Published on

July 19, 2018

Category

Features

A guide to the sound of the mythical analogue synthesizer, from the late ’60s to the modern day.

A certain mystique surrounds the EMS Synthi 100. Approximately thirty of these complex systems were made, but of that modest number, most were (and still are) owned by renowned musicians and recording studios. Among the diverse class of creative minds who set about taming this groundbreaking synth were the teams at Radio Beograda and the BBC Radiophonic workshop, the jazz pianist Wolfgang Dauner and the Swiss producer Bruno Spoerri.

The Synthi 100 was EMS’ second major project after the VCS3 monophonic synth, and was unusual in that it was created according to the budget and requirements of Radio Beograda, who commissioned it for their Elektronski Studio. Peter Zinovieff, one of three remarkable minds behind EMS, worked with Belgrade-based composer Paul Pignon and a small team of designers to refine the initial design, while the BBC Radiophonic Workshop also provided input on the final specs.

Zinovieff was one of only a few British composers and innovators championing electronic music as an artform, and developing technologies for its means during the mid-sixties. His early inventions with Tristram Cary and David Cockerell were guided by what he — as a musician and engineer — wished had been available on the music market.

Although the idea didn’t exist at the time, the Synthi 100 was, in some ways, a prototypical digital audio workstation: a system that enabled the user to generate, sculpt, sequence and playback electronic sound. Malcolm Clarke of the BBC Radiophonic workshop demonstrated those capabilities in a fascinating 1979 documentary. As Frances Morgan wrote for Fylkingen, “the marketing of the Synthi 100 portrayed it not so much as an instrument but as a studio in itself: an entire working environment.”

Using the Synthi 100 wasn’t something you could simply ‘pick up’. The Harry Roche Constellation used one for less than twenty seconds on their 1973 record Spiral, but still required EMS sales demonstrators John Holbrook and Robin Wood to program it. As such, its users were somewhat self-selective, and only those with an inquisitive nature, or willingness to grapple with the technology, were able to utilise the machine. Here are ten records that showcase its boundless sound palette, and the music it has helped to realise.

Curved Air

Phantasmagoria

(Warner Bros. records, 1972)

A Synthi 100 was installed at EMS’ own London studio from the outset. Having used the VCS3 on Second Album, Curved Air keyboardist Francis Monkman was clearly itching to work with the next piece of EMS technology. He recorded two tracks for Phantasmagoria with the EMS team who would’ve helped to ensure he got the best out of it. On ‘Ultra-Vivaldi’, an interlude which concludes the first side of the record, we hear a Synthi-generated bassline, keyboard melody and modulated string synth line playing in unison. Monkman accelerates the ‘clockrate’ (a kind of master tempo dial) towards the end of the track, taking the sequenced parts up to a superhuman speed. On ‘Whose Shoulder Are You Looking Over Anyway?’, he uses the Synthi 100 alongside a PDP-8 computer to process spoken word and program dissonant tones. The bold tracks are completely at odds with the rest of the record, and could not have come into being without the synthesizer and computer combo.

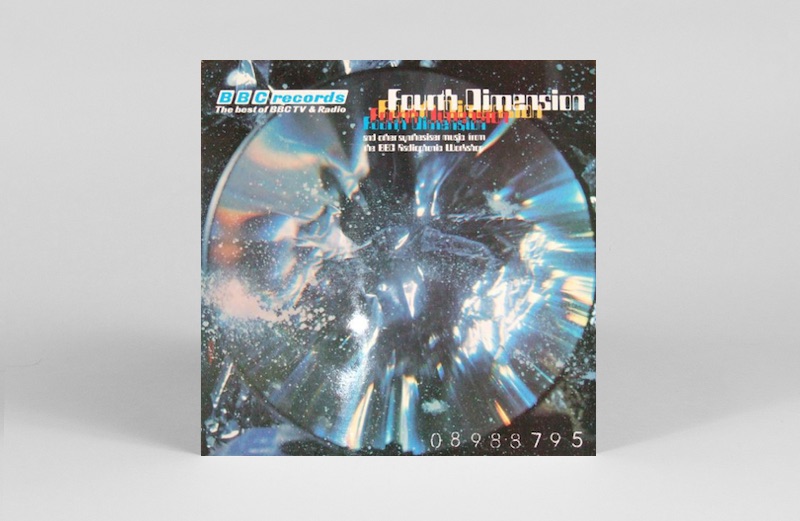

BBC Radiophonic Workshop

Fourth Dimension

(BBC records, 1973)

