A beginner’s guide to lathe cutting your own records

A lathe cutting 101 for the curious and resourceful.

Words: Caolán Austin & Sarah Minihan (Smalltown America Studio)

Lathe-cutting recordings has been around for a very long time, as long as the format itself. Wanting a solution for short run records for our own bands led us on a journey to buy lathes and to DIY our own runs. At Smalltown America Studio, we were lucky to source a pair of forty-year-old ATOM A-101 machines rescued from a Karaoke bar in Tokyo.

A hunt through eBay will reveal lathes of all shapes and sizes and various project rigs, The Secret Society of Lathe Trolls message board is a great place to start your search. Records are cut by hand and in real-time, so every project we work on is a real labour of love. It has taken us eighteen months to test out the machines’ capabilities and understand optimal cutting conditions. We’ve outlined our discoveries in a handy guide below which we hope serves as a 101 for anyone setting out on the lathe-cutting odyssey.

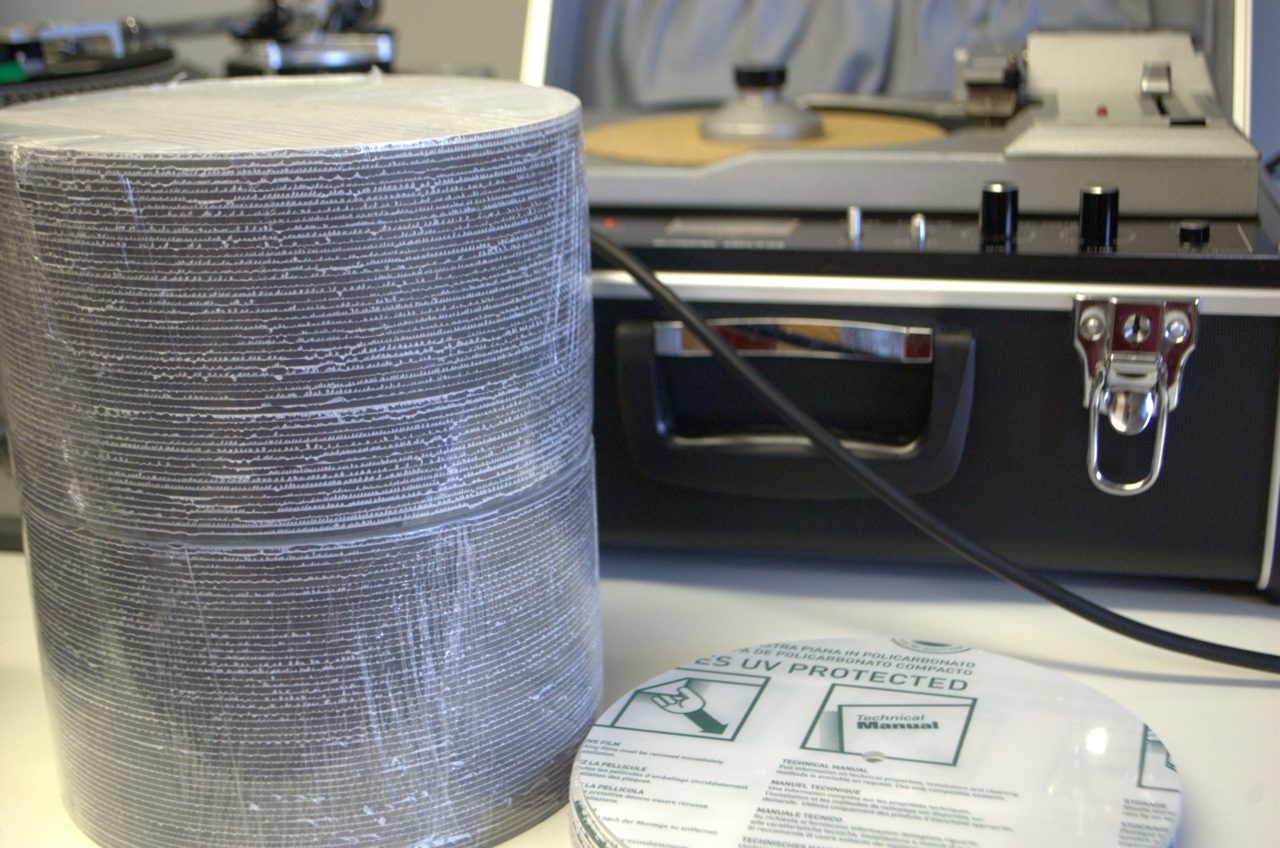

MATERIALS

Discs

Our lathe cuts are etched into transparent polycarbonate discs. We bulk buy polycarbonate sheeting and have the discs routed on a laser CNC machine in Belfast, Northern Ireland. The discs are thicker than standard records, approximately 3mm thick. At this depth the records are more durable and less prone to warping or environmental damage.

