Published on

March 22, 2017

Category

Features

Everything you need to know about the obsessive record producer behind era-defining records by Buzzcocks, Joy Division and Happy Mondays.

There are producers, and there are visionaries, manipulators and megalomaniacs posing as producers, who see commissions as chances to create music without the time-consuming task of writing and promoting it, riding slipshod over the artist’s desires, obsessively driven (crazy) by a sound seemingly only in their head. Producers such as Phil Spector, Joe Meek, Trevor Horn and Martin Hannett.

Typically, this style of producer brings baggage, often various degrees of tragedy, to complement their obsessive, blinkered personalities, triggering conflict, which in turn can trigger brilliant work or catastrophe (sometimes both). Hannett is a textbook case, creating legendary work between the late ‘70s and his last production in 1990, a year before dying, weighing 24 stone, aged 38, defeated by his addictions. But he left behind some of the most memorable, era-defining records in British history.

Hannett’s legacy is not just the music but the mechanics of making music, which a new book, Martin Hannett: His Equipment And Strawberry Studios, addresses directly. The author Chris Hewitt was behind Martin Hannett: Pleasures Of The Unknown and the DVD Martin Hannett: He wasn’t just the fifth member of Joy Division, but neither provide this kind of electronic geek porn, writ large on A4, a cornucopia of keyboards and computers, tape machines and devices with names such as the Ursa Major Space Station (a digital reverberator).

The man’s doodles also occupy whole pages, so in a sense, this is the most accurate portrayal of Hannett, and the kind of producers typically obsessed with machines to facilitate their vision, or open the door to something they didn’t know existed. And with each new machine, they plough on, taking more time, falling deeper into their obsession. Since Hannett began working in studios at the dawn of digital production, this process would dominate his life and the records he produced. But what was – is? – “the Manchester sound”? And how did Hannett get there?

Buzzcocks

Spiral Scratch

(New Hormones, 1977)

For a producer in the mould of Phil Spector, it’s fitting that Hannett was exposed, at fairgrounds in his native Manchester, to Spector’s towering sixties edifices. “I used to stand underneath those enormous Wharfdale speakers,” he recalled. “I was 11 years old.” Through his teenage pal CP Lee, whose cousin in the navy brought back hard-to-find imports, Hannett discovered rock music, especially loving “anything off the wall, because of the production,” Lee recalls. “When you listen to the first Doors album, recorded with Dolby, but played back without Dolby, compressed treble, incredible!” Hannett said.

Invariably stoned or tripping, in his long coat, scarf and curly mop like Manchester’s version of Tom Baker’s Doctor Who, Hannett worked as a lab chemist, a soundman and early production work for theatre. He also played bass for the short-lived Willy & The Zip Guns but stage nerves put paid to band ambitions, and he began promoting local bands and renting equipment. “Martin wanted musicians to control their own destinies, create their own gigs, make their own records,” said Lee.

Punk, therefore, was perfect timing. But Hannett wasn’t just thinking altruistically. As opposed to dealing with uppity musos, punk bands gave Martin the raw materials that he could manoeuvre and mould.

Inspired by The Sex Pistols, Manchester’s punk trailblazers knew Hannett through his occasional writing for the local New Manchester Review. Hannett’s company Music Force helped get Buzzcocks gigs, and when the band wanted to make their own record, the experienced, enthusiastic Hannett – or Martin Zero as he was then calling himself – was a natural ally. “In the control room, Martin was twiddling the knobs and faders, and as fast as he was doing it, the engineer was moving them back, saying ‘you can’t have that,'” recalls Buzzcocks frontman Peter Shelley. “He was already experimenting. It still surprises me know how alive and fresh Spiral Scratch sounds, and how perfectly it encapsulated Buzzcocks.”

Dry, direct, compact, surging, metallic: Spiral Scratch was powerful and authentic in the way that other punk records of the period weren’t. “When you play Spiral Scratch loud, it sounds exactly as if you’re right in front of the stage at one of their gigs,” Hannett subsequently said. “I was very disappointed when the Sex Pistols album came out with seventeen guitar overdubs.”

