Published on

October 15, 2014

Category

Features

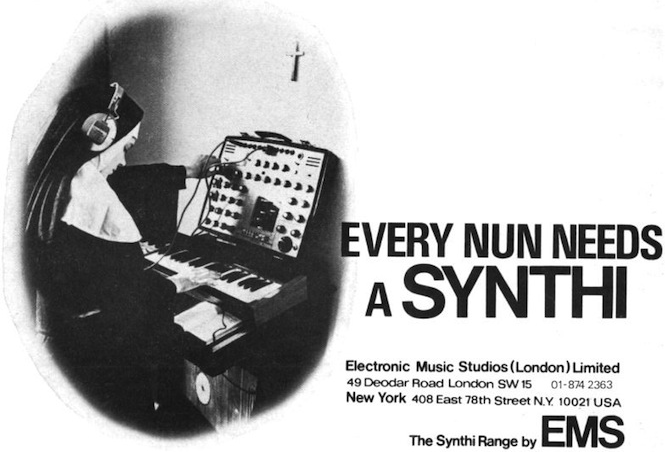

The VCS3 takes up a special place in the history of synthesizers – educational tool come avant-garde studio in a box, highly idiosyncratic and melodically unstable, a melding of technological ingenuity with cost-effective army surplus electronics – it was never designed for conventional music yet its application and legacy have endured.

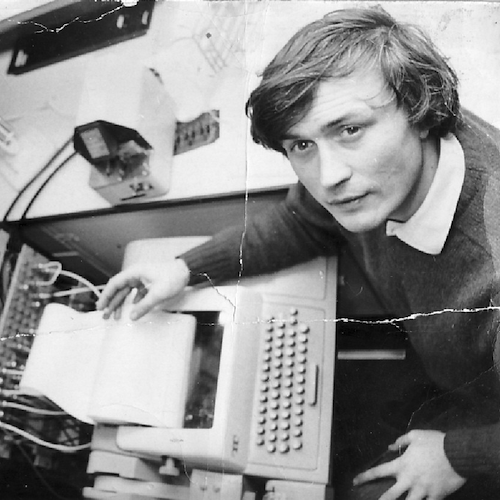

The product of a revolutionary group of thinkers in sound, electronics and computation who came together under the banner of Peter Zinovieff’s Electronic Music Studios (EMS), the VCS3 was the answer to the financial upkeep of Zinovieff’s one-of-a-kind Putney based music studio which housed one of the first privately owned computers in the world. In comparison to the other systems on offer in 1969 the VCS3 was to be an affordable and portable box-of-tricks, a child of the EMS studio-proper, which would provide financial fuel to Zinovieff’s constantly expanding ideas on refining the relationship between sound and electricity.

It’s Zinovieff’s electronic score that still adorns the Cybernetic Serendipity Music LP and his PDP8 computer that formed a key part of the ICA exhibition – with its ability to sample and respond to whistled input – but it’s the VCS3 which Zinovieff and EMS are most commonly associated with. Given the work and ambitions hatched at EMS and the Putney studio, this is understandably somewhat to Zinovieff’s chagrin, and it seems part in vitriol but more largely in sincerity at the end of ‘What The Future Sounded Like’ that he describes the studios legacy as having amounted to some “pathetic little synthesizers”.

The relative harshness of its creators (Zinovieff, David Cockerell and Tristram Cary forming the all important creative trio) can be in relation to their technological aims and indeed later advances, but this label is not the VCS3’s legacy in recorded and particularly experimental music. This chaos-theory in a box expanded notions of musical possibility largely through it’s irregularities, and had many prominent exponents, finding its way onto a number of key recordings, which is where this list picks up from.

For those who’d like to get a perspective on its sounds and foibles without diving head-first into retro-fetishism and visiting a bank manager to play the real thing, Jonny Trunk of Trunk Records has provided us with a delightful VCS3 app which can be found here. An app far more powerful than Zinovieff’s £4000 computer (circa 1965) that ultimately gave birth to it all.

Need more synth? Click here for an in-depth look at 13 more synthesizers that have shaped modern music.

