How Leonard Cohen’s shamanistic life inspired the holiest of records

Martin Aston reflects on Leonard Cohen’s extraordinary life and storied music career, following the Canadian poet, novelist and enigmatic songwriter’s death on the 10th of November 2016.

Words: Martin Aston

There is a thought that people know their time for dying; that they wait for loved ones to arrive, or they wait for loved ones to depart. David Bowie released what proved to be his last album and then passed away less than 48 hours later. In Leonard Cohen’s case, we have no idea, at the time of writing, from what cause, but the idea that he heard about Donald Trump’s victory and simply thought, this world is no longer for me, is too good to suppress. Any rational, humanistic person would feel the same.

But someone who predominantly charted, in exquisite and poetic prose and lyrics, an existential viewpoint, on what it means to be human, someone who became a Zen monk in his sixties, living in a monastery in California, just might feel that alienation more than many. As he sang in ‘Bird On A Wire’, Like a bird on the wire / Like a drunk in a midnight choir / I have tried in my way to be free, and in light of the most powerful country on earth being headed by someone who seems more in the realm of inhuman, you wonder how Leonard Cohen took that news.

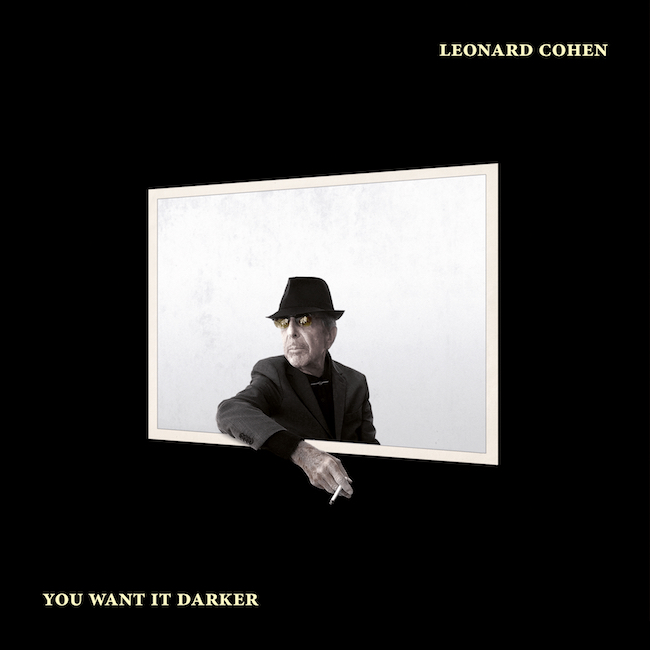

As with Bowie, Cohen had just released a new album, only last week. Its title, You Want It Darker, comes loaded with symbolism just like Bowie’s Blackstar; potentially the darkness of the encroaching end, or of the way humanity is killing itself to live, or a personal confession that, for all his songs, books and poetry, it’s impossible to understand the nature of existence? Cohen’s new title track, delivered in a deep-set gravelly tone only matched by Lee Marvin’s ‘I Was Born Under A Wandrin’ Star’, opened with If you are the dealer, I’m out of the game / If you are the healer, it means I’m broken and lame / If thine is the glory then mine must be the shame / You want it darker, We kill the flame.

The intent is clear enough. The lyric also included the line I’m ready, my lord. Another song title was ‘Leaving The Table’. His life was being taken stock of, the ‘game’ recounted, an acknowledgement of mortality that he embellished in an interview with The New Yorker when he said, “I am ready to die. I hope it’s not too uncomfortable. That’s about it for me.”

Still, like Bowie, the news of Cohen’s departure has been a shock, because of that new album, and because, despite him being ready to go, there was no news of illness, terminal or otherwise, only that he’d been in a lot of pain while making his album. He’d survived the trauma of losing a considerable amount of money ($9.5m, roughly £5.4m) to his former manager, that forced him out of monastic retirement to play a series of concerts for the first time in decades, to refill the coffers, a new ‘career’ that Cohen appeared to enjoy as he carried on playing more shows, and releasing new records. From releasing three albums in 19 years (between 1992 and 2001), he released three in five years, between 2012 and 2016. He was still in the game.

My own initial relationship to Cohen’s work was, if in no sense troubled, then a little distant. Bowie, in the guise of Ziggy Stardust, was my shining star, my shaman, and I went down the road of glam, punk and new wave, (and went back via The Velvet Underground, and the colour-saturated world of psychedelia) and found the singer-songwriter confessional in the form of James Taylor and Carole King to be limited, drab and indulgent by comparison; and though Cohen had a more involving, darker, uncanny energy, he still sounded too austere, too monochrome for my limited appreciation.

If I was to indulge in “music to commit suicide to” as one friend described Cohen’s solemn, intense persona, in voice and arrangements – crazy to think of that now, since his words are so full of life as well as an appreciation of mortality – it would be the sweeter, romantic, doomed English existentialism of the late Nick Drake to this more impenetrable, and clearly older (he was already 33 by the time of his debut album Songs Of Leonard Cohen), and living, Canadian.

