Published on

August 11, 2017

Category

Features

The vibes master.

To call Roy Ayers a crossover artist is technically accurate, but at some point it’s worth asking where he wound up crossing to, and where the line he crossed even stood in the first place. A prodigious jazz talent raised in a musical Los Angeles household, he was literally handed a set of vibraphone mallets by great master of the instrument Lionel Hampton at age five. By his early twenties Ayers went from his recorded debut as a sideman to the headliner of his own album within a year.

While his work in the 1960s was distinguished in itself – he became a vital part of Herbie Mann’s band late in the decade, and had a fine run of releases on Atlantic around the same time – it was in the ’70s that he really began to flourish, establishing the eclectic ear that would make him a commercial smash for much of the decade and an inspiration to house, hip-hop, and acid jazz artists for decades afterwards.

How Ayers pulled this off is a somewhat contentious matter: after forming Roy Ayers Ubiquity in 1970, he fearlessly explored the connections between jazz and R&B in all its forms, from singer-songwriter soul to deep funk to sweaty, hedonistic disco. Naturally, this was anathema to jazz traditionalists, who found the ’70s and its wave of jazzbos going funky a real rough patch. By the end of the decade his total disco immersion was greeted with apprehension at best by critics despite his flourishing commercially.

Time, it turns out, had other ideas: all those Roy Ayers Ubiquity LPs that had fallen out of print by the ’90s had become hot commodities for producers and other crate diggers who found both heavy motion and nuanced beauty in those records. Ayers became a revered icon in hip-hop and R&B circles across generations – from collaborating with Guru and The Roots in the early-mid ’90s to Erykah Badu and Marley Marl in the early ’00s to Tyler, the Creator just a few years back. The influence his music has left has grown even broader than the influence of the music he took in, and these ten albums should give you a good notion of how that happened.

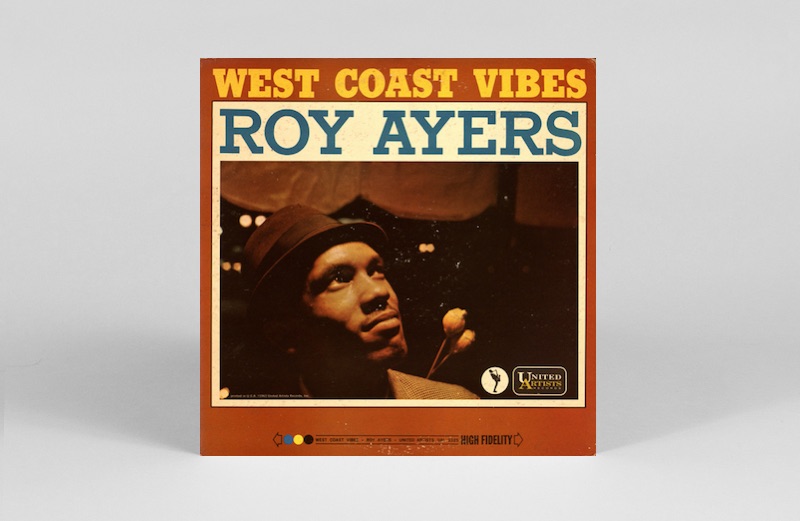

Roy Ayers

West Coast Vibes

(United Artists records, 1963)

To get a better understanding of Roy Ayers as the soul-jazz crossover star he was in the ’70s, it’s helpful – and fairly fascinating – to hear him in the more traditional jazz setting he came into as a youngster. The 1962-63 sessions that led to Ayers’ first top-billed album West Coast Vibes have him already in top form as a soloist, slinging the percussively melodic qualities of his vibraphone playing through a handful of standards that he already sounds comfortable running headlong through fearlessly – a carefree demi-bossa ‘Days of Wine and Roses,’ Charlie Parker’s ‘Donna Lee’ hopped-up and rolling, a giddy light-speed sprint through Thelonious Monk’s ‘Well You Needn’t’. He’s not quite the fusion-bound auteur he’d grow into within ten years, but as a young lion of bop it’s easy to hear him as a potential heir to Lionel Hampton.

