How music came out: 15 records by unsung LGBTQ+ pioneers

Martin Aston tells the underground history of some of music’s most courageous, trail-blazing performers, from 1921 to the present day.

Nashville, Tennessee hasn’t always been virtually all about country music. Between 1964 and 1967, the city’s TV station WLAC Channel 5 broadcast the all-black music series Night Train, concentrating on soul and R&B. On YouTube, there’s one particular clip from 1965 that is dazzling in its vigour and startling in its bravery. This is the mid-sixties, remember. While singing Rufus Thomas’ R&B swinger ‘Walkin’ The Dog’, Jackie Shane carried off bouffant hair, eye-shadow and a sequinned top, shimmering in front of three dapper backing singers, and a horn-blasting band that seemed totally at ease with this gender-fluid vision.

“Prince meets Little Richard meets Eartha Kitt” is how one blog post described Shane. But in 1965, who knows what people made of Shane? At the time, the concept of transgender and transsexuality was barely understood. The first publicised gender reassignment had been in 1952, when former American GI George Jorgensen took the first name of Christine. (Jorgensen even released a single, ‘Crazy Little Men’ in 1957, riding the craze for novelties on 45). But almost everyone who felt they’d been born in the wrong body lived in the closet, under the radar. It wasn’t until 1996 that the state of Tennessee decriminalised (male) homosexuality. By then, Shane had long disappeared, after seven singles and one album, Jackie Shane Live.

I discovered Shane while researching my book on the queer pioneers of popular music, Breaking Down the Walls of Heartache: How Music Came Out, via two documentaries (CBC Radio’s Inside the Music, and Yonge Street: Rock And Roll Stories), and saw, and heard, a revelation: a soul singer with real gravitas and sass.

Discovering a succession of similarly lost and forgotten souls, aligned along the spectrum of what would now be classified as LGBTQ+, was a constant source of joy. Either through their lyrics, persona or performance, they took great risks given the draconian legal and moral restrictions of their time, when there were no, or hardly any, role models before them. In the crate-digging and blogging age, more records are being reissued, such as the first Jackie Shane compilation, Any Other Way, out this week on Numero Uno. In her honour, and in the year of the 50th anniversary of the (partial) legalisation of homosexuality in England and Wales – here are 15 pioneers that helped music come out.

Marek Weber

‘Das Lila Lied’

(Parlophone, 1921)

There had been antecedents, such as British music hall star Fred Barnes, who’d written ‘Black Sheep Of The Family’ in 1907, but that was a more coded admission. Just after WWI, beginning a new era of liberalisation, Germany’s Weimar Republic produced the first gay rights anthem, ‘Das Lila Lied’, aka ‘The Lilac Song’ (lilac – or lavender – became the chosen colour of homosexuality, inspired by the blue rose, thought to combine male and female attributes), written by Mischa Spoliansky and Kurt Schneider (albeit under pseudonyms).

The arrangement is typical of the era’s big-band sound, but the words were anything but typical. The first verse asked why man, who is elsewhere “wise and well,” should outlaw anyone else for being “in lust” with his own kind. The second verse turned angry: “the crime is when love must hide… We will not suffer anymore, but we will be tolerated!” The 1920s turned out to be a particularly tolerant decade, but then came Adolf Hitler.

Gene Malin

‘I’d Rather Be Spanish Than Mannish’

(Columbia, 1934)

1920s Harlem was equally tolerant and cultural. Its most legendary voices, Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey, sung freely about their bisexuality, but far less documented are the male blues equivalents like George Hannah, who sang ‘Freakish Man Blues’, or the scene that sprouted in New York at the end of the decade. In 1930, the Pansy Club opened in Times Square, with ‘Mistress of Ceremonies’ Karyl Norman, the first known female impersonator to write his own songs. Sadly, no recordings exist, just sheet music with song-titles such as ‘Nobody Lied (When They Said that I Cried Over You)’.

