Published on

August 17, 2018

Category

Features

From East End blues parties to playing Plastics with Floating Points, Red Greg is a DJ who has only ever been motivated by a love for music. That his career has taken off at a (relatively) late stage is testament to the consistent quality of his sets, an ear for rare boogie and a gentle, unassuming demeanour.

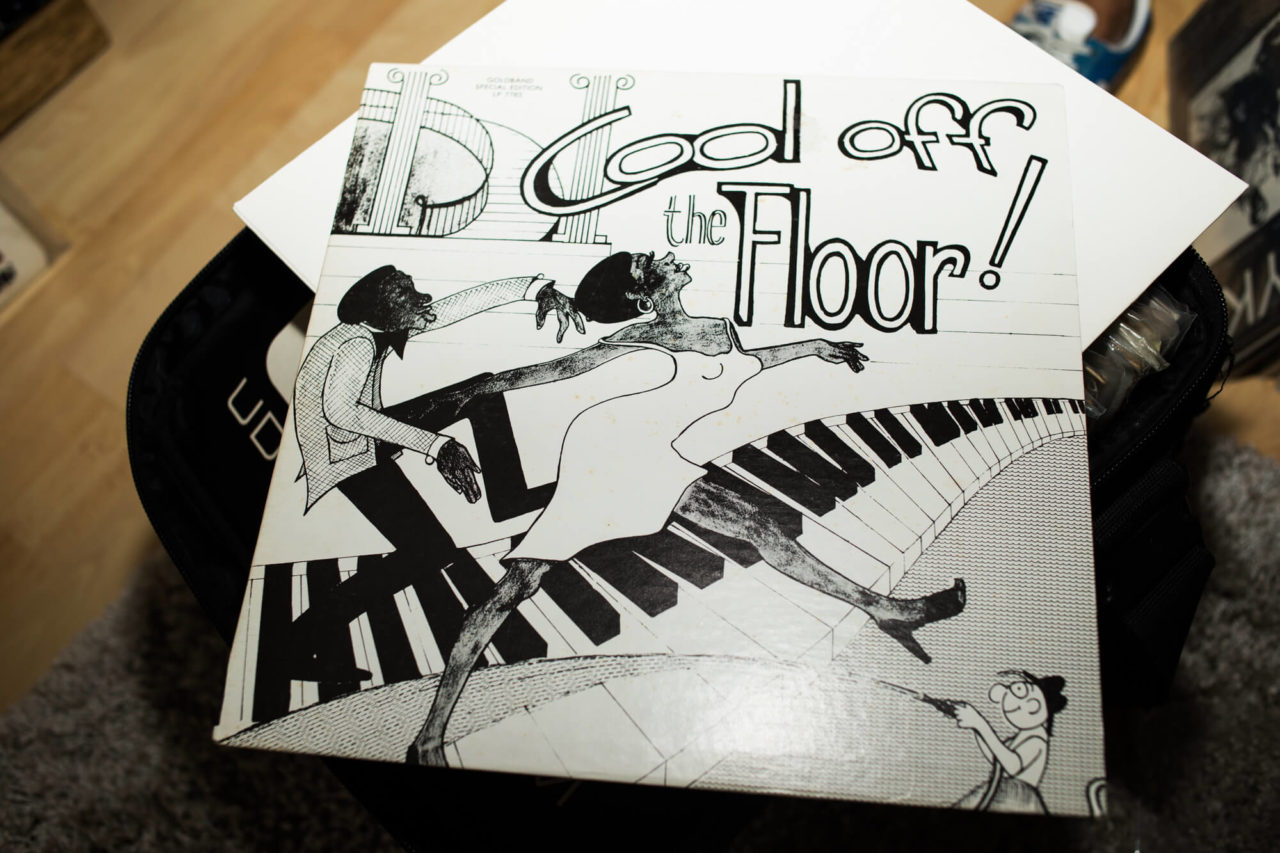

Darren Griffiths aka Red Greg lives in a small flat in Ilford with his partner and their Jack Russell, Arthur. For a DJ whose collection precedes him, the space is tidy, and besides an Expedit’s worth of records in the living room, you’d be forgiven for wondering what the fuss was all about. It’s here that we conducted the interview, as Griffiths tells of his teenage years at Funkadelic’s sound system blues parties in Canning Town, buying records from mail order pamphlets, and negotiating the cultural shift as 2-step parties were infiltrated by acid house in the early ’90s.

