The 14 synthesizers that shaped modern music

Originally published on FACT.

Words: John Twells

The synthesizer is as important, and as ubiquitous, in modern music as the human voice.

The concept is simple enough – a basic circuit generates a tone, and the tone can then be controlled by some sort of input, human or otherwise. It’s a concept that has provided the backbone for countless instruments over the last 100-or-so years, and like it or not, has informed the direction of modern music both in the mainstream and in the underground.

These days it’s easy enough to boot up your cracked copy of Ableton Live or Logic and open any number of VST synthesizers, giving you access to decades of technological innovation. It is however important to know how these sounds took hold in the first place, and why they were so successful. Sometimes it was simply the fact that there was no competition (the Minimoog) and sometimes the success was simply down to price and availability (the MS-20).

The following list contains a few of the key instruments that helped shape electronic music, from the obvious (the unmistakable Roland TB-303) to the obscure (the humble Alpha Juno 2). You might be surprised how many of them lie at the center of your favorite tracks.

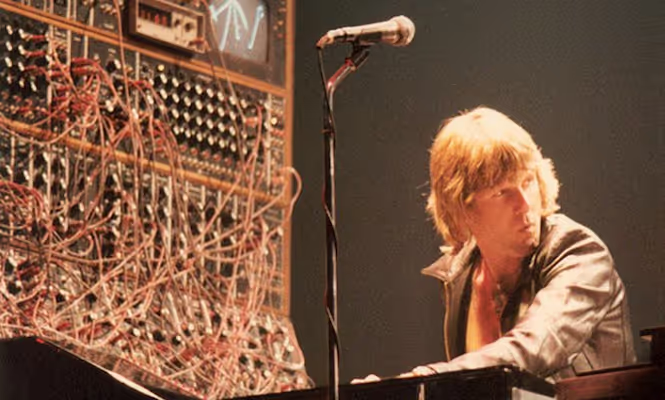

EMS VCS3

Released: 1969

Original price: £330 + £150 for the keyboard

It was designed to be cheap, portable and easy to program (or “patch”), and the Voltage Controlled Studio No.3 from British company EMS might have become the industry standard if it hadn’t been for Bob Moog’s tidier successor. Nicknamed ‘The Putney’ after EMS’s London location, the VCS3 was basically a modular synthesizer, but instead of patch cables, EMS had come up with a small (and notoriously fiddly) 16×16 matrix which was used to control the synthesizer’s internal routing. This was great for portability, but made the synthesizer incredibly unpredictable, as the different pins’ impedance would vary just enough that a patch would almost never sound the same twice.

Thanks to its uniqueness at the time (it was the first synthesizer that was truly available to the general public) and its very modest price point, the VCS3 was a massive success, lending EMS a market share that was set to rival competitors Moog and ARP. Sadly, after a number of bungled launches and a move from London to Oxfordshire, EMS hit an irreversible decline in the late 1970s and the failing company was sold off. In 1995 however, the rights to EMS were acquired by Robin Wood, who began building and selling VCS3s all over again, proving that the market for eerie sci-fi synthesizer sounds was a long way from drying out.

What did it sound like?

The VCS3 was weird, and it stands to reason that it ended up being such a science fiction standard. It was so quirky that most musicians couldn’t even fathom how to coax actual melodies out of it, prompting some to label it as a bulky, expensive effects unit. Those that persevered were rewarded, and the bizarre-sounding synthesizer was a bottomless treasure trove of peculiar pops, clangs and whines. The fact that you could play it with a joystick, a la Led Zeppelin’s John Paul Jones (the keyboard was sold separately), only added to its charm.

Who used it?

While she actually didn’t love synthesizers as much as people like to think (preferring the “musique concrete” technique), Delia Derbyshire was one of the most important early adopters of the EMS VCS3, using it prominently on her White Noise album An Electric Storm and even persuading the BBC to buy a few units for the Radiophonic Workshop. It’s hardly surprising, as she was a close friend of EMS founder Peter Zinovieff (they were both founder members of Unit Delta Plus, an organization dedicated to the promotion of electronic music), and the machine had been designed by occasional Doctor Who composer (and EMS co-founder) Tristram Carey.

The VCS3 even made it to rock studios, as bands like Hawkwind, Led Zeppelin and Pink Floyd began to experiment with electronic sounds and integrate them into their respective sounds. Hawkwind loved the shiny box so much that they named Space Ritual standout ‘Silver Machine’ after it.

