Published on

February 14, 2019

Category

Features

UK producer Inland’s An Invitation To Disappear score for Julian Charrière’s provocative film explores climate change, catastrophe and redemption on the dance floor – from an Indonesian volcano to the walls of Berghain.

Created as a response to the 200th anniversary of the Tambora volcano eruption, which plunged the world into darkness and caused a series of extreme weather conditions, An Invitation To Disappear first took shape as Inland’s soundtrack to Julian Charrière’s film set in an Indonesian palm plantation.

For his debut LP, and first release on Ostgut Ton sub-label A-TON, Inland, aka British producer Ed Davenport, reworked these soundscapes and field recordings into 8 tracks – spanning from stripped-back, industrial realms of techno to more ambient, lush tropical shades.

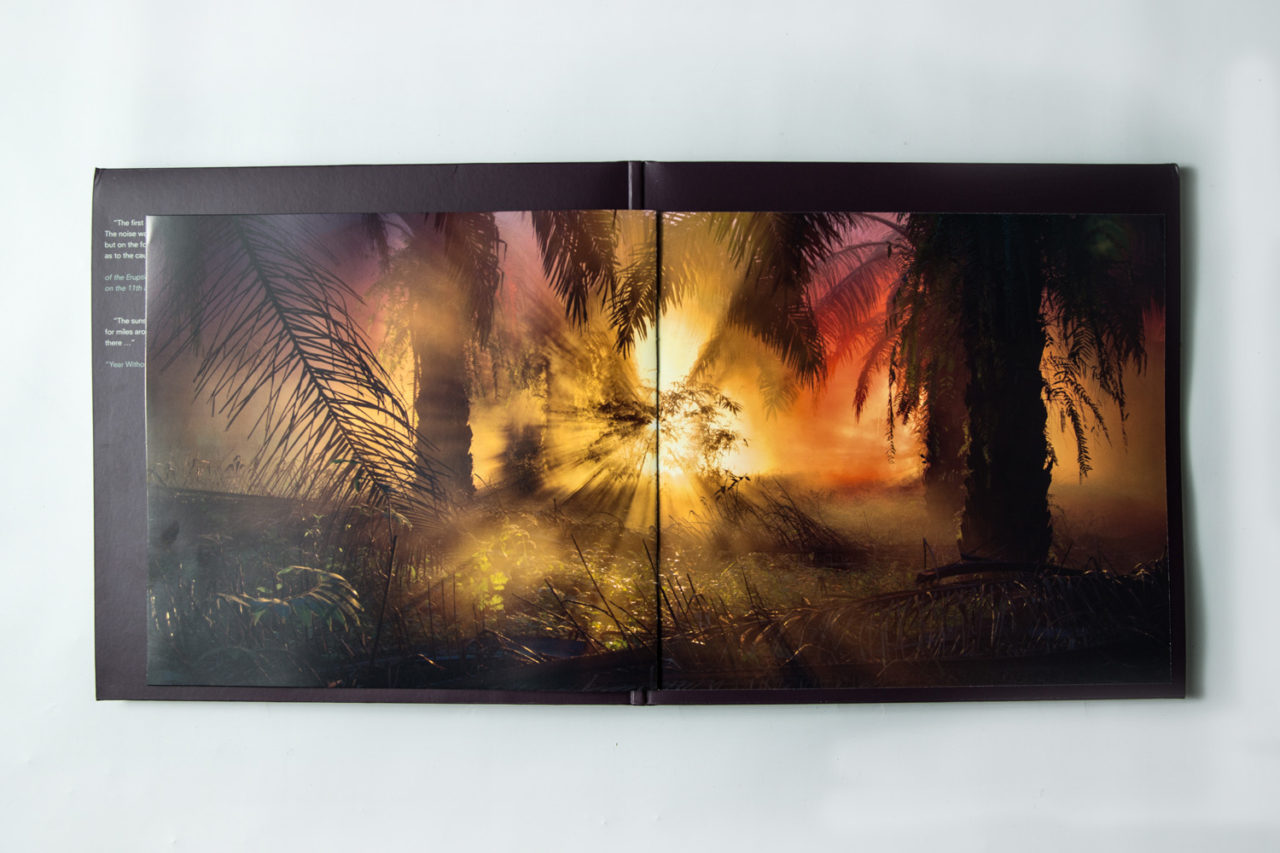