It’s not until the end of the interview that Griffiths suggests we see his albums collection in the bedroom, where records are perfectly stacked, floor-to-ceiling, covering its entire back wall. In the small corridor, he opens cupboards to either side, which are bursting with records. Every nook of this humble space is utilised. He assures us that most of his pop, RnB and house records are still at his mum’s.

Now in his late 40s, international acclaim has come later than most for Griffiths. A self-confessed ‘part-time’ DJ, he played the soul circuit in East London for almost thirty years before an email from Floating Points brought him into the You’re A Melody fold at Plastic People, the party and label, Melodies International, co-run by Mafalda, to which Griffiths now contributes regular edits, and a wealth of knowledge.

With an appearance at Dimensions Festival still to come this summer, Red Greg is revelling in playing records for open-minded audiences, and began by telling us about his own musical up-bringing, and how he’s managed to side-step the competitive, macho environment that surrounds the rare record scene.

An international DJ career has come a little later in life for you. When did that kick off and how has it been adapting to that?

I think it grew from the You’re A Melody parties. From that point, more people knew who I was. I had always been DJing, and the older people knew me, but Sam [Shepherd aka Floating Points] invited me down, and the younger people were really going for it, which was surprising to see for someone from my generation.

How did you first get to know Sam?

Just through records really. I think he got my email address off Richie [who runs Love On The Run parties] from New York. I got an email out of the blue from Sam asking, “Do you know this record or that record? Every time I Google them they come up on your mixes or on your compilations.” I met him at Plastic People and it all happened from there.

But you’ve obviously been involved in music for quite a while… None of this must have been that new for you?

Well, growing up in East London, Canning Town, I had two older sisters, and they’d go to a place called Bentley’s and other local clubs. My sisters would have mixtapes of local soul and reggae sound systems, and that’s how I got into music when I was about 14 or 15.

What was that local scene like?

The main sound system for me was Funkadelic, which was more a soul sound, and was run by George [Small] and Dennis [(Scanka) Lewis]. They were basically just blues parties, which would start at two in the morning and go until two in the afternoon in a flat like this… I think I went to my first blues party when I was about 15 or 16.

What did those blues parties look like?

They were basically like illegal parties, sometimes in a house that had been boarded up. They’d kick the door off, set up a bar, have drinks for £1. It was like an old warehouse party, but just really small. Usually they were free to get in, or something ridiculous like £2.

For me, there were a couple of songs that were important, one of which was Claussel ‘Let Me Love You’ and they’d play that. On a reggae sound system the bass was just incredible in a small place like this.

Literally in a flat this size?

Yeah, I remember one party got really rough because the neighbours weren’t happy. They came down with hammers and it wasn’t that nice. I think you had blues parties all over London, with all the different sound systems. There was Casual Affair, Side Effect, Mystery, Touch Of Class, Funkadelic… I was only 16 at the time, so I felt safe at the local East London parties in Canning Town and Forest Gate. I was more into the soul, but a lot would play reggae tunes. For me it was all about the 2-step, rare groove scene.

Were you buying records at that time?

I was always buying pop records as a kid. I’d go round my grandmother’s and she’d give me pocket money to spend on pop records at the shop down the road. When I was about 14 or 15, I got into the music that my sisters liked: Quincy Jones, and Evelyn King. It was only when I got into Funkadelic with a couple of friends that we wanted to set up our own sound system. We’d just left school and all chipped in and bought some equipment.

What was it called?

I think it was called Plus One because we were always adding one more person to the group. After that I started buying lots of records, things on West End, and also loads of 2-step. It was really different to now, because you’d just hear a jingle on the radio saying, “we’ve got these in stock”, and you’d go to Red Records in Brixton and find the rare ones. That’s how it all started. A couple of years later, there was a mail order company called Soul Bowl. You’d get the list through the door, see something you liked on the list, and you’d have to run to the phone and ask them to hold it for you, and send a cheque from the post office.

Real dedication…

Yeah, and at the time, not many people I knew were aware of albums by the likes of Milton Wright… I got that one from Soul Bowl, and everyone was surprised how I got that record.

A lot of those sound systems had a ‘selector’ as well as a ‘DJ’, but know they two terms have become somewhat conflated…

For me, I wanted to find my own records and play them. And at the time there were other sound systems like Rap Attack where it was all about mixing. For me, it was all about finding the records that other people weren’t playing and mixing, whereas with the more mature sound systems it was about having a selector and having a DJ, who would mix. There would be four people – the DJ, the selector, the MC, and the sound guy.

