An introduction to the electric sound of Miles Davis

Navigating the complex landscape of Miles Davis’ electric years in 10 crucial records.

Kind Of Blue might be biggest selling jazz LP of all time, but Miles Davis should be remembered for so much more than that single modal masterpiece. And while the establishment will try and tell you his greatest work falls into the two great quintets he assembled between the late ’50s and mid ’60s, so much of what came after, during his so called “electric period” and comeback in the ’80s, deserves similar scrutiny.

It’s a section of Davis’ discography which has baffled fans and newcomers alike, confounded critics and probably ruined friendships in the process. It is so thoroughly contradictory that it holds both his most accessible and most avant garde work, records that are both timeless and desperately of their time, capable of influencing musicians from across genres and generations and be shunned by the same jazz establishment that previously hailed him as the genre’s most restless innovator.

That, of course, goes without saying. In the mid ’40s he replaced Dizzy Gillespie in the hottest be-bop band on the planet with Charlie Parker and Max Roach, only to only to form his own melodic “cool jazz” sound, that would spawn the Birth Of the Cool and the quietest revolution the music would ever witness. A few years later, the first great quintet was born, and with it the million-selling Kind Of Blue (although do seek out Bag’s Groove, ‘Round Midnight and the indomitable Milestones for a taste of where this group could go).

A year later everything was up in the air once more. Coltrane was out, and some fantastic orchestral Gil Evans collaborations aside, it took Miles several years before he settled on the second great quintet – led by the powerhouse rhythm section of teenager Tony Williams, Herbie Hancock and Ron Carter. Once once Wayne Shorter replaced George Coleman was the group was complete.

The records that followed are among his greatest, departing from the standard hard bop mould towards a sparse, clear sound that cuts through most powerfully on studio albums ESP, Miles Smiles and Nefertiti. And on stage they were unstoppable. Live At the Plugged Nickel is a challenging, definitive recording, but hearing Herbie Hancock and Tony Williams go at it under a Miles’ solo on a ’64 rendition of ‘So What’ at Carnegie Hall is perhaps where this group hit its peak. Rumour has it Miles had told the band moments before going on stage that he’d given their fee for the show to charity. Needless to say, you can hear Williams and Hancock weren’t happy. As if Miles cared.

But why the preamble when we’re here to talk about the electric years? The journey that led to Filles De Kilimanjaro is one of relentless reinvention, a quest for new influences and sounds that refused to be shackled by expectation or tempered by success. By ’68 Miles was looking out from jazz for inspiration. He met with Sly Stone to get a feel for funk, saw how Hendrix shredded the guitar to pieces in front of festival-size audiences and soaked up the afro-futurist theatricals of Parliament-Funkadelic. Something had to give.

But while In A Silent Way and Bitches Brew (and On the Corner, latterly, too) have by and large had their dues, Miles’ electric catalogue can seem a daunting proposition, with moments of sublimity sometimes stranded amid a complex landscape of heavy fusion, out-there synthesis and its fair share of mainstream cock-ups. Trying to make sense of it all, we’ve picked ten records that capture electric Miles at his iconoclastic best.

