Published on

August 8, 2023

Category

Features

Faisal Hussain talks us through archiving 3000 records from Oriental Star Agencies.

Having your pick of 3000 records in a dusty backroom is a crate-digger’s dream, and it’s one that Faisal Hussain has lived. The Birmingham artist is the director of the True Form Projects vinyl archive–the largest South Asian vinyl collection in the UK. Rescued by Hussain from Muhammad Ayub’s Oriental Star Agencies– a Birmingham-based store that imported Indian and Pakistani music until its closure in 2017–the collection has spent the last three years being archived by Hussain and a team of volunteers.

Read more: A massive South Asian vinyl collection is set for exhibition in Manchester

Following the launch of the archive’s first exhibition at Manchester Museum this month, Kelly Doherty catches up with Hussain to find out more about the archive and how it came into his hands.

Faisal Hussain’s first introduction to Oriental Star Agencies stemmed from his early youth, “I used to go there with my dad occasionally, mostly for him to pick up tapes and later CDs”. Hussain recalls the double-pack cassette tapes his father would collect, but the shop was more his “dad and grandad’s joint” with him going infrequently.

After attending college and falling in love with music, Hussain’s interest in the store was piqued–culminating in his involving it in a project he was working on. “The project was called The History of Asian Youth Culture,” explains Hussain. “We were looking at culture in Birmingham and places of memory. The shop was one of the key places”. The project saw Hussain establish contact with Ayub for “photographing and collecting stuff”.

This initial encounter wasn’t the end of Ayub and Hussain’s relationship, however. In January 2017, Hussain received a call from the store owner saying Oriental Star Agencies had to close. After being offered the opportunity to pick out some items for his project, he went straight to the record store and witnessed chaotic scenes. “That process was mad. I had to use a freezer van to pick up what we could. We just put it in boxes. Initially, it was grab-and-go. There were other people, and it was a bit of a vulture-like scenario,” he laughs.

Whilst Oriental Star Agencies had largely made the move to CDs, as a vinyl collector, Hussain’s eyes were immediately drawn to a dusty section of records that were “not in the best state.” “It was a lucky coincidence that the vinyl was still there. Previously, it wasn’t the focal point of my work,” he says. “Then I realised we needed to be careful and stop the records from being used for a quick buck”.