Needle

We experimented with a number of different needles: cone shaped, triangle shaped, crystal needles as well as the ever so fancy (and expensive) sapphire cutters. We’ve had the best results from a ‘Presto-Type’ triangle tipped needle that we source from a manufacturer in USA. This particular needle allows us to cut approximately 300 sides before beginning to show effects of degeneration.

Lubricant

Before cutting a record it is important to use a suitable lubricant in order to soften the surface of the polycarbonate disc as well as to prevent friction during the cutting process. After much trial and error we’ve found using lighter fluid or Turtle Wax provides the best type of lubrication. We use ‘Turtle Wax Matt-Finish Cockpit Cleaner’ predominantly because lighter fluid left our engineers non-compos mentis.

To prepare the disc, spray the side you want to cut until it has received even coverage. It’s important to allow time for the turtle wax to soak into the disc (around 2 minutes is ideal). This softens the polycarbonate allowing the needle to easily glide around the surface of the record.

AUDIO PREPARATION

Mastering for Lathe Cutting

We require a .WAV file for mastering the track, usually at a sample rate of 44.1kHz and a bit depth of either 16 or 24 bit. This ensures that we’re working with high quality audio from the beginning. The cutting head on an Atom A-101 is mono-only. We reduce the stereo audio track to mono within our DAW and check to ensure there hasn’t been undue destructive interference.

Occasionally, clients provide us with a mono-mix, which is ideal. Beware of guitars panned hard left and right! We analyse the frequency content of the track. Our cutting head has a frequency range of roughly 60hz to 8kHz and the needle we have chosen has a resonant peak between 1kHz and 2kHz. We acknowledge these attributes when mastering the audio and use a mix of equalisation and light compression to balance these sonic elements.

Machine Preparation

Our machines are fed via our ProTools rig, running through digital-analogue converters that we use for our studio desk. At home, you could use a budget convertor like an M-Box – the important thing to keep in check is the output level to your machine.

Before cutting, make sure that the cutting head is up and check the needle, making sure it’s at the right angle (refer to the picture to see the correct setup). We then take a lead with a ¼ inch TRS connection and connect our audio converter to the lathe. The input level of the audio track into the lathe peaks between -3 and -1 on the VU meter of the lathe. Any more than this will result in wider grooves and distortion on the final cut.

Playback

Playing lathes back is not like playing a regular factory-pressed record, this is mostly because the run-in groove is not deep and it can be difficult to settle the needle on your record player.

