Published on

March 16, 2017

Category

Features

Lydia Lunch, Swans’ Michael Gira and producer Martin Bisi help tell the story.

In an exclusive excerpt from We Sing A New Language: The Oral Discography Of Thurston Moore, members of the post-No Wave New York City scene tell the tale of Moore’s first experiences in a band, The Coachmen, who would ultimately be immortalised on the posthumous 1988 release Failure To Thrive.

Lydia Lunch: There are many artistic cycles either when a place is completely bankrupt or decrepit, or when a war has just happened or is about to happen. We could talk about Paris in the twenties, Germany in the early thirties, Chicago in the forties, Memphis in the fifties, Haight-Ashbury in the sixties, LA, New York and London in the late seventies, Berlin for a while in the eighties.

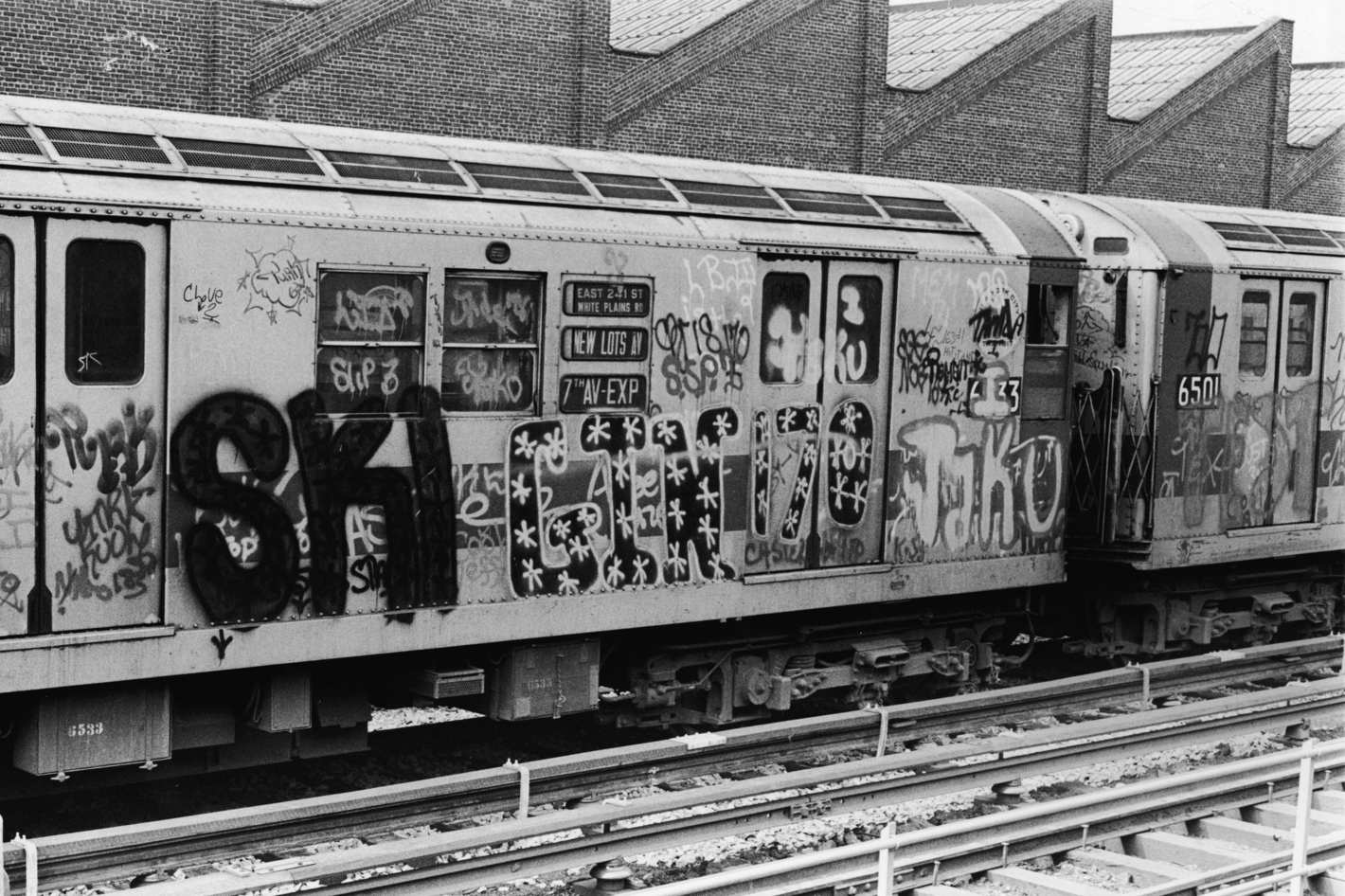

Michael Gira: Watch the movie Taxi Driver and you might get a sense of what New York was like then. The city was in a state of decline, which meant cheap rents and culturally it was quite vital — there was a lot of great art being made and music was closely associated with that. It was very difficult to survive, but the cheap rent was a plus and there were opportunities if you were headstrong and had, first and foremost, some talent.

David Keay: The subway cars, and walls everywhere, were covered in graffiti. Salsa blasted from cars, bodegas and tenement windows. Mentally ill people accosted you with zany observations and requests for money. You might get a light bulb thrown at you, or garbage dumped on you, or just get called an asshole when you passed someone on the street because they didn’t like your hair, or your jacket, or the way you walked. Nobody went west of Ninth Avenue or east of Avenue A.

J.D. King: Thurston was just a kid living in Bethel with no one to play with. He was bored, I remember him telling me that all anybody wanted to play there was Doobie Brothers songs. We were an outlet for him. He probably would have liked something more straight-ahead punk but it was still a band and we got to play out. Thurston would come down on weekends. I was 26, he was 19. At the beginning it was all these college guys, so it was cool having an official teenager. When Thurston got his apartment, late ’78 or so, East 13th Street between A and B, I visited him and remember thinking it was a scary block.