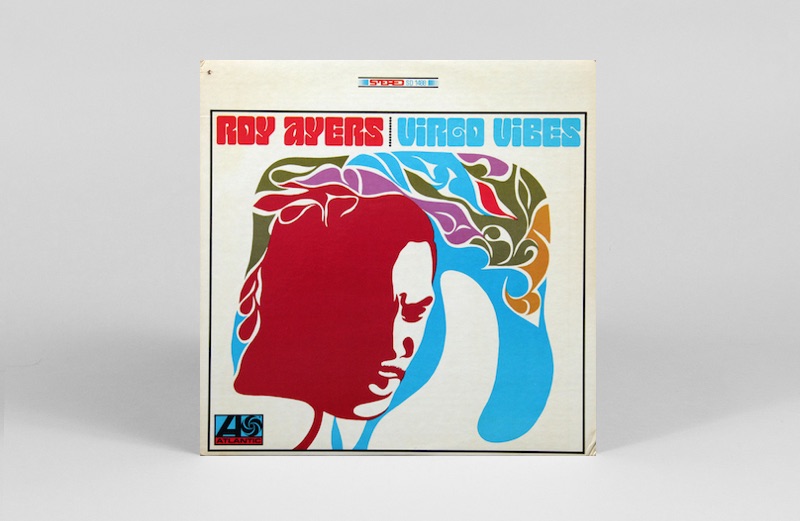

Roy Ayers

Virgo Vibes

(Atlantic, 1967)

Within a few years of his bandleader debut, Ayers had quickly immersed himself in the midst of something more sprawling and ambitiously daring than the trad-bop he’d made his first breakthrough with. As the second release with Ayers as leader and a high point of his late ’60s stint on Atlantic, Virgo Vibes hints at deeper, more loose-flowing ideas from its psychedelic cover on down.

The personnel on side A – including tenor sax great Joe Henderson, longtime Herbie Mann drummer Bruno Carr, and a one-and-done piano player named Ronnie Clark (who debuted on and subsequently retired after this album in pursuit of his day job of being Herbie Hancock) – shine on a front-loaded itinerary of frantic post-bop (‘The Ringer’), punchy samba (‘Ayerloom’), and a sharp-edged difference-splitter between the two (‘In the Limelight’).

Flip the LP over, and you get a sextet in repose, though no less energetic. The bluesy title cut’s downtempo nature just leaves even more room for Ayers’ melodic runs to find every point of entry in and out of the rhythm, and the majestically looming ‘Glow Flower’ features some spectacular interplay between Ayers and Jimmy Smith Trio veteran drummer Donald “Duck” Bailey.

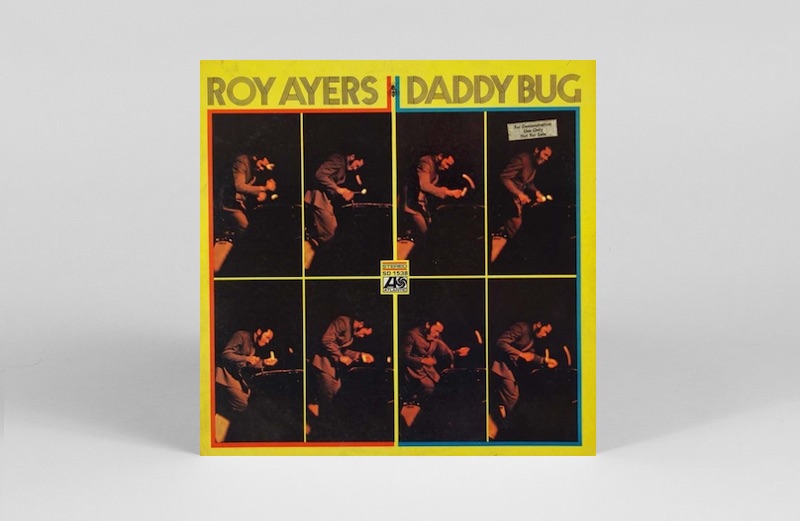

Roy Ayers

Daddy Bug

(Atlantic, 1969)

This album might be one of Ayers’ shortest, or at least feel like it – all eight tracks are under five minutes – but don’t mistake that for a lack of ideas. As the ’70s and a career of funk/R&B crossover loomed, Daddy Bug could be considered one of Ayers’ last great flings with a more traditional wave of jazz. That said, the stylistic flourishes on this one still lean in their own unpredictable directions, from William S. Fischer’s cool-breeze arrangements to Ayers’ choice in material.

