The essential guide to Brian Eno in 10 records

Ten milestone recordings by the godfather of ambient music Brian Eno.

Words: Chris May

Until recently, aside from his early 1970s spell as Roxy Music’s flamboyant synthesiser player, the composer, musician and producer Brian Eno has favoured a generally quiet and retiring public presence. His work has attracted controversy: the genre-defining 1978 album Ambient 1: Music for Airports unleashed as much critical bile as it did praise, and 1981’s My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, a collaboration with David Byrne, attracted allegations of cultural imperialism in some quarters, and praise for weaving previously excluded traditions into rock in others. Even at the height of those debates, however, Eno mostly let his music speak for itself. He dislikes giving press interviews, and probably agrees with Frank Zappa’s observation that “rock journalism is people who can’t write, interviewing people who can’t talk, for people who can’t read.”

In the 2010s, however, Eno is breaking cover. He is in the forefront of the public debate over the dangers and benefits of digital technology, championing algorithm-driven generative music, for instance, while continuing to laud analogue-era recording values. The issue figured in the John Peel Lecture he gave on BBC radio last year.

Eno’s biggest mainstream successes have been as a member of Roxy Music and, more recently, as the producer of U2 and Coldplay, but his most enduring music may well prove to be among his many solo and collaborative recordings. These span glam rock, art rock, avant funk, electronica, ambient, fourth-world and generative music. Eno self-deprecatingly describes them as “little ships floating on a sea of indifference.”

Eno has also produced over 50 albums for other artists, from U2 and Coldplay to Laurie Anderson, Seun Kuti, David Bowie, Baaba Maal and Grace Jones. For reasons of space, these have been put aside for later consideration. Here are ten of Eno’s most essential “little ships.”

Eno

Here Come the Warm Jets

(Island, 1974)

Eno played on Roxy Music’s first two albums, Roxy Music and For Your Pleasure, before quitting the band because of his increasingly dysfunctional relationship with lead singer Bryan Ferry, who wanted to be the visual focus of the line-up, a position threatened by Eno’s neon-lit sartorialism – heavy makeup, feather boas, corsets, stack heels and all – and who, in the studio, was also less experimentally inclined than Eno.

A high-proof cocktail of glam-rock and art-rock, Here Come the Warm Jets, Eno’s first album under his own name, features Roxy Music’s Andy MacKay, guitarist Phil Manzanera and drummer Paul Thompson, and suggests how Roxy Music might have developed under Eno’s leadership. Guests include King Crimson guitarist Robert Fripp, a key Eno collaborator in the mid 1970s. Eno’s second own-name album, Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy), recorded a year later, is in a similar, though more nuanced, groove.

Fripp & Eno

(No Pussyfooting)

(Island, 1973)

Recorded between autumn 1972 and summer 1973, while Eno was still a member of Roxy Music, this collaboration with Robert Fripp proved to be more indicative of Eno’s long-term approach to music-making than either Here Come the Warm Jets or Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy).

There are two side-long tracks, co-written by Fripp and Eno, which introduce the tape-looping technique, later known as Frippertronics, co-created by Eno and Fripp with a nod to American minimalist composer and audio innovator Terry Riley. Revolutionary for its time, (No Pussyfooting) still gets under the skin. Eno’s later ventures into ambient, fourth-world and generative musics are part-rooted here.

Eno

Another Green World

(Island, 1975)

This dreamlike, mainly instrumental album is a halfway post between the looping innovations of (No Pussyfooting) and the full-on new pastures of 1978’s Ambient Music 1: Music for Airports. Eno’s melody-rich compositions tend to foreground rather than dial-down the music, thereby disqualifying it from the description “ambient”.

Fripp guests on two tracks, as does Velvet Underground violist John Cale. Eno had recorded with Cale on the live-in-London album June 1, 1974, in an art rock supergroup which also included Kevin Ayers and Nico. (Gratuitous gossip: the cover shot of that album, taken minutes before the gig began, shows Ayers and Cale in an apparently relaxed, brotherly pose. The night before, however, Cale had caught Ayers having sex with his, Cale’s, wife. The show must go on).

Brian Eno

Ambient 1: Music for Airports

(EG, 1978)

Eno used the term ambient music to distinguish it from canned background-music such as Muzak. In his liner notes for this album, he wrote that while canned music regularised environments by smothering their acoustic and atmospheric idiosyncrasies in an audio comfort-blanket, ambient music was intended to subtly accentuate those idiosyncrasies. Eno has described ambient music as “rewarding attention but not being so strict as to demand it” – a definition which also highlights ambient’s key difference to new-age music, whose lack of substance is revealed if attention is given to it.

Ambient 1 was performed mainly by Eno (Robert Wyatt guests on piano on one track and there is a female vocal-trio on three) and mainly on electronic instruments. By contrast, another recommended album in the series, Ambient 3: Days of Radiance, featured the American zither player Laraaji, with minimal sound or tape manipulation by Eno.

