Published on

June 21, 2018

Category

Features

It’s a London thing.

There’s an unspoken mantra in virtually every creative industry that to get ahead you need to be better than everyone else, at the expense of those around you. In London, something refreshingly different is happening, taking root in an unlikely locale south of the river: Hither Green.

From the outside, the building resembles an unassuming corner block, the kind you’d walk by every day for years without noticing. Step inside though, and you’ll find a hub of artist spaces, walls adorned with glow-in-the-dark logos, graffiti characters that stand two storeys tall, glinting drum kits peeking out of half open doorways.

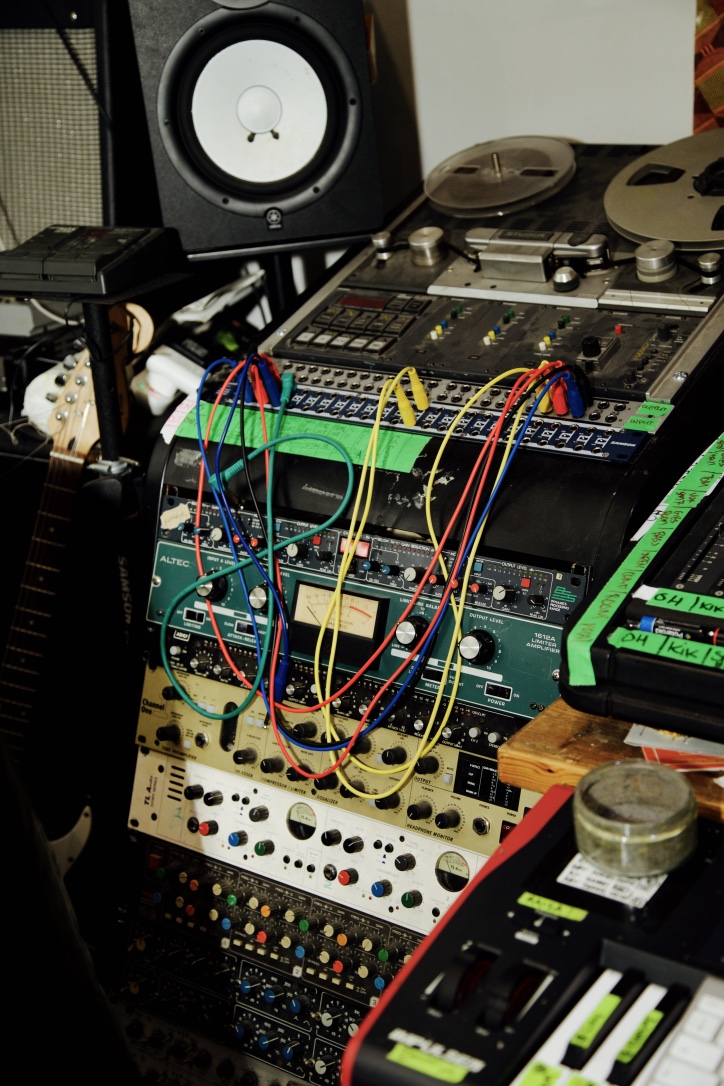

At the heart of this is Done London – a print studio/clothing design company, and drummer/producer Kwake Bass’ music studio. Together Done’s Tom Andrews and Will Conwy, Kwake Bass, and manager Ed Feilden are DEM1NS – a collaborative endeavour where every release is a multi-faceted combination of music, clothing and prints. But this isn’t ‘just’ a wavy streetwear company with releases or a record label with heavy garms.

This is a crew built around the idea that if you empower those around you to do better, everyone does better. Support others when you’re in a position to do so. Be nice. Manners are free. It’s also a collective where the divide between music, graphic design, clothing, art and print doesn’t really exist, because why should it? The ethos is not rocket science, but it’s a stark change from days of yore, one that’s spreading across the city and beyond, spearheaded by the scene that those involved with DEM1NS are at the helm of.

It reaches well outside of the studio in South London, where Kwake Bass shares a space with Wu-Lu, and Done’s print HQ houses a signwriter, to like-minded pals including Kate Tempest, Tirzah, Shabaka Hutchings, Ryan Hawaii, and Sampha to name only a few.

Though DEM1NS isn’t even a year old, them ones go way back…

Let’s start at the beginning with you Kwake Bass, did you have a musical upbringing?