See more from Machine Music Week:

Watch our short film on the first ever computer music compilation Cybernetic Serendipity Music

It’s a woman’s world: Ada’s top 10 techno records

The pioneering women of electronic music – An interactive timeline

Listen to the sound of the internet

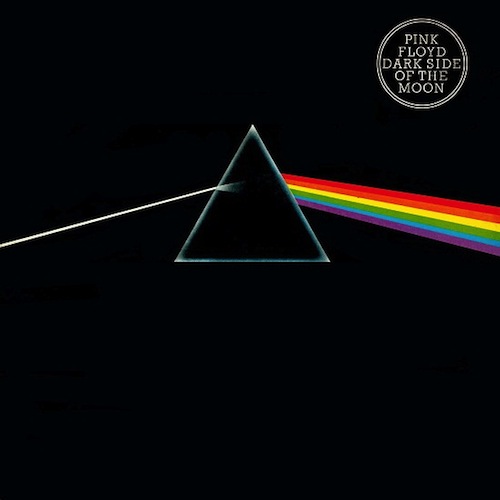

Pink Floyd

It was Delia Derbyshire who taxied Pink Floyd over to the Putney studios to meet Zinovieff and partake of the EMS world, and it marked the start of a relationship that would see the VCS3 and it’s Synthi upgrades become key elements of the Pink Floyd sound. Indeed whilst the traditional instruments always took the forefront, a listen to Dark Side of the Moon and a look at it’s back cover where all but Nick Mason are listed as performing on the VCS3 make its embracement clear. ‘On The Run’ is the VCS3 at it’s most musical, with the add-on sequencer and keyboard accelerating the pulse into a classic of machine-age, technology out of control paranoia.

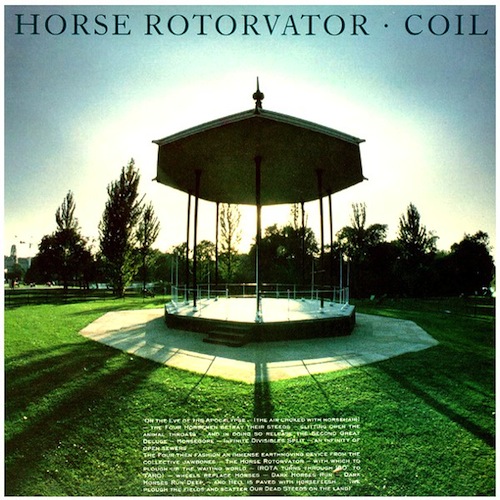

Coil

Coil were masters of atmospherics and channeling electronics into potent song forms that sought the beyond. Using an array of synths throughout their discography, they’re a prime example of the affect an “unstable” synth like the VCS3 can have on a listener when used in the right way, and make no mistake a listen to either volume of Musick to Play in The Dark in the prescribed manner will most certainly affect you. Distortion effects on Horse Rotorvator and guitar filtering effects on Love’s Secret Domain are particular examples of the VCS3’s use and a rare interview for the Culture Show (along with it’s semi-mocking commentary) starts with them ‘wrecking a nice beach’ with the tool of choice.

Klaus Schulze

The VCS3 often excelled with musicians who sought to forge new frontiers for electronic music, and with Klaus Schulze’s strain of kosmiche, it certainly found a home. His works in the 70s were steeped in science fiction and from Cyborg onwards the VCS3 – itself looking like the archetypal space ship control panel – provided texture and ambience to his visions. Take a listen to its combinations with the ARP 2600 on ‘Totem’ to see if the combination of two of the most desirable synths of that and indeed present time justifies the means. With the VCS3 still a part of his live set-up Schulze is the type of musician who after nearly 40 years of experience with the VCS3 still embraces it’s spontaneous quality and inability to create exactly the same sound twice.