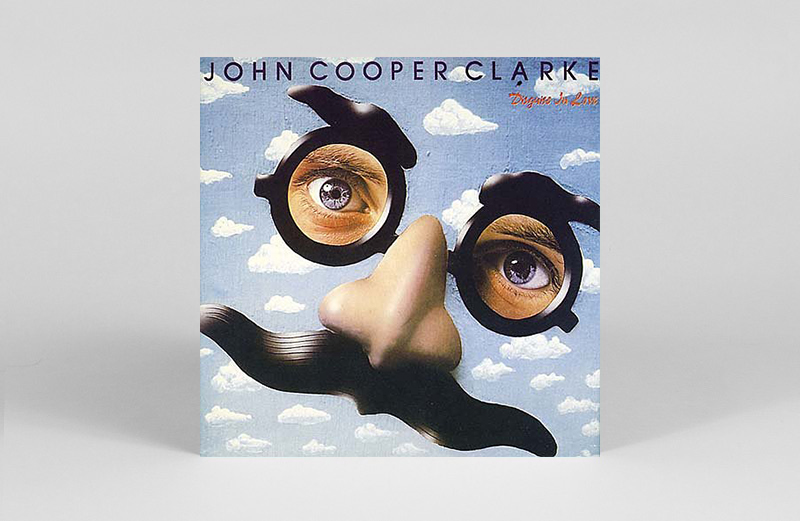

John Cooper Clarke

Disguise In Love

(CBS, 1978)

Hannett co-founded Rabid Records and produced Slaughter And The Dogs and Jilted John records with the same ‘natural’ dynamics as Spiral Scratch. But poet John Cooper Clarke’s Disguise In Love album – released on major label CBS, so there was a decent budget involved – allowed Hannett to open the portals, while getting free rein to co-write the music and play bass as one third of Clarke’s backing band The Invisible Girls (alongside drummer Paul Burgess and keyboardist Steve Hopkins). Together, they forged a bassy, dubby kind of wayward style of psychedelic lounge music to back Clarke’s scattershot poetry and flat Manc monotone. “The snare drum is the essence of rock and roll,” Hannett claimed.

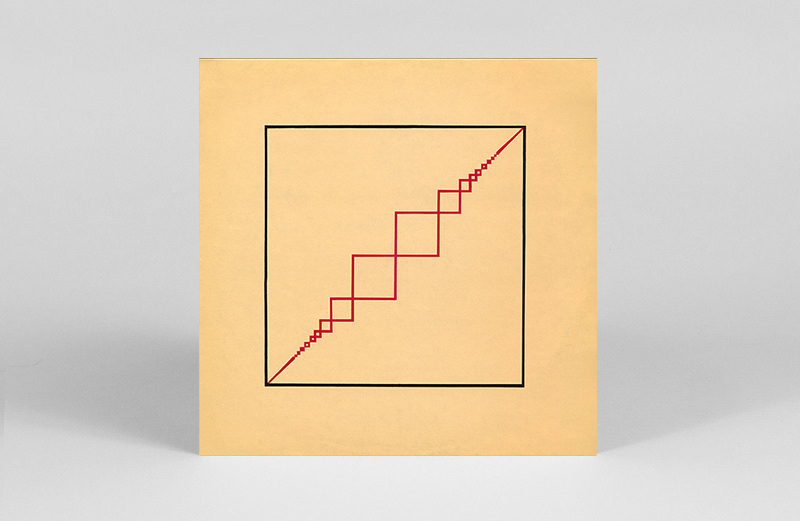

Joy Division

Unknown Pleasures

(Factory, 1979)

Hannett first advised Tony Wilson how to start a record label and then joined him at Factory Records. “He was brilliant; I could just see it in his eyes,” Wilson recalled. He always maintained Hannett was the catalyst for the way modern music now sounds, starting with drums. Hannett got hold of the first ever digital delay machine (where a machine repeats notes, like an echo) from AMS and founder Phil Nevis revealed how Hannett would describe to him the sounds he was imagining in his head, and then Nevis would modify the machine accordingly. Soon enough, the AMS was a must-have for every studio.