Heard on:

White Noise ‘Love Without Sound’ (1969)

Hawkwind ‘Silver Machine’ (1972)

Roxy Music ‘Ladytron’ (1972)

Edgar Froese ‘Upland’ (1974)

Portishead ‘We Carry On’ (2008)

MOOG MINIMOOG

Released: 1969 (prototype), 1971 (production)

Original price: $1495

Bob Moog’s revered Minimoog was the first fully integrated synthesizer, and as such marked one of the most important developments in electronic music. Earlier Moogs were oppressively bulky and near impossible to take on tour, made up of modules that could fill a small room. They were built to order and sold as “professional audio equipment” rather than instruments, and as such were considered out of reach for most musicians and studios. In contrast the Minimoog was built for portability and was comparatively simple to use, with a selection of user-friendly knobs and switches replacing its predecessor’s clunky patch cables.

Initially the Minimoog’s layout and list of terms (‘Filter’, ‘Oscillator’ etc) confused music stores, who weren’t sure whether musicians would be able to get their heads around this new instrument, but the fact that the Minimoog is still in production over four decades later should speak for itself.

What did it sound like?

Being monophonic (meaning only one note could be played at a time), it might not have been suitable for bashing out chords, but the Minimoog’s versatility lay in its generous three oscillators and still-legendary filter. The four-pole low-pass filter is still seen as the best in its class, and is responsible for the thick, bassy throbs that have come to characterize the instrument over the last four-and-a-half decades. It’s a sound that most producers are able to fit into any track, and when you think of how an analogue synthesizer is supposed to sound, you’re probably thinking of a Minimoog.

Who used it?

A more pertinent question might be “who didn’t?”, as for a while the Minimoog was considered a crucial (if a little pricey) part of any forward-thinking musician’s arsenal. It was avant jazz vanguard Sun Ra who managed to pip his peers to the post though, as he was given the chance to borrow one of Bob Moog’s early prototypes (a Model B) in 1969. He loved the instrument so much that he never returned it, and even bought a second one when they went into production. He was spotted playing both of them at once on numerous occasions, no doubt in an effort to combat the synthesizer’s monophonic limitations.

Influential German band Kraftwerk started an electronic music revolution with their fourth (and so far most commercial) album Autobahn, and the Minimoog sat at the center of their setup, even making it to the cover image of some versions of the release. It wasn’t just experimental artists that took to the Moog either – the bassline on Michael Jackson’s world-beating ‘Thriller’ was made from two modified Minimoogs playing in unison, Hot Butter used the Minimoog in their re-recording of instrumental electronic classic ‘Popcorn’ and Keith Emerson played one on Emerson, Lake and Palmer’s acclaimed Tarkus.

Heard on:

Sun Ra ‘The Wind Speaks’ (1970)

Emerson, Lake & Palmer ‘Aquatarkus’ (1971)

Kraftwerk ‘Autobahn’ (1974)

Devo ‘Mongoloid’ (1977)

Parliament ‘Flashlight’ (1977)

ARP ODYSSEY

Released: 1972

Original price: unknown

Moog had successfully conjured up a brand new market for portable, user-friendly synthesizers, and American manufacturer ARP knew they needed to get in on the action. Their bulky 2500 and 2600 modular units were popular and incredibly widely used, but it was smaller Minimoog competitor the Odyssey that really captured the public’s imagination. The synth was basically a stripped-down version of the 2600, and turned out to be the company’s best selling synthesizer. Considered by many to be inferior to the Moog, as it only boasted two oscillators to the Minimoog’s three and was saddled with a comparatively limited filter, the Odyssey was actually the world’s first duophonic synthesizer – capable of playing two notes at once.

What did it sound like?

Early versions of the Odyssey which featured the two-pole filter (it was later replaced by a four-pole version to come up to snuff with the Minimoog) were notoriously tinny, but gave the Odyssey a character all of its own. It’s often confused with the Moog as many bands (and studios) often owned both synthesizers, but the Odyssey excelled with brassy lead sounds and the kind of resonant twangs that came to characterize the electro pop sound.

Who used it?

The synth was picked up early on by German electronic outfit Tangerine Dream, as heard on a handful of their early ’70s recordings as well as 1981’s Exit, and was also used by genre-hopping jazzer Herbie Hancock, whose track ‘Chameleon’ opens with the synthesizer’s characteristic pulse. The melody on ABBA’s cheeky 1979 hit ‘Gimme Gimme Gimme’ was also played on the Odyssey, and it’s been widely referenced as being Ultravox man John Foxx’s favourite synthesizer of all time – he used it liberally on his 1980 classic Metamatic. Thanks to its popularity, the synth could be obtained fairly inexpensively and was snapped up by a young Richard Davis, who along with Juan Atkins used the Odyssey on their early Cybotron recordings, paving the way for the electro and techno that would follow.