Kwake Bass: Both of my parents have come from music. Dad was a session bass player back in the day, and he had a band called Person’s Unknown. I mean, I’m biased, but it was very ahead of its time. It’s kinda like ‘dub punk’ to put it into layman’s terms. He did sessions for Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry back in the day. Dillinger, remember Dillinger? “I got cocaaaaaaaaine.” He toured that for fucking years.

Mum was out working for a women’s equality unit, and did a lot for the community, while my dad would be at home looking after me and working in the studio. I’d just be strapped in, happy as Larry all day.

Ed Feilden: Your Mum is formidable. She is amazing.

She sounds like an absolute hero.

KB: Proper, proper hardcore. Back then – I call it the women’s equality scene – those are the kind of parties my mum was DJing, that was her ting. My Mum is an avid, hardcore feminist – well not a feminist, she’d get pissed off if I called her a feminist – she’s like, “this ain’t feminism, this is fucking reality – ya get me, deal with the truth man!”

You couldn’t have men in these environments. So she’d be like: “well, my son’s allowed in here. I’ve got no way of supporting him while I DJ, I’ve got no child care, you want me to DJ at silly o’clock in the morning? Yeah alright, there aren’t men in here, but my boy is going to be here.” So I’d be in there half asleep, I’d say between five and ten years old.

I have loads of memories of always saying to her, “Mum, why are your mates at a party, arguing?” And she’d say: “they’re not arguing they’re talking about things that are going on.” They were obviously getting riled up about social situations, you get what I’m saying? But me as a young boy, I’m thinking: these two people are having a fucking row of terror! They’re shouting at each other! She’d say, “they’re not angry at each other, they’re just working it out.”

There’s a strong sense of rebellion, is it against a social construct or is it something else?

KB: The way things are. The way things are is the way I’ll put it, if we’re gonna be brief. But I’ve always questioned and I’ve always had a way of looking at things a bit differently.

I think that’s why me and Kate Tempest connected at such a young age. Neither of us can remember the first time we met each other. We just remember being bezzies. Literally. One day I didn’t know her, and the next we were in each others’ houses every day for years. A lot of that was us sitting down and saying, “right we gotta make music and tell people what’s going on and get people to think differently because of this fuckery.” Ya get what I’m saying? That all comes again from my parents being on that side of the creative fence where the cause is just as heavy as the song. All of that shit, I think that’s a big part of my musical upbringing.

E: But I think that also feeds into what the ethos is with DEM1NS.

KB: That’s why I mention it!

Will Conwy: What’s good about that is it was a natural thing. Gilles also approached us to do it partly because we were friends. We became friends because we were next to each other in the studio together, and we had all these connections. But it also ties into our similar ways of working – you’re just doing it for yourself, there’s no corporate shit involved. It suited him musically because that’s what he’s been doing for years.

Tom Andrews: All of those little subcultures, like graffiti and certain types of electronic music, hip-hop, BMXing, skateboarding, they all merge together. If you can find people who are really into what you’re into, you kind of gravitate towards each other.

W: A lot of our work has come from graffiti culture. That definitely positioned us as a print studio that would work in that sort of culture. So if someone who was a graf writer wanted to get a t-shirt printed, they would then come to us and be like, “can you print these for me?” because they know that we’ve done stuff with their friends. I think that is definitely part of it.

How did you do this before you had the Hither Green studio?

W: Tom had his studio in Hackney Wick, so I used to go after work and print t-shirts there. It was missions in those days, because I lived in Clapham. But I didn’t really care, because I wanted to do it, so it didn’t seem long to me at the time. It felt like I had a place I could go and print, when Tom and these lot were just hooking it up.

T: Before all those studios got properly fixed in and sealed up we used to have to bag up all of our stuff and take it up onto the mezzanines that were built. Cover it all with tarpaulin, and sit there for the entire night while the rave happened, so no one came up there and stole shit and fucked shit up. We got to party, kind of. It was fun.

W: I mean it was that sort of thing where, I’d go there to print shirts, and you’d be on it… But there would always be other people just getting fucked, and I’d think, “ugh this is mad distracting.” It was also fun so…

T: It was so lucky that this place in Hither Green happened to be available. It was unheard of for people to move down here who aren’t from this part of town already though.

So when did you start Done?

W: In the beginning it was more about the designs than it was the name. Done, just the brand name, came about because I needed a name for the things I was doing. I spent ages thinking about it, then I was talking to a mate, “saying I need to get it done”, and he was like… “just call it ‘Done'” Finished. Sorted.