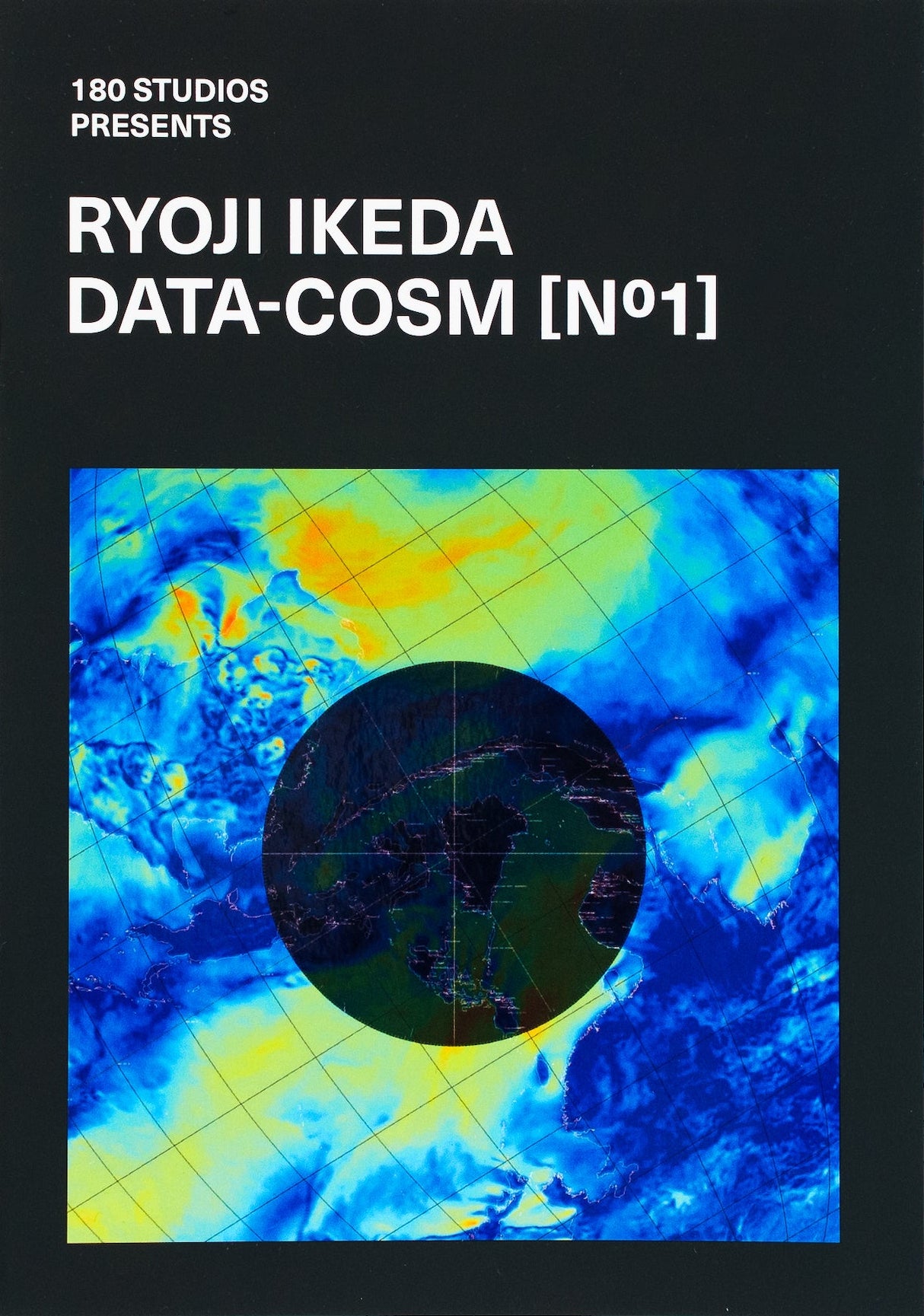

Miles Davis

Filles De Kilimanjaro

(Columbia, 1968)

If In A Silent Way is the generally accepted curtain raiser on Miles’ electric period, then Filles De Kilimanjaro is its aperitif – an amuse-bouche that hears Miles dip his toes in the water of wired instrumentation. It first emerges on track two – the tentative ‘Tout De Suite’, where Herbie Hancock’s sparse, bluesy Rhodes sets the tone for a fuller exploration of the post-bop form than had been heard from Miles to date. The extended improvisatory landscape of the track may have pointed the silent way towards Kilimanjaro’s predecessor, but there are other points on the record that are equally important, as Miles borrowed structural elements from rock concept albums to name all five parts of the suite in French.

Although credited to Davis, the final track ‘Mademoiselle Mabry’ (Miss Mabry) (recorded the month Miles married Betty O. Mabry Davis and who also appears on the cover) was in fact a Gil Evans arrangement of Hendrix’s ‘The Wind Cries Mary’, devised with Hendrix’s own input and indicative of where Davis was now seeking inspiration. The track feels its way through the melody with remarkable restraint, and the album was roundly deemed a success, notably from rock institutions Rolling Stone & Uncut as much as the jazz world. Although typically seen a as transitional record, Filles De Kilimanjaro is as complete and coherent as his most celebrated.

