Afro Avant-garde: The essential Art Ensemble of Chicago in 10 records

With almost half a century of work to sift through, the oeuvre of windy city’s stalwart avant-garde jazz collective is introduced by Todd Jenkins and broken down into a modest list of ten essential albums.

Words: Todd S. Jenkins

Beginning in the mid-1960s, the Art Ensemble of Chicago was one of the premier free jazz ensembles to emerge from the crucible of Chicago’s improvised music scene. Their fusion of various jazz and pre-jazz traditions – minstrel fare, ragtime, swing – with African and European elements, theater, and far-reaching improvisation changed the landscape of modern music. A true collective, the Art Ensemble gave ample room to the playing and composing abilities of each member while retaining a unique, instantly identifiable sound that heavily influenced what followed in their wake.

The Art Ensemble had its earliest roots in pianist Muhal Richard Abrams’ Experimental Band, a (sadly unrecorded) rehearsal group dedicated to exploring the compositional ideas of young Chicago musicians. Three of these intrepid creators, saxophonists Roscoe Mitchell and Joseph Jarman and bassist Malachi Favors, were among the first members of Abrams’ Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) upon its inception in 1965. Favors, the elder statesman of sorts, had already been playing in area jazz ensembles since the mid-1950s; Jarman and Mitchell met one another in the music program at Wilson Junior College before each did a stint in the military.

Trumpeter Lester Bowie, a founding member of St. Louis’ equally ambitious Black Artists’ Group (BAG), relocated to Chicago in 1966. He almost immediately made Mitchell’s acquaintance, and the two began exploring new musical horizons together within the AACM. Bowie and Favors were in the band for Mitchell’s album Sound (Delmark, 1966), the first recording from the AACM stable. The following year, Bowie led a session entitled Numbers 1 & 2 (Nessa, 1967) with Mitchell, Favors, and Jarman. Drummer Philip Wilson was another frequent partner, although never a formal member of the Art Ensemble as it evolved.

The four-man ensemble of Bowie, Jarman, Mitchell, and Favors, dubbed the Roscoe Mitchell Art Ensemble, worked together for two years before moving to Paris, where they hoped that European audiences would be more receptive to their experiments. Gradually the AEC style grew and matured: masses of reeds from the full saxophone and clarinet families; washes and torrents of percussion from the myriad “little instruments”, drums, gongs, and reed flutes that echoed everything from insect choruses to full African dance rhythms; humorous digressions between simple themes and fiery solos; tribal garb and face paint; and, on top of it all, the full, resonant blare of Bowie’s trumpet.

After finding their niche in Paris the band met Don Moye, a self-styled “sun percussionist” and kindred spirit who became their regular drummer. Now officially named the Art Ensemble of Chicago, between 1969 and 1971 the group recorded more than twelve albums’ worth of material, released at intervals on both European and American labels. They became festival favorites and a powerful influence on native European improvisers and expatriate Americans and Africans who recognized the audacious brilliance of their music.

In 1971 the five men returned to Chicago, prepared to find their place in the now-burgeoning free music scene across America. Signed to Atlantic Records, they quickly built an audience with recordings that were just accessible enough for mainstream jazz listeners while pushing the known boundaries of group improvisation and composition. In 1978 they formed their own AECO label to issue both solo and ensemble recordings, and shortly thereafter the Art Ensemble signed with the hugely influential German label, ECM. That association further widened their audience base, bringing multiple awards, impressive record sales, and worldwide tours.

The Art Ensemble’s demise in the 1990s was perhaps inevitable, given changes in critical tastes and the simple passage of time. When Jarman retired from music in 1993 to open a Buddhist dojo, the group continued as a quartet. Bowie, who had founded his own Brass Fantasy project on the side, died of liver cancer in 1999 and was briefly replaced by saxophonist Ari Brown. The Art Ensemble recorded Tribute to Lester (ECM, 2001) as a trio, and Jarman returned to the fold for The Meeting (Pi Recordings, 2003). Malachi Favors’ passing in 2004 dealt another blow to the band’s foundation. A series of personnel changes followed, with trumpeter Corey Wilkes and bassist Jaribu Shahid being the most regular additions. Despite the loss of two core members, the impact and legacy of the Art Ensemble of Chicago continues to be felt in the 21st century.

Art Ensemble of Chicago

The Art Ensemble: 1967/68

(Nessa, 1993)

Producer Chuck Nessa, an important figure in documenting the group’s early days, compiled this fascinating collection of tracks by the Roscoe Mitchell Art Ensemble (before “of Chicago” was appended to the name). Much is drawn from the albums Old/Quartet, Numbers 1 & 2, and Congliptious, with extra goodies added. The core quartet is augmented by drummers Thurman Barker, Philip Wilson and Robert Crowder on various tracks, and bassist Charles Clark on an early version of Favors’ ‘Tutankhamun’. A wonderful window into the band’s development, as the use of odd instruments and sound devices is already evident.