But Gene ‘Jean’ Malin, who performed in male attire, did make a record – albeit posthumously – after he accidentally reversed his car off a pier. ‘I’d Rather be Spanish than Mannish’ is possibly the campest piece of vinyl – or shellac – ever, with lines like, “there’s something about bulls I like…” But why Spanish? Probably the rhyme with ‘mannish’ was too good to pass up. But it also inferred that America didn’t cultivate pansies – everyone’s queer in Europe, aren’t they?

Spivy

Seven Gay Sophisticated Songs

(Commodore, 1939)

America’s Great Depression triggered a massive economic downturn, and with Hitler’s Germany turning up the heat, a conservative and religious backlash saw all advances for gay and lesbians recede to 19th century conditions. The occasional suggestive parody slipped out, but only sung by men, until Bertha Levine (or LeVoe), aka Spivy. “Gay, exciting, triple-entendre sophistication,” one reviewer described the owner of New York nightclub Spivy’s Roof (where a promising young pianist, Władziu Valentino Liberace, got an early break).

Spivy was a performer in her own right, though going by Seven Gay Sophisticated Songs, she spoke her songs over piano rather than sang. The lyrics operated the same policy as her club, an air of discretion: the only way to stay in business. Take ‘Alley Cat’, whose proud attribute is surgically removed: ‘No longer will I take chances with the maids / Now I pass them by / And hear them cry / There goes that pansy cat.’

Frances Faye

Caught In The Act

(GNP, 1959)

In the 1940s, American blues got tougher: more guitar, more swagger, and performers like Sister Rosetta Tharpe and Big Mama Thornton, who were major influences on Little Richard and Elvis Presley. But neither sang about bisexuality. That topic remained the preserve of nightclub entertainers, like Frances Faye, who was twice-married but happy to mention her girlfriend/manager Teri Shepherd’s name in a cover of the Gershwins’ ‘The Man I Love’, and recast Cole Porter’s classic ‘Night and Day’ as a terrific Latino rumble with the rap: ‘Night and say/ Olé! Olé / What is there to say? / Frances Faye/Gay, gay, gay, gay/Is there another way?’.

‘Frances and her Friends’ also reprised the facts of life over a terrific swing metre: ‘I know a guy named Joey, Joey goes with Moey / Moey goes with Hymie and Hymie goes with Sadie/ And Sadie goes with Abie…” She didn’t record either until her 1959 live album, but it’s evidence that the feisty female archetype, from Eartha Kitt to Bette Midler, started here.

Jackie Shane

‘Any Other Way’

(Sue Records Inc., 1962)

Shane’s new compilation, Any Other Way, is named after her only hit, which reached number two on Toronto’s CHUM Chart, following her move to Canada after a decade-plus of homophobia and hassle. Her cover of William Bell’s song is a soul slow-burner, with a subtle twist given who was now singing it. In Bell’s original, a woman sends a friend to check on the man she’s dumped, who responds, pride before the truth: “Tell her that I’m happy/Tell her that I’m gay/Tell her that I wouldn’t have it any other way.” Shane, of course, knew the ‘underground’ meaning of ‘gay’, which was still not common parlance at the time, turning the song into a statement of defiance. She’s happy her way, and wouldn’t have it any other way.

Various Artists

Queen Is In The Closet

(Camp Records, 1964)

Also in 1962, an album appeared in choice record store racks, named Love is a Drag – For Adult Listeners Only, Sultry Stylings by a Most Unusual Vocalist, in which songs written for women to sing to men were sung by a man (jazz crooner Gene Howard). In the wake of the politicised gay (the Mattachine Society) and lesbian (Daughters of Bilitis) organisations formed in the 1950s came the concept of a gay community, which could be targeted at consumers, and entertainment-based magazines.

In 1964, Camp Records placed an ad in One magazine for new album Queen Is In The Closet, with the tagline, ‘It’s terrific! It’s mad! It’s gay!” The compilation parodied gay stereotypes (‘Stanley The Manly Transvestite’, ‘Lil’ Liza Mike’ etc) and musical styles (doo-wop, Broadway, cabaret, pop, Latin) across the likes of ‘Weekend Of A Hairdresser’ and ‘Rough Trade’. A string of singles was released under fictitious artist names, such as ‘Homer the Happy Little Homo’, credited to Byrd E. Bath & The Gentle-Men. No one knows if the intent was to laugh at, or with, homosexuals, as still no one knows who was behind Camp, let alone their motives.

