The making of Condesa’s beautiful bespoke rotary mixers

Rotary connections.

Condesa is an Australian audio company specialising in hand-made rotary mixers. Cased in local hardwood and Tasmanian oak, Condesa’s Carmen and Lucia models have something of the Linn Sondek LP12 turntable about them – a vintage design standard synonymous with refined analogue sound.

As well as tapping into what Condesa founder Mehdi El-Aquil calls a backlash against “iPod audio”, the company has joined a growing number of independent audio makers servicing the worldwide DJ community (including the likes of Marcellus Pittman, Sadar Bahar and John Gomez) who demand a little more from their equipment. Earlier this year, they debuted a limited edition collaboration with Edinburgh-based electronic label Firecracker, encased in an intricate comic-book, wood-cut design emblematic of a label that has always put hand-made artwork first.

The rest of the time, the fact that Condesa makes every mixer by hand and to order allows Mehdi to nimbly meet specific design demands, and put the emphasis on the craftsmanship that has infiltrated a new wave of makers of turntables, speakers, and records themselves.

Like all things analogue though, the term ‘rotary’ comes with various preconceptions and a whole heap of cultural baggage. Helping unpack exactly what goes into making the mixer, we asked Mehdi to break down exactly what sets Condesa apart and why he thinks rotary is making a come back.

Give us a bit of background to Condesa, when did you start the company?

We started around 5 years ago. I’d had previous experience building vintage-style pro audio equipment for studios and musicians, so this was a great foundation for building the Condesa products. I wanted a proper rotary DJ mixer for myself, so I decided to make a few, keep one and sell the others and it slowly blossomed from there.

What makes a Condesa so different to the other rotary mixers out there?