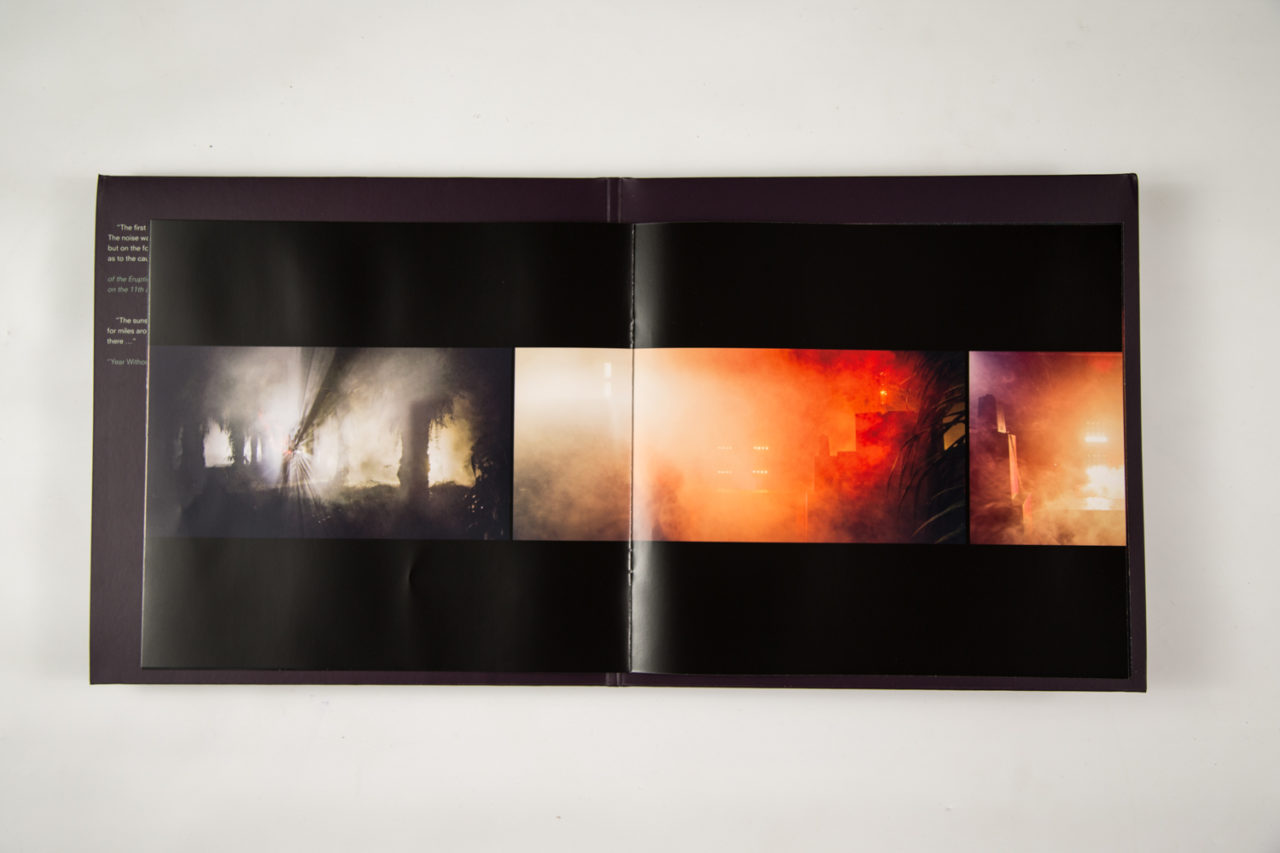

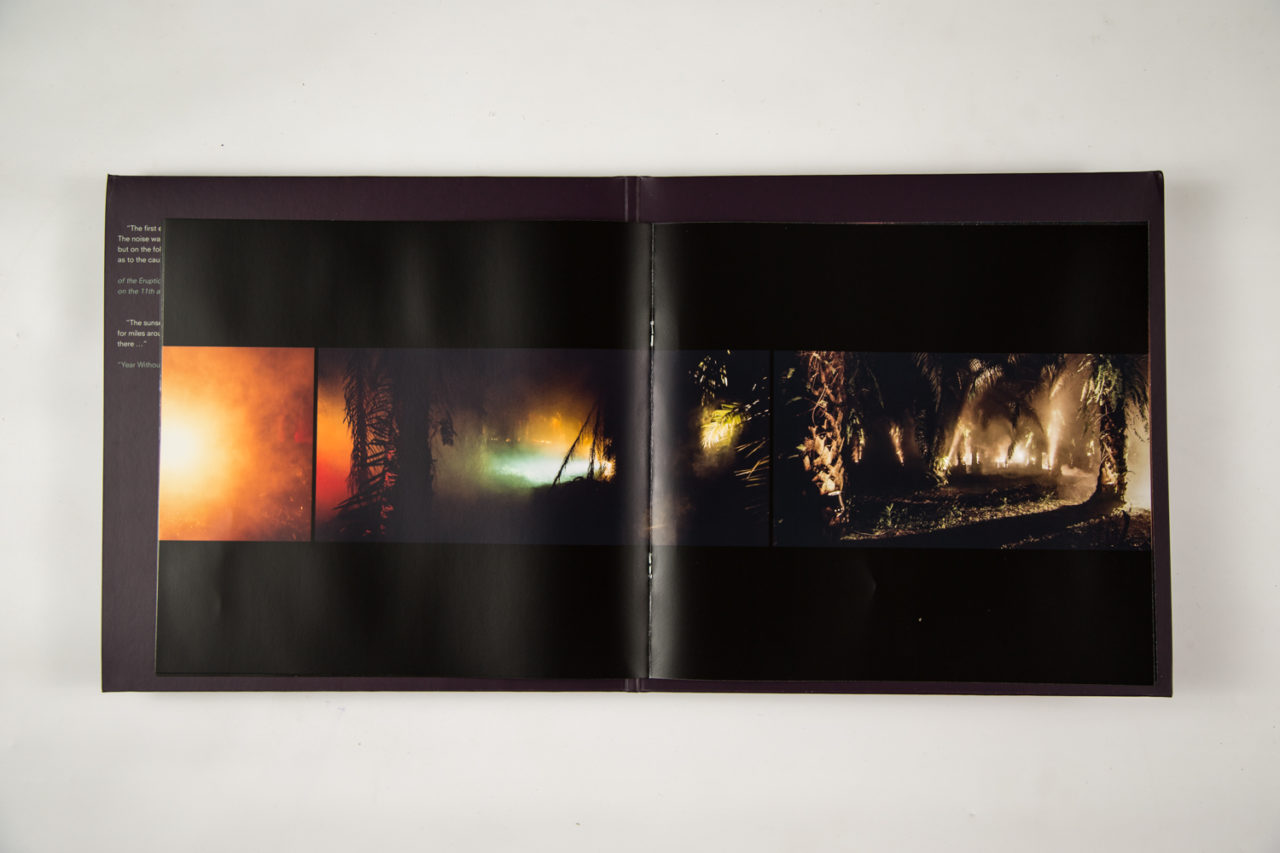

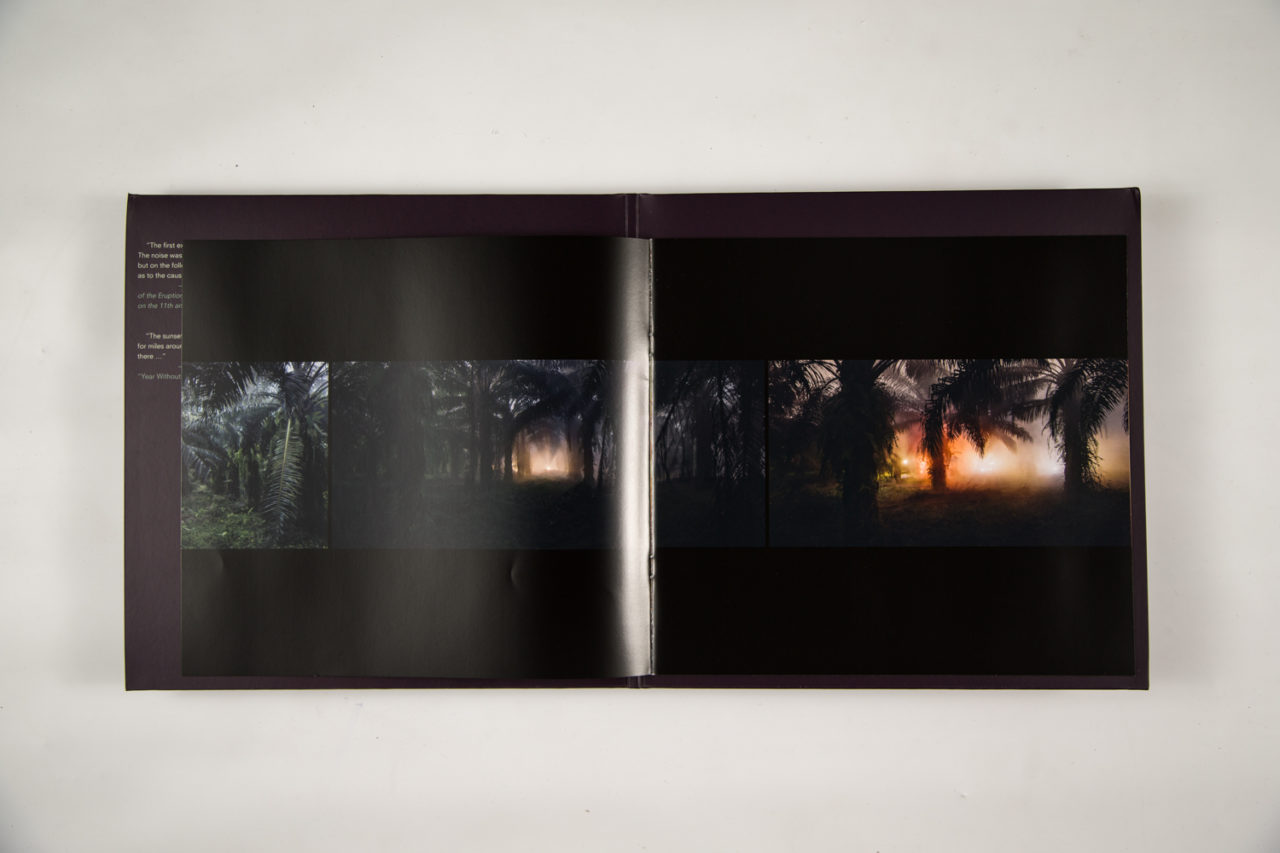

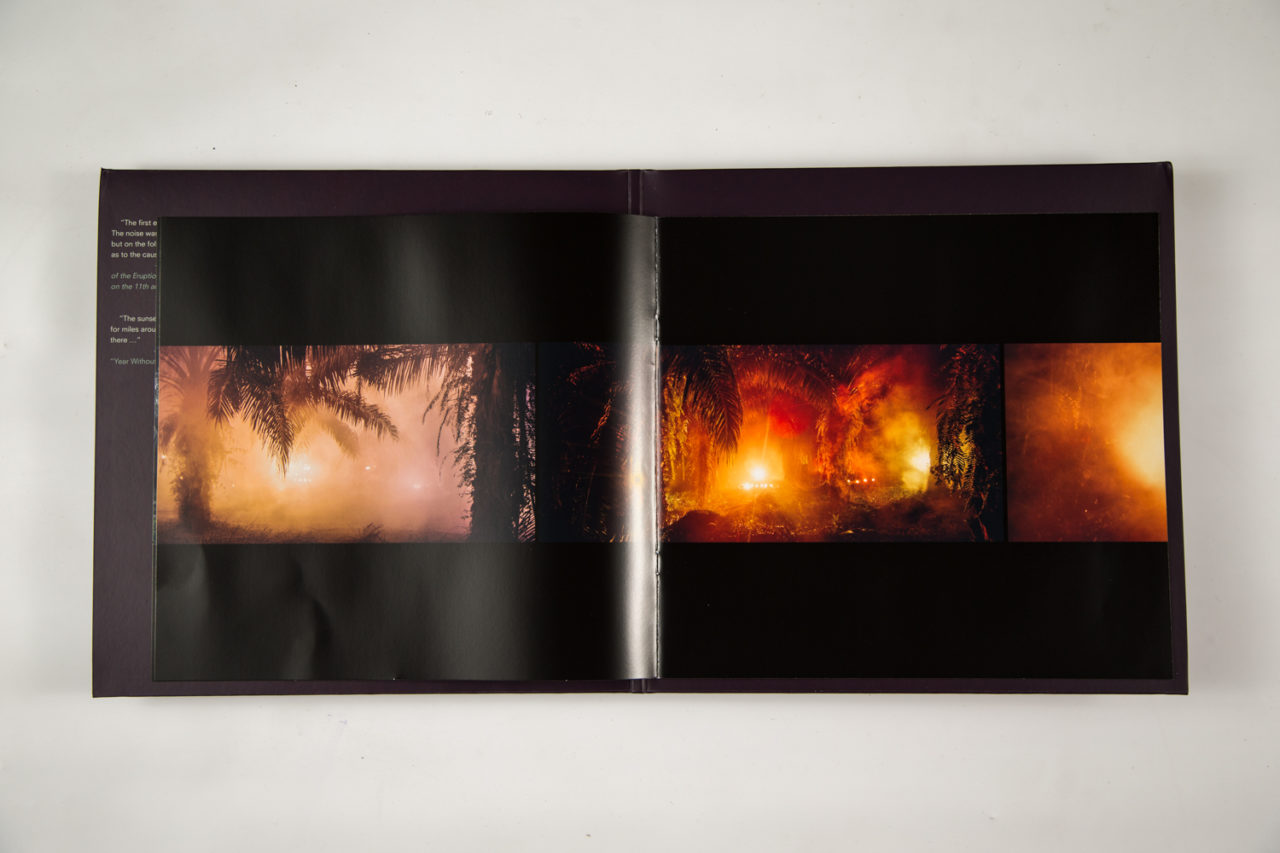

Its vinyl release also featured a 16-page book with striking photography and film stills. Taken alone, the album is singular. As a whole, An Invitation To Disappear soundtrack becomes far more than the sum of its parts: a world of crimson, emerald and indigo-hued jungle sounds and visions.

In collaboration with Berlinische Galerie, Berghain brought the album to life – with a special screening of An Invitation To Disappear with a live performance by Inland. The event coincided with the opening of Charrière’s solo exhibition As We Used to Float at Berlinische Galerie which runs until 8th April 2019.

Eager to find out how the project took shape, and transformed – from creative embers in the studio to film, score, vinyl and performance – we spoke with Charrière and Davenport to find out more.