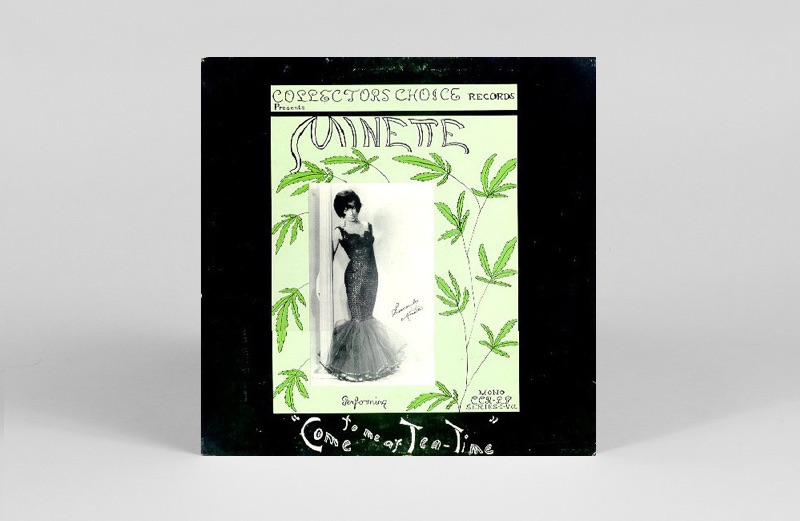

Minette

Come To Me At Tea Time

(Collector’s Choice, 1968)

Jacques Minette began doing drag in the late 1940s, but her performance was as a chanteuse rather than the usual movie star, and she wrote her own parodies, such as remodelling ‘The Lady In Red’ as ‘The Lezzie In Red’ (while acting in experimental 8mm films directed by cult photographer Avery Willard.) She later confessed that LSD changed her life, and helped create an album, the first by a drag queen that didn’t depend on comedy, parody or innuendo.

Her louche drawl bore hallmarks of cabaret, while her rickety backing band sounded like they were playing at the end of a very long night. There was a clear psychedelic mood too, and lyrics such as those on ‘Minette’s 69th Trip’ and ‘On a Psychedelic Astro-Flight’, but Minette was serious too, as heard on the Vietnam War-inspired ‘Hey, Hey, LBJ, How Many Kids Did You Kill Today?’

Maxine Feldman

‘Angry Atthis’

(Harrison & Tyler Productions, 1971)

In 1960, Edith Eyde, trading as Lisa Ben (get it?), released a queer parody of the traditional song ‘Frankie And Johnny,’ on the DOB (Daughters Of Bilitis) label. But another 11 years passed before two more boldly politicised singles appeared, two years after the Stonewall riots triggered the Gay Liberation movement. In 1971, Madeline Davis released the folky ‘Stonewall Nation’ after attending the US’s first nationwide gay rights march in New York state capital Albany. And that same year, Maxine Feldman released a more vociferous manifesto.

‘Angry Atthis’ was named after the lover of the Greek poet Sappho, and a pun on ‘angry at this’, inspired by the constant police harassment she’d experienced in lesbian bars, which made her feel “useless and sick. I felt we were worth a lot more.” Her performance was pure anguish and verve: “Feel like we’re animals in cages/And have you seen the lights in the gay bar/Not revealing wrinkles or rages/God forbid we reveal who we are…” ending with the raging, “No longer afraid of being a . . . les-BIAN!’” “Women’s music,” as the overtly lesbian-based music movement was christened, began here.