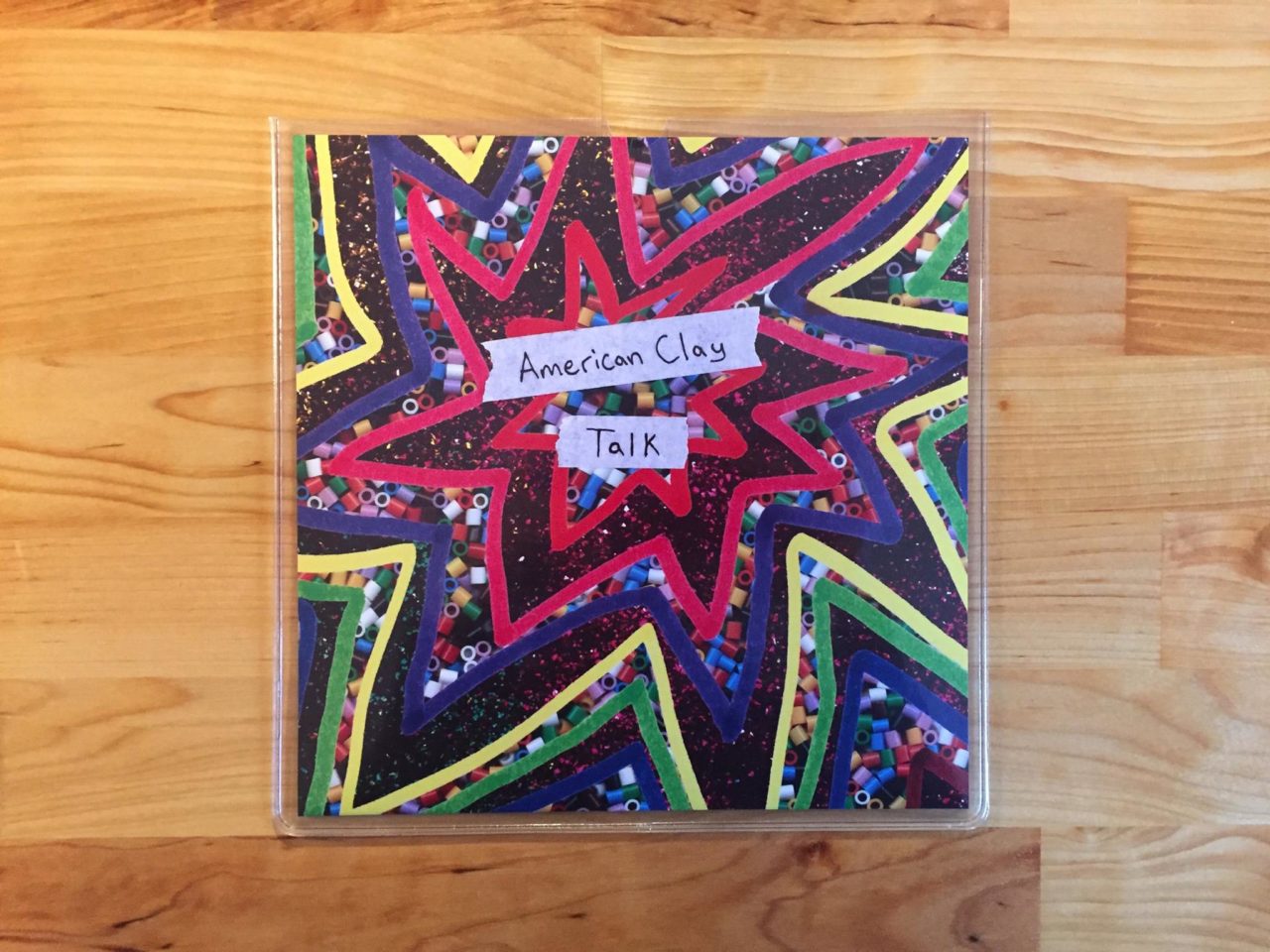

The fun of cutting your own records is immense, the format is esoteric and can be frustrating sometimes, but the payback is such a buzz. Being able to cut music that you’ve just recorded and listen at home on your turntable rather than through your computer means that you commit to a mix and an arrangement much more quickly. For record labels, keen to release more music for bands that can’t command a minimum vinyl run of 500, this is definitely worth a look.

We’ve found that our customers really like the format and love the connection that it gives them to new bands. It’s also a very beautiful format that people are proud to own. If we were to start over again, we’d do things differently and maybe save a year of research – but the experimentation is part of the process and definitely part of the fun. So get your lab coat on and get cutting!

Tips for first timers:

– Clean the record using a micro fiber cloth or static brush before playback.

– Adjust your tone-arm weight to 1.75-2.5grams.

– Adjust anti-skate to suit your own turntable and cartridge.

– Set your playback needle in the run-in groove before rotating the turntable (if possible).

– Lower the tonearm by hand.

– The transparent disc means it can be difficult to see the run-in groove. Be patient – it’s worth it!

– If it sounds distorted it means the needle is not correctly placed in the groove – reset the needle.

– Crank up the volume. Shallow grooves means restricted level of volume and frequency range. Lathe cuts also have a slightly higher noise floor.

Demonstration video featuring Ryan Vail’s single “Invert (Live)” released by Quiet Arch and available to purchase via pledge music. Shot and edited by Colum Coyle.

You can order your own custom short run releases from Smalltown American Studios here.

For more about the art of cutting direct to disc, watch our short film with Crispin Murray and the mobile VF Lathe.