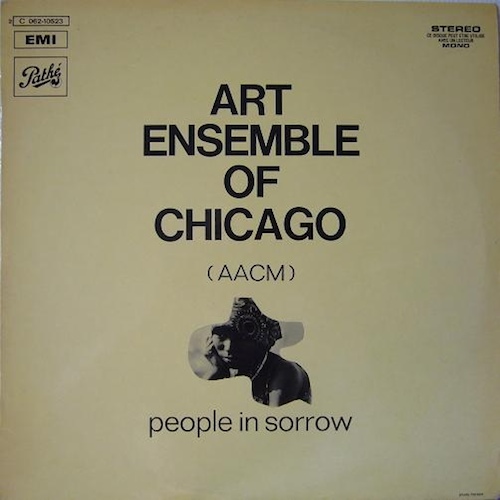

Art Ensemble of Chicago

People In Sorrow

(Pathé, 1969)

Although an album consisting entirely of one largely improvised 40-minute piece might not be appealing to the average listener, this earliest Art Ensemble effort from their Paris days has been loved, studied, and emulated for more than 45 years. It covers the gamut of emotions from fear and anger to love and laughter, with deep silences balanced by keening roars, all intended to reflect the pain and hope of the human condition. In 2013 percussionist Alex Cline reimagined this seminal work in his own release, For People In Sorrow (Cryptogramophone), an homage to the original.

Art Ensemble of Chicago

A Jackson in Your House/Message to Our Folks

(Actuel, 1969 / reissued by Charly, 2001)

This Charly release combines two of the Art Ensembles’s best early discs, recorded at a time when they sought to balance their free-jazz searchings with a formal sense of structure and theatre. Jackson contains moments of good humour, mocking minstrelsy, and Jarman’s deep recitation ‘Ericka’; Message includes a surprisingly effective take on Charlie Parker’s bebop warhorse ‘Dexterity’ and the funky ‘Rock Out’ with Favors on electric bass.

Art Ensemble of Chicago

Live in Paris

(Actuel, 1969)

One of the best documentations of the AEC’s live shows, this bracing set consists of two extended works, each broken into two parts but presented on a single disc as the original double LP offered. ‘Oh, Strange’ segues from straightforward blues to a percussion blowout, then saxophone folk stylings, then free-flowing improv, all making perfect sense to the close listener. ‘Bon Voyage’, the second piece, proudly features vocalist Fontella Bass (Bowie’s wife, of ‘Rescue Me’ fame) as another improvisational instrument, melding beautifully with the ebb and flow of her bandmates.

Art Ensemble of Chicago

Les Stances á Sophie

(Universal, 1970)

Fontella Bass returns on this set of original music initially intended for a French film soundtrack. Never used, it has been well-received as a standalone Art Ensemble recording. ‘Theme de Yoyo’ is profoundly funky and free at the same time, a classic fusion of black music styles. The wide range of dynamics and emotions is perhaps best realized on an unexpected pair of Monteverdi variations, revealing the impressive depth of the musicians’ knowledge.

Art Ensemble of Chicago

Bap-Tizum

(Atlantic, 1972)

One of the AEC’s most accessible recordings for the novice listener, this live session kicks off with a heavy barrage of percussion. Relatively short compositions by Mitchell and Jarman complement a longer Jarman/Favors duet on ‘Unanka’, the extended free-fest ‘Ohnedaruth’, and finally their ostensible theme song, Mitchell’s swinging ‘Odwalla’ (yes, the popular beverage company was named after this tune).

Art Ensemble of Chicago

Fanfare for the Warriors

(Atlantic, 1973)

Another top seller, this disc presents some more concise compositions from the musicians, starting with Favors’ soundscape ‘Illistrum’. Livestock conversations, the majestic title piece, fast Latin fire on ‘What’s To Say’: the full spectrum is again traversed. Mitchell’s ‘Nonaah’, a concert favourite, gets the full-band treatment here; on other occasions it’s a simpler flute feature.

Art Ensemble of Chicago

Nice Guys

(ECM, 1979)

The band took five years away from the studio to tour and restructure their collective vision. Nice Guys was their return to recording and their first effort for the juggernaut ECM label. This time they inject elements of reggae (‘Ja’), drunken swing (the title track) and a Miles Davis homage (‘Dreaming of the Master’) along with the collective improvisations and AACM ferocity.

Art Ensemble of Chicago

The Third Decade

(ECM, 1984)

This album might represent the fullest distillation of all that the Art Ensemble had built upon in twenty-odd years of togetherness. The Caribbean lilt of ‘Zero’, the traditional jazz of ‘Walking in the Moonlight’, some funk here, some meditative musings there, are all clearly realized and melded into a most appealing whole. Even the scant little percussion passages seem more natural and meaningful.

Art Ensemble of Chicago

The Meeting

(Pi Recordings, 2003)

Lester Bowie had shed his mortal coil and habitual white lab coat by the time Jarman returned to the fold. While Bowie’s bleating, witty trumpet is definitely missed on first listen, the band regrouped impressively and continued to explore where they had been and what lay ahead. ‘Hail We Now Sing Joy’ is fully structured and swinging; the fun, choppy funk of Favors’ ‘Tech Ritter and the Megabytes’ is worthy of John Lurie’s Lounge Lizards; and the collective works are perhaps more profound than ever as they reflect upon their lost comrade.

Todd S. Jenkins is the author of Free Jazz and Free Improvisation: An Encyclopedia (Greenwood Press, 2004) and I Know What I Know: The Music of Charles Mingus (Praeger, 2006).