Published on

February 6, 2019

Category

Features

The instrument Vangelis once called “the greatest synthesiser ever made.”

Introduced between 1976 and 1977, it wasn’t until 1982, shortly after its production had ceased, that Yamaha’s flagship analogue polysynth, the CS-80, cemented its place in the history of popular music.

The story of this remarkable instrument begins with its predecessor: Yamaha’s famed GX-1. Conceived in the early seventies and released to the public in 1975, the GX-1 was a picture of musical indulgence. Weighing 387kg, it contained three keyboards, 25 bass pedals, 36 ‘tone generators’ (Yamaha’s catch all term for an oscillator and each attenuating component placed along its signal path, mounted upon the same circuit board) and came with a $60,000 price tag. Despite being one of the most capable and expressive synthesisers around, its weight, complexity and price obstructed its commercial viability. The next logical step was to replicate its qualities within a streamlined, more affordable model.

So the CS-80 came to be. Foremost among its features was 8-voice polyphony, allowing the player to produce eight notes simultaneously — each dual-toned thanks to the CS-80’s 16 tone generators. Prior to this, musicians had used monophonic synths, such as the Minimoog and ARP odyssey to compose single note sequences (take Herbie Hancock’s ‘Chameleon’ or Jan Hammer’s ‘Earth (Still Our Only Home)’ as examples). By 1975, synths like the Oberheim FVS-1 were offering 4-voice polyphony, but even that wouldn’t have realised the rich chromatic chords associated with the music of Herbie Hancock or Vangelis. The CS-80 represented a huge step forward.

On top of those tonal capabilities, the CS-80 enabled unprecedented expressive control, which, unlike the patch systems of earlier modular synths, were friendly and intuitive. Take the tactile ribbon controller for example: a vertical black bar you would run your finger along to achieve polyphonic glissandos (or smooth glides between multiple notes). Yamaha claimed that the CS-80 had the touch of a traditional acoustic piano, with a weighted keyboard and controls to replicate the sustain and sostenuto pedals. But it also had polyphonic aftertouch, meaning that if you held a chord and varied the pressure with your fingers as you held the notes, the sound would respond to the changes in pressure.

However, as with the majority of analogue synths, the CS-80 still had some significant flaws. Although trimmed down, it still weighed more than the average human being. It was also extremely sensitive to temperature and humidity, both of which could wreak havoc on the oscillators. Another potential drawback was the lack of digital memory. Its analogue patch memory was out of step with the digital alternatives that followed soon after on synthesisers like the Prophet 5.

Despite its temperamental nature, the CS-80 was capable of extraordinary sonic feats. Its ring modulator endeared it to the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, while the timbre and performance controls led Vangelis to call it “the greatest synthesiser ever made.” Perhaps John Carpenter collaborator Dan Wyman best summarised its qualities, when in 1979 he stated, “The CS-80 is a step ahead in keyboard control, and a generation behind in digital control.”

Here are ten albums that were shaped by, and show off the remarkable qualities of, this great ’70s synthesiser.

Brian Eno

Before And After Science

(Mercury, 1977)

The CS-80 arrived on UK shores during the period in which Eno was making Music for Films and working on Bowie’s seminal Berlin albums. Sessions for Before and After Science had started approximately 18 months earlier and he was revisiting the project in between commitments. The processes that shaped the album were typically experimental. Eno implemented techniques such as reduction — which involved creating a multilayered arrangements before stripping away tracks deemed non-essential — and worked with an array of German and British musicians. He used the CS-80 on the first three tracks of the album’s B-side: ‘Here He Comes’, ‘Julie With’ and ‘By This River’, bringing a wash of colour to songs that were creatively austere and at odds with rock convention. ‘By This River’ and ‘Julie With’ are particularly fine examples, with keyboards such as the CS-80 shining in place of acoustic drums and electric guitar.