What was your collaborative process like when working together on the sound design for An Invitation to Disappear?

Ed Davenport: It varied between me making sounds alone in my studio in direct response to the moods Julian had sent me (stills and short videos from his early visits to the site), and working with a plethora of field recordings from the plantation. When we had a rough collection of tracks or ‘chapters’ for the score, we sat together and decided which should go where and how things should develop. After the shoot was done, we went to Leipzig to work with Felix Deufel at Wisp Collective on the 32 point 3D sound mix for the gallery installation, which was first shown in April 2018 in Mainz.

Did this differ to your previous collaborations? If so, how?

ED: It was much more involved, and required a lot more test versions and drafts, than our previous collaborations. It was also on a much larger scale, as the installation is based on a 76-minute loop. There is at least another 60 minutes of unreleased music left after the final cut for both the gallery version and album, so it was a very creative process, which will no doubt feed into future releases as Inland too.

The album and soundtrack were created as a response to the 200th anniversary of the eruption of Indonesia’s Tambora volcano – Julian, how did you find out about the eruption?

Julian Charrière: In February 2017, I was a part of the first Antarctic Biennale wherein a group of fifty people, from artists to scientists and philosophers, were packed onto a Russian research ship for a two-week expedition from Argentina to Antarctica and back. It was the perfect time to explore that world, as I was in the beginning phases my project Towards No Earthly Pole, looking at rapidly changing frozen locales and other places greatly affected by climate change.

On that trip I met American philosopher Dehlia Hannah who was working on a book, A Year Without Winter, examining contemporary global climate change resulting from the actions of man as contrasted to the global climate change of 1816 resulting from the eruption of Mount Tambora. The connection between our two projects was serendipitous, especially considering that one of the places I was interested in filming, the Giétro Glacier in Switzerland, was majorly altered by the cooling effect from Tambora’s eruption, causing it to grow in size, creating a natural dam of sorts which would then melt away and cause a major flood as the global weather pattern returned to normal in the years following the Year Without Summer.

Was there a catalyst for wanting to create a video installation based on the eruption?