Michael Cohen

What Did You Expect? Songs About the Experiences of Being Gay

(Folkways, 1973)

In 1972, David Bowie/Ziggy Stardust’s meteoric rise validated gay culture like no artist before, musical or otherwise. But he refused to get political, and in any case, he was hardly committed to the bisexual cause. (He appeared to only sleep with men who could further his career ambitions; post-fame, he was only ever associated with women). Likewise, Lou Reed. For franker statements of intent, you had to wait a year, when Alix Dobkin self-released the first lesbian-driven album, View From Gay Head, while Lavender Country’s self-titled debut album was country music’s first gay statement.

Their record was reissued in 2014, so instead I’m spotlighting Michael Cohen, whose extended bout of aversion therapy had led to drugs, and this classic singer-songwriter confessional, beautifully stark and solemn, much like his namesake Leonard. The pain and shame of the pre-Stonewall years is all here. Take ‘Orion’, which tackled sex in a way that no songwriting peer was willing: “I’ve been digging up the ruins from all my high school years / The gym locker fantasies and the mad masturbatory fears.”

Smokey

‘Leather’

(S&M records, 1974)

For real queer glam rock, you either need Starbuck’s single ‘Do You Like Boys’ and Wicked Lady’s ‘Girls Love Girls’ (both only released in the Netherlands), access to Handbag’s unreleased album (by the time they released a record, it was 1978 and they’d mutated to ‘new wave’ and abandoned the sexualised lyrics), or LA duo Smokey.

Vocalist John ‘Smokey’ Cordon and studio bod EJ Emmon didn’t hold back. Their debut single was called ‘Leather’, but they found the record industry didn’t want to know. Cordon recalls one executive saying, “We can’t put this out, it’s a fucking gay record, what’s the matter with you? It’s really good though,” despite being the de facto house band at Rodney Bingenheimer’s English Disco nightclub in LA. So, they formed their own label, S&M, with a logo of a muscled arm wearing a leather cuff with the hand curled up into a fist. Compromise was not an option. “People said, ‘Sing a ballad, do this and that’,” Cordon recalled. “But, fuck you, we’re not going to sell out.”

Elton Motello

‘Jet Boy Jet Girl’

(Lightning Records, 1978)

You would have thought punk rock’s revolutionary mores would have pushed vehemently for gay rights. Yet besides Tom Robinson – whose hit ‘(Sing If You’re) Glad To Be Gay’ was more music hall than punk – there was precious little proof. Buzzcocks frontman Pete Shelley talked about bisexuality and wore badges (like ‘I like boys’ and ‘How dare you presume I’m heterosexual?’) but his songs were purposely gender-neutral.

Among the very occasional bold excursion, like 999’s charged ‘The Boy Can’t Make It With Girls’, and Drug Addix’s Lou Reed parody ‘Gay Boys In Bondage’, the best was Elton Motello’s stamping ‘Jet Boy Jet Girl’, sung from the standpoint of a teenager rejected by his older boyfriend. Only problem was, six years after Lou Reed’s ‘Walk On The Wild Side’, the BBC had cottoned on to the meaning of ‘giving head,’ and banned Motello’s record. To add insult to injury, a few months later, the same backing track was given new lyrics and title. ‘Ca Plane Pour Moi’ was a Top 10 hit across Europe for Plastic Bertrand, a pseudonym for Motello’s drummer Roger Jouret.

Rough Trade

‘High School Confidential’

(Boardwalk Entertainment Company, 1980)

Born in Northern England but raised in Canada, Carole Pope had taken stock of Janis Joplin (whose lovers were mostly women) and Jackie Shane: “I’d heard ‘Any Other Way,’ and couldn’t believe people didn’t know what she was singing,” Pope recalled. She experienced a similar reaction with ‘High School Confidential,’ a Top 20 Canadian single in 1981 for Rough Trade, her alliance with multi-instrumentalist Kevan Staples.

“I was influenced by gay men and their image, the leather and fetish wear,” Pope said. “I mean, where were the lesbians? It took a lot longer to find them.” After appearing on the soundtrack of William Friedkin’s Cruising, they released ‘High School Confidential,’ a taut, prowling, sultry classic, and pretty explicit: “She’s a cool, blonde, scheming bitch / She makes my body twitch… It makes me cream my jeans when she comes my way.” “Cream my jeans, you can’t say that, it’s too risqué!” Pope was told. “And I was the one that invented the crotch-grab, before Michael Jackson and Madonna!”