David Keay: The Coachmen were tall, shy, awkward-looking guys exuding sincerity and vulnerability. At the end of the night, I introduced myself while they were packing up. John told me that their drummer, Danny (Walworth), was leaving and we exchanged phone numbers. No more than a week later, J.D. called and I was a Coachman!

Gigs at clubs like CBGB and Max’s Kansas City often had us randomly billed with some very uncomplementary bands with far more of an affinity with Kiss than The Clash, let alone DNA. There was no particular camaraderie among unknown, struggling bands, and once a band finished its set they immediately packed up and split.

Jack Rabid: Even all those CBGB bands, in their early days, were living out of each other’s pockets. No one thought it was an odd bill when Talking Heads opened for The Ramones a half-dozen times, but a couple years later their crowds hated each other. People compartmentalise everything, it was much more healthy when people felt anything new and original could fit together in the underground.

J.D. King: We played Max’s Kansas City once. We played Tier Three once. We had some bookings at CBGB but it was a real chore — you’d have to call, get a busy signal, call, get a busy signal, over and over. Then you’d get through to this guy Charlie: “Hi, I’m from The Coachmen, we’d like a booking…” “Call next week.” Click. When we played there we often got booked with bands we had nothing in common with.

The best gigs we had were at an art space called A’s in the Lower East Side. It was an art crowd, people drank and danced. We’d gotten better, more experimental, noisier, a good rhythm section — we’d get a loft full of people dancing. We played there New Year’s Eve ’79–’80; we were playing as New Year struck. That was the happiest time. Once, at Jenny Holzer’s loft, we played with Glenn Branca’s band, The Static, the first time Glenn heard Thurston play. Also there was a place called The Botany Talkhouse — I don’t know what it was by day, it was in the floral district, it was a rock club at weekends. We played there a couple of times with Flux, Lee Ranaldo’s band, the first time Thurston and Lee met.

There were no stage antics with The Coachmen: Thurston just strumming away, none of us jumping around like Peter Townshend. We just wore whatever we wore — no rock’n’roll outfits, just presentable… I remember trying to get Thurston to sing, handing him the microphone, but he’d just move his mouth and not make any sound. I remember the first time he came to New York to visit us, he had something he’d written called ‘Monkeys From Hell’, a little punk-rock song we never played or recorded. But I could tell he had a natural ability, when we were working on material — if I came up with a chord pattern he’d come up with a complementary lead. He had a good, supple wrist for strumming.

David Keay: J.D. was the main songwriter, so ‘Thurston’s Song’ (Moore’s first recorded composition, eventually released on Failure To Thrive) was just that, an exception. It was a breezy, joyful, soulful tune that — maybe with a horn section — could have been a smash for Otis Redding or Archie Bell & The Drells. “Thurston’s getting cocky,” remarked Bob one day, with a smile. I doubt Thurston was in standard tuning for any of the songs but the sonic aggression to come would have been completely alien.

J.D. King: Failure To Thrive was recorded at a little studio in midtown, a low-end professional studio on two-track. The guys doing the recording were just ‘guys’, they had long hair and beards — tech guys, not punks. It was our demo tape and it would never have been released if Thurston hadn’t gone on to fame and fortune. To put out a seven-inch took a certain amount of money and we just didn’t have it.

Martin Bisi: There wasn’t a big recorded canon of alternative music — everything before my era, the seventies, all of that was big-budget, big-production stuff. There wasn’t a lot of multi-track, 16-24-track recording of what you’d call ‘alternative’, that wasn’t major-label funded. Literally, when I started in 1981 multi-track recording had been around six years and was hugely expensive. Even at that time, bands still tended not to go into the studio unless a label was present. People had been doing recordings with two microphones on a cassette but there wasn’t much DIY until this era. The big revolution was easy multi-tracking, where you’d be able to throw stuff down as you felt it. The equipment just started to turn over in 1980–1982. And there was no canon of what to refer to sonically, or even musically; not a sense of how these bands should sound and what should happen in a recording studio. There was no culture of recording this kind of stuff. Also, there weren’t really any avenues for doing much with the recording unless there was a label. So without a label, bands just didn’t go into studios — there was no reason to.

Byron Coley: People’s ears were tuned to something that was much more polished. So I had a lot of live tapes, I’d play them for people and they’d say, “It sounds great, but it’s just not good enough to be on record.” People thought that, to be on record things had to be professionally recorded, otherwise it was a bootleg regardless of how it was marketed. It required a sea change for people to appreciate that. Eventually, people came to like records that didn’t sound quite so pro, people got used to it, they felt like they’d cracked the code and the secret messages had become clear to them.

J.D. King: The first time we played out was winter ’78; the last time was August 1980 at an art gallery called White Columns. At that point my life was starting to change — I had a new girlfriend and I was moving out of the loft. The band just wasn’t going anywhere. I was putting a lot of work into it: finding the bookings, finding the car to get the gear to the show; since I lived at the loft it was up to me to move all the equipment back upstairs.

David Keay: With the likes of the New Romantics and neo-ska bands dominating the press’s attention, the lack of kudos or offers, and a new breed of indie rockers on the horizon — like The Minutemen or The Meatmen, whom only Thurston would have related to or concerned himself with — we all understood when John decided to fold The Coachmen.

J.D. King: That last gig though, Thurston had just been starting a new band that included him, Kim Gordon and Ann DeMarinis…

We Sing A New Language: The Oral Discography Of Thurston Moore is published by Omnibus Press. Click here to order your copy.