Heard on:

Herbie Hancock ‘Chameleon’ (1973)

John Foxx ‘Underpass’ (1980)

Peter Howell ‘Doctor Who Theme’ (1980)

Cybotron ‘Alleys of Your Mind’ (1981)

Nine Inch Nails ‘The Hand That Feeds’ (2005)

YAMAHA CS-80

Released: 1976

Original price: $6900

Beloved by synthesizer collectors, and not just because of its alarmingly high second-hand price tag, the Yamaha CS-80 was Japan’s first truly outstanding contribution to the synthesizer marketplace. Fathoms deep, alarmingly unusual (that ribbon controller?) and jam-packed with sounds that simply didn’t emanate from other, similar instruments, the CS-80 was a delightfully luxurious instrument. Even so, the high price tag and overwhelming weight of the CS-80 (it was a back-breaking 220lbs) made it a hard sell, and like many synths of the era, it was also notoriously difficult to keep in tune.

When the CS-80 had to face competition from Sequential Circuits’ Prophet V and Moog’s Polymoog in the years that followed, it was hard to convince studios to shell out the extra cash for what appeared – at least on the surface – to be an inferior instrument. The poor CS-80 was saddled with a mere 26 non-programmable presets at a time when having large banks of sounds, and being given the option to save your own, was starting to become a prerequisite.

What did it sound like?

The CS-80 was among the first ‘true’ polysynths, which meant playing chords was no problem at all, and it also boasted a feature that allowed the layering of patches, basically giving the performer two independent eight-voice selections to play with. It was also one of the first synthesizers to offer a velocity sensitive keyboard, allowing the kind of expression usually tied to ‘real’ instruments, and introduced polyphonic aftertouch. Best of all though, there was a sizeable ribbon controller on the front panel that allowed seamless control of the CS-80s various knobs. In contrast to the restricted controls on other synths, the CS-80’s ribbon allowed long, smooth pitch bends and gigantic filter sweeps, giving it a versatility that few competitors could compete with.

Who used it?

Well, given the price, bedroom producers weren’t exactly developing back problems hauling their CS-80s up a three-floor walkup, but the weighty beast did make its way to the larger studios. Stevie Wonder was particularly fond of it, apparently using it so much that he managed to break the ribbon controller. Vangelis was also a massive devotee, using it first on 1977’s Spiral and on most of his successive albums. In many ways it was his secret weapon – the unfathomably influential soundtrack to Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner was almost entirely made up of barely edited CS-80 presets (seriously), as was his chart-busting theme to Chariots of Fire.

The BBC Radiophonic Workshop also had a CS-80 in their collection for some time. Workshop technician Peter Howell was so desperate to get his hands on one of the expensive synths that he practically begged the BBC to shell out for one. Thankfully when they did, it featured on a large amount of Doctor Who’s ’80s soundtracks, and memorably was used to make the ring modulated sting sound that opened the theme music.

Heard on:

Brian Eno ‘Julie With…’ (1977)

Paul McCartney ‘Wonderful Christmas Time’ (1979)

Klaus Schulze ‘Silent Running’ (1981)

Vangelis ‘Blade Runner Blues’ (1982)

Toto ‘Africa’ (1982)

KORG MS-20

Released: 1978

Original price: $750

Not a million miles away from ARP’s huge and powerful 2600, Korg’s relatively portable MS-20 boasted a similar blend of hardwired and patchable connections. It was part of the company’s second generation of monosynths (along with its little brother the MS-10) and while its dominating appearance attracted plenty of users, many musicians were disappointed to find that it sounded absolutely nothing like the Minimoog. Instead the MS-20 was tinny and difficult-to-control, and if you didn’t know exactly what you were doing you’d often end up with unusable sludge. MS-20s and MS-10s were the kind of synths you’d be able to find in the late ’80s and early ’90s gathering dust in junk shops and at car boot sales.

It was probably this availability that prompted the synth’s renaissance, and after a glut of usage in the mid-to-late ’90s, the price of the MS-20 quite rightly rocketed. It’s been on a high ever since, garnering a software rework (with fully functional controller) and a proper analogue remake.

What did it sound like?

The MS-20 was blessed with two oscillators and two filters, which gave the synth its characteristic resonant squeal and womping low-end. It was also saddled with a fairly unique external signal processor, which allowed either the control of the synthesizer from an external sound source, or the manipulation of external sounds through the MS-20’s hardworking filters. This gave musicians the kind of options for abuse usually reserved for modular nerds or studio spods, and it’s this (and the synth’s ability to sound like hiccuping robots or a belching drain) that has seen it gain so many followers over the three decades since its release.

Who used it?

Not achieving massive popularity early on, the MS-20 was initially consigned to budget electro recordings or found haunting the noisier end of the experimental private press scene. German synthesizer fetishist Felix Kubin was gifted an MS-20 in 1980 and has been obsessed with it ever since, but this was an exceptional case.

