Published on

April 19, 2017

Category

Features

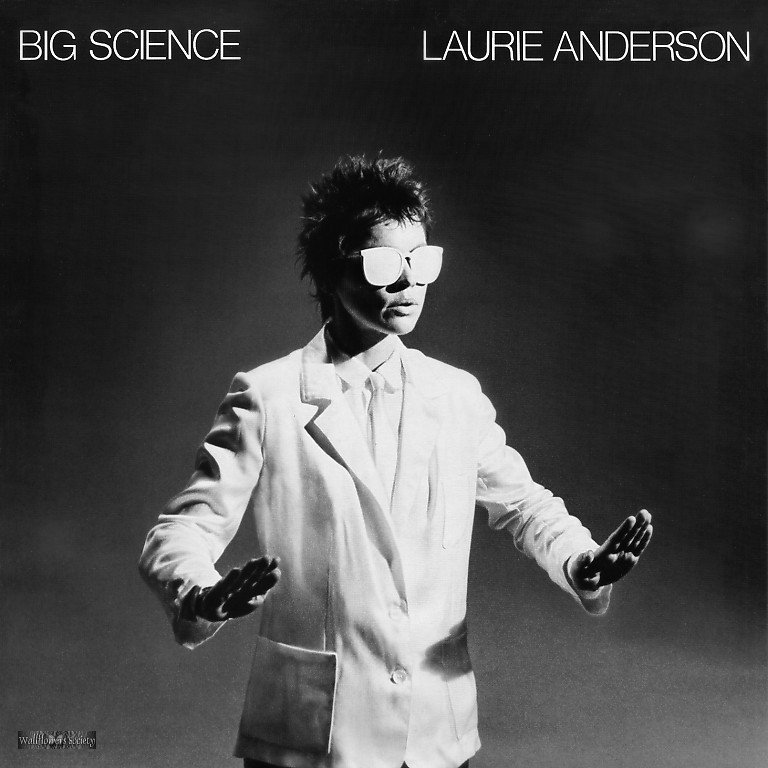

35 years ago today, Laurie Anderson unleashed the era-defining album Big Science. As well as birthing synthesised art-rock, it now seems now to have the quality of eerie prophecy, argues Vivien Goldman.

Sometimes we all want to shed the shackles, run with the wolves, and make that jagged howl, it’s not a For Females Only trait. We all contain the atavistic and the futuristic. Was it Laurie Anderson’s use of howling wolves as fellow harmonisers on the title track that so endeared 1981’s Big Science to a generation?

The gamine, androgynous multi-instrumentalist and synthesiser experimenter recently performed one of her live gigs for dogs in Times Square; The Guardian admired its use of low frequencies. In last year’s movie/music suite, Heart of a Dog (shortlisted for the 2015 Oscar,) she processed mourning a canine friend and implicitly too, her husband and companion of years, Lou Reed.

This lack of species-ism exemplifies Anderson’s blindness to boundaries, a trait that, combined with a whole harmonic convergence of imaginative skills, helps ensure her own singular and sustained vibration in pop. Surprising everyone, the pop success of freak UK hit 45, ‘Oh Superman,’ gilded Anderson.

When she married Velvet Underground founder Lou Reed in one of music’s most sustaining partnerships, they came together as creative equals. On another, more artistic note, current enthusiasm for its 45th anniversary shows that Anderson also picked cannily when she distilled her 4 ½ hours-long orchestral and multimedia performance, The United States of America, into the comparative brevity of Big Science’s eight pungent tracks.

With her postmodern pixie haircut – allegedly first snipped by Winston Tong, the singer of West Coast art-rockers, Tuxedo Moon — Anderson was a fresh paradigm, who programmed to her own drum sample. Perhaps anniversaries act as too easy an anchor in our chaotic culture, but Big Science deserves its re-assessment. It seems now to have a quality of eerie prophecy.

The album’s anniversary is being celebrated as a birth of synthesized art-rock – pace Brian Eno — but let’s also dig Big Science as the harbinger of intersectionality that it is, sizzling somewhere between music and drama, social observation, politics, history, projection and humour; and with its sound just as unexpected, melodies, more abstract soundscapes, and for at least some among us, the pleasing and unexpected skirl of the bagpipes on the very funny ‘Sweaters.’

On the track ‘Big Science’ itself, her gentle vocal persuasion counterpoints a dirge of a drone, that could recall the harmonium and voice of Nico, Reed’s early bandmate/muse – except that Anderson’s tough fragility is tones apart from Nico’s deadpan, near-dead affectlessness.

Something about the brutish optimism of the early 1980s prompted the frequent use of the word “Big” (Disclosure, I co-created a TV music show back then called Big World Café and noticed we were part of a “Big” Moment before we said Moment, including this LP and the Tom Hanks flick.) The title’s nod to Science acknowledges the dream of technology as hope – and its limits.

There’s a suggestion of the era’s hysterical expansiveness in Anderson’s butterfly-wing-subtle deliveries, fluttering fast through meta levels of wry wit and seismic sighs at the human condition. Above all, right now, it is the chilling suggestion of creeping authoritarianism that makes Big Science feel so scary timely. Modestly lilting, the folksy intimacy with her characters makes her odd rigor all the more powerful. Take the airline pilot of opening track, ‘From The Air,’ professionally, detachedly and yes, robotically, steering the passengers through the imminent Big Crash. Is this the inner voice of the guardians of nuclear buttons in today’s Lukewarm War?

Beyond the famous early-girl-with-synthesiser aspect, perhaps the biggest surprise is how the emerging trends of the time, which proved durable, are so clearly limned: the neo-African kalimba-like sound, and above all the experimental fireworks of free jazz, sparkling off in several directions.

The entire exercise is steeped profoundly in the harmolodic concept of Ornette Coleman, a figure who also loomed large in her marriage; L&L, as Lou’n’Laurie called themselves, were regulars at Ornette soirees and events; he represented one of the few key constants and touchstones in their select pantheon. The biting spoken verse of the young Coleman’s wife, firebrand activist poet Jayne Cortez, also seems to resonate deep inside Anderson’s polished rage.

They called it art-rock but it is simply, timelessly, avant-garde.

The ultimate triumph of Big Science, and the key to Anderson’s longevity, resides beyond her mind and music’s admirable keen-ness, giddy hilarity and somber empathy. It is that growling animal thing, the wolf howling within the minimalism, rendering the supposedly cold synthesizer into an all too human instrument.