First, Hannett produced local synth-pop duo Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark’s debut single ‘Electricity’; his sense of space and sound created, according to OMD’s Paul Humphries, by “two FX units, a crappy little Marshall time modulator, which he put on everything, and this rack of digital delays,”. Oh, and copious amounts of marijuana – “good for the ears,” Hannett reckoned. And yet OMD decided to re-record the track without Hannett, which was the version Factory released. But as Humphries admitted, “We could never better his mix of ‘Electricity’”.

Hannett’s unique sensibility is the reason why his first album production for Factory sounds the way it does. In fact, Joy Division’s debut album didn’t even sound like the band, who complained they didn’t recognise themselves in the finished record. But as one reviewer noted, Joy Division entered the studio, “as a talented punk bund, they left it as purveyors of unique, futuristic pop music.”

The band’s mix of gothic grind and contrasting levity was future-proofed by Hannett’s bass-heavy, spacious urban sound: influenced, he told me, by dub reggae star Joe Gibbs, ‘50s country superstar Patsy Cline (“that echo, those low notes, the drums”) and The Doors’ second album Strange Days. On top, he added, “a certain disorder in the treble range,” and a distinctive drum sound via tape compression, plus “attention-grabbing things,” such as the grinding ambience of a lift – Hannett loved “found sound” and “sound effects,” said CP Lee.

“In a perverse way,” said Hannett, “I have ordered myself to re-evaluate sounds to create a different perspective, to draw attention, to shock.” This, in all its glory, was the Manchester sound.

The Durutti Column

The Return Of The Durutti Column

(Factory, 1980)

By the time guitarist Vini Reilly began recording, he was the only surviving member of The Durutti Column, as his bandmates left after Tony Wilson insisted Hannett produce them. Reilly, chronically depressed and suffering from anorexia nervosa had met Hannett at Music Force, noting “Martin seemed very untogether but he has this remarkable spark. And he was obsessed with sound. He just had this tunnel vision about creating music.”

The session began with Hannett’s “big Moog, and these funny old boxes with loads of holes, everything held together by wire and Sellotape,” said Reilly. “He didn’t engage in conversation, so I just sat in the corner while he fiddled for what seemed like hours, making funny noises. Eventually I screamed, ‘I’m fucking sick of this!’ I realised it was Martin’s method of pulling my brain around, to get me to a place that was otherworldly. Suddenly, he got this twittering bird noise, which I started playing along to, and Martin invented a very simple drum and snare pattern, and we recorded it, added a second guitar, and that’s ‘Sketch for Summer’ on the album.”

The finished Return Of The Durutti Column, “flabbergasted” Reilly, “because it sounded nothing like how I’d played the guitar. I absolutely hated it for two years, like it had nothing to do with me, but after I heard his work with Joy Division, I realised he’d given my body of work a very strong identity that I couldn’t have.”

Magazine

The Correct Use Of Soap

(Virgin, 1980)

After producing U2’s second single ‘11 O’Clock Tick Tock’, Hannett was reportedly too preoccupied by Ian Curtis’ suicide to make the band’s debut album. “He didn’t want to get into anything new,” reckoned The Edge. Yet the single’s swampy dynamics wasn’t his finest work, so it’s more likely the band vetoed Hannett, who in any case, produced several other records that year – including Pauline Murray and the Invisible Girls, an exercise in gleaming, angular pop, and Magazine’s third album The Correct Use Of Soap, “professionally, my best”, Hannett claimed.

Magazine, fronted by ex-Buzzcocks singer Howard Devoto, had crafted two multi-layered neo-prog (in other words, they’d zoomed right past ‘new wave’) albums, and Hannett was their way of dialling things back: despite the keyboards and general ambition, The Correct Use Of Soap was more Spiral Scratch than prog. The bright clarity of the Pauline Murray and Magazine albums were the polar opposite of Unknown Pleasures, showing Hannett wasn’t trapped in his crazy lab-coated persona, but could dovetail his own demands with those of the artist.