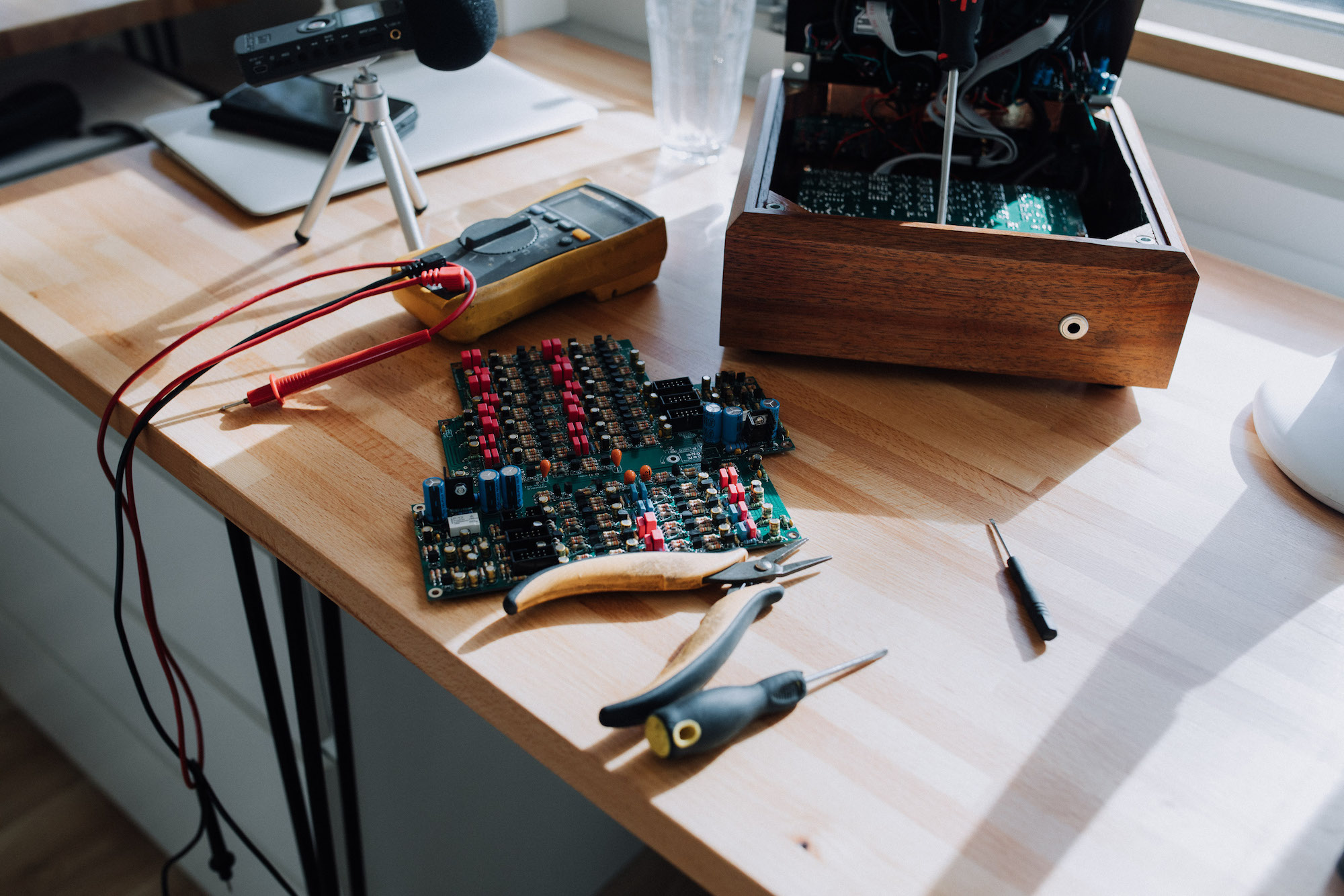

The Condesa mixers are visually quite different, all the desktop units are completely framed in wood rather than a metal box with screw on wooden side panels. We offer anodised black aluminium or brushed stainless steel panels on most of our mixers. Nearly all of our audio circuits are discrete components, we avoid using IC technology (micro chips), resulting in a distinct Condesa sound.

I imagine building each mixer from scratch takes time?

The mixers take between two and three-and-a-half full days work (model dependent) from beginning to completion. The wait time is due to the amount of mixers on order at any one time – we don’t want to rush the builds and lower the quality. The metal and wood both have lead times of about four weeks so we have to try to avoid running out of stock. We now have an expanded team and are able to build them quicker without effecting the quality.

What are the most important aspects of the design for you?

The mixers are designed around the control panel before we consider anything else. The electronics are built around the controls (not vice versa). Spacing and logical layouts are important as I want the owner to not have to think about where a control is; it should become an instinctive action. Our approach to designing a mixer is to make an instrument for playing music through.

In that case, let’s get a little bit technical. What’s the difference between a discrete circuit and the typical integrated circuits found in most club-ready mixers?

There are lots of arguments for both ways of building audio circuits and I think it comes down to the design of the circuit.

A discrete circuit is a circuit that only uses individual parts to achieve its purpose (no integrated circuits are used). ICs (integrated circuits) can be very convenient, cheap & easy to implement in audio circuits. We take the more complicated route to good sound.

Inside an average IC analogue DJ mixer the sound can pass through 15-20 IC stages from input to output. I believe that this can have a negative degrading effect on the sound quality.