By the time I discovered Cohen songs as epochal as ‘Joan Of Arc’ and ‘Avalanche’ (both from 1971’s Songs Of Love And Hate, his third album) still my two favourites, and came to appreciate the equal deathless beauty of ‘Famous Blue Raincoat’, ‘Bird On A Wire’, ‘Sisters of Mercy’, ‘So Long, Marianne’ and ‘Hey, That’s No Way to Say Goodbye’, he’d been recording for over 25 years, and released seven albums, and represented, for many, a figure every bit as shamanistic as Bowie, but in a different age, and way.

The consciousness-raising Sixties, when a generation turned inward to expand outward, to overcome the traumas of World War Two and the ‘keep calm and carry on’ stunted mindset of the Fifties, needed figureheads, and with literary heroes in the Beatnik era – Kerouac, Burroughs, Ginsberg – Leonard Cohen articulated the same sense of freedom on the page, and in his experiences, and travels. He’d also recorded, on his debut album, ‘So Long, Marianne’, which documented his affair with the married Norwegian woman Marianne Ihlen, who he met when he’d escaped the damp weather of his adopted city of London (and before that, his home city of Montreal) for the Greek island idyll of Hydra, where Cohen had bought a house, and composed many of his early classics, in book and song form.

It was Hydra where I had my most memorable Leonard Cohen ‘moment’; I was commissioned in 2014 to interview his son Adam – the producer of You Want It Darker – on the island, where he was spending the summer, though he admitted his dad hadn’t been to Hydra since the early Nineties, shunning the attention of fans and tourists drawn there because of him. It was space, and relative silence, to articulate thought and write poetry (and soon, songs) that he craved. “Dad fell in love with Hydra,” Adam told me. “It corresponded to a romantic notion of who he was and wanted to become, and to a lifestyle so antithetical to how he was raised [in Montreal] – Victorian, uptight and freezing cold. We’re a family of sun-worshippers, but you don’t have to be that specific an animal to understand how extraordinary beautiful and easy this place was – and is.”

Given Cohen Senior lived in a monastery in the Nineties, Hydra would have been his first refuge. “It was quiet enough for work, and social enough for reprieves from the tyranny of that work. [Novelist] Henry Miller was on [neighbouring island] Spetses, there were painters and poets here. He wasn’t looking for San Tropez, put it that way.”

Despite Leonard’s absence, the humble décor of what was once a fisherman’s cottage remained, including the small monastic-style room at the back that still housed his writing desk. A painting of the artist as a young man was joined by other telling details – a book of Lorca plays, Thomas Mann’s post-modern ‘medieval’ exploration of evil and magic The Holy Sinner and a thumb piano in one corner cupboard, a backgammon set and bowl of shells on a weathered wooden coffee table. Adam recalled his father writing at the kitchen table too, “hundreds of times, in his underwear with his guitar, and chain-smoking.”

His dad would, with creativity unleashed and escalating sales and fame, move around the world, and though his work became less audibly bleak – such as 1977’s Death Of A Ladies’ Man, a collaboration with the producer Phil Spector – he never lost that sense of gravitas, of someone who had seen aspects of darkness, sensed what was askew with human relations, and all of our expectations carried with us since birth, and the impact on our social and sexual relationships, and both the burdens and privileges of spirituality and religion. There were six more albums between 1979 and 2004, including Death Of A Ladies’ Man’s more fleshed-out band sound, and I’m Your Man, where Cohen was hitched up, incongruously, to the sound of synth-pop – though we’re not talking Erasure here, more a moody timbre several degrees to the left of Pet Shop Boys, and the rich backdrop, as with Spector’s production, suited his voluminous delivery.

Two tracks from I’m Your Man, ‘First We Take Manhattan’ and ‘Tower Of Song’, were respectively covered by R.E.M. and Nick Cave (who had already covered ‘Avalanche’ on his 1984 album From Her to Eternity) for the 1991 tribute album I’m Your Fan: The Songs Of Leonard Cohen, the first such record to promote his back catalogue to a new post-punk generation.

The tribute album’s finale was John Cale’s version of ‘Hallelujah’ which found another lease of life in, of all things, the film Shrek; Jeff Buckley’s subsequent cover (in Cale’s style more than Cohen’s) included on his debut album Grace gave the hymnal ‘Hallelujah’ more momentum, to the point that the song was covered on American Idol in 2008, while the UK’s Christmas number one that year was X factor winner Alexandra Burke’s version, with Buckley’s cover at number two, and in 2012, the book (The Holy Or The Broken: Leonard Cohen, Jeff Buckley, And The Unlikely Ascent Of ‘Hallelujah’, by Alan Light) was published.

By then, Cohen has emerged from monastic isolation on Mount Baldy, driven out by his thieving ex-manager, and had been on tour for five years, overcoming his collapse on stage in 2009, supposedly from food poisoning, and only stopping in 2013.

A final resting stop has now been reached. Fortunately, by now, Cohen has been covered by so many performers across so many genres, perhaps only outdone in this regard by Bob Dylan, that he’s easily escaped the shackles of being called ‘the Godfather of Gloom’, and there was a lot humour in his words too, and a twinkle in the eye, once he’d also thrown off the shackles of depression that haunted him before he took up Zen Buddhism. Though some who want it darker – or worse – will find solace in his sound and vision, he is much more of a life-saver, with an irrevocably positive gift, by revealing truths, no matter how difficult they might be. As he sang in ‘Anthem’ (from his 1992 album The Future), “There is a crack in everything / That’s how the light gets in.”