An introduction to the iconic British reggae label.

Founded in July 1968 as a partnership between Jamaican expatriates Lee Gopthal and Chris Blackwell, Trojan swiftly became the most important label releasing Jamaican music in Britain, as well as reggae produced by London-based Caribbean immigrants and arguably did more than any other label to elevate and disseminate reggae music.

To mark the anniversary, reggae historian and writer David Katz selects 50 of the label’s most essential releases, spanning singles and albums and chosen from original records that were issued on Trojan itself, rather than subsidiary labels.

The Wailers

‘Stir It Up’

(TR 617, 1968)

As the most famous group in the history of reggae, Bob Marley and The Wailers need no introduction here, but it is worth noting that they had already been recording for about five years before this self-produced single reached the Trojan label in 1968. Texan crooner Johnny Nash had much better success with his later cover version, yet this spirited original holds much more bite, with its relaxed harmonies and Marley’s playful lead offset by an eerie piano line, minimal guitar and percussion.

The Uniques

‘Watch This Sound’

(TR 619, 1968)

An influential record with an uncanny, disjointed rhythm and harmonic brilliance, ‘Watch This Sound’ is a reggae adaptation of Buffalo Springfield’s anti-Vietnam War protest anthem, ‘For What It’s Worth’, the title and choral refrain reportedly altered because backing vocalist Jimmy Riley misheard the lyrics of the original. One of the earliest recordings to feature the bass playing of Aston “Family Man” Barrett – who would go on to make waves internationally in The Wailers band – ‘Watch This Sound’ was arranged by keyboardist and vocalist Lloyd Charmers and financed by Winston Lowe, a lesser-known producer of Chinese descent whose Tramp label was based in the Greenwich Farm ghetto of western Kingston. Other featured musicians include drummer Winston Grennan, keyboardist Ansel Collins and leading rock steady guitarist, Bobby Aitken.

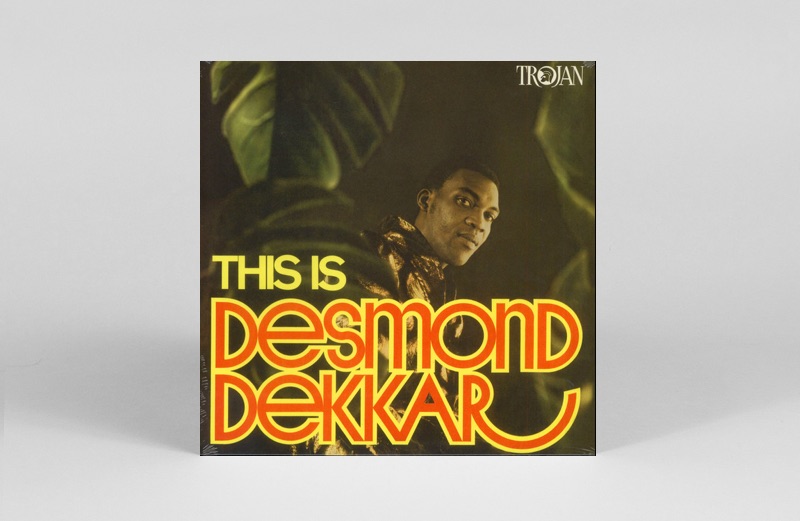

Desmond Dekker

This Is Desmond Dekkar

(TTL 4, 1969)

After a chaotic childhood that saw him partially enrolled at the Alpha Boys School before being farmed out to extended family members in the countryside, Desmond Dacres became Desmond Dekker under the wing of Leslie Kong at Beverley’s in the ska years, though he really came into his own in rock steady. Debut LP This Is Desmond Dekkar gathers the best of his mid-1960s work, finding his falsetto largely in cool and relaxed mode, even when singing of the hardships of the ghetto on ‘007’, or the allure of street-gang life on ‘Rudy Got Soul’.

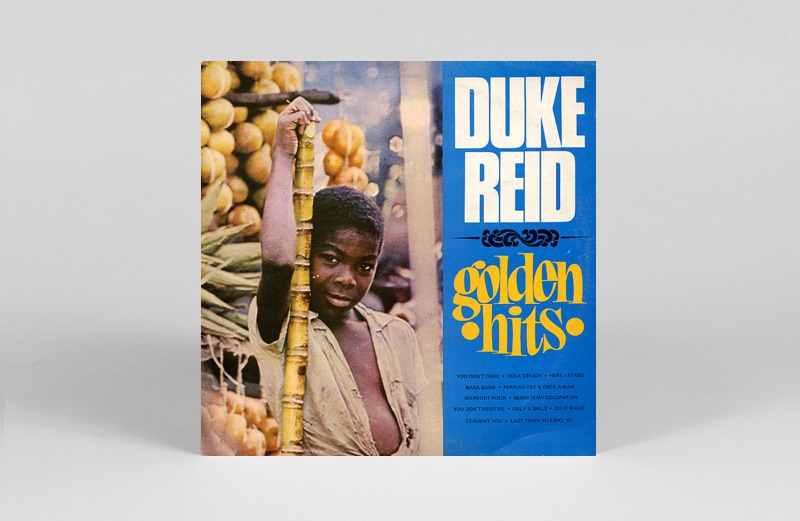

Various Artists

Duke Reid’s Golden Hits

(TTL 8, 1969)

The quintessential rock steady producer, former policeman Arthur Reid became “Duke Reid the Trojan” by commanding Jamaica’s largest and most powerful sound system in the 1950s, transported by his Trojan flatbed truck. In ska he was somewhat in the shadow of Clement “Sir Coxsone” Dodd of Studio One, but ruled the roost in rock steady with the landmark hits gathered here, such as The Techniques’ ‘You Don’t Care’, Justin Hinds and The Dominoes’ ‘Here I Stand’, The Jamaicans’ ‘Baba Boom’ and Alton Ellis and The Flames’ genre-defining ‘Rock Steady’.

John Holt

‘Ali Baba’

(TR 661, 1969)

John Holt’s earliest recordings were made in the ska years, cutting duets with Alton Ellis for Randy’s and a sole 45 for Leslie Kong. Once he was drafted into The Paragons, his vocal strength and dominant personality made him leader of the group, forcing Bob Andy to go solo. Under Holt’s command, The Paragons became one of the most popular acts of the rock steady era. By 1968 he was scoring hits as a solo artist too, mostly for Duke Reid, who had been The Paragons’ chief producer. The hallucinatory ‘Ali Baba’ is a particularly unusual disc, describing a range of nursery rhyme and folktale characters that were special guests in Holt’s vision. The perennial favourite would be reworked by other producers in future years.

Harry J All Stars

‘The Liquidator’

(TR 675, 1969)

The distinctive organ melody of ‘The Liquidator’ has a way of getting under your skin, so much so that it became a chart success in Britain, despite a lack of radio airplay. The song had a complicated genesis, beginning as the vocal ballad ‘What Am I To Do’, voiced by aspiring singer Noel Bailey (later known as Sowell Radics), for upcoming producer Tony Scott, who enlisted the help of Harry ‘J’ Johnson for distribution. In Johnson’s care, the rhythm was revisited by keyboardist Winston Wright, who totally transformed the track with his melodic organ caresses. The song became a favourite on British football terraces and is still heard today.