Miles Davis

In A Silent Way

(Columbia, 1969)

A new dawn. A chord, held for just long enough and then they were away. Williams’ shuffling hi-hats, McLaughlin teasing the keys into expression, Miles dancing between them, as the moebius-like form ebbs and flows in eternal birth and rebirth. If Kind Of Blue had been Miles’ first quiet revolution, In A Silent Way was his second – two albums that reimagined the direction of jazz with a deft change in emphasis rather than violent upheaval. Once described as “proto-ambient” (if only in texture not intention), it wasn’t quite rock (although the rock critics claimed it as their own), certainly not jazz in the way most people had known it until that point, and had perhaps even less in common with the macho bombast of fusion, the genre it had a hand in creating.

A simmering opus, it’s only half way through the album’s second track that anything like a climax is reached, a groove materialising from the somnambulant improvisations only to return to the quiet of the title’s refrain. It’s a masterpiece in restraint, atmosphere and musical empathy, recorded in a single session on 18th February 1969 and one of Miles’ most influential albums.

Miles Davis

Bitches Brew

(Columbia, 1970)

If In A Silent Way was a fluid, ultimately tranquil work, Bitches Brew thrived on conflict and resolution, an album that tears at its own fabric, no longer content to keep the peace. As Radiohead’s Thom Yorke describes: “It was building something up and watching it fall apart, that’s the beauty of it. It was at the core of what we were trying to do with OK Computer.”

Picking Yorke’s quote goes some way to exemplifying the reach of this record. For many Miles fans it was a line in the sand, for everyone else it was more like a meteorite destroying the whole beach. Out went the hints of jazz structure, in came a looser rock feel – two bassists, two (sometimes three) drummers, percussion, several pianos, brought together at short notice with little more instruction than a tempo, a feel and the snap of Miles’ fingers to indicate solos (and the famous “keep it tight”, seven minutes into the title track). At the point of creation it couldn’t have been more improvised – the kind of organised chaos more often associated with Sun Ra, but here played out the glaring mainstream.

Although not heavily edited, Bitches Brew brought new concepts of “studio as instrument” into jazz, producer Teo Macero treating the sound with tape loops,

delays, reverb chambers and echo effects. No wonder no-one knew where to put it. Simply earth-shattering, divisive, visionary stuff.

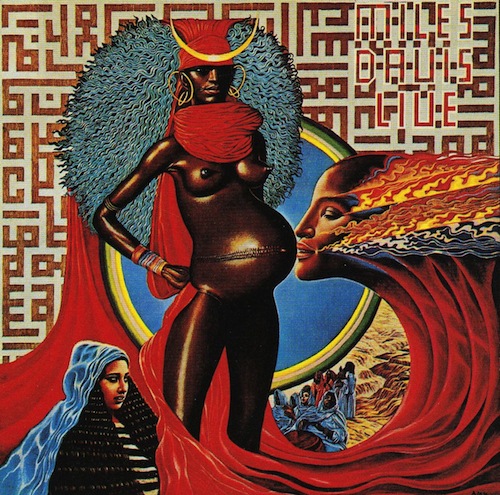

Miles Davis

Live-Evil

(Columbia, 1971)

Although continuing to employ the psychedelic art of Mati Klarwein, Live-Evil was not the follow-up to Bitches Brew it was originally intended to be. There’s a harder edge here, a more abrasive feel, due in part to the record being stitched together from live recordings taken from Davis’ appearance at DC spot The Cellar Door, producing an album which, beyond the studio wizardry resonated more heavily as jazz rock than either of its predecessors.

Here the longer pieces play out like steamy fusion jams, the shorter ballads like spiritual respites across a demanding listen that clocks in at over 100 minutes and caused critics to coin outlandish metaphors in the vein hope of chasing the spirit of the release down: it was “Hindu heavy-metal” and “barroom brawl action-funk” but also “sexually steamy and unsettling”, featuring the Brazilian flourishes of Hermeto Pascoal and Airto Moreira and the US street gospel of Gary Bartz. It was its own beast, full of complex miniatures and giant structures, a roaring, extrovert album that encompassed a central contradiction of Miles’ electric period; at once refreshingly accessible and deeply alienating.

Miles Davis

A Tribute To Jack Johnson

(Columbia, 1971)

With In A Silent Way, Bitches Brew and Live Evil under his electric belt, it’s fair to say Miles was on a bit of a creative streak when he knocked out this tribute to Jack Johnson. It was only Miles’ second score but it would go down as his best; a hot stew of hard funk, hard rock, black power and the sheer brio of boxing distilled into two side-long tracks.