JC: What I figured was the next step for me in my research was to get on the ground and see where it all began by traveling to Mount Tambora with Dehlia. What we found along the journey was an endless grove of oil palms, stretching out in an unnatural grid that seemed to go on forever. This palm oil we had been consuming in our snacks all along the trip was a result of yearly fires burning through ancient forests in order to plant more oil palms, destroying significant carbon sinks and releasing it all into the atmosphere as Tambora itself had done just 200 years before. The parallels were uncanny, and I knew I had to do a project about this connection.

There was something so intrinsically cinematic about the emptiness of the plantations—a suspended reality amongst fronds and fruit—and it became clear that the project would be a film and accompanying photo series. As I had collaborated with Ed on so many of my films (and the later emerging idea of throwing a rave within the plantation to exacerbate the surreality of the place) it was only natural to bring him on board.

Why did you decide to recast the music from the video installation for the soundtrack (versus using the same music)?

ED: The music from the installation follows a very specific timeline, designed to draw the viewer into a rave state while surrounded by sound. It is continuous and for the most part features pumping four-to-the-floor versions of the tracks. We also worked intensely on creating the feeling of distance and space in the film soundtrack; you hear a sound system rumbling in the jungle, at first from very far away, with the trees, breeze and fauna interfering with its path to your ears. We all agreed that the LP version should be a more classic album listening experience, and the two sides of the project should stay clearly in their own worlds.

How did you approach transforming the soundtrack from Julian’s video installation into the tracks for this album?

ED: It was a natural process as I always save multiple versions of tracks and projects. I went through and began stripping back some of the more overpowering kick drums and in places adjusting the tempo of tracks to help add some variation and structure to the flow. I love the process of re-mixing my own music and have become so accustomed to working like this that it was a really fun process. Alex Samuels, the label manager at Ostgut Ton / A-TON, was also instrumental in choosing and structuring the final track order.

Was it important for you have a physical release of this music? If so, why?

ED: Even in this digital age, a physical record with lovingly curated artwork and packaging holds so much value. Also given the context of this project, and with Julian’s involvement, we really wanted to have a heavyweight, collectable object to hold in your hands – like a book or an art edition. The high-end printing, the layout and the texture of the paper all add to the experience.

Does the design of the 2xLP tell a different story to the film?

ED: It’s an archive-hybrid of the project, presented as a music album, so it’s a record first and foremost. The story, or the setting, is more mysterious, but I think it still very much draws you in. When you walk into the gallery installation or the live performance of the film, it’s clear that it’s a multi-sensory experience. The show at Berghain got really trippy and became this bizarre mixture of art performance, techno-rave and film screening. So the LP is like an artefact of this. You can own it and experience it by itself, or if you’ve witnessed the film in person then it becomes a piece of evidence or archive of the event.

How did you create the images in the book?