The first design that I came up with that was tube-related was the Southbound one. And people just wanted it. At first I sold them for like £5 each. I’d take them to festivals and swap them, that was my currency. That kind of led on to thinking: people really like the underground imagery, they really connect to it, it’s ‘my local’, and the graphics work nicely on the t-shirt as well.

T: In the beginning, we started with a lot of underground graphics re-appropriated. Then we got told off for that.

Really? Who got in contact about it?

T: Yeeeeeeah. It was almost exactly the five year anniversary of Done. We were at a festival in Croatia, and Will got an email through from TFL, because our names were splashed all over this video that had just gone up on YouTube about us.

W: In the letter you can see the screenshot that’s like ‘See figure 1’ or whatever, referencing the point they’re making, and I could see all the tabs they’d screenshotted… the Facebook page with my name, my email, my website, all the links about me. And I was like: sheeeeeeeeeeeeeyat. Sheeeeeyat Sheeeyat Sheeeeyat.

They said we can apply for a copyright, there’s a fee per design, and then they may or may not approve it. If they do approve it they take 10% of all profits, or something like that. It just couldn’t add up, for the amount of t-shirts that we actually had left to sell, it wasn’t worth it at all. In a way, it was quite good though, because it meant the people who did get the shirts got gassed that they had one in the first place.

What happened after those initial runs of t-shirts?

W: We have done a lot of printing for other companies, that’s how we kind of survived. I think it’s only in the last year we’ve decided to try and be like ‘fuck it’ and do more of our own shit. It’s always been a balance between the two. A lot of it is a mate of a mate, it’s all word of mouth.

Kurupt FM, we did their first ever tee, or one of the first. They were cool, we met them through The Lurkers who are basically old mates we know through the graffiti scene. They know the guys from PJDN. I saw Grindah at a festival wearing a Lurkers t-shirt, and I said, “alright yeah you know those guys?” He said, “mate we need t-shirts, print them, these are banging we want them the same as these.”

We did 200 and they came back saying, “they’re sold out we need like 500? We need 1000? we need 2000? What you saying price-wise? Can you start like sending them out for us?” and I was like “Aaaaaaaaaaaaah.”

How important has the studio space here in Hither Green been for DEM1NS development?

W: I don’t think (DEM1NS) necessarily would have happened unless we were here next to each other, because Gilles wouldn’t have reached out for somewhere so readily like “let’s go do a merch thing.” It came together in a more natural way.

Initially we said, “we’ll just do a t-shirt together”, but Gilles has got endless creative ideas, so we thought “we can do more” and keep it going from our side. What’s been great is it’s brought together both of our networks, that were already separate entities in themselves, but overlapped loads.

T: It takes me to the moment when we were taking all of the merch down to the shops, and Gilles just unleashed.

KB: Tell them Tom!

T: I don’t even know if Gilles fully realised the whole concept of what DEM1NS encompasses until he was in the back of the van that day. But it was so deep and so vast. I remember texting him the next day, because it took the whole evening to sink in, messaging him saying “I get it now… I get what this is about, it’s not just about making t-shirts, it’s about spreading a whole concept to a whole audience that congregates around you because they’re interested in the sound you’re making, in the images you’re producing, in the clothes that you’re making. But beyond that there’s actually a deep underlying message to say: think about what you’re doing, think about what you’re getting involved with, think about the way you’re talking to people, the language you’re using, the music you’re using to broadcast that, the clothes you’re wearing to represent who you are. Come together and actually think about what you’re doing. Come outside of your box, observe society and make a fucking difference.”

I was going to ask what the “idea” behind DEM1NS is, which you’ve already started to answer?

KB: That conversation that day, I learned a lot, I’m still going through it, litmus testing ideas and all of that. But at that point I myself was like, this is going to work! This is going to work! This is happening and it’s going to work.

The identity on the wall, this is me: Sun Ra, Ackamoor. Posters become representations of identity. Fast forward, the t-shirt is the new poster.

What I’m trying to do is to document these terms that are social commentary. The t-shirt is the cultural commentary, but it’s a different type of commentary because we’re documenting these terms at a specific time. So when they look back they have some BBC music documentary about the London jazz scene, they’ll see Shabaka Hutchings wearing the DEM1NS jumper in New York, they’ll see Joe [Armon-Jones] at the New York Jazz Festival with some write up from Rolling Stone or some shit.