When he directs his band through ballads, he cuts out the easy listening chaff and finds the strangely elegiac in Bacharach/David’s standby ‘This Guy’s In Love With You,’ and he finds three different ways through bossa – wistfully romantic, elegantly serene, and coolly sophisticated – on a trio of Antonio Carlos Jobim selections in ‘Bonita,’ ‘Look to the Sky,’ and ‘It Could Only Happen With You’. A take on Laura Nyro’s ‘Emmie’, featuring Ayers’ vibraphone taking on an expressive, almost lead vocal tone, prefigures his later work reinterpreting (and writing) contemporary pop, while his jittery fifty-note-samba title cut and the window-misting noir jazz of ‘Shadows’ indulge his future tendencies to find the more uncanny traits of otherwise familiar styles. A version without the overdubbed strings and woodwinds was released seven years later as Daddy Bug & Friends, but go for the original, it’s a fair stretch weirder.

Roy Ayers Ubiquity

He’s Coming

(Polydor, 1972)

It’s impossible to overstate the impact that Roy Ayers’ 1970s output had on hip-hop: not only were countless moments from his discography sampled by producers from the early ’90s to today, even his album art was paid homage when Smif-n-Wessun’s 1995 debut Dah Shinin’ modelled itself off He’s Coming, the first LP credited to Roy Ayers Ubiquity.

Ayers’ albums became hip-hop fodder for a few obvious reasons, not the least of which was his ability to arrange hard-hitting or otherwise prominent rhythms with almost eerily haunting melodic themes. It was all a strong ensemble effort, of course: Harry Whitaker needed just two chords to launch one of the most indelible anthems of its or the succeeding generations time in ‘We Live in Brooklyn, Baby,’ a song the band built off the simplest of refrains into arguably the most stirring jazz-funk song ever recorded. (Selwart Clarke’s angelic/suspenseful string arrangements, Bob Fusco’s nervy chicken-scratch guitar, and Ron Carter’s brilliantly nuanced performance on bass have a lot to do with that, too.)

Black Moon, Mos Def, and Kendrick Lamar all delivered career highlights over pieces of ‘Brooklyn,’ but there are less-famous, equally striking highlights, too: cosmic prog-gospel-funk opener ‘He’s a Superstar’ makes Jesus sound like Shaft and outdoes Sir Andrew Lloyd Webber at his own pop-songs-for-Christ game. Closer ‘Fire Weaver’ is the kind of propulsive orchestral jazz-funk that made his gig doing the film score to blaxploitation classic Coffy a given, and the jauntily chaotic post-boogaloo of the title cut is a joyful culmination of all the bossa and samba influence he’d waded through over the previous several years.

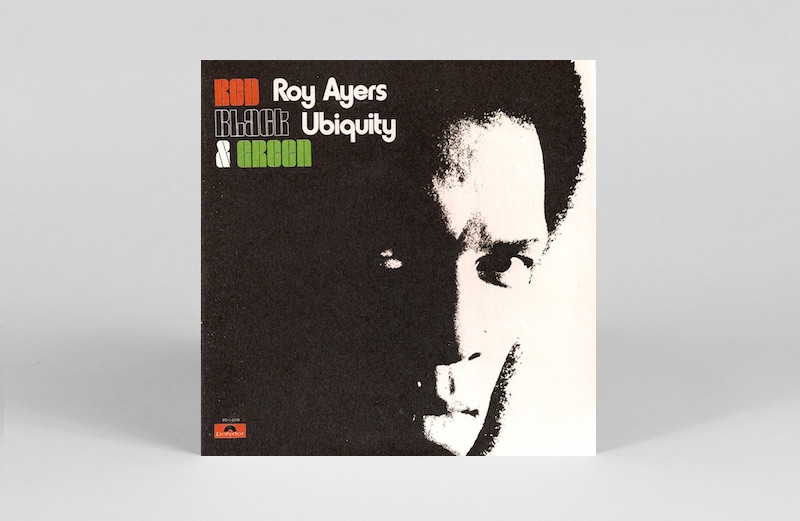

Roy Ayers Ubiquity

Red, Black & Green

(Polydor, 1973)

By the early ’70s, jazz musicians from Rahsaan Roland Kirk to Grover Washington, Jr. to Grant Green were filling their albums with bold reinterpretations of contemporary pop and R&B songs, but few of them hit the sort of trifecta Roy Ayers Ubiquity nailed on Red, Black & Green.

