Published on

March 12, 2017

Category

Features

Its incomparable strangeness, beauty and bravery will stun any one of any age in any era. On its 50th anniversary, Martin Aston goes track-by-track to argue that The Velvet Underground & Nico is the most influential rock album of all time.

As a result of believing in everything that David Bowie talked about and stood for, and his covers of Velvet Underground songs ‘I’m Waiting For The Man’ and ‘White Light White Heat’, I’d bought The Velvet Underground & Nico in late 1972 without hearing a note. I was rewarded by my malleable 14-year old mind being blown as much as by the sight of Bowie’s cat-suited alien rocker with sticky-out red hair.

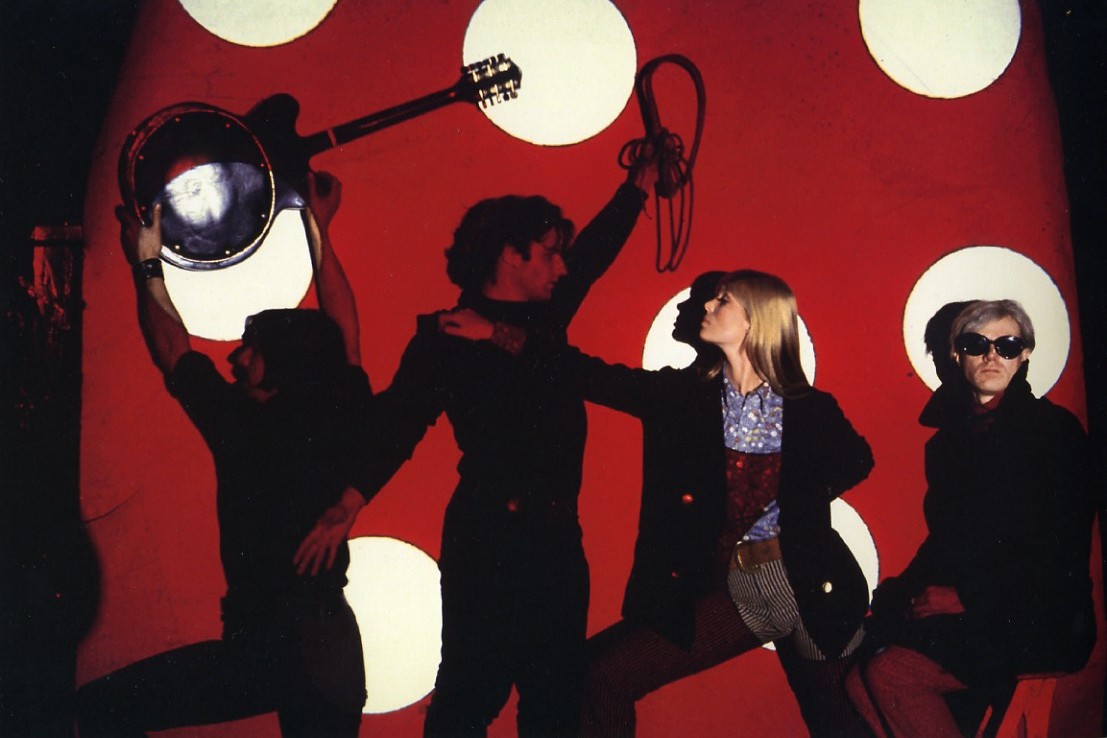

Let’s start with the art: a bunch of surly faces, several wearing sunglasses, or blank stares, the antithesis of whatever ‘pop’ presentation I’d imbibed through Top Of The Pops, and blurry live shots with giant backdrops of vacant eyes, alongside excerpts of reviews that were often critical (I was to later learn that the only positive comments were inserted by the record label, Verve, to stem the tide of negativity). Punk rock!