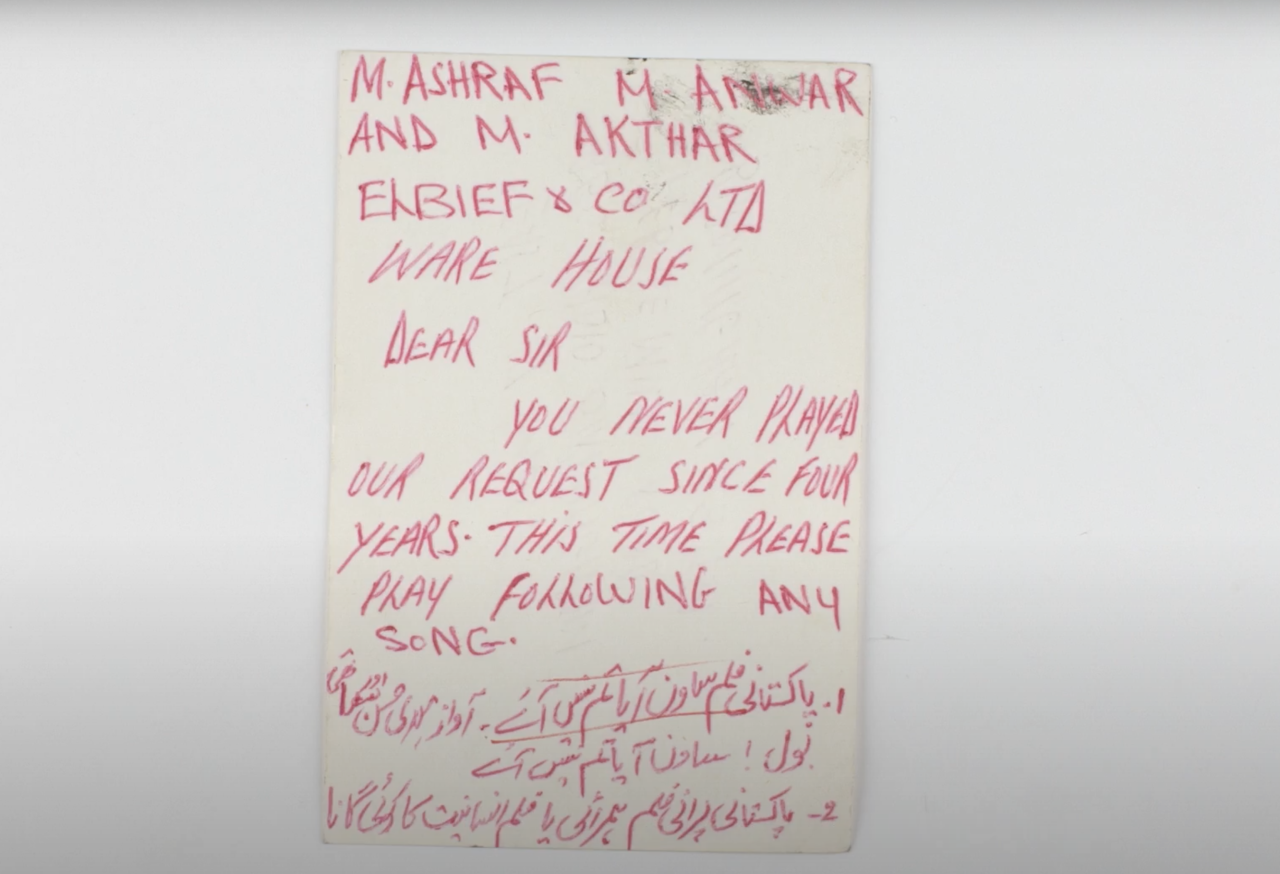

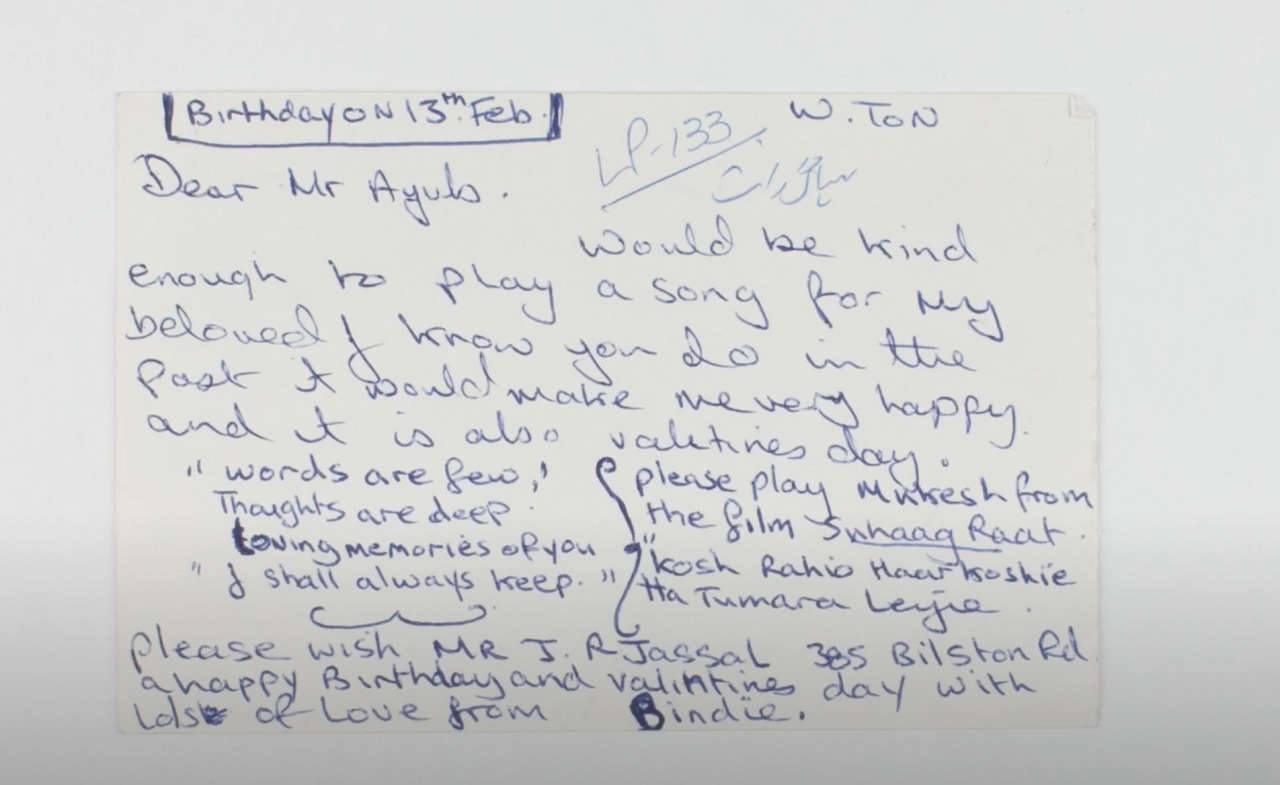

The collection itself was a treasure trove. Through “a couple of documents with the vinyl”, Hussain discovered it was largely two collections. “The first collection were records that Ayub played at the BBC Pebble Mill as part of one of his programmes,” he says. The programme, titled East in West, ran throughout the ‘80s on BBC Radio WM and had a segment where Ayub, alongside Anita Bhalla and Farah Durrani, played out songs from the collection whilst taking requests from its listeners. In many of these records, there are postcards or request cards from the radio show or personal notes left behind, a key reminder of the social context of this vinyl.

“It adds an alternative social history with how many people were asking for songs connected to their emotions,” Hussain describes. “There are people from the diaspora talking about weddings and wanting to celebrate like they would back home, but there are also unjust things–songs about losing love. We have two or three letters from prison and annoyed cards from people who’ve written in six or seven times and won’t write again until their record is played”.

According to Hussain, gems within the collection include spoken word records, music from Pakistan’s 1947 partition and a “one-off record about cricket supported by [Asian food company] East End Foods”. The second collection comprises 7”s–some Bollywood but mostly “rare records from Pakistan”.

Once the records were collected and safe in storage, the work began. Hussain made hard decisions about how to make the archive something for the community that was alive and could “last for hundreds of years”. With his own experience in museum archival work and the support of people like photographers David Rowan, Clare Hewitt and Vanley Burke and organisations including Art 360 and the Heritage Lottery Fund, Hussain decided upon how to document, photograph and collect the records.