The Melodians

‘Sweet Sensation’

(TR 695, 1969)

The Melodians had some advantages over their competitors in that two of their three vocalists sang lead, so that Brent Dowe’s deeper tenor was sometimes supplanted by the higher, tremulous voice of founding member Tony Brevett, who was nephew of Skatalites bassist Lloyd. Along with fellow harmony specialist Trevor McNaughton, they also had a silent writing partner, Renford Cogle. After flitting between Studio One, Treasure Isle and Sonia Pottinger’s High Note, at the end of the 1960s they began working for Leslie Kong, scoring more exceptional hits in the emerging reggae style. Love song “Sweet Sensation” was massively popular, with Dowe’s shining lead backed by spectacular harmony from the rest.

Various Artists

Tighten Up Volume 2

(TTL 7, 1969)

Trojan’s cut-price LP series, Tighten Up, was a keen gem of record retail. Since much of their young audience could not afford to purchase several singles on a regular basis, Tighten Up made the new reggae sound accessible by gathering the latest hits on a budget long player, bringing the music into the homes of many white working-class youth, as well as Caribbean expats. Mixing chart hits like The Pioneers’ racetrack saga ‘Longshot Kick The Bucket’ and The Upsetters’ New Orleans sax groove ‘Return Of Django’ with Rudy Mills’ forlorn ‘John Jones’, Dandy’s playful ‘Reggae In Your Jeggae’ and The Kingstonians’ protest record ‘Sufferer’, Tighten Up Volume 2 became a skinhead soundtrack for the white working-class British subculture that took its musical cues and dress sense from the “rude boys” of Jamaica.

The Sensations

‘Every Day Is Just A Holiday’

(TR 7701, 1969)

West Kingston harmony group The Sensations were formed in the mid-1960s by Jimmy Riley and Stanley “Buster” Riley (the latter not related to Jimmy, but the brother of producer Winston Riley), along with Bobby Davis and Cornell Campbell. The shifting line-up meant members drifted in and out, with Jackie Parris replacing Jimmy pretty early. By 1970, Parris and Buster joined with guitarist Radcliffe “Dougie” Bryan to back Johnny Osbourne’s material for Winston Riley. The celebratory ballad ‘Every Day Is Just A Holiday’ was a massive Jamaican chart hit in 1969 that would prove never to fall out of fashion, having been licked over many a time since.

Jimmy Cliff

‘Vietnam’

(TR 7722, 1969)

Jimmy Cliff’s hard hitting anti-war opus described a soldier’s tragic death on the battlefield, shortly before the end of his conscription in Vietnam. Marked out by rim-shot drumbeats, the song was made more foreign-friendly with soulful female choruses and a baritone sax, and made a strong impact on the rock and folk aristocracy on both sides of the Atlantic. Bob Dylan reportedly rated it the best of all protest songs on the conflict, leading Paul Simon to travel to Jamaica to record “Mother And Child Reunion” with the same backing band at Dynamic Sounds studio.

The Maytals

‘Sweet And Dandy’

(TR 7726, 1970)

Toots and The Maytals conquered Jamaica’s hearts and minds with a blend of gospel and soul, wrapped up in the emerging reggae idiom. ‘Sweet And Dandy’, one of several recordings they made that won the island’s annual Festival song competition, had widespread appeal in its finely-balanced choral harmonies, delivered in a countryside vernacular atop an off-kilter rhythm that held echoes of the cadences of rural Jamaica, which ultimately have African underpinnings. Listen closely and you will find an eyewitness account of the wedding of a certain Ettie and Johnson, and the “sweet and dandy” fete that results from their union, despite the avaricious greed of their guests who dress up in white, Toots suggests, merely to get a slice of the wedding cake.

Ken Boothe

‘Freedom Street’

(TR 7756, 1970)

Ken Boothe got his start in a duo with Stranger Cole, cutting hits like ‘Uno Dos Tres’ for Duke Reid and ‘World’s Fair’ for Coxsone Dodd, who convinced Boothe to go solo. Though he remained largely at Studio One to the end of the ’60s, he also scored hits for Sonia Pottinger, Phil Pratt and others, yet some of his finest work was recorded for Leslie Kong in the early 1970s, with the rousing ‘Freedom Street’ an outstanding example of Boothe’s social commentary, the release from mental slavery co-penned by Gaylads founder, BB Seaton.

Carl Dawkins

‘Satisfaction’

(TR 7765, 1970)

Carl Dawkins is an emotive reggae singer whose expressive delivery drew on the soul of Otis Redding. Hanging out in the record shop run by Carl ‘Sir JJ’ Johnson on Orange Street, Dawkins convinced the producer to take a gamble on his talent, scoring instant hits with ‘Baby I Love You’ and ‘Hard Times’. The disjointed rhythm of ‘Satisfaction’ was apparently based on a human heartbeat, and it is two and half minutes of sheer musical power, knocking ‘Freedom Street’ out of pole position on the Jamaican charts.

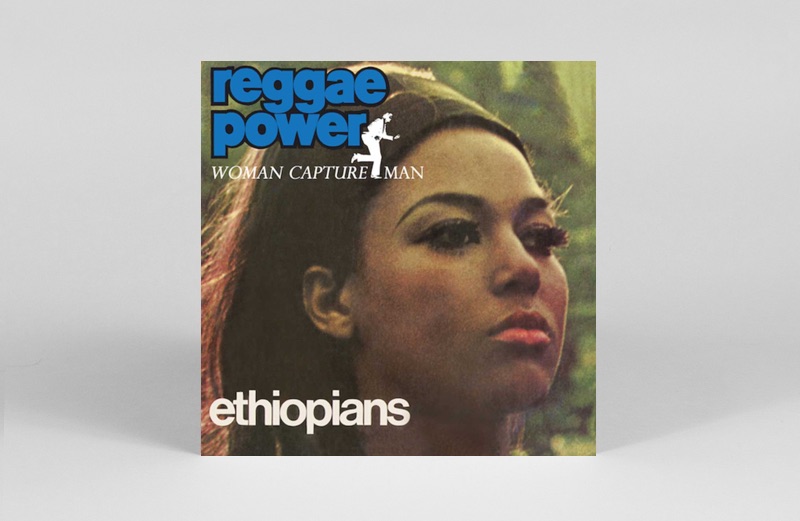

The Ethiopians

Reggae Power

(TTL 10, 1969)

After cutting some ska work as a solo artist at Studio One under the name Jack Sparrow, Leonard Dillon formed The Ethiopians with Stephen Taylor and Aston Morrison, recording for Studio One, Sonia Pottinger, Leebert Robinson and Lee Perry, settling in for a long fruitful relationship with hit-making reggae producer, Carl ‘JJ’ Johnson. Reggae Power showcased their versatility, with ‘Hong Kong Flu’, ‘Everything Crash’ and ‘Gun Man’ exploring topical issues, devotional track ‘Feel The Spirit’, and ‘Women Capture Man’ describing the allure of the miniskirt.