For some reason (probably the price, let’s be honest), usage of the synthesizer seemed to bubble up in the 1990s with a surge of interest coming from France. Daft Punk used the MS-20 to craft their breakout anthem ‘Da Funk’, psychedelic pop duo Air used it to manipulate their vocals on ‘Sexy Boy’, and most famously of all, Mr. Oizo used the synth to create the bassline on Levi’s advert soundtrack ‘Flat Beat’. Alison Goldfrapp was also spotted using the synth (which she would control with her vocals) and it remained at the center of Add N to (X)’s setup for many years.

Heard on:

OMD ‘Bunker Soldiers’ (1980)

Daft Punk ‘Da Funk’ (1995)

Air ‘La Femme D’Argent’ (1998)

Mr Oizo ‘Flat Beat’ (1999)

Felix Kubin ‘Japan Japan’ (2003)

SEQUENTIAL CIRCUITS PROPHET-5

Released: 1978

Original price: $4495

A polyphonic synthesizer that was as easy to manipulate (and carry) as the hugely popular Minimoog, Sequential Circuits’ Prophet-5 quickly became an industry standard. What gave the Prophet a boost was that it included a patch memory – something sorely lacking from direct competitor the Yamaha CS-80 – allowing users to store their sounds rather than relying on preset settings or writing down the positions of each switch and knob on supplied printed sheets. It spawned a bigger brother in the Prophet-10, but what that machine gained in polyphony it lost in reliability, and the machine was notorious for overheating and conking out mid-session. Far more popular was the Prophet-5’s little brother, the cheeky and popular Pro-One.

Sadly Dave Smith’s company Sequential Circuits shut down in the late ’80s as digital synthesizers started to dominate, but the legend of the Prophet-5 continued to grow. Smith rebooted his line establishing Dave Smith Instruments in 2002, and he celebrated its 30th anniversary of the Prophet-5 in 2007 with an acclaimed new version, the celebrated Prophet ‘08.

What did it sound like?

It’s not surprising that the Prophet-5 became so widely used on movie soundtracks, as the spooky analogue textures were perfect for the kind of unsettling chords that backed horror and sci-fi films in the early ’80s. It wasn’t just a functional workhorse like the CS-80 though – the Prophet could also be coaxed into making bellowing experimental sweeps and rumbles thanks to its innovative Poly Mod feature, which allowed modular-style routing of its various generators and oscillators.

Who used it?

Like the Minimoog before it, the Prophet-5 was a market leader and its hefty price tag didn’t prevent it from being extremely widely used. Film composers quickly picked up on the synthesizer, probably because it was possible to achieve so much with a single piece of equipment. John Harrison used only a Prophet-5 and a piano to record his acclaimed score to 1982’s horror anthology Creepshow, and John Carpenter quickly fell in love with the synthesizer after being introduced to it by Alan Howarth while working on Escape From New York.

Pop music loved the Prophet too – it was all over Michael Jackson’s Thriller, and a few years later could be found on Madonna’s self-titled debut and its follow-up Like A Virgin. The fact that it became such a studio staple no doubt led to the Prophet’s use on early West Coast rap records – Dr. Dre was a fan, and Too $hort used the Prophet (along with a Roland TR-808 drum machine) to put together his stark, influential debut album Born To Mack.

Used on:

John Carpenter & Alan Howarth ‘Escape From New York’ (1981)

Talking Heads ‘Burning Down the House’ (1983)

Madonna ‘Lucky Star’ (1983)

Too $hort ‘Freaky Tales’ (1987)

Radiohead ‘Everything in its Right Place’ (1999)

FAIRLIGHT CMI

Released: 1979

Original price: $27,500

Synthesizers don’t get much more legendary than the Fairlight CMI, and it sported a legendary price tag too. When it was released in 1979 it cost as much as a detached house, but that didn’t stop studios and the era’s stars tripping over each other to acquire one. The CMI was developed in Australia by Peter Vogel and Kim Ryrie as a development of their earlier experimental synthesizer the Qasar M8. They had wanted the M8 to be capable of modeling a waveform in real time but were hampered by lack of raw processing power, so the duo resorted to sampling instead. Thus the CMI was born and was the first sampling synthesizer, meaning it could take recorded sounds and map them across the keyboard. It was also bundled with a killer sequencer and a light pen that allowed touch-screen style control back in 1979 – talk about taking a step into the future.

What did it sound like?