“Archiving in this way was very much library-based,” Hussain explains. “We had to collect 10 to 12 bits of information per record for 3000 records. That’s all typed in by me and some volunteers and we’ve only got a fifth of them photographed so far. It’s a labour of love but we know, at the end of it, we’re going to have this reference point and prosperity ”.

Vinyl marketplace Discogs has proved a useful tool for the team, alongside a couple of sites dedicated to Bollywood and Lollywood, but research hasn’t been without its troubles. “A lot of these labels are defunct or one-hit wonders,” Hussain says. “The industry wasn’t as sophisticated back then–sometimes designers weren’t named or photographers weren’t attributed”.

Patterns in the information make the process easier with EMI and artists like Mohammed Rafi, Asha Bhosle, Lata Mangeshkar and RD Burman showing up frequently. “It’s a lot of detective work,” Hussain says.

Recently, the archive hosted its first event. Request Line saw the archive launch at the South Asia Gallery at Manchester Museum with an installation focused on sharing the records and requests from the East In West show, alongside a month-long residency of an exhibition. While the exhibition is still in its early days, Hussain has noticed a broad demographic of interest, from young DJs to older people who remember the music the first time around.

“With the burgeoning scene of younger people from South Asian backgrounds who don’t necessarily want to play South Asian music but wanted to reinvigorate and rebuild it, we’ve had a lot of support,” Hussain explains. He recalls that at the launch event, an older man took the mic and explained the background of a record before singing to the entire audience. “We’re finding that the older generation wants to explain the lyrics and songs, the younger generation wants to remix and make new stuff,” Hussain says.

Moving forward, Hussain and the team at True Form Projects have a wealth of directions they want to go with the archive. From plans to play records to older people with dementia to a photography exhibition and VR, this massive vinyl archive will be busy in the community, far away from dusty shelves.

Request Line runs at the Manchester Museum until August 17. Check out True Form Projects’ online archive here.