It was only a few years later that the whole acid house thing happened, so you’d be playing 2-step, rare groove, acid house, and reggae, at the same party, which was really good. It probably fizzled out in the ’90s, when house music was really predominant and it was more about mixing, but in the past ten years it’s gone full circle and it’s about selecting. You don’t have to mix, people can have a really good selection and you can just play your records.

Did you ever get into acid house?

Probably for about two years. Everyone would be on pills, and you’d be at a blues party where it was just 2-step, and then acid house – it was really weird, because some people just wanted to have a drink and dance to the music like before, and then all this new music came along, with people out of their heads, who just wanted it faster.

I was buying everything really. I was buying acid house and hip-hop, but I think all those records are at my mum’s house now. In the mid-’90s, I was into the RnB thing. I was buying records, doing some local DJ work, going to Black Market, or buying the New Jersey soulful garage imports religiously every week. There was so much going on musically and it was changing so quickly. It’s only been the last ten years that I’ve stuck to playing one thing, so people have been booking me to play disco and boogie.

Were you holding down another job throughout?

Yeah, buying records was always just been a hobby. I’ve never been a full-time DJ, I’m still not, really. The last ten years, I’ve worked in education, in provision for kids who’ve been kicked out of regular school, and now it’s just two days a week.

Do they know you’re a DJ in your spare time?

No, not really! No one would be interested…

You’d be surprised… You mentioned the Milton Wright records rearlier, but were there other things you got that other people were after?