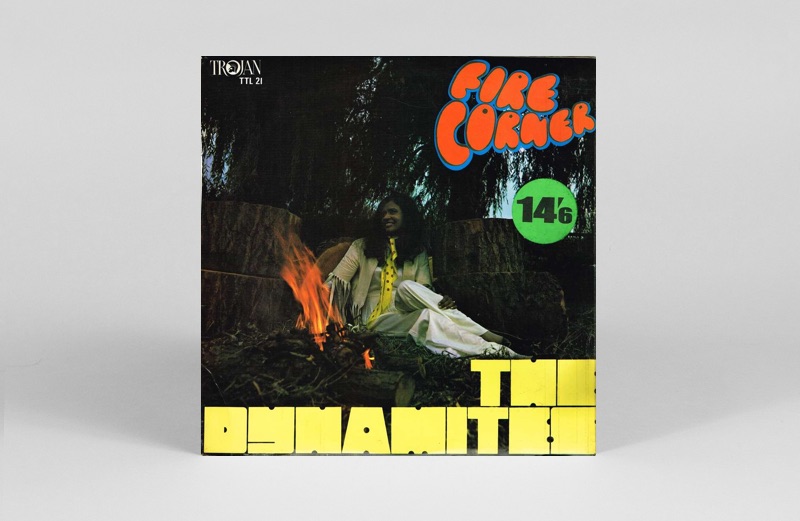

The Dynamites

Fire Corner

(TTL 21, 1969)

Producer Clancy Eccles got his start as a singer at Studio One, but soon realised his only chance of earning properly would be in switching to producing music and staging live concerts. He launched Clandisc and other labels in the tail end of rock steady and helped usher in the new reggae style, scoring some of his biggest hits via the shouted interjections of deejay King Stitt, whose ‘Fire Corner’ became the title track of his debut Trojan long-player. Most of the other tracks are organ instrumentals cut by Clancy’s house band, but Stitt really shines on the title track, as well as the tonic-saluting ‘Vigorton 2’.

Johnny Osbourne and the Sensations

Come Back Darling

(TTL 29, 1970)

Johnny Osbourne received strong musical grounding at the Alpha Boys School, developing his rich, deep tenor. He cut the stunning ‘All I Have Is Love’ at Studio One in 1969 with a group dubbed The Wild Cats, but soon shifted to fronting The Sensations, recording this strong debut album for astute producer Winston Riley. In addition to the outstanding title track, ‘He Who Keepeth His Mouth’ and ‘The Warrior’ were sizeable hits, though the few organ filler tracks point to the fact that Johnny migrated to Canada before an album’s worth of material had been committed to tape.

Jo Jo Bennett

‘Leaving Rome’

(TR 7774, 1970)

During the late ’60s and early ’70s, Trojan often resorted to orchestration to break reggae in the UK. The media climate was typically hostile to the music, with the BBC operating an almost total ban. By bringing material from Jamaica to London for string overdubs (typically overseen by Johnny Arthey), the company stood a better chance of reaching the charts. Purists often complain about the process, with Bob and Marcia’s ‘Young Gifted and Black’ a particular stickling point, but flugelhorn player Jo Jo Bennett’s ‘Leaving Rome’ proves that the result could be intriguing, and even enchanting in the right hands.

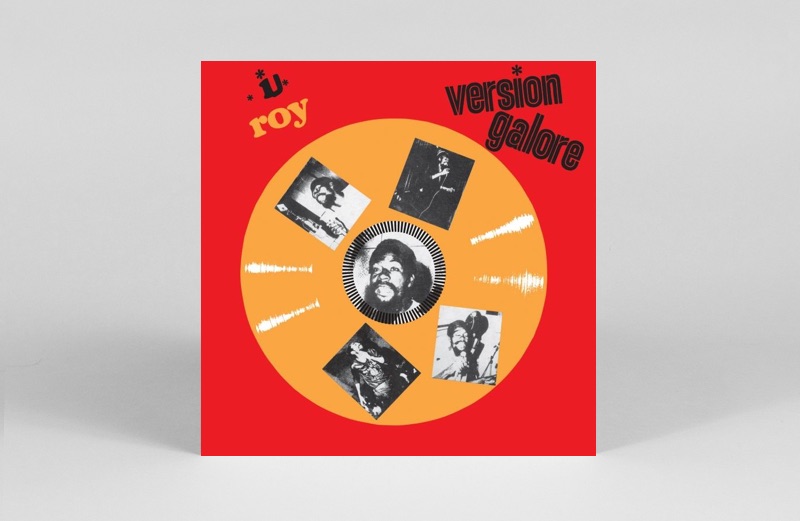

U Roy

Version Galore

(TB 161, 1971)

The recordings that U Roy made at Treasure Isle studio at the dawning of the 1970s dramatically redefined the role of the deejay, that is, the microphone fiends that would spice-up proceedings on Jamaican sound systems, first by making rhymes between records and later by “toasting” over instrumental B-sides. The revolution started by U Roy’s innovations at Treasure Isle would ultimately help spawn rap in America, and strangely, the rhythms that were used on the singles that make up this ground-breaking debut LP were not the freshest from Duke Reid’s reggae productions, but rather vintage back-catalogue rock steady from The Paragons and The Melodians. The awesome result is a timeless classic.

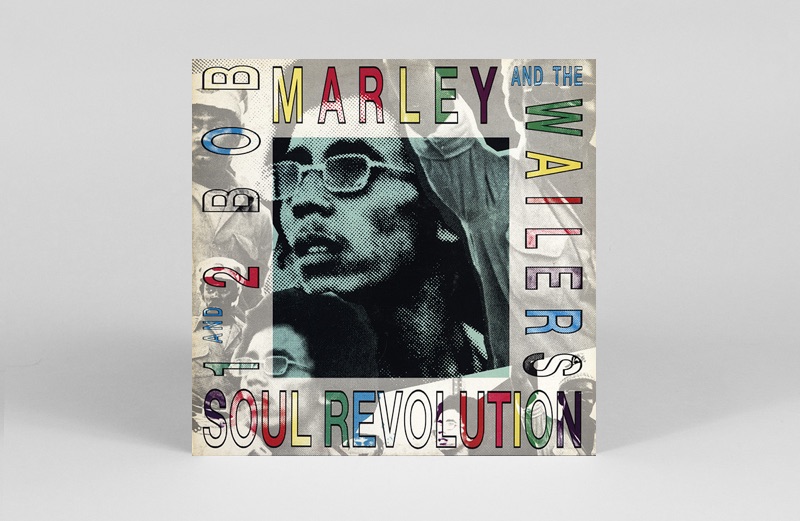

Bob Marley and The Wailers

Soul Revolution 1 and 2

(TRLD 406, 1988)

The work that Bob Marley and The Wailers recorded with Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry at the start of the 1970s is truly astounding, being some of the greatest either produced during their respective careers. Yet, when Trojan issued the Soul Rebels album in 1970, response from the British public was lukewarm, so the company initially passed on the follow-up, Soul Revolution, causing tracks from both to later surface on the African Herbman and Rasta Revolution compilations. Thankfully, Trojan staff eventually had the good sense to issue Soul Revolution with its proto-dub counterpart as a double-disc item, allowing us to hear these immortal works in an entirely new way.

The Melodians

‘Rivers Of Babylon’

(TRM 9005, 1970)

One of the last recordings to emerge from their successful tenure with Leslie Kong in the early 1970s, ‘Rivers Of Babylon’ was a true landmark for The Melodians, arriving as an unexpected Rastafari adaptation of a traditional Christian hymn. The song was a big hit in Jamaica and would reach wider audiences after its eventual inclusion on the soundtrack of The Harder They Come. Later still, the song would go on to inspire the tremendous success of the schlock-manufactured disco group, Boney M, yet it is naturally the Jamaican original that remains so uniquely appealing.