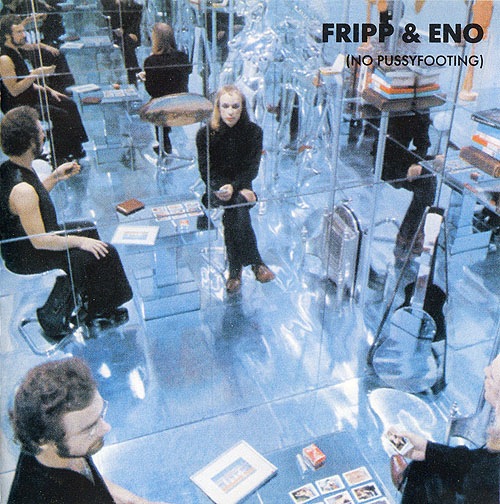

Brian Eno

This being his first synth – an instrument his name is irretrievably bound to – Eno has always been happy to expound on the VCS3’s virtues, and it’s been a recurring feature of his multi-faceted career. The non-musician with a head full of ideas, this was his instrument of choice for filtering and warping Roxy Music’s early sound, with later notable appliance to Robert Fripp’s guitar on the sublime ‘No Pussyfooting’ and atmospheric flourishes on David Bowie’s ‘Heroes’. His definition of ambience and ability to see new possibilities for electronic music had roots in the virtues and failings of the VCS3.

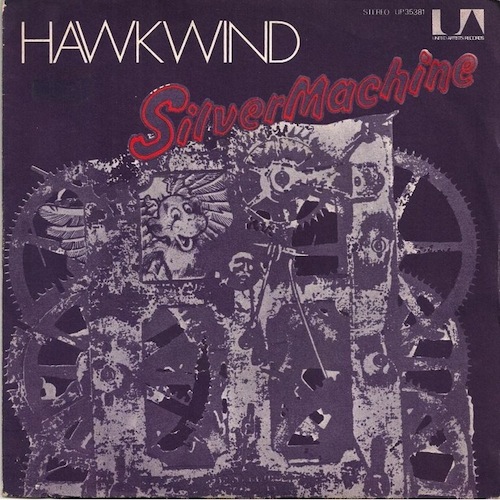

Hawkwind

For Hawkwind the VCS3 was a portable box of psychedelic sound that provided the “space” in their space rock. Looks and sound wise it fitted the sci-fi leanings of the band, and price wise it was the only affordable synth on the market at the time (£350). Dim Mak and Del Dettmar. were the men behind the controls of the electronic trip and that swirling vortex of sound that surrounds ‘Silver Machine’ is all VCS3.

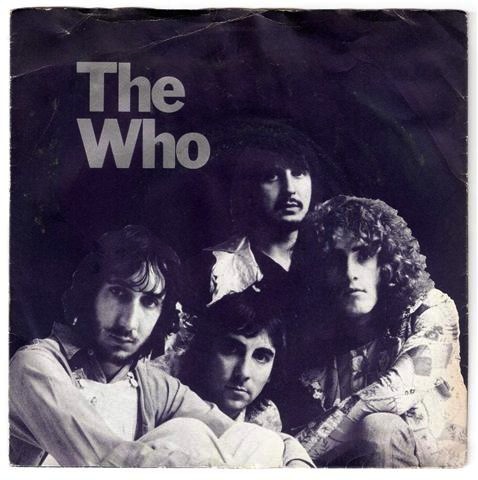

Pete Townshend

Outside of his guitar antics Pete Townshend is known for taking an early interest in synthesizers and the work of the Radiophonic Orchestra and Karlheinz Stockhausen. Amassing some state of the art machines in the form of the American made ARPs along with the VCS3 he sought to inject something of their nature into The Who’s sound. ‘Won’t Get Fooled Again’ is the most prominent example, as it used the VCS3’s audio-in function to filter and sample Townshend’s Lowrey organ, thus achieving the signature sound and the basis of a huge hit for the group.

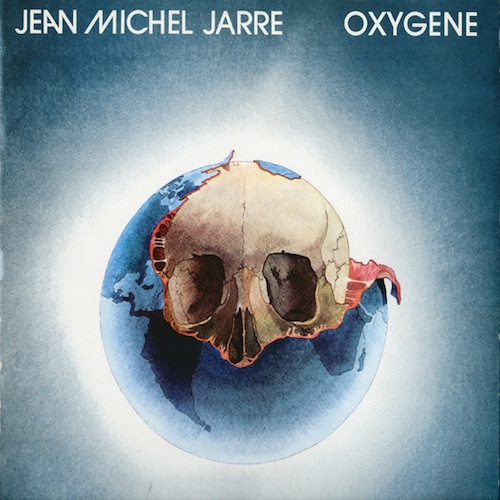

Jean Michelle Jarre

The sounds of the VCS3 were disseminated across different forms of music in a way its creators never envisioned (schools rather than musicians being the initial focus), and as the most prominent instrument on Jean Michelle Jarre’s Oxygene it was taken to the ears of another 12 million listeners. Never one to do things in a low key manner Jarre bought 6 VCS3s for his studio and live set-up, and the 30th anniversary re-recording still used his veritable host of analog electronics in homage to the pioneers who created them.

