Published on

October 11, 2017

Category

Features

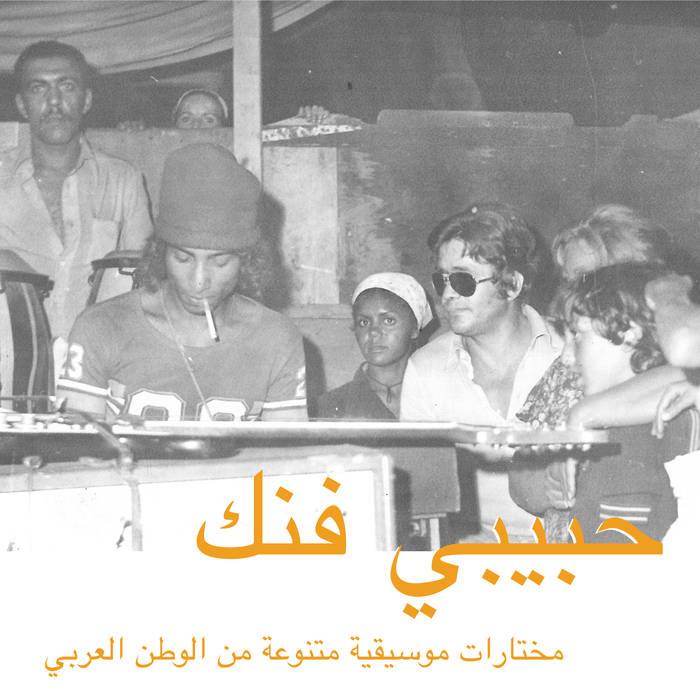

One of a handful of labels focussed on reissuing music from across the Arab Peninsula, Jannis Stürtz shares his stories from years of searching for the region’s funkiest records.

“I don’t have a blueprint, really,” says Jannis Stürtz when asked how he discovers records to release on Habibi Funk, his reissue label for ’60s – ’80s funk and soul music from the Arab world. Alonsgide running his other label, Jakarta Records (with releases from artists like Mura Masa and Kaytranada), and DJing around the world, Stürtz still finds the time to dig for records in “most [Arab] countries that you can currently go to” outside of the Arabic Peninsula.

Sturtz also snuck in some much needed time researching a forthcoming Habibi Funk issue, during a trip to Lebanon for the country’s first Boiler Room. “We are working on a release by a band from Lebanon in the 1970s. The guy has a hundred old videotapes and we’re still in the process of trying to find the tape reels for the release we want to do. He is very sparse with the information he puts on the tapes, so it’s kind of like searching for a needle in a haystack. He also doesn’t have a reel-to-reel machine. I don’t know anyone in Beirut that has one, so I always pick up a handful, digitalize them here in Berlin, and then return them again.”

Stürtz is well aware that the technological difficulties he encountered in Beirut can end up prolonging reissue projects. In fact, delays are a common thread in his work with Habibi Funk – whether caused by technological difficulties or for ethical reasons: “If you’re a European or Western label and you’re dealing with non-European artists’ music, there’s obviously a special responsibility to make sure you don’t reproduce historic economic patterns of exploitation, which is the number one thing when it comes to the post-colonial aspect of what we are doing,” he explains.

“At some point you have to stand up for licensing policies and privileges, because there will be people who call you out on it and we’re working in a setting where these topics matter.”

Stürtz sees theses ethical responsibilities in relation to Habibi Funk’s immense popularity in the Arab world, noting that “On Facebook, at least for the most important posts, we try to translate them into Arabic as well. Not because I think that the people who follow us from the region don’t also speak English. It’s more of a symbolic thing, communicating in a way that is inclusive.”

“Once or twice a month I’m lucky enough to take a trip to the region for DJ gigs, and I always try to find out what I can do on top of that. For [a recent trip to] Sudan, for example, it was just about trying to get into the Sudanese scene to learn about its musical history,” says Stürtz, who secured the help of a team of music-savvy locals.

Despite that local knowledge, Stürtz still found it extremely difficult to find recordings for Habibi Funk. Only a handful of Sudanese record labels released vinyl, and much of that did not have the characteristic “westernised, soul, funk and jazz-influenced sound,” he seeks out for Habibi Funk. According to Stürtz, “the way the system was set up in Sudan was that radio was not allowed to play vinyl records that were manufactured by the labels, because they assumed that if a record was played on the radio, nobody would go and buy it. They didn’t consider radio as something they could use for PR.”

Kamal Keila, who will be reissued by Habibi Funk in 2018

In fact, in Stürtz’s experience, to buy records in Sudan, you have to seek out a single person who has monopolized the whole industry. “[In] Sudan, there’s only this one old label that is run by this guy who has got be a millionaire, he’s got a lot of different business endeavours. The label’s called Munsphone and you have to sit around for hours for him until he decides whether or not he will let you buy some records.”

In Somalia, on the other hand, Stürtz ran into a radically different problem, where many radio archives were destroyed by political and religious extremist group al-Shabaab. According to Stürtz though, one of the radio archives did survive.