Bookended by a slick but brooding version of Bill Withers’ ‘Ain’t No Sunshine’ and a staggeringly funky take on the Norman Whitfield/Barrett Strong classic ‘Papa Was a Rolling Stone,’ with a glimmering ether frolic through Aretha Franklin’s ‘Day Dreaming’ dropped in to close side A, Ayers’ improv-heavy yet pop-hook-tight ensemble picked up where He’s Coming left off. It made his soul-jazz bonafides powerful enough to go toe-to-toe with whatever the great songwriters and arrangers of soul could concoct at their peaks.

The album also features some of his most unapologetically heavy-funk-skewing material, from the title track’s black liberation anthem to the joint-dislocating groove of ‘Cocoa Butter’. Of particular note is the spectacular rhythmic rapport between Ayers’ solos and the drumming of Dennis Davis – the latter providing a beat that could roll out an entire avalanche on the one, as also heard later in the decade sitting behind the kit for David Bowie from Young Americans through Scary Monsters.

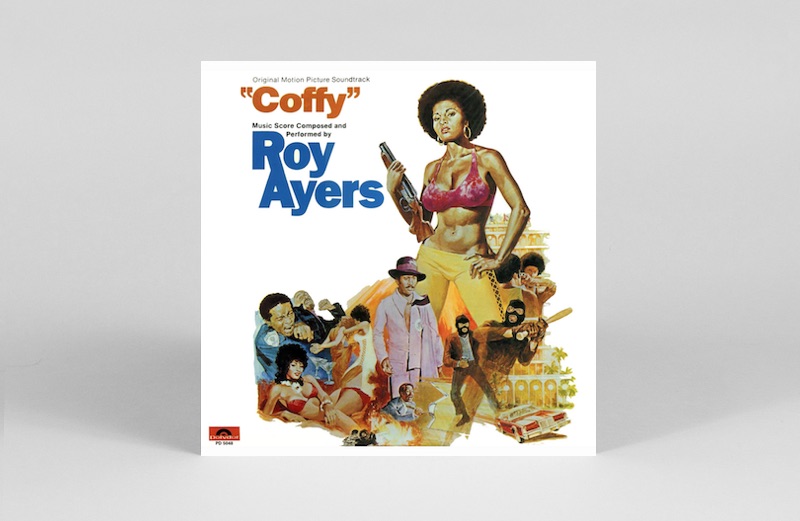

Roy Ayers

Coffy

(Polydor, 1973)

Roy Ayers’ only soundtrack might be one of his best-loved albums, and not just for its attachment to the movie that made Pam Grier an action superstar. Using much of the same personnel as his previous Ubiquity records – along with guest appearances by on-the-come-up jazz singer Dee Dee Bridgewater – Ayers cut both classic songs and memorable cues for a record that feels like a concentrated, rapid-fire dose of everything he’d built since the beginning of the decade.

Theme song ‘Coffy Is the Color’ features an all-time great blaxploitation lyric (“Coffy is the color of your skin/Coffy is the world you live in”) and the dizzying whirl of one of Ayers’ greatest riffs, ‘Aragon’ is a three-minute instrumental that manages to be both bruising and sophisticated (with a mother of a Harry Whitaker organ performance and a top-that-Isaac-Hayes horn section), and the borderline schmaltz of ‘Coffy Baby’ is entirely redeemed by a gutsy to-the-rafters Bridgewater lead vocal that made her Tony-winning stage career a foregone conclusion. And don’t overlook the shorter cues, where Ayers and company let some of their more strikingly unusual tendencies to the fore, like the haunting kaleidoscopic euphoria turned sinister of ‘Coffy Sauna,’ the percussive intricacy and disorienting horn charts of ‘Escape,’ the giallo harpsichords on ‘Vittroni’s Theme: King Is Dead,’ and the death-by-free jazz of ‘End of Sugarman’.