It was a sampler, so technically the CMI could sound like anything you wanted it to (just check this video of Peter Gabriel synthesizing the smashing of a TV screen) but it still retained a certain special characteristic. These days its chirpy, short sound embodies the ‘80s, and it sounded that way for a reason – the sampling memory was short, and the quality wasn’t particularly high (8 bit at 16khz on the CMI Series I), so small, crunchy staccato sounds tended to work a lot better than long phrases. The ability to draw waveforms into the computer and edit previously saved waveforms was groundbreaking too, but typically most producers stuck to the (admittedly pretty great) pre-bundled sounds.

Who used it?

Ex-Genesis frontman Peter Gabriel was the first lucky customer to purchase a CMI, and he liked it so much that he coaxed his cousin Stephen Paine to market the instrument in the UK. The second unit was sold to Led Zeppelin’s John Paul Jones, and word began to spread across the Atlantic of the quirky futuristic studio enhancer. The first American adopters were Herbie Hancock (who famously demonstrated the synth on an episode of Sesame Street and used it to craft his anthemic ‘Rockit’) and Stevie Wonder, but the synthesizer was probably most widely recognized for being used by Jan Hammer in the creation of the Miami Vice theme tune. The CMI was such a novelty that Hammer was even filmed playing it in the song’s video, while of course escaping from Crockett on a helicopter – this was the ‘80s after all.

After being impressed by Peter Gabriel’s model, Kate Bush was another early CMI devotee, and she was the first musician to play the CMI on an album, making it a centerpiece of her 1980 full-length Never For Ever. It was with 1985’s Hounds of Love, however, that she really made use of it, allowing the CMI to influence the album’s conceptual and experimental sound.

Used on:

Peter Gabriel ‘Shock the Monkey’ (1982)

Herbie Hancock ‘Rockit’ (1983)

Jean-Michel Jarre ‘Zoolook’ (1984)

Jan Hammer ‘Miami Vice Theme’ (1984)

Kate Bush ‘Running Up That Hill’ (1985)

PPG WAVE

Released: 1981

Original price: $7,000

Following interest generated by the complex but unique Wavecomputer 360, PPG’s Wolfgang Palm developed the Wave, a synthesizer that combined the Wavecomputer’s innovative wavetable synthesis with the filters and envelopes usually associated with more traditional analogue synthesizers. Early on, the Wave achieved success simply because it didn’t sound like anything else on the market, but its massive price tag (Palm was looking to compete with the similarly unaffordable “workstation” the Fairlight CMI) slowed down sales as comparatively affordable FM and wavetable synths such as Yamaha’s DX7 and Ensoniq’s ESQ-1 hit the market and went on to dominate. While the company shut down in 1987, the core of the Wave was stripped out to form the backbone of Waldorf’s cheaper Microwave in 1989, and the Wave’s lifespan was surprisingly extended.

What did it sound like?

Boasting eight voices of polyphony, the PPG Wave was a go-to for any musicians wanting to create luscious sci-fi textures or rich brasses, but also managed plenty of pressure in the low end. At the time it sounded totally unique, as the complicated wavetable synthesis offered sounds that were a million miles from traditional analogue selection of sine, saw, triangle and square waves. The Wave’s learning curve was high, but those that managed to master its wavetable synthesis could create unparalleled, harmonically unusual sounds that made the PPG stand out as such a celebrated oddity.

Who used it?

German electronic music pioneers Tangerine Dream were so desperate for new sounds that they actually funded PPG, and of course beta-tested pretty much everything that made it out of Wolfgang Palm’s lab. The Art of Noise’s Anne Dudley was also an early adopter, and managed to bag a lesser-seen Wave 1 – a model that never actually reached the public – which she kept long after its successors had been released, using it on countless recordings. It was also popular in some of the larger studios, and ended up being used by David Bowie, Steve Winwood and Trevor Horn (in his work with Frankie Goes to Hollywood). Funnily enough, the Wave’s quirky synthetic sounds even fascinated jazz innovator Miles Davis, who heard music store employee Adam Holzman playing the synthesizer and invited him to join his band for a series of sessions.

Heard on:

ABC ‘The Look of Love’ (1981)

Alphaville ‘Sounds Like A Melody’ (1984)

Ultravox ‘Lament’ (1984)

Tangerine Dream ‘Poland’ (1984)

Miles Davis ‘Rubber Band’ (1985)

ROLAND TB-303

Released: 1982

Original price: $395

One of the most recognizable synthesizers of all time, it’s hard to believe that Roland’s Transistor Bass model 303 was initially a massive flop. The problem was that Roland marketed the little grey box as a virtual bassist for rock bands lacking the crucial fourth member or solo artists desperate for cheap accompaniment. Sadly the 303 never had the chops to compare to a real bass, and guitarists were more likely to be amused by the weedy bleeps than they were to shell out their hard-earned cash to purchase a unit. Thankfully the TB-303’s failure was also the reason for its success, as cash-strapped Chicago house producers, eager to create dance music on a budget, managed to exploit the synth’s inadequacies and inadvertently kick off an acid obsession that lingers to this day.