“There’s so much great music coming out in Somalia. Somali music from the ’80s sounds a lot like drum machines, computers and synthesizers, so it’s incredible stuff.”

Back in Lebanon, you can find shops run by old musicians. “In Beirut I came upon a little shop that sells old stuff – not even antiques – and this shopkeeper had a little stash of records with a 7″ among them by a band called The Souls. A band called The Souls from Lebanon sounded like something I’d be interested in, so I asked the guy about it and it turns out he was the drummer in the band in ’76 and he still had these 2 copies lying around ever since. When I visited again to drink coffee with him, he actually showed me a basement below the shop where he still has a drum-kit set up, and his own little bar where he mixes his own drinks.”

Egypt, a pop cultural mecca for the Arab world in the ’70s, is by far Stürtz’s favourite country to find records: “There’s this island in the middle [of Cairo] which is called Zamalek which has four shops that sell vinyl. Funnily enough, half of the shopkeepers are female — it’s the highest ratio of female record shop owners I’ve ever seen. No other city on this planet comes close.”

The shops in Zamalek are also a great source for new records: “It doesn’t feel like you’re always looking at the same records over and over again, there’s always new stuff or stuff you’ve never heard of.”

Rather than make general statements on vinyl trends in each of the various countries he’s visited, Stürtz instead offers a “micro-analysis” based on “personal interactions”. “Let’s take Al Massrieen, the Egyptian band which we reissued very recently. Their first album was from ’78 and the country had already stopped producing vinyl, so all their albums were just on cassette tapes. Whereas, for example, in Lebanon, records were pressed on vinyl until the late ’80s. This transitional period was very different in each country.”

That’s not to say that young people in Arab countries are not returning to vinyl too. “When I play a DJ gig, I have young guys and girls coming to me saying, ‘Oh yeah, I went to this record store,’ and I usually also receive Facebook messages from people saying ‘I found this record in my dad’s basement, do you know this one?’”

“This certainly doesn’t mean that buying vinyl is as common there as it is around here. To start with, finding a working record player is already a challenge.” But it’s a rising scene and through mixes and rereleases, Stürtz sees a growing audience.

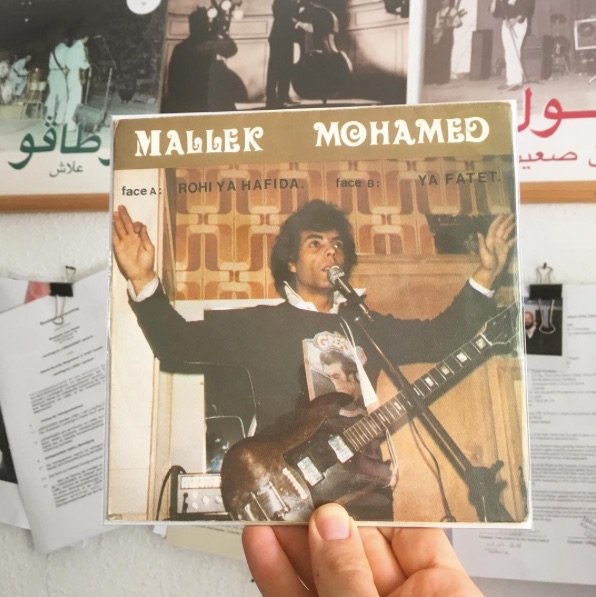

Mallek Mohamed, who will also be reissued by Habibi Funk in 2018

At the same time, however, Stürtz is quick to note that Habibi Funk’s sound, is “niche” and “specific” in comparison to both the historical and contemporary Arab music scene. He recognises that it is not an accurate representation of each region’s popular and historical music culture. Rather than reissuing records from Arab music and culture icons such as Egyptian singers Abdel Halim Hafez or Umm Kulthum records, instead, Habibi Funk’s reissues usually include a “disco reference”, operating more on Stürtz’s own musical taste and less so on traditional Arab music.

Stürtz admits that it is much easier to find more traditional music. “Let’s say the average shop in Casablanca has been sitting on old stock that was not sold in the ’60s and ’70s. They keep on selling it because a couple people went there with a similar music taste, but all of the stock that you and I may be interested in is gone. What is left is very traditional music, which is great, but is not my personal musical preference.”

His ultimate advice for finding records in these cities? Look for antique shops. “You get a feeling for shops that might not necessarily be record shops but also have some vinyl. Shops that have old books, shops that have old furniture. Basically shops that have stuff that they get from old apartments when someone dies, because they may have a stack of records.”

With that in mind, like Stürtz, you may be lucky enough to run into an undisclosed warehouse in Cairo, a retired ’70s Lebanese drummer with plenty of vinyl stashed away, or perhaps even a Sudanese billionaire, who will decide whether or not you can buy his records.

Habibi Funk 007: An eclectic selection of music from the Arab world features a collection of artists released or fortchoming on Habibi Funk and will be available on 1st December. Pre-order your copy and learn more here.