A Certain Ratio

To Each…

(Factory, 1981)

Then again, Hannett loved nothing more than to create something uniquely his, with a hermetically sealed ambience that became his trademark. If Tony Visconti told David Bowie and Brian Eno that the Eventide Harmonizer “fucks with the fabric of time,” then Hannett fucked with the fabric of space.”

“Martin had this theory about creating a room where he could hear the music in, and then tried to get that across,” explains Pete Shelley. “To me, he was an alchemist, or a mystic.” At the same time, he loved records “with that party feeling to them, like Bowie records,” and the funk-soul axis of Manchester crew A Certain Ratio was the perfect place to combine the two aspects.

After producing the studio ‘Graveyard’ half of their debut album (originally released on cassette only), Hannett really got into the swing with ACR’s vinyl album debut. To Each… was recorded four months after Unknown Pleasures, and benefits from that album’s advances; this is dank, eerie, even claustrophobic, dance music, slathered in dub echo, like it was recorded in a basement under a swimming pool.

Some criticised the band – and Hannett too – of wanting to inherit the gloomy mantle of Joy Division after the recording of Joy Division’s second album Closer and singer Ian Curtis’ suicide in May 1980. But whatever its provenance, the record still stands up as an uncannily forceful rhythmic dynamo, and in some aspects, delved deeper into an aural representation of North Manchester’s bleak industrial landscape: “a science fiction city, chemical plants, warehouses, canals, railways, and roads that don’t take any notice of the areas they traverse,” Hannett noted.

New Order

Everything’s Gone Green

(Factory Benelux, 1982)

To the devastated, insecure members of Joy Division who formed New Order after Curtis’ death, Hannett was ‘better the devil you know’, and their single ‘Ceremony’ sounded fantastic. But Hannett’s increasing use of heroin, and the experience of making New Order’s debut album Movement, soured the relationship: everyone was in mourning, and the dynamic palate is almost suffocated by a depressive fog (albeit a very beautiful depressive fog, and I think the album is still insanely underrated).

Hannett blamed guitarist/elected singer Bernard Sumner – “we couldn’t get anything out of Bernard until he was just about ready to pass out” – but Hannett also admitted he,” took more time to refine those little sonic tricks I’d invented for Closer.”

But who was responsible for the sonic trickery of New Order’s next record, the single ‘Everything’s Gone Green’? Despite the bad feelings, band and producer reunited one more time, after New Order had visited New York, and imbibed disco and electro, while drummer Stephen Morris taught himself drum programming.

The resulting single was suffused instead by sleek synths and sequencers, as if Giorgio Moroder had suddenly taken charge and injected shards of light into their signature Mancunian murk. “’Blue Monday’, which was the first thing New Order did without Martin, gets the credit as the track that changed modern music, but there’s no doubt that Bernard got it from watching Martin,” claimed Tony Wilson. “To me, ‘Everything’s Gone Green’ is the beginning of modern music, linking those early Apple computers with keyboards, which was revolutionary.”

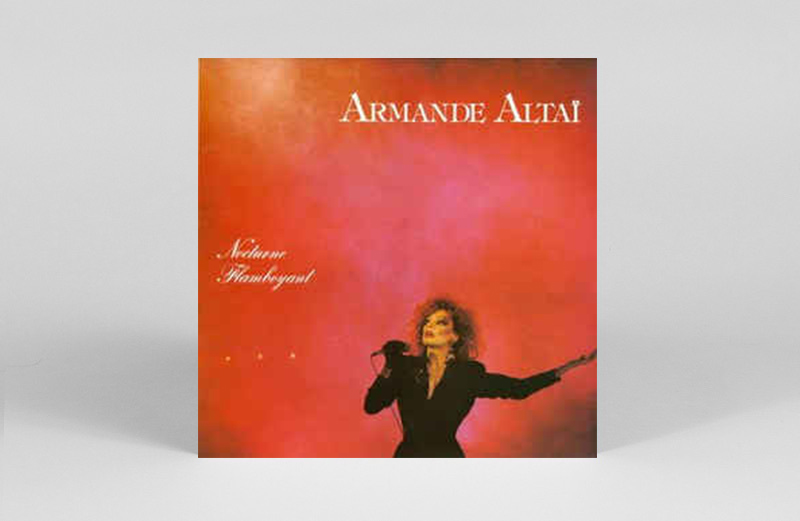

Armande Altaï

Nocturne Flamboyant

(Mercury, 1983)