The BBC Radiophonic Workshop was the second institution to order a Synthi 100, and Fourth Dimension was the first commercially released Radiophonic LP following its installation at Maida Vale. The synth had already stamped its mark on the Radiophonic’s soundtrack and foley effects work, and Paddy Kingsland was one of the chief composers using it for theme tune work too. Many of the tracks on Fourth Dimension are light and spirited theme tunes – upon which the VCS3 and Synthi 100 stick out like a sore thumb. But, as Kingsland reminded VF in 2014, the workshop composers worked to briefs and strict deadlines, servicing the programmes with songs and accompanied sound design. Despite that, they were able to create some of the most innovative synthesized textures and music set to record in that era.

Radovanović, Pignon, Devčić, Kalčič

Elektronski Studio Radio Beograda

(PGP RTB, 1975)

They may have been heavily involved in the design of the Synthi 100, but Radio Beograda’s ‘third program’ took delivery of model number 4 rather than number 1. Installed in 1971, those working at the station took their time acquainting themselves with the new apparatus, developing a manual for the Synthi 100 and incorporating it into the studio workflow. By 1972, Paul Pignon completed his ‘Hardware Performance’ composition using the Synthi 100, before Vladan Radovanović made a similarly avant-garde composition called ‘Electra’ in 1974. Both pieces exceed ten minutes, and showcased the tonal variation that the synth could achieve. Presets couldn’t be programmed, but the composer could position matrix pins (resistors that routed signal and control voltages to different modules) without fully inserting them, so that textural changes could be made at certain points during a recital or spontaneous composition. Techniques such as these, combined with an adventurous approach and great engineering knowledge, resulted in astonishing experimental synth works.

Bruno Spoerri

Voice Of Taurus

(Gold records, 1978)

In the hands of Bruno Spoerri, the Synthi 100 got cool! Although he is said to have been inspired by classical synth pioneers like Wendy Carlos, the Swiss composer created tracks with solid backbeats, pop arrangements and jazz-funk suave. Titles like ‘Galactic Acid’, ‘Space Cantata’ and ‘Cosmotoxology’ indicated his cosmic ambition, but also suggested an awareness of fresh and emerging genres like cosmic disco. Spoerri is a true outlier: he produced and engineered his own studio sessions for Voice of Taurus, recruiting Swiss jazz drummers to play on the record, and processing alto saxophone through EMS’ pitch-to-voltage converter, and random generator. Few others approached contemporary disco and funk with the same level of experimental flair.

Stockhausen

Sirius

(Deutsche Grammophon, 1980)

Between 1975 and 1977, the renowned sound designer and composer Karl-Heinz Stockhausen used the Synthi 100 to create the electronic components of his music-theatre piece, Sirius. Music that he created could be performed by itself, without the four soloists the score also accommodates. The melodies Stockhausen composed correspond to the play’s four central characters – just one way his musical decisions were informed by the medium he was composing for. The resulting compositions bring together dialogue, synthesized and acoustic sound – a beguiling combination that is not unlike the theatre work of Harry Partch, with the Synthi 100 taking the place of Partch’s bespoke acoustic instrumentation.