That London jazz article with Nubya [Garcia] on the cover is insane. People try and frame it: “OK WHAT IS THIS? It’s exciting, what’s going on?” Like with the ‘jazz’ scene – maybe it’s not necessarily jazz, but you have to call it something.

KB: My brain is purely creative, and I’m in my lane now. Ya get me. Doing my bit. And Eddie does his bit in understanding where we’re going, and not just filtering – we make a joke that you’ve got to filter my ideas into reality – it’s not just the filtering.

T: He’s the skipper!

KB: It’s like the expectation management of what’s available, what’s realistic, and being able to actually steer it, so we can have a platform and a voice without being cheesy or contrived or caught-up.

That bit before you put the paint on the page when you’re going ‘hmmmmmsasgrrmmmhh’ That’s when the mind is the most ‘whirrrrrrrrr’.

How important is it that the creativity has some kind of structure, or is associated with a coherent brand?

W: Well, we do need some level of organisation. And, because of the fact that the internet is so accessible now, kids as young as 12 are on their own brand. For our personal brand, we need to present ourselves well, and you need to have good creative content in order to capture the audience, and to deliver the message that you want. It still has to be properly considered.

T: To add to this, language constructs our understanding of everything. Without language, without words, we wouldn’t have an idea of how to describe a feeling, a culture. These words that Gilles coming up with are the way that people understand each other. And, the way a group of people in this community in London understand each other is now spreading to other towns, other countries – we use these words to understand and communicate.

E: You just touched on the full spectrum.

KB: These ain’t my terms. I am documenting, I’m on some Attenborough shit. A lot of different people ask: “how’d you get all them people on stage, how did you know this geezer and that geezer, how were you able to talk to one man one way and talk to another man in another way?” That’s down to me, as a person. I understand that.

KB: But it’s also about me as a creative, on that vessel shit. I’d like to be able to document it in a way that I can put music to it. That’s interesting to me, and then get my bredren who takes pictures to make something while my bredren’s playing music. I don’t know what they’re going to play, even they don’t know what they’re going to play. But I’m going to watch and see what happens innit, and the result of that is the ting I want to hear and listen and look at. That’s funky to me, do you see what I’m saying?

E: We’re a community of the creative class, living in a time of austerity, when the government is breaking down these types of communities. We feel empowered to be able to present alternatives for kids coming up. The whole clothing aspect for me was just a vision: that consumerism is the biggest religion in the country, but once you have people subscribe to your church then you can present your message.

Is there a community driven element to DEM1NS already?

E: As it grows in 10, 15 years we’ll be embedded in social projects as well. But… to get peoples’ attention you’ve got to be on Instagram essentially. There’s a method behind the madness, and it’s not a superficial one.

T: When we talked about we want to do with DEM1NS, what we’re doing is educating people by creating something more than ‘just’ a piece of music and a clothing brand. It’s almost trying to educate people and show them that being independent to one’s own life and doing what one wants to do to make oneself happy is a really important part of achieving what everyone tries to achieve in life, which is happiness.

E: What’s important, to be specific about the clothes at this stage in the next year, or whatever is in front of us, is that there will be a bunch of phrases that are essentially going to be associated with DEM1NS. But at the core what all the phrases translate to is ‘do you understand me?’ It’s a case of demonstrating and understanding. Understanding one another, through whatever way that person relates to – the music, the t-shirts, the artwork – is literally at the core of this whole thing.

W: And that aesthetic that we’ve built behind it, in a way that’s just an amalgamation of your creative self and us. So we’re the example of ‘we’re just doing our thing’ and it’s trying to empower and send the message to other people that they can do their shit as well.

But also going back to the ethos behind what we are: It ties back to how our studio worked in the beginnings, and still does today. We collaborate with a lot of friends where we say, “you haven’t got that much money we’ll help you out with the artwork, we’ll get the t-shirts printed, fuck it we’ll even do it on tick for you. And then you can sell the shirts and come back to us,” and sort of help people get on their way.

Gilles has worked with so many musicians in a similar way where it’s like: come into the place here. There are people rehearsing all the time when the space is free, just allowing the access, and sharing what we’ve got with other people around us who are good creatives. Because we’re blessed to have this space now between us. We know that in a way, and I think that’s what DEM1NS is about as well.

T: It’s a ‘for the people, by the people’ kind of thing.

Head to DEM1NS for more.

Cover and DEM1NS Wu-Lu photos by Will Conwy. DEM1NS YoYo and Muti photos by Jessica Eliza Ross. Additional Photos by Elina Abidin.