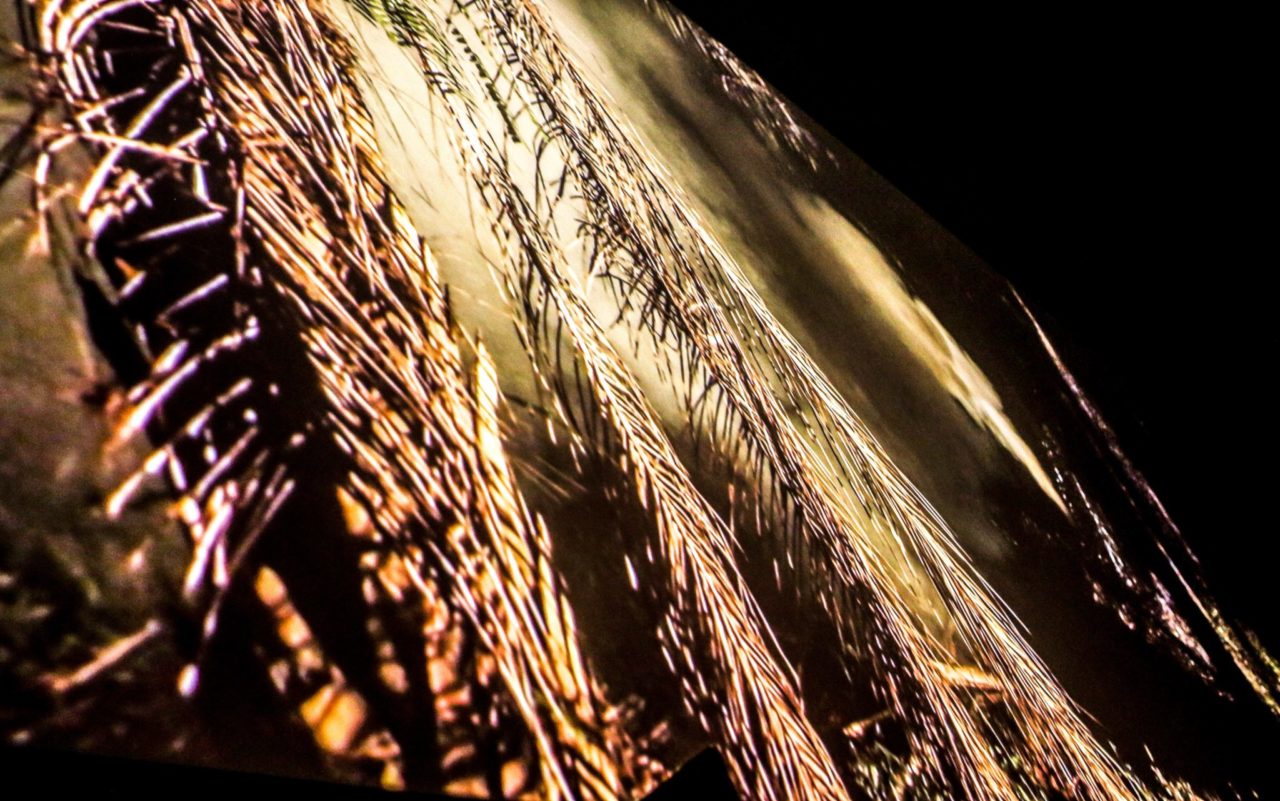

JC: The pictures are photographs as well as stills from the film. In the aftermath of Tambora’s eruption, particles were distributed into the atmosphere, creating a unique diffusion of light in the twilight hours that European painters like JMW Turner and Caspar David Friedrich dutifully captured. With the rave equipment of fog machines and strobe lights, I recreated that ambient, picturesque quality which has come to epitomise the sublimity of Romantic painting. In the booklet, you will find some photographs directly related to that aesthetic cosmos, as well as a sort of storyboard which gives a visual idea of the chronological progression of the video.

How does the dance floor relate to apocalyptic Indonesian tropics?

JC: Electronic music like techno, based on repetitive beats featuring polyrhythmic structures, is a direct relative of indigenous, shamanic, tribal and transcendental music – a language of rhythm understood worldwide. This tribal music and the whole cosmos of the ritual of dance is strongly bound with nature and the forest. Those ancient sacred forests are of course now disappearing in Indonesia, causing great disturbance and suffering to its indigenous population.

To juxtapose this was really interesting to me. The canopies of the jungle mirror the high arching ceilings of Europe’s cathedrals and churches – for many the modern day place of ‘worship’ is now the club. All this combined with the introduction of a popular Western subculture into the highly cultivated space of a post-colonial oil palm plantation proposes a lot of questions and begs further investigation.

ED: The dance floor is a gateway to another state. That state varies greatly for every dancer, but setting foot on the floor, joining the dance and becoming part of the crowd has a powerful effect that is more and more valuable nowadays. I really think it’s become a powerful form of post-modern therapy. The music at the epicentre of this can be so intoxicating and incredibly diverse, its dizzying.

New strains appear every day, strange new forms and secretive creators – hybrids and micro-genres – all on a global scale disseminated via the internet. It’s a powerful monoculture that mirrors industry, technology (agriculture – genetic engineering) and humanity’s forward quest, as it constantly looks to the future for new ways to connect, to inform and grow. The idea of these vast palm plantations in Indonesia being the venue for a rave is a spooky, futuristic and wonderfully dystopian concept that proposes the juxtaposition of hedonism (an escape, wild abandon, rave-states) and man’s blatant shortsightedness and greed when it comes to the destruction of nature for short-term gain.

Julian Charrière’s solo exhibition As We Used to Float runs through 8th April at Berlinische Galerie.

An Invitation To Disappear is out now on A-TON.

All live photography: © Votos-Roland Owsnitzki. Taken during An Invitation To Disappear A/V performance & projection at Berghain. An Invitation To Disappear, 2018, Single-channel video installation, 4k colour film, Ambisonics-soundscape

Additional images by Elina Abidin for The Vinyl Factory.