Wire

154

(Mercury, 1979)

Having produced Wire’s astonishing debut Pink Flag, Mike Thorne was purportedly given an unusual ultimatum by the band: “Unless you play those keyboards and synthesisers we’re going to get that Brian Eno in!” Thorne didn’t need telling twice and on subsequent albums Chairs Missing and 154, he brought sonic depth to Wire’s evolving art punk sound. The CS-80 is a vital component of 154, and although not drenched in reverb, the character of the patches used on ‘I Should Have Known Better’, ‘The 15th’ and ‘On Returning’ add depth and unsettling character from beneath the rhythm instruments and vocals. Thorne has said that he treated synth parts like colour for the arrangements and, during what were tense sessions, wasn’t too forthcoming with creative ideas. Nevertheless, his CS-80 usage is vital to the mood of this classic post-punk album.

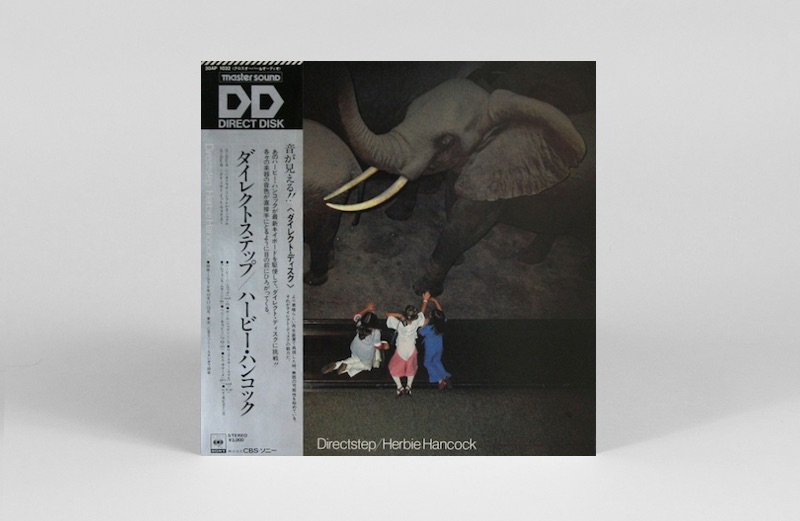

Herbie Hancock

Directstep

(CBS/Sony, 1979)

Herbie Hancock has never been afraid of experimenting with electronics. He first made used of a synthesiser in 1973, on his jazz funk classic Headhunters, and has since wilfully adopted new technologies into his sound. During the late ’70s and early ’80s, he created rich compositions, in some cases utilising upwards of ten keyboard instruments per recording. Any number of his releases from the period – his album with Kimiko Kasai, Mr Hands or Magic Window – would have been worthy of mention here, but it’s this Japanese-only release that was the strongest. It begins with a rework of one of Hancock’s most famous tracks, ‘Butterfly’. While the recording is remarkably clear, it’s hard to single out Hancock’s CS-80 lines, as both he and second keys player, Webster Lewis, used so many keyboards on the record. However, seeing Hancock pictured with the CS-80 in the gatefold sleeve and hearing its characteristically ethereal swells throughout, it’s fair to say the synth made its mark on this recording.

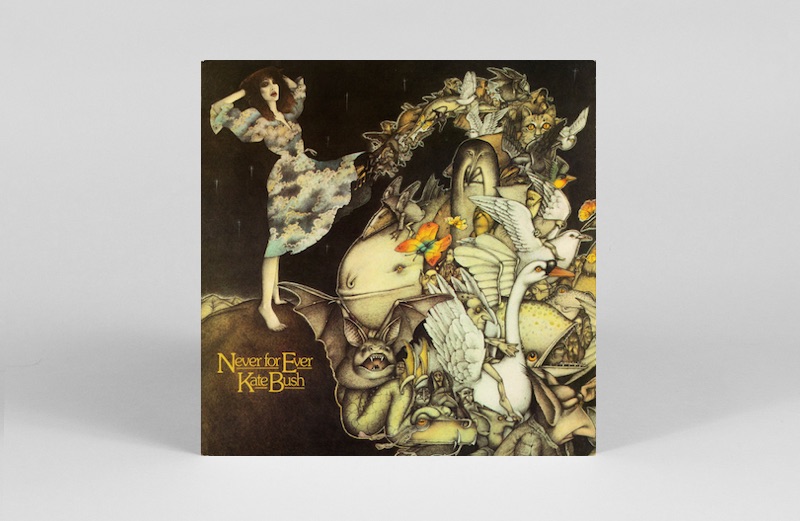

Kate Bush

Never For Ever

(CBS/Sony, 1980)