Ernie Smith

‘Pitta Patta’

(TR7859, 1972)

Smooth crooner Ernie Smith got his start at Federal in the rock steady era, but hit his stride at that stable during the early 1970s, typically with humorous songs of everyday life, though he also cut the occasional hard-hitting song of social commentary. ‘Pitta Patta’ is a witty ditty about the sound of raindrops falling on Smith’s roof as he canoodles with his lady indoors. The song was such a popular hit in Jamaica that Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry adapted it on his Cloak And Dagger instrumental album, and also chopped up the rhythm on ‘Cow Thief Skank’.

The Vulcans

‘Star Trek’

(TR 7863, 1972)

Every once in a while Trojan released an extraordinary record that pushed the boundaries of reggae and The Vulcans’ ‘Star Trek’ is very much that beast. Many reggae tunes got their finishing touches in London after having been laid in Jamaica, and at Chalk Farm studio in north London, Ken Elliott was the go-to man for Moog synthesizer overdubs. At the behest of Trojan staffers Joe Sinclair, Webster Shrowder and Desmond Bryan, here Ken blasts a heavy, Rico Rodriguez instrumental dub procured from Bunny Lee into the stratosphere, courtesy of intergalactic portamento space bleeps. The vibrant hand percussion, choppy piano from Sinclair, a bit of added guitar from Trevor Starr of the Cimarrons and Rico’s original horn line all form startling musical contrasts to the synth as the track blows us to outer space and back again.

Nicky Thomas

‘Have A Little Faith’

(TR 7885, 1973)

Many Jamaican artists need to pass a phase of apprenticeship, doing odd jobs and more for producers in the hopes of gleaning a chance to get their voice onto a record. Nicky Thomas is no exception, having swept out Joe Gibbs’ studio many a time during the early 1970s in the hope that the producer would give him a break. Early recordings for Gibbs and Derrick Harriott did not reach very far, until his reggae take on ‘Love Of The Common People’ reached the British pop charts with the help of orchestration. In contrast, ‘Have A Little Faith’ is a pure Thomas original that has remained in constant demand with reggae fans of a certain age. It is a tune you are still likely to hear at house parties, as well as on the so-called ‘revival reggae’ nightclub circuit.

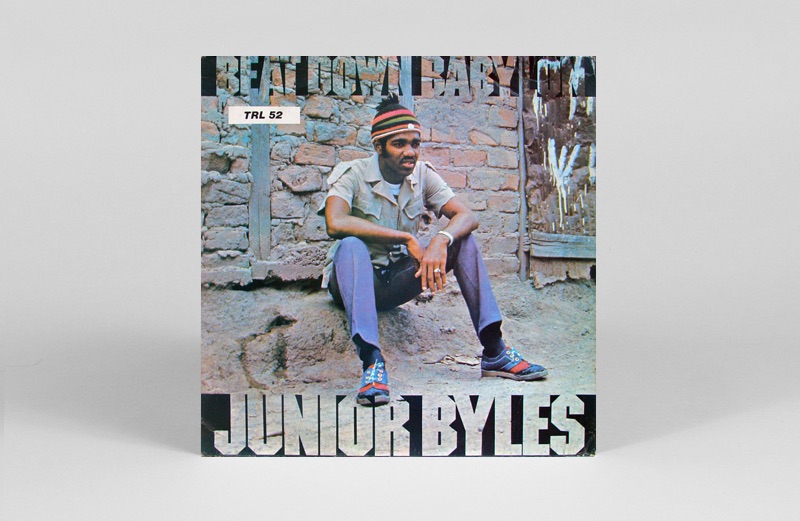

Junior Byles

Beat Down Babylon

(TRL 52, 1972)

Kerry Byles Junior started his career in The Versatiles harmony group, recording for Joe Gibbs, Dorothy Barnett and Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry during the late ’60s and early ’70s. After Bob Marley and The Wailers broke away from Perry’s stable to form their own Tuff Gong label, Perry made Byles his primary focus, yielding this excellent debut album, which mixed hard-hitting protest songs with romantic ballads. Along with the monster hit that is the title track, there’s the autobiographical ‘Poor Chubby’, the yearning ‘A Place Called Africa’, and the nonsensical Festival song winner ‘Da Da’.

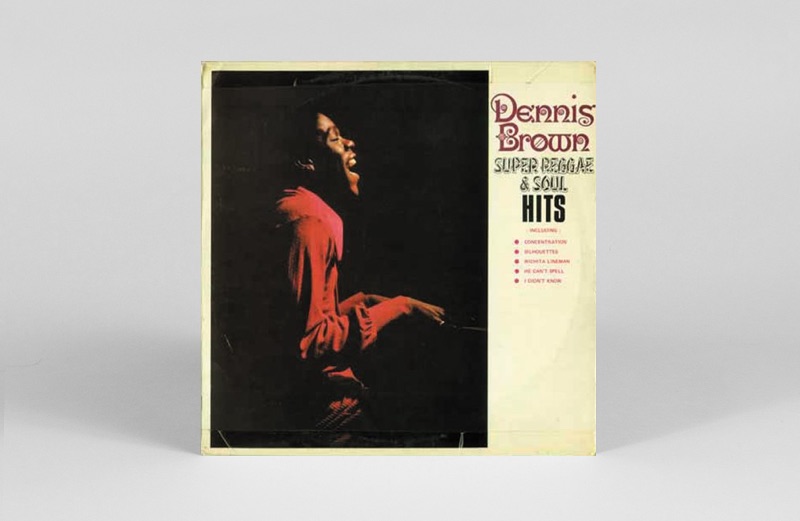

Dennis Brown

Super Reggae And Soul Hits

(TRLS 57, 1973)

Later dubbed ‘The Crown Prince of Reggae’ for essentially being in the same league as Bob Marley, Dennis Brown was an exceptional singer and songwriter who remains among Jamaica’s best-loved vocalists. Prepared for stardom by Derrick Harriott in the late 1960s, he came to prominence at Studio One, where he recorded his first two albums as well as numerous hit singles. Super Reggae And Soul Hits was then recorded for Harriott, an excellent blend of emotive originals and choice cover tunes. Outstanding tracks include the opening ‘Concentration’, which comes complete with its dub counterpart, as well as the intriguing ballad ‘Lips Of Wine’ and the topical ‘Changing Times’. Cover tunes ‘Silhouettes’ and ‘Wichita Lineman’ are also exceptional.

Big Youth

Screaming Target

(TRLS 61, 1973)

During the early 1970s, Big Youth helped revolutionise the deejay form by shifting it overtly towards Rastafari consciousness. His debut album, Screaming Target, is easily one of the best deejay albums ever recorded. It dates from 1973, when the tall, lanky toaster was at the height of his powers, the album deftly produced by Gussie Clarke and the rhythm tracks absolutely faultless. There are fine cuts of Leroy Smart’s broken-hearted ‘Pride And Ambition’, Roman Stewart’s hopeful ‘Try Me’ and Gregory Isaacs’ proverb-laden ‘One One Cocoa’, as well as the popular title track, which rides KC White’s version of the irresistible ‘No No No’ rhythm, to make garbled reference to the film Sitting Target, which Youth claims is “ranker than Dirty Harry!”