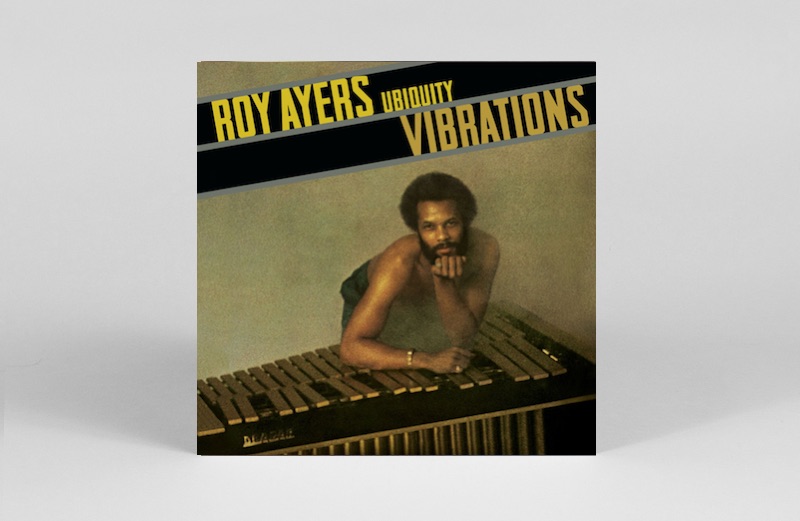

Roy Ayers Ubiquity

Vibrations

(Polydor, 1976)

By the second half of the decade, Ayers’ line-toeing between jazz and soul had become increasingly focused on the latter, and Vibrations marked the first of a trilogy of records that solidified him as arguably the decade’s most successful conversions to smooth R&B and disco.

If that had its own pitfalls – the purists came down on him hard, and frothy moments like ‘Baby I Need Your Love’ and ‘Better Days’ don’t help Ayers’ case much – its peaks were spectacular, and when the band locks in tight here it’s damn near impossible to not get swept away with them.

Songwriters, arrangers, and frequent collaborators Edwin Birdsong and William Allen encouraged a sort of prog-funk intermingling that session keyboardist and synth player Philip Woo tweaked into cosmic shape. And even as Ayers became more focused on his role as a lead singer than a vibraphonist, he maintained his knack for crafting these deeply wistful melodies that made mid-tempo cuts like ‘The Memory,’ ‘Searching,’ and the title cut some of his most resonantly emotion-stirring songs. it’s probably why so many producers, including Ant Banks (Spice 1’s ‘Face of a Desperate Man’), MF DOOM (‘Bergamot Wild’), and Pete Rock (‘Searching,’ with C.L. Smooth), used them to lace some of their best deep cuts.

Roy Ayers Ubiquity

Everybody Loves the Sunshine

(Polydor, 1976)

Speaking of samples. If any producer worth their SP-1200 owned only one Roy Ayers record, it was this one, and largely on the basis of that transcendent title cut. ‘Everybody Loves the Sunshine’ is something of a golden age outlier in that its frequent use in hip-hop wasn’t centred around a big drum break, but a number of melodic refrains – something that, in 1994, both a Mary J. Blige ballad (‘My Life’) and a Common boom-bap track (‘Book of Life’) could draw inspiration from.

From front to back, Everybody Loves the Sunshine may be Roy Ayers Ubiquity’s most joyous record, well before you flip the LP over and make your way to the title cut. The heavily soul-indebted, disco-friendly atmosphere grows effusive energy through deep grooves that get plenty of space to build, and though the jazz traditions of his early ’70s albums are even further in the background, the opportunities where he lets the players play – building ‘It Ain’t Your Sign It’s Your Mind’ around a Latin futurist rhythm where congas meet synths, or transmutating his vibe solos into a seamless electric piano on ‘The Golden Rod’ – highlight his ability to translate those instincts into something closer to R&B. A summer block party must-have.

Roy Ayers

‘Running Away’ 12″

(Polydor, 1977)

Lifeline, the last album to be credited to Roy Ayers Ubiquity, came close to signalling the point where a potential late ’70s creative slump threatened to set in. But as luck would have it, it also gave us possibly his best single of the decade’s second half, and easily one of the greatest 12″ extended singles to emerge from any soul-jazz artist to hear the siren call of disco.