Hannett also heard the future in the new sampler, the Fairlight: early adopters included Peter Gabriel and producer Trevor Horn. But demands that Factory buy him the sampler fell on deaf ears. “We said, ‘What? Sorry, we’re spending the money on a nightclub,” recalled Tony Wilson – namely, the Hacienda. “Trevor Horn gets the Fairlight and does Frankie Goes To Hollywood, and the rest is history. If we hadn’t been so mean and stupid, Martin would have invented the next stage in music.”

Given his love of found sound, the Fairlight might have consumed Hannett, figuratively and literally. As it was, he fell into a comparative slump, often producing bands – Minny Pops, The Names, The Stockholm Monsters – that had pronounced Joy Division tendencies – all good records but no challenge.

One unexpected, outlandish and forgotten commission was for the sublimely camp French-Turkish singer/actress Armande Altaï, a cross between Grace Jones, Diamanda Galas, Klaus Nomi and Amanda Lear, with a soaring operative delivery. Hannett rose to task with vertiginous synths and voluminous drums, a vaulting baroque classical/electronic hybrid that mirrored and matched the album’s title, Nocturne Flamboyant. It’s quite unlike other Hannett productions, and since its online presence is restricted to a couple of You Tube clips, one of the rarest.

Happy Mondays

Bummed

(Factory, 1988)

Wounded by his fellow Factory directors’ decision to fund the Hacienda instead of his studio arsenal, Hannett responded by suing the label. He was furious at what he perceived as being totally ripped off. “[Tony’s] made the company worth nothing, and gave me 23 percent of it”, he ranted in 1989. “Martin always took things very personally,” said CP Lee. “He considered [Factory] destroyed his whole dream. He practically lived in the studio.”

Tony Wilson also cites the impact both A Certain Ratio and New Order producing themselves, and that, “out of everyone, Ian Curtis’ death hit Martin hardest.” The lawsuit was settled out of court. Hannett received £40,000, which he sunk into heroin, while abandoning the studio: “I went back to my eight-track in my bedroom for a year,” he said.

Eventually, Hannett attempted to climb out of his hole. In 1985, he produced the first version of ‘I Want To Be Adored’ by a unproven Manchester band, The Stone Roses. Two songs, ‘So Young’ and ‘Tell Me’, were eventually released on Hannett’s own independent label, Thin Line – a sorry, sad drug reference. When it seemed unsalvageable for Hannett, Factory threw out a lifeline by suggesting he produce their new star band Happy Mondays’ second album, Bummed.

Drugs united band and producer: “He likes working with us ’cause we give him a lot of E during the sessions,” said Shaun Ryder. Taking the place of heroin, ecstasy enabled Hannett to reignite his studio nous, giving the Mondays’ endearingly shambolic shabbiness both soupy depth and sharp edges – a sound as fresh and alive as Buzzcocks’ Spiral Scratch 11 years earlier.

New Fast Automatic Daffodils

Get Better

(Play It Again Sam Records, 1990)

Hannett managed to wean himself off heroin, but like many junkies, started drinking to compensate. “By the end of my tussle with Factory I had a bottle of Jack Daniels and a seven-can-a-day habit,” he said. He worked on odd tracks with emerging bands seeking his legendary touch, such as The High and Kitchens of Distinction (who recall Hannett drinking and smoking joints until he fell asleep on the mixing desk, and still ranting about Factory). But the best of this motley bunch of recordings was a single by Manchester’s New Fast Automatic Daffodils, probably because Hannett had the experience of working with Happy Mondays, and could respond to ‘Get Better’’s frenetic, churning energy and lend the band something of his A Certain Ratio productions.

For all the strengths of ‘Get Better’, Hannett could no longer be as out-of-the-box inventive: his health, and mindset, didn’t have that kind of resilience and focus. But he’s a legend for a reason, and few producers have a book dedicated to their studio equipment and doodles.