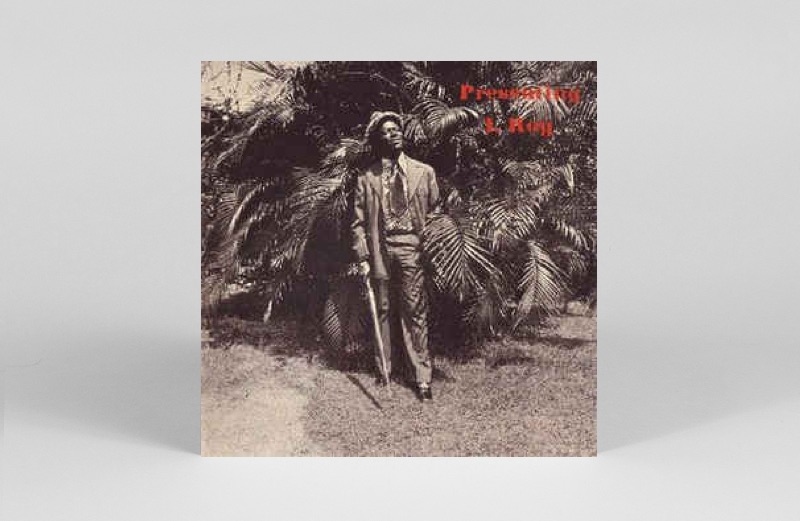

I Roy

Presenting I Roy

(TRLS 63, 1973)

As with Screaming Target, I Roy’s debut album had a lot going for it because it was produced by Gussie Clarke, so the rhythms were chosen with care by a true connoisseur of Jamaican sound system culture. ‘Blackman Time’ rides a killer cut of Lloyd Parks’ ‘Slaving’, ‘Tripe Girl’ utilises the 1972 rework of The Heptones’ misogynist treatise, and ‘Pusher Man’ transforms Alton and The Heptones’ broken-hearted ballad into a warning against urban drug lords. The toasting is dextrous throughout, and our hero always makes the rhyming sound easy, rendering the disc a pleasure from start to finish.

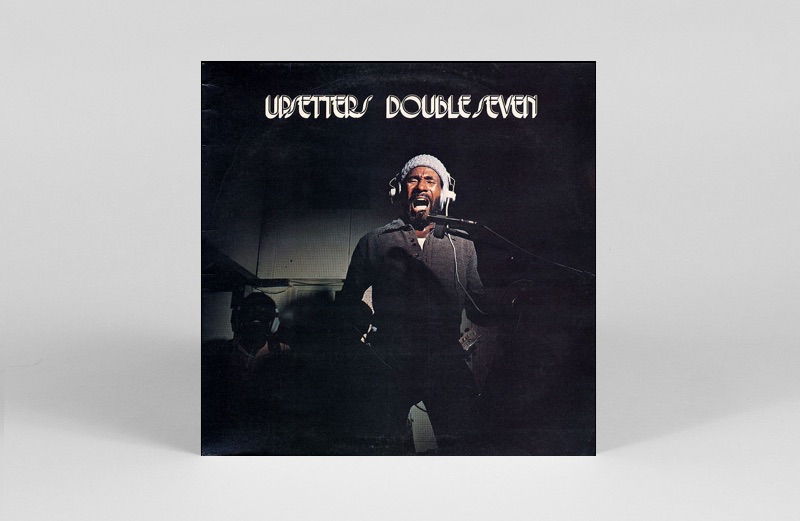

The Upsetters

Double Seven

(TRLS 70, 1973)

The mixed bag that is Double Seven was assembled by Lee Perry shortly before opening his own Black Ark studio. Most of it was laid at Dynamic Sound and much was voiced and mixed at King Tubby’s, with more icing on the aural cake in the form of Moog overdubs from Ken Elliot at Chalk Farm in London; as heard most notably on the excellent hymn to fried chicken, ‘Kentucky Skank’, as well as the oddball dub of ‘Ironside’. There are also great dub cuts to Perry’s ‘Jungle Lion’ and an augmented ‘Justice To The People’, the latter made more vocally strange by wordless Wailers choruses. With U Roy waxing lyrical about gambling on ‘Double Six’, and I Roy warbling about London’s ever-present ‘Hail Stones’, there is plenty to discover from this last long-playing gasp of creativity, prior to the opening of the Ark.

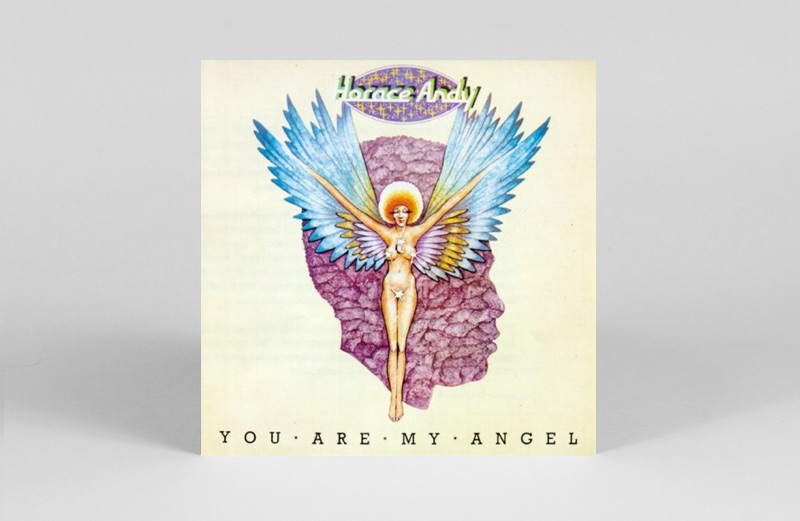

Horace Andy

You Are My Angel

(TBL 197, 1973)

At the start of the 1970s, Horace Hinds moved to Studio One, and changed his name to Horace Andy in deference to Bob Andy, the younger singer’s trembling falsetto carving a unique niche. ‘Skylarking’ was the breakthrough hit that led to his first album release in 1972, but as with many others before him, Andy found that financial recompense was not as it should be. He thus teamed up with Bunny Lee for this sophomore album, the first to be released outside of Jamaica. Along with the stunning title track, there’s a great take of Bill Withers’ ‘Ain’t No Sunshine’, and everything was voiced and mixed at King Tubby’s studio.

Toots and The Maytals

‘Louie Louie’

(TR 7865, 1972)

During the early 1970s, Toots and The Maytals enjoyed a long tenure at Byron Lee’s Dynamic Sounds stable, working closely with keyboardist Warwick Lyn, who was typically in charge of the musical arrangements, and other in-house practitioners such as keyboardist Neville Hinds. Chris Blackwell had been trying to break the group internationally for quite some time, with varying degrees of success, and though their originals were always popular at home in Jamaica, some of their cover tunes fared better overseas. This irresistible version of the endlessly-covered ‘Louie Louie’ gives us the best of both worlds in the form of a song we all know and love, yet one which has been totally Jamaicanized by Toots and the supporting musicians.

Ken Boothe

‘Is It Because I’m Black’

(TR 7893, 1973)

The emotive power of Ken Boothe’s voice made him a natural choice for soul and funk covers, especially those with strong messages to convey. Ken’s impeccable version of Syl Johnson’s ‘Is It Because I’m Black’ was expertly produced by keyboardist and vocalist Lloyd Charmers, who had a long history of adapting American tunes in reggae himself, and the combination is simply dynamite here. If anything, the bass-heavy rhythm sounds strangely understated, with an aggravating piano and ghostly lead guitar both amplifying Boothe’s disquieting vocals. The track delivers on every single level, pulling the listener in from the very first note.