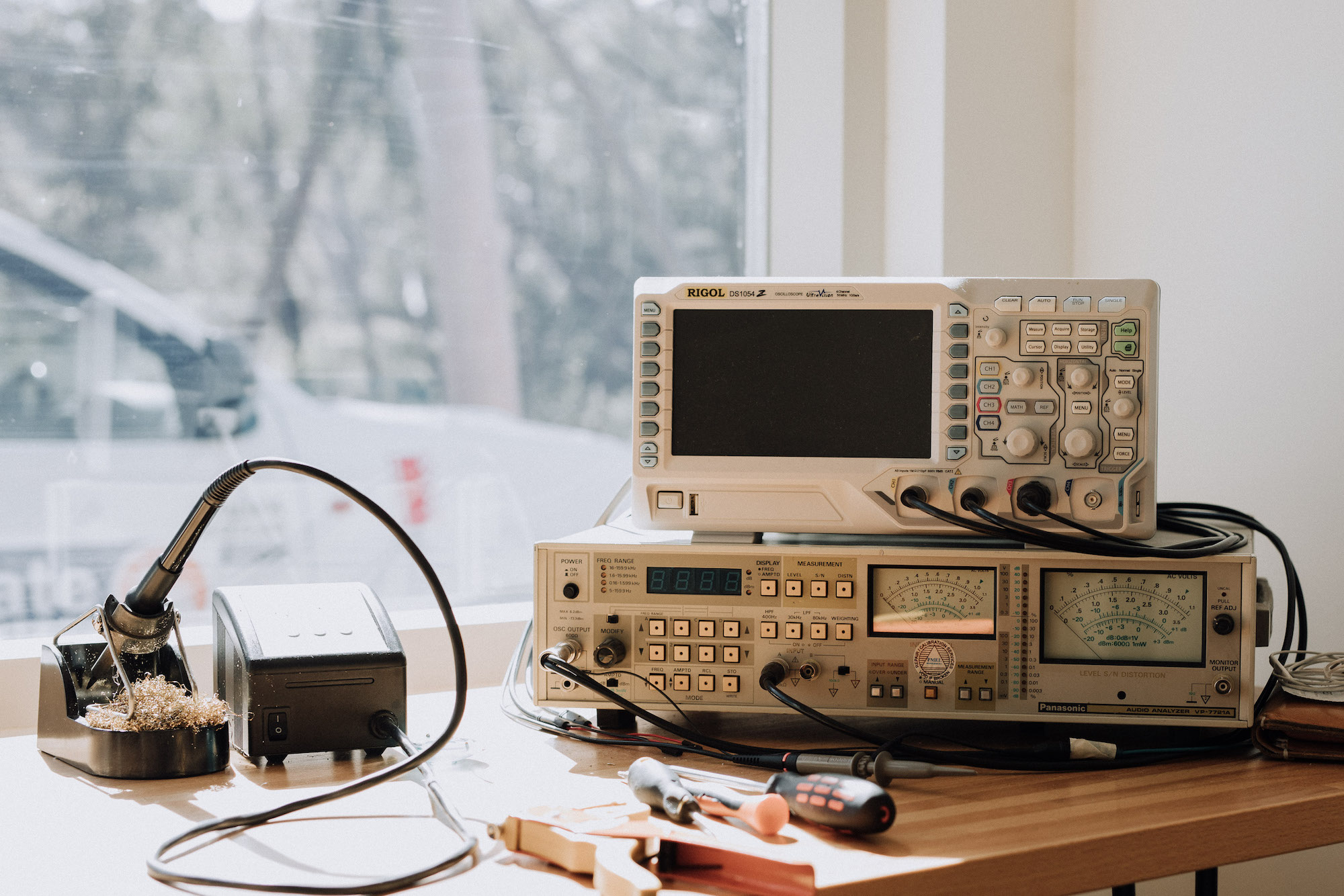

I think picking specific parts that are best suited for audio in as well as a simple audio path all help to achieve the Condesa sound. Sound and mix testing is important too, as we can’t just rely on measurements.

With our circuits we aim for very good frequency response, low noise and low distortion.

Finally, rotary mixers have become more prominent in recent years, with new companies like Condesa developing bespoke products that give the sense of offering superior sound to line-in digital mixers. What is it that makes an analogue rotary special in your opinion? Is there any point talking about which is superior?

I think the rise of the rotary mixer, and all the new analogue audio equipment, is to do with a bit of a backlash against iPod audio, and that the bigger electronic manufactures are producing DJ products that can seem generic.

A digital mixer, with all the sound manipulation tools you could ever want, seems very attractive in theory and they can be very useful as a performance tool, but I think the sound can seem sterile, clean and sometimes harsh (especially with digital media). The tactile experience isn’t the same as having true analogue controls under your fingers. Some of the most overlooked issues with digital mixers for me are the way that the channels are mixed (the digital emulation of blending the signals), the fader curve and the lack of dynamics.

I think if you are investing in records, have a good amp and speakers, then it seems logical to get a high quality analogue mixer. I’d say it comes down to personal choice, but I prefer an analogue sound path.

Find out more about Condesa and order your own here.