Brian Eno – David Byrne

My Life in the Bush of Ghosts

(Sire, 1981)

A forerunner of the so-called “world-music” which emerged later in the 1980s, the breathtakingly novel My Life in the Bush of Ghosts combines Eno’s ambient aesthetic with the culturally inclusive music of another collaborative album, Fourth World Vol. 1: Possible Musics, made by Eno with the trumpeter Jon Hassell and released in 1980.

Built on rock and funk foundations, and laced with Byrne’s singular take on gospel music, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts overlaid a variety of non-Western styles, notably from North Africa and the Middle East. Like Paul Simon’s South African-infused Graceland in 1986, the album attracted accusations of cultural imperialism from some quarters, including the Islamic Council of Great Britain, who successfully lobbied for the track ‘Qu’Ran’, featuring Koranic chanting recorded in Algeria, to be removed from reissues.

Harold Budd – Brian Eno

The Pearl

(Editions EG, 1984)

Co-written by Eno and minimalist composer Harold Budd, The Pearl can be filed next to an earlier Eno/Budd collaboration, 1980’s Ambient 2: The Plateaux of Mirror. The mix foregrounds Budd on looped and multi-tracked acoustic and electric piano, with gossamer-light background-washes by Eno on synthesisers. Co-produced with Daniel Lanois, another master of understatement, with whom Eno collaborated on the mid to late 1980s albums Apollo: Atmospheres and Soundtracks, Thursday Afternoon, Hybrid and Textures. Glistening and spacious, The Pearl still stands as a high-benchmark of minimalist/ambient music.

Eno – Cale

Wrong Way Up

(Land, 1990)

Listen / Buy

This ultra-melodic, synthesiser-cored set is perhaps closer to art-pop than art-rock, and is unusual, too, for its vocals, which Eno had largely eschewed since the late 1970s. Wrong Way Up grew out of Eno’s production of Cale’s Words for the Dying in 1989, after which Eno invited Cale to spend a month living and recording at his home/studio in Suffolk. The music is gorgeous, but the creative process was not so harmonious, as the daggers separating the topsy-turvy Eno and Cale portraits on the front cover suggest. In a press release accompanying the release, Eno answered the question “Would you ever record with John Cale again?” with the words “Not bloody likely.”

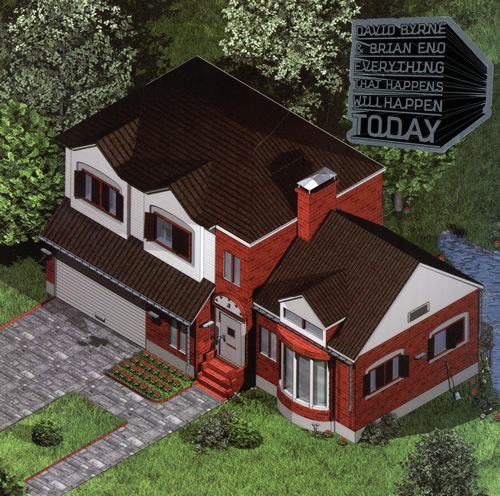

David Byrne & Brian Eno

Everything That Happens Will Happen Today

(Todo Mundo, 2008)

Another rock going on pop production, Everything That Happens Will Happen Today was the first co-headlined album Eno and Byrne had made since My Life in the Bush of Ghosts in 1981. The album explores a theme that has since increasingly occupied Eno’s attention: the benefits of digital technology versus its threat to the retention of human values in cultural creation. But this is no modishly dystopian album, instead it is uplifting and ultimately optimistic.

Fripp & Eno

The Equatorial Stars

(Discipline Global Mobile, 2014)

Another successful reunion. The Equatorial Stars – the title echoes that of Fripp and Eno’s last co-headlining album, 1975’s Evening Star – was recorded in 2004 and given CD-only release in 2005. The empathy between the guitarist and producer/keyboard player is undimmed after 30 years of, mostly, separation (the pair had worked together on some third-party productions along the way). Most of the tracks press the same, serene buttons as did (No Pussyfooting) and Evening Star. Others nudge the music towards more troubled waters or a touch of funk.

Eno – Hyde

High Life

(Warp, 2014)

One of two 2014 albums (the other is Someday World) co-headlined by Eno and Underworld vocalist/guitarist Karl Hyde. The production pays more than a nod to generative music, but the description Eno gave it in a 2014 interview was “Reickuti.” From Steve Reich, Eno said he was referencing repetition for its own sake: the idea that the more you repeat something the more your mind makes it appear to shape-shift and evolve. From Fela Kuti, he was referencing rhythmic-melodic interplay: such as the way the drum patterns played by Afrika 70’s Tony Allen implied many other parts, both rhythmic and melodic. In the band is Eno’s one-time Roxy Music colleague, saxophonist Andy MacKay, who played on Eno’s solo debut, Here Come the Warm Jets, four decades earlier. Which is where we came in.