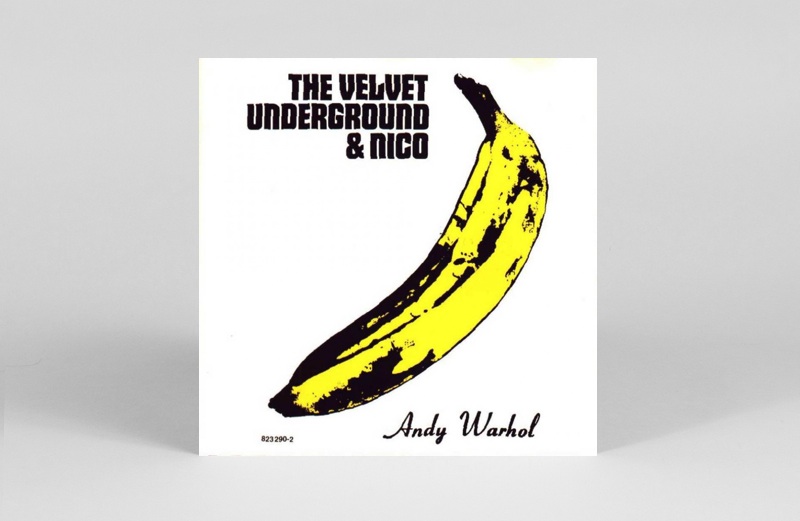

And the cover: a giant yellow banana (sadly, mine didn’t peel, to reveal a pink version underneath, as the 1967 original had), above the words ‘Andy Warhol’ (the artist, the designer of the artwork, and also listed as the album’s producer), and no mention of the New York band who’d made the record. And the music! A more assaultive record, given the context of the era, has yet to be made. Dreamy weirdness crossed with dirty noise, slow and fast, as much driven by a droning viola as needling guitar, and all laced with all manner of taboo topics: drugs, sadomasochism, more drugs, and random scattershots of strange behaviour that I had no means of understanding.

This was, in the main, the way The Velvet Underground infiltrated Britain. When the album had been released, it won only a very occasional (and often dismissive) review, and over the course of their four studio albums (let’s not count 1973 impostor Squeeze), they never played here. It was only after principal singer-songwriter-guitarist Lou Reed had left, and latter day guitarist Doug Yule moved to the front, did an unscrupulous manager ship a Velvet Underground over, staffed by session musicians.

Ironically, there is a similarity to the presentation for The Velvet Underground & Nico’s 50th birthday celebrations, in Liverpool on May 26th, to be staged by John Cale, the band’s original violist, pianist and occasional singer, as Lou Reed and guitarist Sterling Morrison are no longer alive – likewise their singing German associate Nico – while drummer Mo Tucker is seemingly retired. Cale will be calling on various instrumental and vocal guests, as he did in Paris in April 2016 (in the 50th year since the album was recorded), including Mark Lanegan, Animal Collective and The Libertines’ Peter Doherty and Carl Barât.

If Cale’s avant-garde sensibility doesn’t allow for nostalgic recreations of the past, and his Paris 2016 versions showed his current interest in hip hop and electronica (most ‘sacrilegious’ on a digitised ‘There She Goes Again’), traditionalists would have appreciated a suitably languid ‘Femme Fatale’ (sung by smoky-toned Frenchwoman Lou Doillon), a rambunctious ‘Run Run Run’ and the alternative prowling nocturne of ‘Waiting For The Man’. But wherever Cale will go with the birthday party, it will be rapturously welcomed; contrast with 1967, when it charted at 171 in the US, and sold reputedly 30,000 copies in its first five years.

If The Beatles’ early albums influenced a greater volume of bands at the time, The Velvet Underground & Nico has had a more prolonged and widespread effect, and was far more iconoclastic in its uniqueness, reach and range. As writer Simmy Richman put it, “On that first album alone, the Velvets invented – or at the very least inspired – art rock, punk, garage, grunge, shoegaze, goth, indie and any other alternative music you care to mention.”

‘Sunday Morning’

Written to order as a single after the record’s true producer Tom Wilson (as well as being the band’s de facto manager and benefactor Andy Warhol was on the record as a marketing device) couldn’t hear one, plus he wanted more material for model and ‘chanteuse’ (as she’s credited on the album) Nico, who he – alongside Warhol’s contingent – considered a more suitable front for the band. Lou Reed loved a songwriting challenge, and with Warhol suggesting the theme of paranoia, ‘Sunday Morning’ was written after a night of amphetamine, Sunday morning coming down. Reed got his revenge on Wilson and Warhol by insisting he sing the song himself once it was recorded, in a dreamy Nico style. It’s the album’s lushest track, with Cale’s celeste producing glockenspiel-like softness to add a cushioning layer of gauze, as superficially innocent as a slice of teen pop. However, with Verve lacking confidence in their maverick signing, the song – as the VU’s second single – was barely even pressed, let alone promoted.

‘I’m Waiting for the Man’

The deceptive allure of ‘Sunday Morning’ was the sheep’s clothing for ‘I’m Waiting For The Man’, a primitive rocker that shows the Velvets’ original (i.e. before Nico arrived) intent, as a surly avant-garage band mixing Reed’s love of R&B and pop with Cale’s experimental classicism. The two tracks were instant proof of the Velvets’ pioneering light/dark contrast – melody and atonality, music designed to seduce and disturb.