‘Babooshka’, the groundbreaking opener and longest charting single from Never For Ever, is often held up for its use of the Fairlight CMI: a sampler and audio workstation used to capture and manipulate the sound of smashing glass. However, there is also a superb CS-80 riff, which sits perfectly alongside fretless electric bass and an assortment of unusual textures. Bush uses the CS-80 once more on this, her first number one album – pairing it with a whistle-like Fairlight setting and acoustic piano, to create a rich and punchy introduction to album cut, ‘All We Ever Look For’. Following 10cc’s use of the CS-80 on album Bloody Tourists, this could be considered its second significant injection into the British pop sphere.

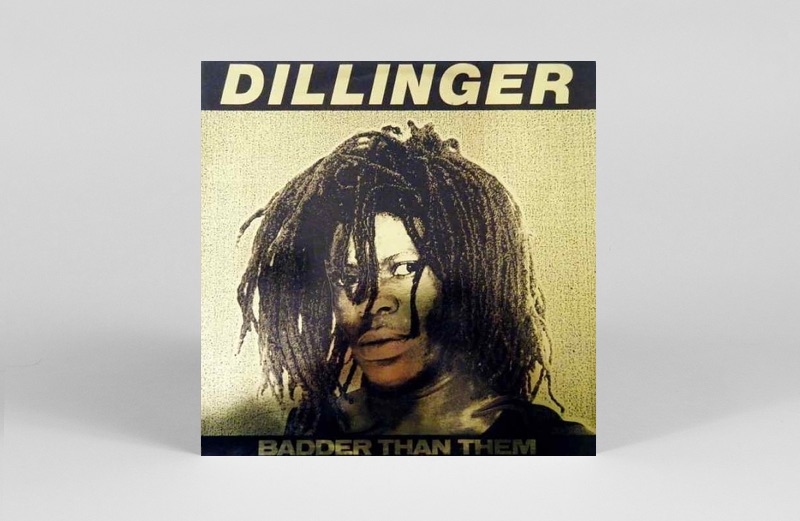

Dillinger

Badder Than Them

(A&M, 1981)

Ken Elliott, once of the psychedelic prog band Second Hand, was a key player in London’s reggae scene. During the early ’70s, he was involved in two groundbreaking sci-fi themed reggae albums, Star Trek by The Vulcans and Interstellar Reggae Drive. From that point on, Ken Boothe, Dillinger and Keith Hudson all called upon Elliott’s synth services. In 1980, Dillinger cut Badder Than Them at Strawberry Studios South, where 10cc had recorded Bloody Tourists two years earlier. Despite some tasty rhythm tracks, the album was another poor performer. ‘Tallowah’ has a busy arrangement, with two or three noteworthy synth components: an upfront, squelchy bass, panning pitch-bent high tones and a soft delayed sound resembling a steel pan – all within the sonic range of the CS-80. Its most notable use is on penultimate track ‘Remember’, which contains a patch seemingly identical in sound to one used on the next record in this list…