Zap Pow

‘This Is Reggae Music’

(TR 7941, 1974)

The jazz-based roots reggae act Zap Pow were loaded with instrumental talent. The group spun off from The Mystics, formed by trumpeter David Madden and the visionary saxophonist Cedric ‘Im’ Brooks at Studio One, before Brooks gravitated towards Count Ossie, prompting Madden to form Zap Pow with drummer Danny Mowatt, bassist Mikey Williams and guitarist Dwight Pinkney. The peculiar ‘Mystic Mood’, adapted from a schmaltzy Francophone ballad, was their first hit, though it was totally surpassed by ‘This Is Reggae Music’, the celebratory single, co-produced by Chris Blackwell at Harry J’s studio, with the added strings arranged by Harry Robinson. Surfacing on Trojan via a licensing deal with Island, the song was issued by Blackwell in various formats on different labels, but never quite achieved the stellar status it was due.

Inner Circle

‘Forward Jah Jah Children’

(TR 7948, 1975)

Inner Circle’s convoluted history is intricately linked to that of Third World. The first incarnation of the group dates back to the late 1960s, featuring Cat Coore, Ibo Cooper, Carl Barovier and Bunny Rugs, who fronted the group to 1971 (not counting the year 1969-70, when he was temporarily replaced by Bruce Ruffin while in New York). Bassist Ian Lewis and his guitarist brother Roger then became key members of the group, and when Cat Coore left in 1973, Lloyd ‘Tin Legs’ Adams became the drummer and Philip Thompson lead vocalist. Everything changed when Jacob Miller became the charismatic front man, his gritty voice channelling a group once known for cheesy cover tunes into songs of righteous rebellion. ‘Forward Jah Jah Children’ was one of the first recordings he made with Inner Circle, and it still ranks as one of their best.

Gregory Isaacs

‘Sinner Man’

(TR 7951, 1975)

One of the few reggae icons to reign at the very forefront of the movement, Gregory Isaacs issued a range of material during his lengthy career. Most will always remember him for the love songs and dejected ballads which cast him as a vulnerable romantic, yet he also cut plenty of superb songs of social protest, as well as odes of Rastafari consciousness. Very much in this latter vein, ‘Sinner Man’ is an excellent and little-known track, squeezed away on the B-side of a gratuitous Marley cover. Produced by Sidney Crooks of The Pioneers, it shows the strength of Isaacs’ vocal delivery, spitting barbed fire against hypocritical preachers and other wrongdoers.

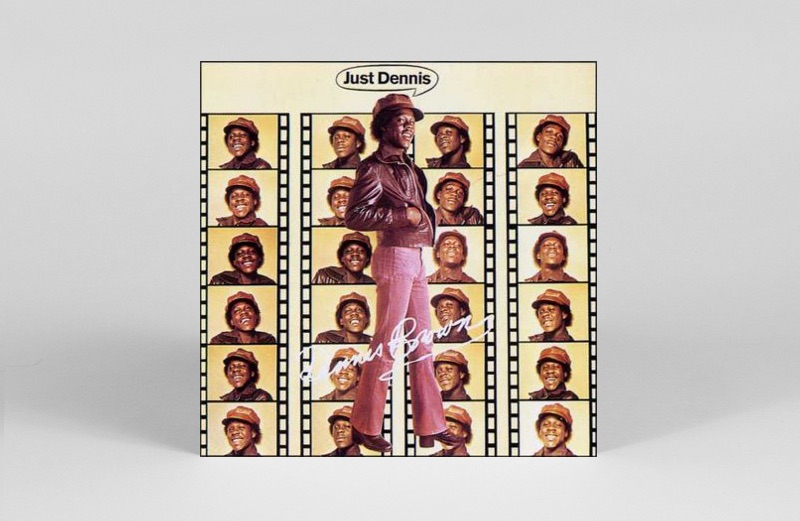

Dennis Brown

Just Dennis

(TRLS 107, 1975)

The intense creative partnership that Dennis Brown formed with producer Niney the Observer during the mid-1970s brought forth some of the greatest roots reggae ever recorded. A longstanding favourite with Jamaican audiences, Brown’s work had not yet broken through to the outside world. After pairing him with the Soul Syndicate band and voicing and mixing his work at King Tubby’s studio, Niney’s links with Trojan made major inroads overseas, preparing Brown for the eventual superstardom that would come through ‘Money In My Pocket’. The album Just Dennis showcases the cream of their vibrant partnership, being filled with anthem-like hits, such as ‘Westbound Train’, ‘Cassandra’, ‘No More Will I Roam’, ‘Conqueror’ and ‘Africa’.

Augustus Pablo

Ital Dub

(TRLS 115, 1974)

Horace Swaby became Augustus Pablo while working as a session musician for Herman Chin-Loy, though it had been an alias for Lloyd Charmers first. Swaby’s claim to fame was his transformation of the melodica – a blown plastic keyboard used to teach children the rudiments of melody – into an instrument of wonder and grace. After his early work for Chin-Loy, Swaby cut important work for Clive Chin at Randy’s and began his own productions, too. The Ital Dub album was produced by Tommy Cowan before Swaby got his Rockers label fully off the ground, and since it was mixed at King Tubby’s studio, there is plenty of ethereal echo and delay. Highlights include the moody ‘Big Rip Off’, a Jacob Miller dub, and melodica dubs of Junior Byles’ ‘Curly Locks’, Tosh’s ‘Burial’, and Marley’s ‘Three O’Clock Road Block’.

Big Youth

‘Wolf In Sheep’s Clothing’

(TR 7972, 1975)

As Big Youth’s career evolved, he continued to score hits for various producers while he concentrated on his own productions, issued on labels such as Negusa Negast and Nichola Delita. He also began broadening his vocal approach, shifting to singing on some tracks, and performing mid-way between singer and toaster on others, pioneering the emerging form known as ‘sing-jay.’ ‘Wolf In Sheep’s Clothing’ is an exceptional self-production that defies classification – a half-spoken, occasionally sung meditation on all manner of issues, voiced over the rock-hard rhythm of Desi Roots’ ‘Warning’.

Derrick Harriott

‘Eighteen With A Bullet’

(TR 7973, 1975)

Derrick Harriott is a truly versatile player in the reggae music industry. A singer-songwriter with a side-line in cover tunes, as well as an excellent music producer, he released a wide spectrum of material, ranging from cheesy cover tunes and disco experiments to hardcore roots reggae and dub. Harriott’s version of Pete Wingfield’s ‘Eighteen With A Bullet’ is pure enjoyment, his expressive voice amply backed by The Chosen Few, with that killer organ solo appearing mid-way as an added bonus.

Big Youth

‘Hit The Road Jack’

(TR 7977, 1976)

As noted above, Big Youth began broadening his music palette in the mid-1970s to incorporate more singing into his output. His relaxed take of Ray Charles’ ‘Hit The Road Jack’ does not bother to try and be too faithful to the original. Instead, Youth draws in some of Dionne Warwick’s ‘Love Sweet Love’, while the horns, drum and bass give the whole thing an unwarranted dub underpinning. As with much of Big Youth’s Reggae Phenomenon oeuvre in this shifting phase, ‘Hit The Road Jack’ is simply oozing with irresistible appeal.

John Holt

‘You’ll Never Find Another Love Like Mine’

(TR 7991, 1976)

After moving away from Duke Reid’s Treasure Isle stable, where he recorded many of his biggest hits, both as a member of The Paragons and as a solo artist, John Holt was essentially a freelance artist, working with whoever had the means to get the maximum exposure for his work. However, his working connection with Bunny Lee remained particularly strong, resulting in some of his most noteworthy material. Holt’s relaxed, confident and emotive take of Lou Rawls’ ‘You’ll Never Find Another Love Like Mine’ is another prime example of the way that talented Jamaican singers could completely refashion a song from another genre.