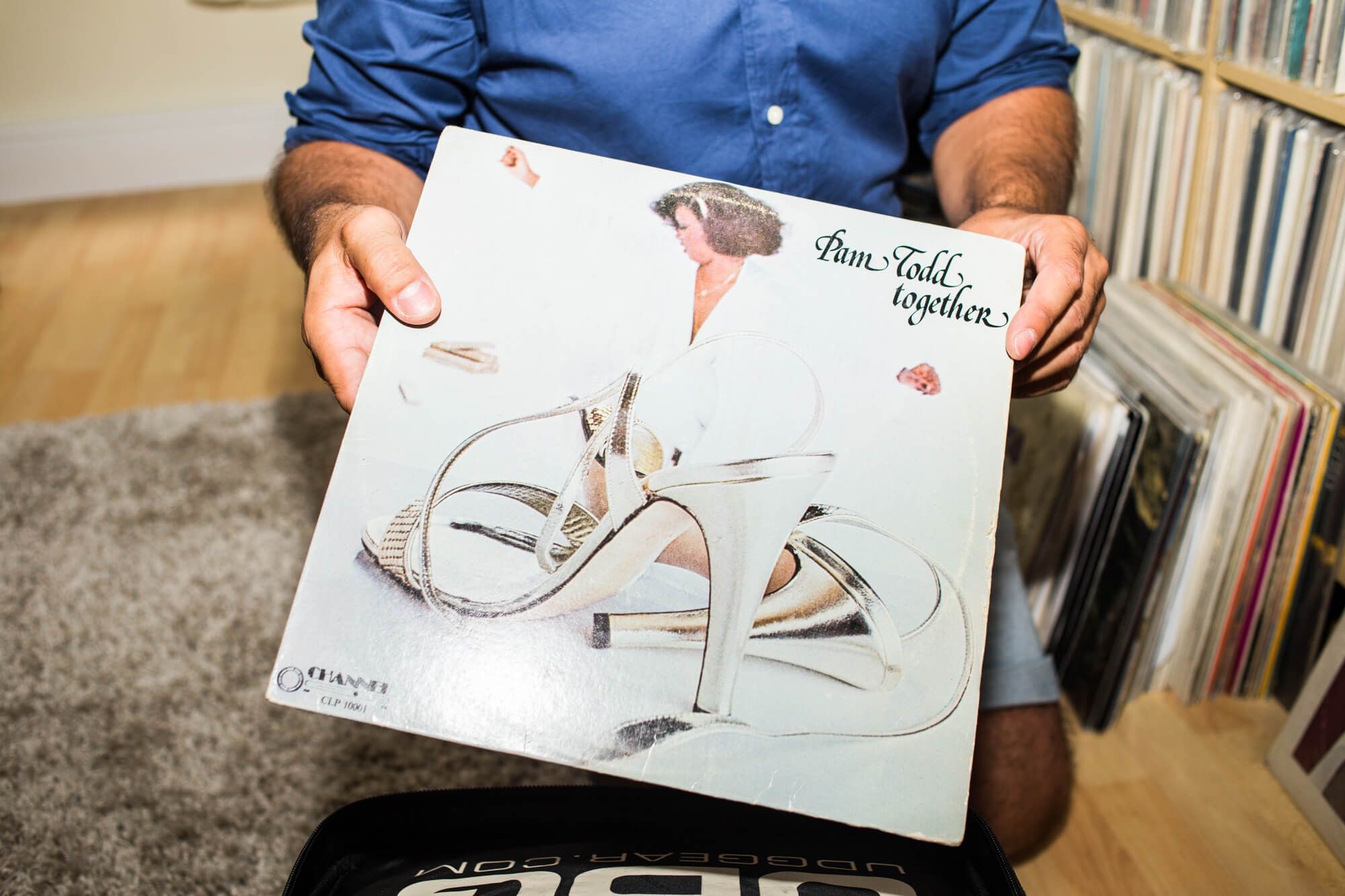

Yeah, there was Bobby Wilson – ‘Deeper and Deeper’ – a Barry White-esque thing that I would play at the end of the night. Also, things like Pam Todd ‘Let’s Get Together’ played a massive part in what I play now. I remember seeing it from Our Price in Stratford, and I think I got that there. So records like that are still really important.

Can you put your finger on what appeals to you when you first hear a new track that you like?

For me, the sound is instant, if it’s that whole optimistic, feel good, positive feel to it.

Were you ever much of a record dealer?

No, not really. I’m terrible, because if I see something I like I’ll buy it. Do you know Roy Ayers’ Silver Vibrations? It has got a long version of ‘Chicago’ on it, which is not on the US album, and I’d always see it for a fiver and I ended up with twenty copies over the years. It’s such a good record, why is nobody buying it? And then it started going for £150-£200…

Because you had them all!

Haha, maybe. I gave some of them to friends and sold a few… Most of the records I have in the other room are really cheap albums, but they’re just brilliant records. It’s not really about rarity for me, it’s more about the music. There are loads of mid-late’80s boogie records, for example, that people are going crazy about now, which at the time everyone would have said was no good compared to West End or Salsoul. But now because they’re expensive people really want them, and they’re not necessarily that good.

Sometimes with rare records people leave their ears at the door, so to speak…

Some people just want these trophies, and it’s very macho and competitive, which I really don’t like.

What’s your upper limit for buying records?

I always try to stick to £500. That’s probably about the most I’ve spent on a record. That’s a rarity really. Most of the stuff I like I manage to find before they go through the roof, which is good!

And you’d play this stuff out at a gig?

Yeah, although I know collectors and DJs who won’t play these records. That seems weird. They’re made to be enjoyed. I understand that people just want to put it on the wall and it’s all about keeping the value, but I’m pretty bad with playing them and stuffing them in the bag. I want to play them, I want to enjoy them, and I want people to enjoy them, that’s what it’s all about for me. It’s not the best when someone drops a drink on a £500 record, but that’s life.

I have also started getting into more unreleased acetates from the ’70s. I just try and collect the unreleased things, which there are not many of. This one by DeeDee Sharp, I played in Paris, and back-cued it once, and then when I pulled it forwards the first beat had been wiped, so I don’t play them anymore!

What’s your routine for putting a bag together for a gig?

I think I’m constantly turning stuff around. You’ll have your staple songs and everyone knows you for playing certain songs that they now expect, like the Fronzene Harris ‘Lifetime Guarantee’, which I played at Dekmental with Ge-Ology that someone took a video clip of…

Has it been a bit of a learning curve playing in these festival environments or to bigger audiences than before?

It’s been really good, and amazing to see young people sing along to records that are not mainstream. The Netherlands in general is just amazing for an open-minded young crowd. Even if they don’t know the music, they’ll dance for the full set, which I’ve never experienced before.

What does your collection mean to you as a whole?

It’s part of my life. At my mother’s house there are a mixture of big records from the ’80s and ’90s – loads of house stuff and dance stuff. I find it hard to get rid of them, because they take you back to that time, playing at this or that bar, and the people you were surrounded by then. It’s all part of my life.