Cale’s pounding piano, smacked with his fists, is the main driver behind Reed’s shocking – for the time – matter-of-fact first-person narrative of purchasing a $26 bag of heroin (equivalent to around $200 today) in a Harlem brownstone, the first evidence of his vision of rock’n’roll, to match the literary scope of writers such as Hubert Selby and John Rechy, who peppered their hard-boiled novels with drugs, violence and sexual liberation. ‘I’m Waiting for the Man’ is also notable for being the sole Velvets song that Reed, Cale, Tucker and Nico all tackled solo.

‘Femme Fatale’

Whoever sequenced The Velvet Underground & Nico felt it needed front-loading with ballads, which accounts for the placement of ‘Femme Fatale’, also suggested by Warhol, to give Nico more songs to sing. She gave it her best velvet croon, in the days before heroin harshed her dreamy nonchalance, though one wonders if she recognised the song could have been about herself, as one of the gorgeous, aspiring and damaged women circling Warhol’s flame at his art/business headquarters The Factory. Like ‘Sunday Morning’, ‘Femme Fatale’ showed Reed’s disciplined songwriting nous, his natural talent sharpened by gun-for-hire work at Pickwick Records before he formed the Velvets, where he mastered a succession of genres; though this ballad is not doo-wop, the foreground/background vocals show an awareness of the genre. 37 cover versions (according to Wikipedia) attest to the song’s timeless spell.

‘Venus in Furs’

No Pickwick exercise would have prepared Reed for ‘Venus In Furs’, an ode to sado-masochism (Taste the whip / in shiny, shiny leather) named after the book by Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, which Cale dominated by way of his uncanny viola drones and scrapes (approximating a ‘whip’ motif) at the spearhead of an uncanny arrangement, like a slow funereal march in medieval times – altogether a first for popular music. Tucker’s drums were a couple of bass thuds and a tambourine, like a classic Phil Spector backbeat arrangement bled dry of reverb. Cale’s sound was learnt from working with La Monte Young and Tony Conrad in the avant-garde Theatre of Eternal Music troupe (also known as The Dream Syndicate), while Reed had an experimental side, namely his ‘ostrich’ guitar, where every string was tuned to the same note. Or as Cale put it, “I wanted to push the envelope and fuck the songs up.”

‘Run Run Run’

The album’s sequencing is spot on; after the slow, suspenseful agony of ‘Venus In Furs’, ‘Run Run Run’ was a rumble in the urban jungle (“You felt as if you were on the New York streets, living the song out,” Cale reckoned), or a runaway train of a song, riding the rails of 1950s hoodlum rock’n’roll and rhythm guitars straight out of Bo Diddley and Chuck Berry – “a chukka-chukka bluesy groove,” Cale added – while Reed and Morrison uncoiled serpentine guitars.

Lyrically, Reed was back on a drug run, but describing this time a cast of characters searching for a heroin fix; but what do we make of Teenage Mary, Margarita Passion, Seasick Sarah and Beardless Harry (a precursor of his verse-by-verse cast habits on ‘Walk On The Wild Side’)? They sound like a wayward bunch of drag queens to me, or a cast street hustlers: or just a bunch of junkies: as Reed’s chorus repeats, Gypsy Death and you… All this in the so-called summer of love – the Velvets presented another, more chilling reality.

‘All Tomorrow’s Parties’

An edited version – half as long, at three minutes – was released as the Velvets’ first single, since it was sung by Nico, likewise the B-side, ‘I’ll be Your Mirror’. Just what would radio programmers have made of its undulating, shuffling spell, and Nico’s vocal – “her big Germanic Marlene Dietrich way” recalled Cale – which perfectly fit the lyric’s ever-so-bored mindset, even if the song wasn’t written with her voice in mind. Moe Tucker’s drums again cast a Spector-ish pall over proceedings, but this time, the band created a Spector-ish wall of sound to go with it, dominated by Cale’s minimalist mantra piano and Reed’s ‘ostrich’ tuning.

It was Warhol’s favourite Velvet Underground song, possibly because it was the song most inspired by his Factory crowd– the personalities, the drugs, the jaded smiles, the need for another high. Hidden inside, ‘All Tomorrow’s Parties’ is actually a great pop song, almost sing-song and upbeat – but being the Velvets, it sounds diseased and forsaken.