Linval Thompson

I Love Marijuana

(TRLS 151, 1978)

Roots reggae singer Linval Thompson spent part of his youth in New York, where he gained experience in expatriate acts Hugh Hendricks and the Buccaneers, and The Bluegrass Experience. During the early 1970s, he recorded a series of underground 45s for New York-based reggae producers, and upon returning to Jamaica in 1974, cut noteworthy material for Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry at the newly opened Black Ark, as well as Phil Pratt and other producers. Breakthrough hits for Bunny Lee led Linval to begin producing himself, first on bartered rhythm tracks. I Love Marijuana is an excellent roots album from Linval, tackling a range of subjects over the tough backing of The Revolutionaries at Channel One studio. In addition to the weed anthem title track, there is the defiant ‘Dread Are The Controller’, the romantic saga ‘Big Big Girl’ and a decent cover of Ken Boothe’s ‘Just Another Girl’.

Linval Thompson

Negrea Love Dub

(TRLS 153, 1978)

Negrea Love Dub is another intriguing set from Linval, with super dubs of tracks such as ‘Rocking Vibration’, ‘Jah Jah Dreader Than Dread’ and ‘My Girl’, as well as cool cuts of Johnny Clarke’s ‘Ride On Girl’ and Gregory Isaacs’ ‘One More Time’. The quality remains high throughout, bolstered as usual by the tough rhythms of Sly and the Revolutionaries, laid down at Channel One and mixed at King Tubby’s.

Matumbi

‘After Tonight’

(TRO 9032, 1978)

British reggae had something of a second-rate stigma about it when compared with the music emanating from Jamaica, but original British reggae combo Matumbi helped dissipate the comparison with this classic slice of lover’s rock. It was co-written by Errol Pottinger, who sang lead on the track, and musical arranger Dennis Bovell, who was the band’s guitarist, but who would later be better known as a bassist and music producer. The song has remained a perennial favourite on the ‘revival reggae’ circuit, the harmonic brilliance of the vocals and uncommon musical arrangement being key elements that set the track apart.

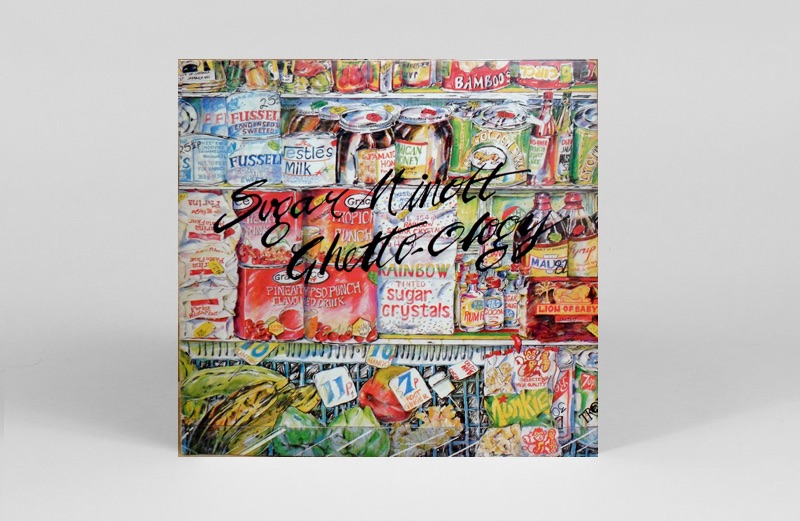

Sugar Minott

Ghetto-ology

(TRLS 173, 1979)

Lincoln ‘Sugar’ Minott got his start in The African Brothers harmony trio before going solo in the late 1970s. He helped revitalise the fortunes of Studio One by voicing new hits over vintage rhythms, but began producing his own work from 1978, since financial recompense was not always as expected. Ghetto-ology was a masterful roots album from Sugar, its rhythms laid down by uncommon 12 Tribes session players at Channel One, and voiced and mixed by Prince Jammy at King Tubby’s studio. The title track is an excellent dissection of ghetto life, with ‘Man Hungry’ and ‘Walking Through The Ghetto’ continuing to riff on the same theme. ‘The People Got To Know’, ‘Dreader Than Dread’ and ‘Never Gonna Give Jah Up’ are moving expressions of Rastafari devotion.

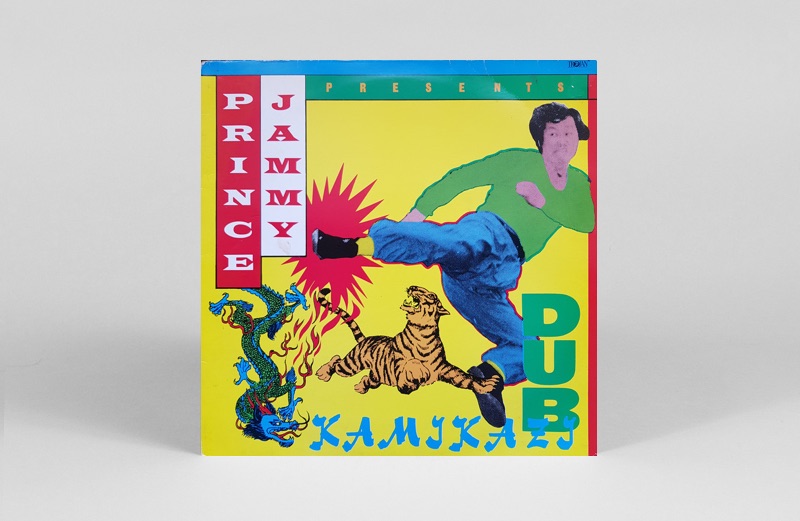

Prince Jammy

Kamikazi Dub

(TRLS 174, 1979)

Lloyd ‘Jammy’ James grew up on the same road as King Tubby in the Waterhouse ghetto, with Tubby his main mentor in music and electronics. James started a sound system in the ska years but moved to Toronto in 1969 for an extended period, returning to Jamaica in 1976 to become the chief engineer at King Tubby’s studio. Soon he began producing excellent roots reggae with Black Uhuru, The Travellers and Delroy Wilson, among many others, and his dub B-sides were always exceptional. Kamikazi Dub gathers thrilling dub counterparts to Lacksley Castell’s ‘What A Great Day’, Sugar Minott’s ‘Give The People What They Want’ and Barry Brown’s ‘We Can’t Live Like This’. With the rhythms laid at Channel One, and everything dubbed by Jammy at King Tubby’s studio, it’s a real winner from start to finish.