Age Of Consent

‘Fight Back’

(single, 1981)

Hip-hop went mainstream with virtually its first release, and homophobic too, from the Sugarhill Gang’s 1979 single ‘Rapper’s Delight’ (about Superman: “He’s a fairy, I do suppose / Flyin’ through the air in pantyhose”), and Grandmaster Flash’s ‘The Message’ (references to fag-hags and “an undercover fag”).

For two white gay men (John Callahan and David Hughes) to write a gay rap was either brave, or foolhardy. Under the name Age Of Consent (after Bronski Beat’s 1984 single ‘Small Town Boy’), they released ‘Fight Back’, beginning by emulating rap’s origins in machismo – “I am the knight of the might / When evenin’ comes I spread delight”– before branching out to tackle gay culture: “Well, I’ve had it with Levi’s, disco, lifting weights / Alligator shirts and going on dates / The size of this, the size of that/ No blacks, no freaks, no fems, no fats.” They split in 1983 before releasing an album, though Old School On The Down Low was released in 2004.

The Radiators

‘Under Clery’s Clock’

(Chiswick, 1987)

Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s zillion-selling ‘Relax’ must still be the biggest selling record with a same-sex tag, but for me, Bronski Beat’s ‘Smalltown Boy’ is equally anthemic for those times, a heartfelt and vulnerable ballad (as opposed to Frankie’s hedonistic celebration). It epitomised the pain/shame of growing up gay, and carried the bold message of the promo video, which showed real-life cruising, gay-bashing and a happy escape to the bit city with gay mates in tow. “There had been gay singers before but not this kind of evocative, emotional plea. We didn’t drown the song in ambiguity; we didn’t disguise it or who Bronski Beat were.”

But ‘Smalltown Boy’ was a number 3 UK hit, and few know of Ireland’s emotional equivalent, the first song from that country with an openly gay subject, written by Philip Chevron, former frontman of the Radiators From Space, one of Ireland’s most beloved punk bands. Post-1981 split, he moved to London, and joined The Pogues, but when the Radiators reformed in 1987 for an AIDS benefit, Chevron composed ‘Under Clery’s Clock,’ an exquisitely haunting lament about two teenage boys who arrange a rendezvous under the Dublin landmark of the title: “Long, lonely nights just imagining his face / Only in dreams do I kiss him and embrace / Cold morning light, he’s gone with only shame to take his place.”

Various Artists

Rainbow Riots

(Musikverket, 2017)

In 1979, Wicked Lady sang, “Girls love girls, boys love boys / It doesn’t matter.” But evidently it does, especially in some parts of the world, such as Africa, the Middle East and Eastern Europe. Most recently, a concert in Egypt by Mashrou’ Leila, fronted by openly gay Lebanese singer Hanned Sinno, was a scene of celebration, with rainbow flags hosted aloft. Afterwards, seven men were arrested for the flag-waving (and even for approving of the flag-waving on Facebook), for the apparent crime of “promoting sexual deviancy,” even though homosexuality is not illegal. They apparently remain in prison.

In countries such as Uganda, it’s far worse. There, homosexuality is illegal, and draconian sentences (14 years, say) are the norm. In opposition, Swedish dance musician and producer Petter Wallenberg is fronting Rainbow Riots, originally a forum/network to counteract the ‘hate music’ of Jamaican dancehall/ragga and now, “the world’s first record label for LGBTQ artists from countries where their human rights are abused.” It stars a queer rapper from Malawi, a trans Zulu singer, dancehall reformer Mista Majah P (a Jamaican living in California) and LGBTQ+ artists from Uganda. “This is the story of the battle between hate and prejudice versus love and freedom,” says Wallenberg. “Above all, Rainbow Riots is a story of creativity triumphing over adversity. This story is only just beginning.”

Illustration by Vickie Amiralis.