Throwing a dozen gifted musicians (including Herbie Hancock, Billy Cobham, John McLaughlin) into the ring, Davis went some way to materialise on his promise to form the “greatest rock band you ever heard.” Those left wanting more should check out The Complete Jack Johnson Sessions, which was released in 2003.

Miles Davis

On The Corner

(Columbia, 1972)

Of all the outlaw items in Miles’ 45-year recording history, this is his most offensive. Where Bitches Brew lost the establishment but tapped the youth, On the Corner was completely vilified then left for dead. With 2016 hindsight it’s no wonder that, even for several decades, it was a struggle for fans. A re-examination reveals a late blooming masterpiece, an album absurdly ahead of its time – the great great grandfather of hip-hop, IDM, jungle, post-rock and other styles drawing meaning from repetition.

The four suites tangle together, swirling with a remarkable mix of stylistic ideas, from Stockhausen tape techniques to Eastern grooves, pieced together by rhythmic progressions inspired by James Brown and Sly Stone. Distinctly lacking the melodic qualities that established Davis’ reputation as a lyrical player, On the Corner’s dense, chattering percussion bangs together like a noisy New York corner – an image perfectly encapsulated by Corky McCoy’s street art.

Miles Davis

Get Up With It

(Columbia, 1974)

Little can prepare you for Get Up With It. Issued just before his dark period, the album channels Miles’ escalating instability and utter despair as his life began to slip away.

The record opens with ‘He Loved Him Madly’, a deeply emotional 32-minute tribute to Duke Ellington, written shortly after his passing. Lead by a melancholic organ, the track marches at funeral pace; the rhythm section joins ten minutes in and Davis on trumpet shows up even later. It’s one of the most haunting tracks in the Davis canon, name checked by Brian Eno as a direct influence on his ambient experiments.

Of the other tracks, ’Calypso Frelimo’ is another half hour epic, this time a soaring, maddening vision; whilst the rattling funk on ‘Rated X’ points to the future.

Miles Davis

Pangaea

(CBS/Sony, 1976)

Both Pangaea and Agharta (released a year earlier) were recorded live on one day in Osaka in 1975, a ferocious double bill that would represent Miles’ final albums of new material before his five year retreat from the scene. Pangaea documents the evening session, with Miles in out and out combat with his band, dropping pretentions of melody and harmony in favour of sprinting riffs and pummelling poly rhythms.

The first of the album’s two tracks is ‘Zimbabwe’, a feverish funk jam that whips itself into a virtuoso fury across forty odd minutes, and an experience which translates on record as one hell of a listen. Then comes ‘Gondwana’, which takes things in a more laid back direction, a deeper, more spiritual groove that rouses itself for a finale bordering on speed metal.

Of the two albums recorded that day, Agharta tends to get more shine (Beastie Boys cite it as a major influence on their 1994 album Ill Communication), at times clearer and more considered (it was the afternoon matinee after all), but there’s something so extreme and compelling about Pangaea both as live performance and a document of Miles wringing every last drop out of his trumpet before the crash. It would be ten years before he made another record worthy of the standard his electric period set.

Miles Davis

Tutu

(Warner Bros, 1986)

Miles jumped ship in 1985, abandoning a three decade partnership with Columbia Records to sign on the fat dotted line with Warner Bros. His first release was supposed to be a collaboration with label-pal Prince but he ended up dueting with Marcus Miller’s orchestra of drum machines, synths, instruments, and plugs.

Guaranteed to alienate fans, this was Davis’ all-in effort to embrace the modern studio, once again shaking apart the jazz world. Whether you call it midfield smooth jazz, awful ‘pop-fusion’, or a late period masterpiece, rarely will you hear a drum machine swing this hard.

Bill Laswell & Miles Davis

Panthalassa: The Music Of Miles Davis 1969-1974

(Sony, 1998)

Bassist and producer Bill Laswell went some distance to survey and reinterpret Miles’ largely uncharted electric period with this remix album. Translating sessions from In A Silent Way, On the Corner, Get Up With It and Agharta, Laswell stitched together four long tracks that play almost novelistically as one continuous and chronological hour-long piece. The mix finishes with a condensed but mind-expanding take of ‘He Loved Him Madly’ that’ll make you want to hear the full 30-minute opus and indeed the rest of Miles’ outlaw material.