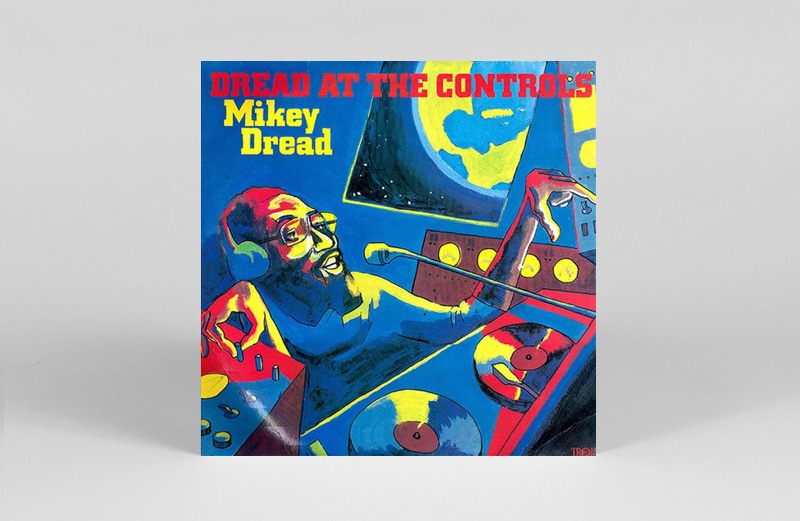

Mikey Dread

Dread At The Controls

(TRLS 178, 1979)

Michael Campbell’s love of music and interest in electronics led him to revolutionise Jamaican radio in the late 1970s with the Dread At The Controls radio show, which broadcast through the night on the government-backed JBC. A deejay with his own particular take on the art of toasting, as Mikey Dread he began voicing for producers such as Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry but ultimately concentrated on his own productions. Debut album Dread At The Controls has a lot of humour in it, with ‘Barber Saloon’ and ‘Dread Combination’ being full of jokes in Mikey’s rhyming deliveries. Recorded at Channel One, Treasure Isle and Joe Gibbs, the whole set was voiced and mixed at King Tubby’s studio, since Campbell had a close working relationship with Tubby himself.

Barry Brown

‘Living As A Brother’

(TACK 23, 1980)

Roots reggae enigma Barry Brown cut some outstanding material at the tail end of the roots reggae era, and was also part of the shift towards the dancehall style, since he first honed his singing craft on west Kingston ghetto sound systems such as Tape Tone. Inspired by Linval Thompson and Horace Andy, Brown’s fragile but forceful tenor began gracing records from 1977, once Bunny Lee began recording him. Hits followed for just about every producer of note during the late 1970s, and there were sparse, self-produced efforts too. ‘Living As A Brother’ is easily among the best of the work he recorded for Linval Thompson, being a hard-hitting treatise on why Brown deserves to be left alone by the evil forces of Babylon that seek to curtail a peaceful man’s life. The rock-solid Roots Radics rhythm is given its utmost spatial representation through the mixing skills of the young Scientist, the latest mixing talent to emerge from King Tubby’s studio.

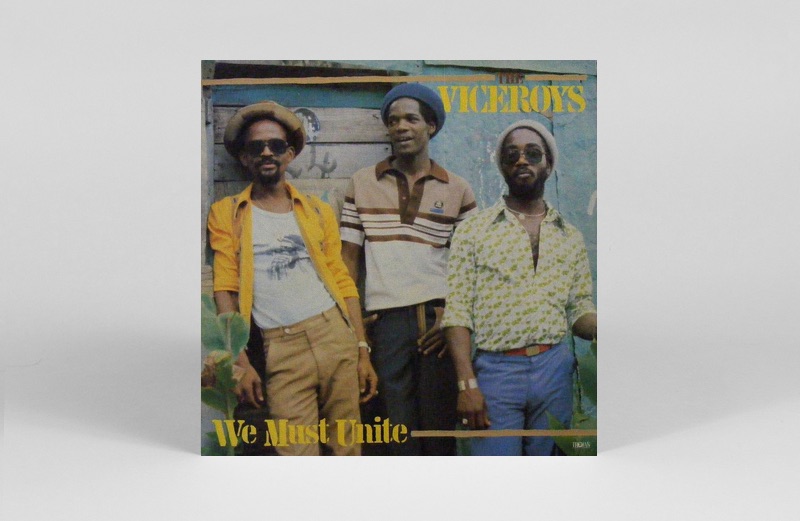

The Viceroys

We Must Unite

(TRLS 208, 1982)

Harmony trio The Viceroy have a long and complicated history. Formed in the mid-1960s, the group recorded widely for Studio One and Derrick Morgan, with sparser work for Joe Gibbs, Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry, Sir JJ, The Matador, Sidney Crooks and Winston Riley, among others. We Must Unite is the sole album they recorded with Linval Thompson in the producer’s chair, and Thompson really drew the best of their abilities, the sweet harmony sitting perfectly above the tough rhythms laid down with The Roots Radics at Channel One, voiced and mixed by Scientist at King Tubby’s. ‘Love Is A Key’, ‘My Mission Is Impossible’, ‘Rising The Strength Of Jah’, and the rousing title track are all stunners, and the whole set hangs together nicely.

Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry

‘I Am A Madman’

(TROT 9095, 1986)

Maverick dub pioneer and walking performance art piece Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry surely needs little introduction here. Suffice it to say that he began at Studio One in the ska years of the early 1960s, moved on to partner with Prince Buster and WIRL Records in rock steady and helped usher in the new reggae style in 1968. His Black Ark studio is a place of legend, but after it was trashed and burned in the early 1980s, Perry became a wandering nomad, washing up anchorless in London from 1984. This controversial autobiographical track, ‘I Am A Madman’, was recorded in London with a mixed backing band led by guitarist Mark Downie. The extended 12″ version issued by Trojan features chop-n-mix splicing from Mad Professor, making the most of Perry’s troubling proclamations.

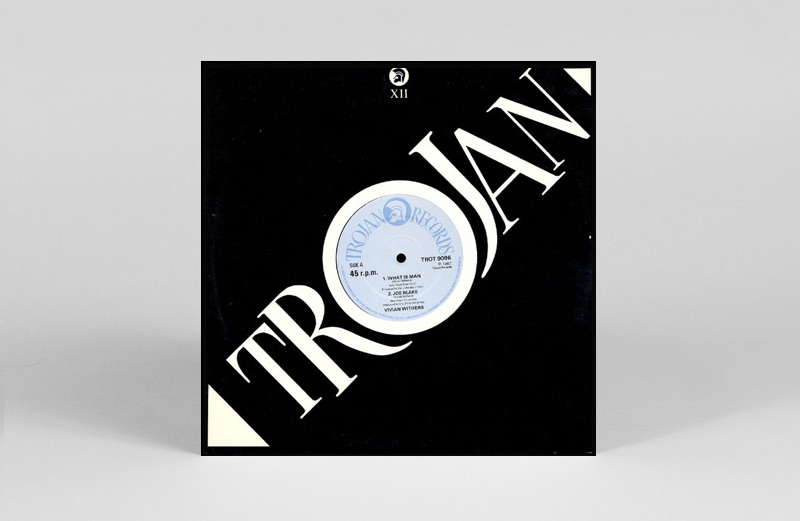

Vivian Withers

‘Hangin’ On’

(TROT 9096, 1987)

One of the most enigmatic of all British reggae artists, Vivian Weathers was closely connected to Linton Kwesi Johnson’s Poet and the Roots project, playing bass and guitar on the Virgin album Dread Beat And Blood, his chilling falsetto also leading ‘Song Of Blood’, which he co-produced. Solo album Bad Weathers did not fare well for Virgin and Island’s lover’s rock single ‘Just A Game’ led nowhere. The 12″ EP, released by Trojan in 1987 seems to have been a last gasp, with ‘Hangin’ On’ the sound of a life disintegrating, describing unpaid rent in a gloomy room peopled only by empty whiskey bottles and dirt. Since nothing has been heard of Weathers since, one wonders whether he ultimately lost his grip, crossing the unclear line to an unsound mind.

Illustration by Nick Taylor