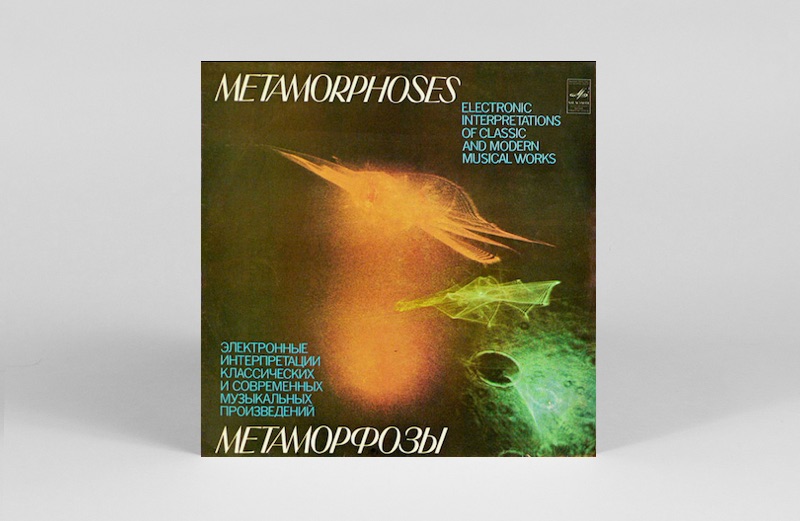

Eduard Artemyev

Metamorphoses

(Мелодия/Melodiya, 1980)

Metamorphoses is to the Synthi 100 what Switched on Bach is to the Moog IIIp. Rather than exploring the Bach songbook, composer Eduard Artemyev opted to make “electronic interpretations of classical and modern musical works”. He turned to Russian contemporaries such as the serialist Vladimir Martynov, European composers such as Debussy, and early 20th century Russian Sergei Prokofiev. The Synthi 100 that Artemyev, his studio collaborator Yuri Bogdanov, and Vladimir Martynov used, was installed at one of Melodiya’s Moscow studios. Its purchase was purportedly authorised by Alexei Kosygin, then chairman of the Soviet council of ministers. It’s unclear if state ownership had any influence on the musical direction of Metamorphoses, but the record is a diverse and enthralling collection, with closer ‘Motion’ and Martynov’s ‘Spring Etude’ both outstanding examples.

The Putney

The Putney II

(Fax +49-69/450464 records, 1995)

The Putney comprised of Ludwig Rehberg (a German distributor and sound designer who began working with EMS in German-speaking territories and once invested in its future), and the late producer and composer Pete Namlook. Also known as Peter Kuhlmann, Namlook founded his Fax label in 1992, and produced electronic music prolifically, drawing inspiration from Klaus Schulze among others. Working with Rehberg enabled the synth enthusiasts to take his experimentation up a notch. Peter described their 1995 record as “very experimental uncommon environmental ‘Krautrock’” and it is one of the definitive releases of his label’s ‘second phase’.

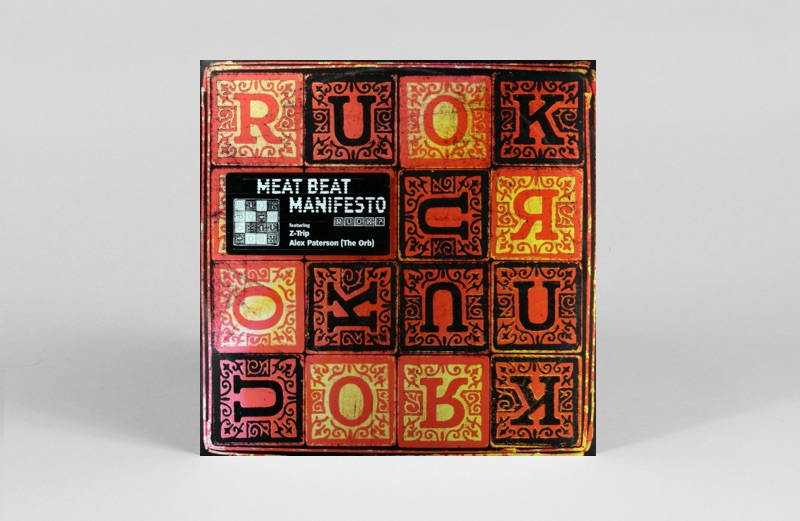

Meat Beat Manifesto

R.U.O.K.?

(Quartermass/Flexidisc, 2002)

By the time Jack Dangers came to use the Synthi 100, approaches to composition had drastically changed. Samplers, DAW’s, and MIDI control had blown the process wide open, with club and dance-orientated styles of music made in completely different ways to those of Paul Pignon and BBC Radiophonic Workshop. In light of that, R.U.O.K.? implements the Synthi 100 within a downtempo/breakbeat context. The synth’s sounds are sequenced alongside beats, samples, scratching and breaks – proving that its tones lent themselves to all manner of musical styles.