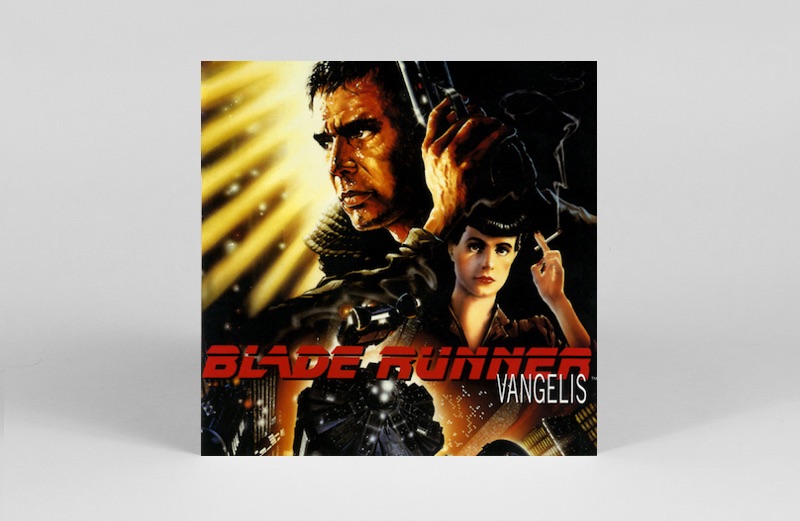

Vangelis

Blade Runner OST

(EMI/Atlantic, 1982)

This is the big one. The game changer. Vangelis’ epic score to Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner. From the delicate title theme to the dark outro, Vangelis demonstrates the synth’s versatility across the sonic spectrum: playing a graceful melody with a spine-tingling downward glissando on the ribbon controller during the opening theme, utilising the polyphonic aftertouch on ‘Blush Response’ and exploring its breathtaking high timbre on ‘Blade Runner Blues’. The notion of ‘retrofitting’ – adapting old systems with newer technology – is an idea that is integral to the architecture of Blade Runner and is cunningly mirrored in the score. Vangelis’ compositions have the same drama, delicacy, depth and darkness of the great ’30s and ’40s Hollywood scores, but where otherworldly textures take the place of traditional strings, brass, woodwind and percussion. It is a triumph of synthesised music that, ironically for Yamaha, would’ve been the best piece of marketing they could ever have hoped for…had it arrived five years earlier.

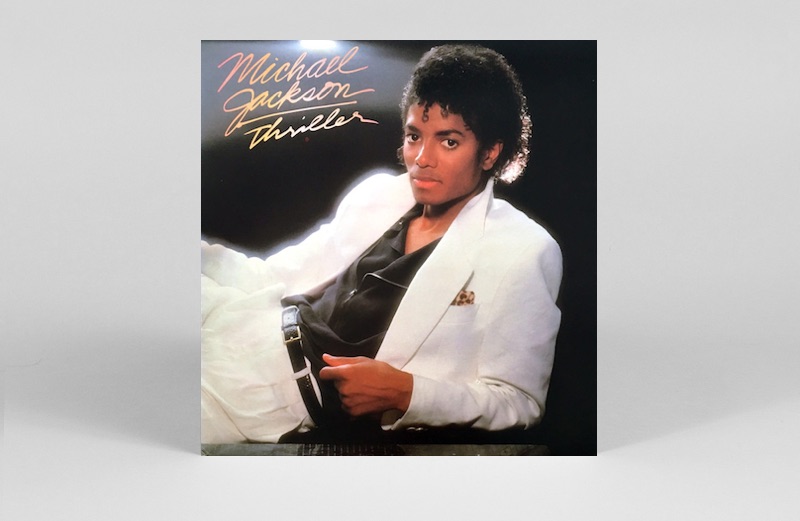

Michael Jackson

Thriller

(EMI/Atlantic, 1982)

Blade Runner was a challenging film, and although screenings were well attended, it wasn’t a box office smash or a huge award winner. By contrast, Michael Jackson’s Thriller had an instant impact. According to engineer Bruce Swedien, Quincy Jones and his team of supremely talented musicians wanted the album’s sonic values to “recharge the industry”. Sonically, it is indeed astonishing, thanks in part to a variety of synthesisers used, one of which was the CS-80. The four-chord vamp that introduces ‘Billie Jean’ is a multi-layered string synth part that included the CS-80. The synth strings on ‘Human Nature’ is a CS-80 with chromatic rather than portamento glide, played by Steve Porcaro of Toto, who had used the same synth to chart-busting effect on ‘Africa’ earlier that year. Both albums contributed to the significant impact the synthesiser made on the sound of popular music in 1982.