The TB-303 was only in production for a little over a year and a half, and Roland shipped just 10,000 units, which is why getting hold of one of the initially cheap synths now will cost you a princely sum. Roland have tried to re-create the machine a number of times, most recently with the AIRA TB-03, but have never quite managed to better the original’s unique squelch.

What did it sound like?

The 303’s big selling point was that it was blessed with an idiot-proof 16-step sequencer, allowing the incredibly easy programming of just the kind of simple basslines and leads you’d need for floor-filling dance music. As for the sound itself, it hardly needs an introduction – it’s acid house.

Who used it?

If you were making acid house in the late ’80s and early ’90s, you needed a TB-303, simple as. It would be wrong to assume that this was the first time they were used however; Indian producer Charanjit Singh used the 303 almost accidentally when he created 10 Ragas To A Disco Beat back in 1982. Electro-influenced hip hop producers were also quick to pick up on the sound, with Ice-T and Mantronix both using the 303 in mid-’80s productions. But it was Chicago outfit Phuture who popularized the little gray box, with 1985′s ‘Acid Tracks’ doing the rounds thanks to support from Ron Hardy. It ended up on gigantic records from 808 State, A Guy Called Gerald, Virgo, Adonis and more, and then later on made up the backbone of Richie Hawtin’s early career under the Plastikman moniker. Josh Wink shoved one through distortion on 1995’s ‘Higher State of Consciousness’ and Fatboy Slim declared ‘Everybody Needs A 303’ on his debut single, released in 1996. Since then the 303 has become more and more difficult to obtain, remaining a holy grail amongst electronic music producers.

Heard on:

Charanjit Singh ‘Raga Bhupali’ (1982)

Orange Juice ‘Rip it Up’ (1983)

Phuture ‘Acid Tracks’ (1987)

A Guy Called Gerald ‘Voodoo Ray’ (1988)

Plastikman ‘Plasticity’ (1993)

ROLAND SH-101

Released: 1982

Original price: $495

One of the simpler synthesizers on the list, the SH-101 was Roland’s final monosynth and was their attempt to hit the mass consumer market with a keyboard that looked the part and was incredibly easy to use. It came in three colors (gray, blue and red) and had the option of a ‘cool’ handgrip and strap, allowing the performer to play the synth like a guitar – an attempt to appeal to young synth pop bands who might not yet have the funds for a more established instrument.

As the larger and more acclaimed synthesizers began to get swept up by collectors and eager musicians with deep pockets, the SH-101 became a go-to for young dance music producers and quite rightly took its seat at the table of rave. Easier to play than the fiddly (and almost impossible to program) MC-202 and more instant than the TB-303, the 101 could do a great deal with a minimum amount of effort, and as such slowly but surely began to catch on.

What did it sound like?

The SH-101 didn’t sound a million miles from Roland’s massively influential TB-303, which is no doubt why it was snapped up early on by bargain-hunting techno producers. It had the same internal circuitry as the MC-202, and was capable of thick chunky basses and resonant, zappy lead sounds. It was also quite easy to mangle, which made the synthesizer very attractive to experimental electronic music producers of the late ‘90s and early ‘00s.

Who used it?

It was cheap as chips and didn’t do a great deal that the fancier Minimoog didn’t (with bells on), so the SH-101 didn’t end up in the high end studios and therefore wasn’t on quite the spread of pop tracks you might expect, but its cost made it valuable among less mainstream artists. Manchester techno innovator A Guy Called Gerald used one on 808 State’s influential first album Newbuild, and kept it around when he recorded solo acid hit ‘Voodoo Ray’, twinning the synth with the TB-303.

Aphex Twin was also a fan, and while it’s not clear which tracks actually featured the SH-101 (the intro to ‘Polynomial C’ is our best guess), he went as far as to give his Universal Indicator Green 12” the catalogue number SH-101. He wasn’t the only Warp artist to hammer Roland’s cheap monosynth – Boards of Canada used it to bash out the melodies of their breakthrough full-length Music Has The Right To Children, and of course drenched it in reverb so cavernous that you could barely recognize it. Portishead’s Adrian Utley was also a fan, and revealed to Sound On Sound in 1994 that although the intro to ‘Mysterons’ is often mistaken for a theremin, it was actually the SH-101 all along.

Heard on:

808 State ‘Narcossa’ (1988)

Robert Hood ‘SH.101’ (1994)

Portishead ‘Mysterons’ (1994)

Boards of Canada ‘Roygbiv’ (1998)

Joker & Ginz ‘Re-Up’ (2009)

YAMAHA DX7

Released: 1983

Original price: $2000

Yamaha’s ugly-looking DX7 was, even at the time, massively successful. It was the first digital synthesizer most musicians ever came in contact with, and its range of preset sounds – from convincing electric piano emulation to its familiar glassy pads – was instantly successful with pop producers across the world.