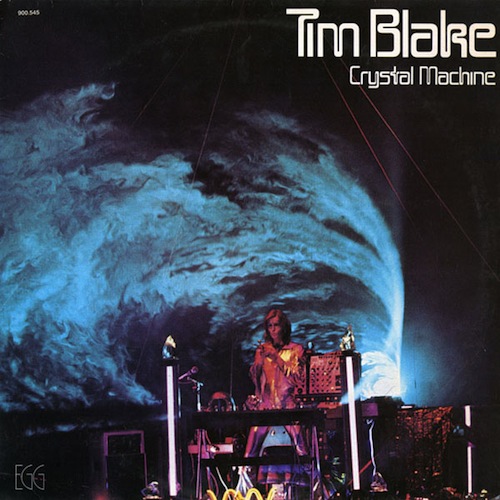

Tim Blake

A renowned synth player for his work with Gong and Hawkwind, Tim Blake’s 1977 solo opus Crystal Machine was in many ways a homage to the sound of the VCS3. Blake had created his ‘Crystal Machine’ by merging and customizing 2 VCS3s (the portable Synthi A versions) in a blue Perspex casing, opening up a range of new possibilities for the synths. It’s heard in full effect on ‘Last Ride of the Boogie Child’. A footnote here being that Tim was at one stage on the EMS sales team.

Peter Zinovieff

Zinovieff’s 60s and 70s works didn’t use the VCS3, it being a far less sophisticated version of his master studio, and pieces such as Chronometer or the recordings on the Cybernetic Serendipity Music LP are centred on the possibilities his computers provided – the VCS3 was always a means to an end for him. With the decline of EMS, David Cockerell moved onto other matters (Electro Harmonix, Boulez, and Akai all benefiting from his inventions) and with the loss of his studio Zinovieff turned away from music for 35 years until Russell Haswell encouraged him to get involved again. His current work with violinist Aisha Orazbayeva shows he hasn’t lost his touch, but now his behemoth PDP8s are gone with Max/MSP and Adobe Live software – creations that have origins in his pioneering work – being the tools of choice.

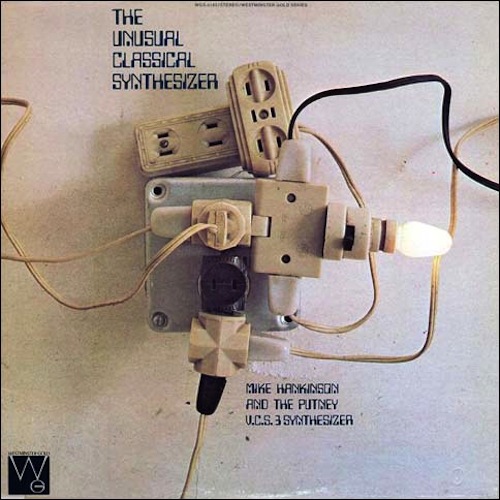

Wendy Carlos

The final entry in this list is of an artist whose sound was defined in opposition to, rather than in unison with, the VCS3. Wendy Carlos’ gifts to music and technology are well known- from her close relationship in developing Bob Moog’s synths to her pioneering Switched-On Bach – and her relationship with the VCS3 is somewhat different to the rest of this list as she stands out as one of its main critics. Citing it as “gimmick oriented” and “another great concept worked out in ignorance” it points to the important fact, that it wasn’t to everyone’s tastes and the Moogs which EMS eventually struggled to compete against were more conventionally musical and stable in holding a pitch. A master of the tape splicing musique concrete techniques that Zinovieff and EMS sought to do away with, Switched-On Bach was the product of Carlos’ ingenuity as much at it was the synth, and the recording was created in the tape splicing manner from individual synth tones. A 1972 LP by Mike Hankinson gave us Bach, Mozart and Beethoven on the VCS3 but it’s best to stick with Wendy on this one.