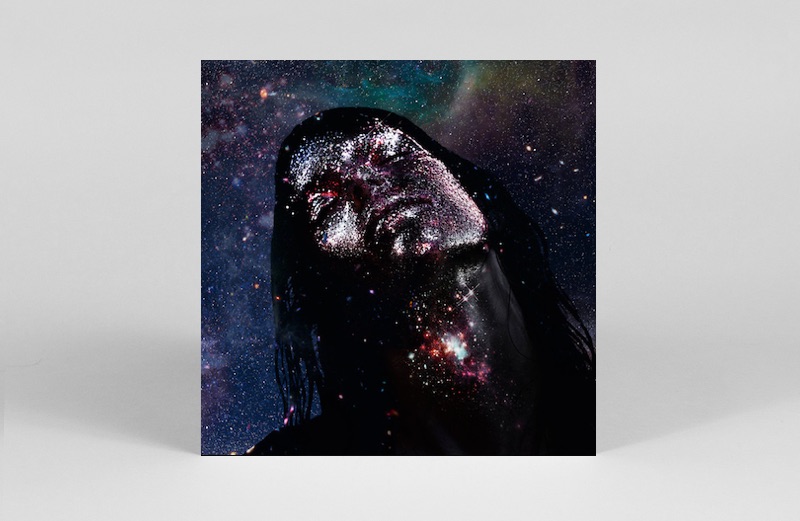

Kaitlyn Aurelia Smith

The Kid

(Western Vinyl, 2017)

Kaitlyn Aurelia Smith uses a wide range of synths on The Kid, but the track ‘Who I Am & Why I Am Where I Am’ represents a ‘a single take without overdubs’ on the Synthi 100. She programs piercing tweets over pulsing suspended chords, the oscillators gradually shifting the synchronicity within the track’s pads. You can hear the contrast between the sound she achieves on this track and other pieces on the album, which make use of more contemporary modular synthesizers and vocals.

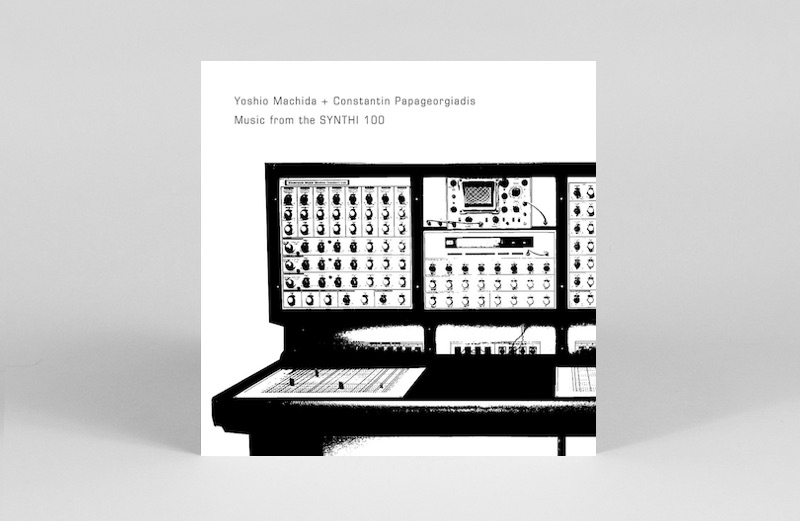

Yoshio Machida & Constantin Papageorgiadis

Music from the Synthi 100

(Amorfon, 2017)

Music from the Synthi 100 suggests that a love affair between the synth and today’s electronic producers continues. The Japanese and Belgian composers convened at Ghent University to create this album, which is entirely improvised, and exclusively features the sound of the Synthi 100. The pair also provide detailed insight into how they created the music, opting not to use a keyboard to trigger sounds, instead working side-by-side to shape and re-route the audio simultaneously. A crisp and well produced recording, it is perhaps the best recorded example of the Synthi 100’s sound capabilities.