brought to you live by WDET, Detroit and also by the Michigan Council for the Arts. WDET probably has all the recordings in its possession too. Five dollars probably wasn’t that much money to go and see Mingus or Herbie. If you were going to a big stadium at the time, you were probably playing $20-$30 or more to see them.

Unfortunately, it wasn’t a packed house, because you can hear them say, “although we don’t have lot of people down here, we’re encouraging people to come.” You’d think that as it’s Mingus, people would be there. Despite all of that, they gave an amazing show.

Photo by Hans Kumpf

How has the process of releasing it been in comparison with other releases you’ve put out?

It’s taken me about a year to get it to this point. Although the quality of the masters was relatively good, it took over 7 months to get it to what it sounds like. There was definitely a bit of distortion and microphone feedback. Also, on some songs, whoever was recording it must have accidentally pressed ‘stop’, so bits were choppy and we had to figure out how to get around that. Most of the songs were 20-25 minutes long, with a few closer to 30, so for vinyl, you’ve got to figure out how to split up songs that were never made to be split because they’re just one song, because you can’t do 30 minutes on a side.

We also had to do a lot of research. It was extremely hard to get photos of everyone in the band. I didn’t think it would be that hard. We almost had to go without a photo of John Stubblefield before someone came to us with one at the last second. Also with Joe Gardner, the reason we only have his death [date] is because we couldn’t find any information about his birthday. Sue corrected us on a lot of things, which I’m glad she was able to do. I had to rely on the people who were there and who knew Mingus the most. It was quite a challenge.

Have you made any curatorial decisions on what goes into the release?

The whole performance is only available digitally. The vinyl is only 5xLPs. There are a bunch of alternate takes that also had to go onto the digital release. The vinyl doesn’t have the Roy Brooks interview because that’s about 38-minutes long.

You touched on it a few times implicitly, but there are more Strata Gallery concert recordings out there. What’s next?

I’m trying to secure the Herbie Hancock concert, and I’d love to hear the Weather Report show. Then there’s Keith Jarrett, Elvin Jones, and Ornette Coleman. It had to be a regular thing to afford to keep a roof over that place.

Charles Mingus’ Jazz in Detroit / Strata Concert Gallery / 46 Selden is out now via Strata / 180 Proof / BBE Records. Order a copy here.