‘Heroin’

Reed wrote ‘Heroin’ while working at Pickwick, between writing “ten surfing songs,” he recalled. “I said, ‘Hey, I got something for ya.’ They said, ‘Never gonna happen, never gonna happen’.” Even in acoustic demo form, you can hear why – the slow, ominous mood, the lyric that vouches for heroin’s insulating charms, without passion, condemnation or disgust (did electro-shock therapy, supposedly for Reed’s teenage anxiety and misanthropy, but also possibly his emerging homosexuality, remove a layer of expression/empathy?) – another matter-of-fact missive in an era where other songwriters were tangling themselves up in metaphors.

But once on record, ‘Heroin’ scaled a new high. At the risk of repeating myself, ‘Heroin’ still doesn’t sound like anything in rock’n’roll, despite all the Velvets impersonators and acolytes. The giddy tempo shifts have been copied, but not this hallucinatory combination of shrieking crescendos and sudden lulls, mirroring the rush and settling effect of another insulating fix, via a see-sawing viola and thumping mallets.

‘There She Goes Again’

Next to the album’s most disturbing chapter is its poppiest, the one song on the album that you can dance to. Reed wrote ‘There She Goes Again’ during his Pickwick era, and it’s the closest song to the genre-specific singles (released under band names such as The Roughnecks and The Primitives) that Reed wrote and recorded. In this case, the guitar intro to Marvin Gaye’s ‘Hitch Hike’, “with a nod to The Impressions,” Cale added, is re-appropriated for a gritty upbeat rocker with a breezy vocal melody and catchy lyric, another Reed’s putdown, but one couched in phrases in line with pop’s teen melodramas. – why this song was passed over as a Velvets single is mystifying, except that it’s Reed singing, not blonde beauty Nico – the real reason Verve signed the band to begin with.

‘I’ll Be Your Mirror’

Nico’s favourite Velvets song, “of infinite desire, strangely tender for us,” said Cale, which she unwittingly inspired after she approached Reed after a show, saying, ‘Oh Lou, I’ll be your mirror.” Responding to this Germanic ‘ice maiden’, Reed found a level of emotional complexity that rivalled Nico’s own conflicted upbringing (growing up under Nazi rule, she experienced the breakdown of her soldier father, and then rape by an American GI), while falling for her romantically (as did Cale). Though Reed resented the attention Nico got, and pushed her out of the limelight as soon as he could, without these ballads that he was asked to write for her, the Velvet Underground’s debut would have been much more slanted toward the dark side, and so would have been less of the multi-dimensional and broadly influential marvel that it is.

‘The Black Angel’s Death Song’

After the album’s sweetest spot, its most dissonant. The song that got the Velvets banned from their New York residency at Greenwich Village’s Café Bizarre, ‘The Black Angel’s Death Song’ sprang from Reed’s lyrics, an onomatopoeic exercise – while studying English at Syracuse – in free expression (Cut mouth bleeding razors / Forgetting the pain / Antiseptic remains cool goodbye / So you fly) that is the closest Reed got to Dylan’s surreal metaphors – the reed’s slurring vocal style compounds the comparison. But Cale’s arrangement doesn’t recall a single Dylan setting, with a melody resembling a sea shanty, but giddy and seasick given by Cale’s see-saw viola and his periodic vocal hisses into the microphone, like gas escaping from under the floorboards. Here’s one song that very few people have tried to cover.

‘European Son’

The album finale also doesn’t invite covers. When I bought the album, I thought the finale was called ‘European Son To Delmore Schwartz’, as the songwriting credits put it, which always fascinated me – a journey from where to where? And what sort of destination was Delmore Schwartz? I subsequently discovered he was Reed’s poetry professor, and that Reed had dedicated the track – the album’s longest, at nearly eight minutes – to Schwartz because it had the fewest words (Schwartz detested lyrics, calling them “disgusting” and “awful”. It’s doubtful he ever got to hear ‘European Son’ as he died (from alcoholic poisoning) three months after it was recorded, and he might have thought the music “disgusting” and “awful” too.

“A big rave noise, fantastic for ending a show with,” Cale claimed, was born out of an early VU jam ‘Miss Joanie Lee’, and further improvised in the studio, including a chair dragged over aluminium studio plates, a sound that Cale likened to “a plate glass window being smashed” that signalled the all-out rumble, distortion and feedback that lasted a full six minutes, before finally slowing down and stopping in a haze of electrical hum, as if the amplifiers were finally depleted. A fitting end to a record that, 50 years on, still sounds remarkably fresh and new, and capable of surprise and shock.