Michael Shrieve, Kevin Shrieve and Klaus Schulze

Transfer Station Blue

(Fortuna, 1984)

Having made his name as a percussionist with Santana, Michael Shrieve boldly turned his back on rock in the mid ’70s, in favour of the Berlin school. He met German musician and former member of Tangerine Dream Klaus Schulze while playing in Stomu Yamashta’s short-lived band GO, and it didn’t take long before they were recording together. The combination of natural acoustic percussion, pulsing synth leads and drifting pads, gives the music of Transfer Station Blue an almost Balearic character, finding a middle ground between dance music and ambient. The CS-80 shines through on second track ‘Nucleotide’, which begins with a beautiful synth passage, reflecting the unsettling character that the CS-80 offers. Schulze also uses one of the earliest wavetable synths on this record, showing how much development had taken place in the eight years since the CS-80 was launched.

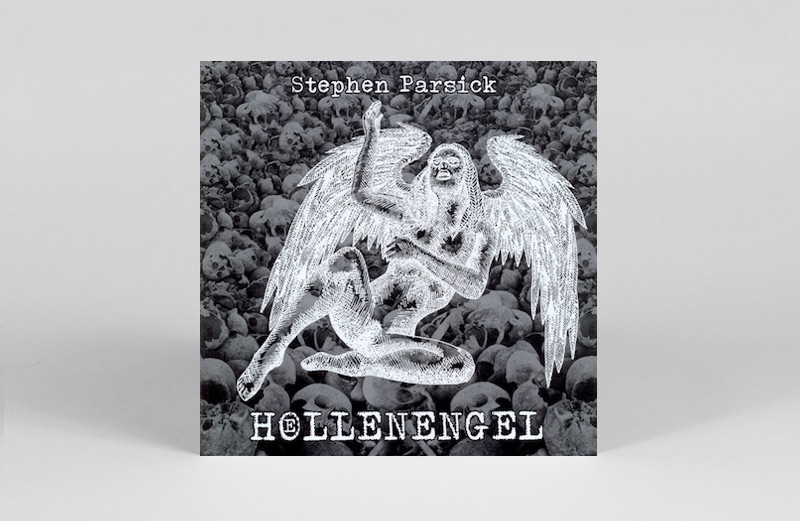

Stephen Parsick

Hoellenengel

(Doombient, 2005)

Although the artwork may suggest otherwise, synthesiser enthusiast Stephen Parsick’s magnum opus is neither a metal album nor an industrial record. This, as the label states, is dark, ambient electronic music. Recorded straight to DAT by Parsick himself, he avoided “computers, sequencers, MIDI interfaces or multitrack recorders,” in favour of pure CS-80 performances, captured with remarkably clarity alongside his Roland VP-330 vocoder, Minimoog and Fender Rhodes. By Parsick’s own admission, the setup is very similar to the one Vangelis used to create the Blade Runner soundtrack. As a result, Hoellenengel opens up a very similar sonic world. Given how much Parsick composes in the bass region of the instrument and how little he does to manipulate or interrupt the sound of the CS-80, you could argue that this album shows off the unbelievable power of the synth even more than Blade Runner.

Jesper Kyd

Borderlands: The Pre-Sequel – Claptastic Voyage OST

(Sumthing Else Music Works, 2014)

California-based video game composer Jesper Kyd is another devotee of Vangelis, whose use of the CS-80 for video game soundtracks stems back to his 2003 score for Freedom Fighters. Kyd calls it his “grand piano” and uses it extensively on this incredibly broad collection of music. Songs like ‘Lunar Surface’ contain both the high CS-80 shrieks and rising, imposing pads. Kyd believes that ’70s technology was about the quest to achieve the perfect sound, as opposed to today’s technology, which is more concerned with price and portability. He also demoes his CS-80 in the credits to the Bound to Sound documentary, showing off how he manipulates and processes the sounds as he works.