Sadly, and unlike most of the other entries on the list, time hasn’t been kind to Yamaha’s popular FM flagship. While it spawned plenty of spin-offs in the DX series (most visibly the popular TX81Z and Derrick May’s beloved DX-100), as more and more fans have gravitated towards analogue sounds, the interest in FM synthesis has dropped off. Listen carefully and you’ll hear a revival in the making (Night Slugs are definitely fans), but FM synthesizers still don’t pull in the kind of after-market prices that you see attached to their analogue brethren.

What did it sound like?

Being digital, the DX7 lacked the warm, fuzzy sounds of its analogue predecessors and was, in contrast, pretty chilly. Glassy, harsh digital sounds made up most of the presets, and the synthesizer was so damned hard to patch without any knobs and sliders that most producers simply let them be. Ambient music egghead Brian Eno was one of the only musicians who really got his head around the DX7’s complex submenus and LCD displays, and managed to actually make it sound blissful and decidedly pillowy on 1983’s Apollo.

Who used it?

Brian Eno was such a fan of the DX7 and its shonky frequency modulation synthesis that he bought a fleet of them. In a 2004 interview he claimed to have seven, which seems to us like overkill, but it is Eno, and he did manage to shoehorn the DX7 into records by U2 and Coldplay.

It was such a regular part of home and professional studios that its relatively small selection of presets became regular fixtures on mainstream radio. BASS 1 was used on A-ha’s ‘Take On Me’, Kool & The Gang’s ‘She’s Fresh’ and Kenny Loggins’ ‘Danger Zone’ (among others) and the ubiquitous E PIANO 1 (possibly the DX7’s greatest legacy) was popularized by Phil Collins, Luther Vandross, Billy Ocean and far too many others to mention.

Heard on:

Brian Eno ‘An Ending (Ascent)’ (1983)

Harold Faltermeyer ‘Axel F’ (1984) – marimba

This Mortal Coil ‘Barramundi’ (1984)

Kenny Loggins ‘Danger Zone’ (1986)

Enya ‘The Celts’ (1987)

ROLAND ALPHA JUNO

Released: 1985

Original price: £575-799

The successors to Roland’s moderately successful Juno series of synths – ranging from the pre-MIDI Juno 6 and Juno 60 to the all-conquering Juno 106 – the Alpha Junos felt slightly out of time. The synths used digitally controlled oscillators (DCO), which stabilized their voltage-controlled predecessors’ tendency to drift off key, and were loaded with high quality presets. The Alpha Juno 1 and 2 (and rack model the MKS50) were Roland’s last stab at analogue synthesis as the rest of the world moved towards the cheap and cheerful sound of the DX7 and Roland’s own JX3P. Unsurprisingly the synthesizers made hardly a dent on the scene, viewed as too expensive and difficult to patch, and as with so many of Roland’s commercial failures before them, were swiftly seen as an absolute bargain for a legion of thrifty ’90s techno producers.

What did it sound like?

There’s only one sound you need to thank the Alpha Juno for and that’s the legendary hoover sound. A simple, seemingly inoffensive preset called ‘WhatThe’, it was actually programmed as a joke (hence the name) by technician Eric Persing, but was picked up on by techno producer Joey Beltram in 1991 and a new obsession was born. It wasn’t that another synth couldn’t have produced a similar sound – a brief check online reveals countless guides – but the Alpha Juno hoover just sounds so right. For a while it was as pervasive as the TB-303, and nothing except the original would really cut the mustard – the inclusion of a giant dial (known as the “Alpha Dial”) on the front for programming and filter sweeps was the icing on the cake.

Who used it?

The Alpha Juno was never ‘cool’, so you won’t see scores of artists singing its praises (it’s no MS-20), but it was on a surprising amount of records at the time. After Joey Beltram and friends kicked off a the trend with ‘Mentasm’ in ’91, Human Resource put the ‘WhatThe’ preset into the charts with awkward rap-techno hit ‘Dominator’. Most notably however, Brit ravers The Prodigy hit the hearts and minds of a generation of pill-munchers with their controversial single ‘Charly’.

In recent years the Alpha Juno’s hoover sound has enjoyed an odd resurgence, and although it’s hard to tell whether the producers responsible are using samples or something else altogether, the unmistakable ‘WhatThe’ patch has shown up in Rihanna’s ‘Birthday Cake’, Lady Gaga’s ‘Bad Romance’ and Rita Ora’s ‘R.I.P’. Hoover for life.