Thanks to a bassline/guitar riff that still sounded floor-filling when A Tribe Called Quest sampled it for ‘Definition of a Fool’ 13 years later, ‘Running Away’ felt more at home in the cognoscenti crates of Larry Levan than it did in leisure suit suburbia, a cut that sounds every bit as Brooklyn as their we’re-tryin’-to-make-it-baby anthem of five years previous.

If a groove was all it was – and with a momentum this monumental, would you blame anyone for thinking a groove would be all it needed – ‘Running Away’ would be a worldbeater. But it’s the singers that sell it, as simple as the lyrics are. It’s a vocal sparring session between co-writer Edwin Birdsong, under-heralded jazz session singers Marguerite Arthurton and Sylvia Cox, and Ayers, whose matter-of-fact voice was never better suited for anything than it was for confronting a building “we don’t love each other like we used to do” ennui. Few songs about losing the spark in your relationship were ever this danceable.

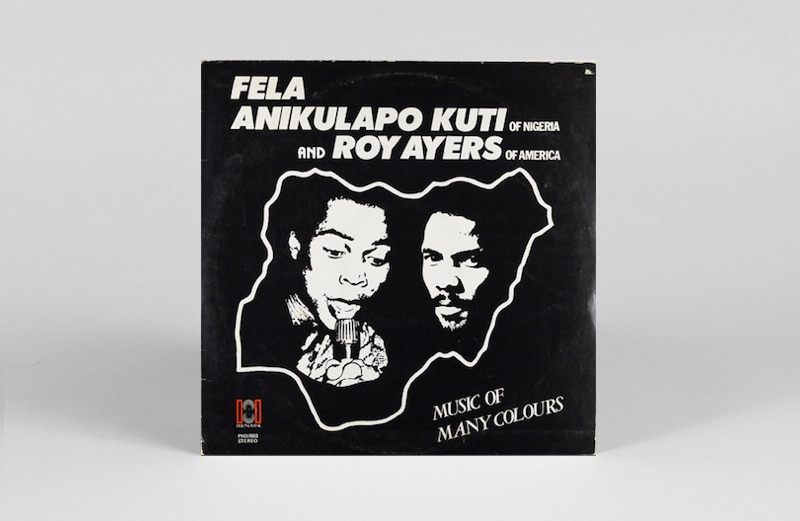

Roy Ayers and fela Kuti

Music of Many Colours

(Phonodisk, 1980)

Roy Ayers and Fela Kuti had drastically different 1979s, to put it mildly. Ayers had spent the year recording two albums, Fever and No Stranger to Love, that were his glossiest, most radio-ready yet, all disco flash and quiet storm simmer for better and for worse. Fela, meanwhile, was still reeling from the 1977 death of his mother at the hands of Nigerian government soldiers attacking and destroying his Kalakuta Republic studio/commune, and recorded Unknown Soldier, the cathartic album-length recollection of that night’s horrifying events.

But as the decade turned, Ayers took the opportunity to go on tour with Fela in Africa, a revelatory experience that Ayers stated would “be affecting my music in ways perhaps I don’t even understand yet” in a letter to the Indianapolis Recorder. That experience would be borne out further during the sessions that resulted in 1981’s Africa, Center Of The World LP, but it was Music of Many Colours, the album that Ayers and Fela recorded together at Nigeria’s Phonodisk Studio in the wake of that tour which really stands out as an epiphany.

Hearing Ayers chime his way through the rippling lope of the Afrika 70’s afrobeat stride as Fela breaks down colonialism’s obscuring of African history on ‘Africa – Centre of the World’ is a trip in itself, but the way he not just seamlessly but audaciously resonates and harmonizes with the rest of the band makes it legitimately staggering. Ayers takes lead vocals on flipside ‘2,000 Blacks Got to Be Free,’ a cut that owes more to his own uptempo disco-jazz sound, but his time steeped in the musical culture of Nigeria – with the greatest band the country and possibly the continent ever produced – he sands the gloss away to reveal the searing heat in the grooves beneath for more than 18 ½ minutes.