Heard on:

Second Phase ‘Mentasm’ (1991)

DJPC ‘Inssomniak’ (1991)

Human Resource ‘Dominator’ (1991)

The Prodigy ‘Charly’ (1991)

Altern-8 –E-Vapor-8 (1992)

KORG M1

Released: 1988

Original price: $2166

In an industry that typically viewed a successful synthesizer as selling in the tens of thousands, the Korg M1 surpassed all expectations when it notched up sales of over a quarter of a million units. It’s still the most popular synthesizer of all time, and as such was absolutely unavoidable in late ‘80s and early ‘90s pop, rock, and of course, stock music.

The reason it was so successful is pretty simple – you got a hell of a lot for your money. At over $2000 the M1 wasn’t cheap, but offered sampling, synthesis, a plethora of effects and even an onboard sequencer. It was hardly surprising when people began to refer to the machine as a ‘workstation’, as before the irresistible rise of Cubase VST and Logic Pro, the M1 was about as close as you could get to something that would literally handle everything for you in one box without having to remortgage your house.

What did it sound like?

It sounded like the early ’90s, pretty much, and that’s because you heard it on everything, from adverts to TV shows to mainstream chart hits. The M1 came with a preset bank of 100 multisounds and 44 drum and percussion samples, and each sound was rinsed by producers across the globe. They were wonderfully, endearingly wonky, ranging from pan flutes and kalimbas to the widely overused acoustic piano and woozy strings, and each one managed to sound simultaneously realistic and synthetic all at once. The 4mb of sampling memory might sound like a tiny amount now, but at the time managed to pack quite a punch.

Who used it?

Whether you’re aware of it or not, you’ve heard the Korg M1. Its versatility and simplicity meant that it was picked up by musicians and studios large and small, and it didn’t take long for the sounds to start appearing in the charts. Madonna’s ‘Vogue’ popularized the M1’s now-legendary “Piano 8” preset, making it an instant legend in house music circles (along with the similarly ubiquitous “Piano 16”), while “Organ 02” was used liberally in Robin S’s ‘Show Me Love’, a track that’s currently doing the rounds thanks to Kid Ink and Chris Brown’s ratchet rework. The preset sound that everyone can really identify however is “SlapBass”, which producer Jonathan Wolff used to create the Seinfeld theme – thanks for that, man.

Heard on:

Madonna ‘Vogue’ (1990)

Snap ‘Rhythm is a Dancer’ (1992)

Robin S. ‘Show Me Love’ (1993)

Jay Z ‘Money, Cash, Hoes’ (1998)

Bon Iver ‘Beth/Rest’ (2011)

KORG TRITON

Released: 1999

Original price: £1799

The deluxe follow-up to Korg’s popular Trinity (which itself followed the unfathomably popular M1), the Triton offered another glossy catch-all solution for studios looking to achieve a pop sound without paying pop money. The Triton offered more polyphony than its predecessor and an improved sampler, but on its release was criticized for its cheap sounding samples and low-functioning sequencer. This didn’t stop its domination though, and the Triton became just as much of a studio staple as its predecessors.

What did it sound like?

At this point in the development of synthesizers, the endearing limitation of early analogue instruments had been snuffed out in favor of feature-heavy virtual computers that could do everything you needed (and more), and in doing so they typically lacked a specific sound or character. Of course, the masses of samples and soundbanks that made up the Triton’s sound library certainly had a particular ring to them, and you can’t listen to early ‘00s rap and R&B without hearing one or two of the Triton’s unusually dry percussive rattles or pseudo-live instrumental snaps.

Who used it?

When you talk about the Triton it’s hard not to mention Timbaland and the Neptunes, but that’s not the whole story. While the Neptunes did indeed use the Triton on many occasions (‘Grindin’’s influential beat is a sequence of Triton presets that actually sit next to each other in the sound bank), it’s the Korg 01/W that was responsible for their signature plucked guitar and clavinet sound. Similarly, Timbaland was more regularly spotted using the Ensoniq ASR-10, but definitely put the Triton to work on a number of occasions, mostly thanks to co-producer Danja’s fondness for the workstation.

Over in the UK, garage producers quickly picked up on the Triton’s accessible, smooth selection of samples – Artful Dodger’s Mark Hill used one in his productions for Craig David, and before long the Triton’s sounds were all over the scene. Grime originator Wiley no doubt had his ear to the ground, and he used the now legendary ‘Gliding Squares’ preset to create the influential bassline on innovative grime jump-off ‘Eskimo’.

Heard on:

Wiley ‘Eskimo’ (2002)

Clipse ‘Grindin’ (2002)

The Game ‘Put You On The Game’ (2005)

Busta Rhymes ‘Touch It’ (2006)

T.I ‘Hurt’ (2007)