An introduction to Madlib in 10 records

A genre-hopping, identity-switching, crate-digging guide to the many faces of Madlib.

Getting into Madlib means getting into dozens of other artists – some of whom are also Madlib. Otis Jackson, Jr. has taken the artistry of sampling to an extent that he can use it to explore not just other areas of music, but other ways of presenting himself – through alter egos, collaborations, and mixes that blur the lines between sampling and traditional musicianship. Spend enough time digging through crates and pulling apart other peoples’ music, and it’s not just understandable but insightful to try and rebuild it from multiple perspectives. Madlib’s whole legacy, for more than twenty years, has been built around just that.

Even with all his excursions into cross-genre pollination, time-warping postmodernism, and identity-obscuring deconstruction, Madlib’s central sonic persona is still easy to grasp: he’s rooted in the classic hip-hop sampling techniques of the late ’80s/early ’90s, even if he runs some unlikely styles through it – dub reggae, Brazilian pop, and the more abstract corners of jazz have been more integral to his blueprint than they have for just about any other artist to helm an SP-1200. And his sense of musical adventure has taken him plenty of far-flung places – these ten albums are just the beginning of a long, unpredictable itinerary that’s taken him from Tha Alkaholiks to Kanye.

Lootpack

Soundpieces: Da Antidote

(Stones Throw, 1999)

Madlib was one of a number of West Coast producers who had more interest in revamping underground East Coast sensibilities for Cali vibes than in following in the g-funk foosteps of Dr. Dre and DJ Quik. And as Stones Throw emerged as a label simpatico with the battle-hewn mindset of L.A. indie showcase/collective Project Blowed, Lootpack built off a near-decade-long body of work to provide one of the young label’s first bonafide classic full-lengths in 1999. The sample-slayer bonafides are made clear from the start – the titular intro track features a seemingly disjointed Prince Paul-style collage of soundbites seguing into “an appointment with Dr. SP at 1200 hours” – and it’s evident throughout the album that Madlib as a producer is intent on taking the Pete Rock style of jazz-informed loops and headnod drums into more esoteric lo-fi turf.

It’s also a quick-moving listen for an album with two dozen tracks: a who’s who of Cali fellow traveler guest spots (Dilated Peoples, Tha Alkaholiks, M.E.D., Madlib’s brother Oh No) and an attention-deficit-stifling array of beats back up Wildchild and Madlib’s zero-bullshit verses. And even at this early phase, a lot of Madlib’s familiar techniques and traits were well in place – check out his producer-as-antiquarian anthem ‘Crate Diggin” (“Diggin’ for them unordinary soundin’ loops/Even if it’s not clean to thee”), or an early appearance of his squeaky-voiced alter ego Quasimoto on ’20 Questions’.

Quasimoto

The Unseen

(Stones Throw, 2000)

Madlib’s first solo album was released just a couple weeks less than a year after Soundpieces, yet it already came across like a forward leap – no slight to Wildchild, but it turned out that Madlib’s best lyrical foil was himself. Alter ego and album headliner Quasimoto is a big part of that breakthrough, an instantly iconic voice that, in the form of a brick-tossing, vaguely anteater-esque creature designed by in-house art director Jeff Jank, would soon become a central character in Stones Throw iconography. The high-pitched Quasimoto voice originated as an early attempt on Madlib’s part to disguise his mumbly deep baritone, but it also feels like a striking complement, tossing out back-and-forth conversational hooks and amplifying Madlib’s own philosophies into Fantastic Planet-size cartoon freakouts.

There’s a good mix of conscious-rap uplift (‘Real Eyes’), diabolical threats (‘Put a Curse on You’), cop-mocking crime stories (‘Low Class Conspiracy’), and straight-up record-geek anthems – ‘Return of the Loop Digga’ is the spiritual sequel to Lootpack’s ‘Crate Diggin” that goes even deeper into Madlib’s record store archeology (“Would you happen to have any, uh, Stanley Cowell? Like 1970s stuff… I think his stuff is on Strata-East or something”) as Lord Quas details the modus operandi. The beats bear this out: Melvin Van Peebles spoken-word routines mingle with Quasimoto’s own comic asides, spiritual jazz and psych-funk deep cut samples set up alley-oops for knowingly deployed old school breaks (check for that ‘Impeach the President’-via-‘Top Billin” drop in ‘Basic Instinct’), and the whole atmosphere is perfectly calibrated to engage both high-energy head-nods and blunted zone-outs.

Madlib

Shades of Blue: Madlib Invades Blue Note

(Blue Note, 2003)

By 2003, Madlib’s reputation as one of hip-hop’s top-tier jazz fiends was enough to land him a gig remixing tracks for Blue Note, a prestige label that had already been on nodding terms with its influence on sample-based production dating back to the early ’90s and their Blue Break Beats series. Like those collections, Shades of Blue draws in part from Blue Note’s late ’60s/early-mid ’70s when soul jazz reigned supreme, the same boom-bap-heavy material that provided so much of the structure of classic early ’90s NYC hip-hop and subsequently fell into Madlib’s crates on the other coast.

He works well within the classic structures of those breaks, maintaining the original spirit of songs like Gene Harris & His Three Sounds’s ‘Book of Slim’ (the scratch-heavy bricolage of ‘Slim’s Return’), Donald Byrd’s ‘Stepping Into Tomorrow’ (extended into a meditative haze with a foreshadowing MF DOOM cameo), and Ronnie Foster’s ‘Mystic Brew’ (redubbed ‘Mystic Bounce’ and given an uptempo disco-boogie revamp to set it a world apart from A Tribe Called Quest’s ‘Electric Relaxation’ flip). But he shines through the older material, too – particularly a remix/cover of Horace Silver’s ‘Song for My Father’, a partially-live performance featuring members of Connie Price & the Keystones and given an enjoyably off-kilter vibe from loose-but-spirited contributions by bassist Monk Hughes, keyboardist Joe McDuphrey, and percussionist Malik Flavors. Those last three musicians, by the way? Let’s just say none of them have ever been spotted in the same room as Madlib.

Jaylib

Champion Sound

(Stones Throw, 2003)

Jay Dee – later J Dilla – was dearly respected by pretty much everyone who worked with him. But the artists who he helped realise new ideas respected him the most, a respect that was often repaid with an exchange of influence. Jay and Madlib were both producer/MCs with underground followings, but they still diverged in important ways, from their spheres of influence (Dilla’s Soulquarian hip-hop/neo-soul reach vs. Madlib’s miles-underground woodshedding) to their contemporary styles (clean and glowing vs. hazy and dubby). But they were mutual followers, and once they started trading beat tapes between Detroit and L.A. they started working out the structure of their teamup on Champion Sound – and the kinds of mutual interests and concepts that would later inform both J Dilla’s Donuts and Madlib’s Beat Konducta mixtapes in the near future.

The gimmick seems simple enough – Dilla raps over Madlib beats, and vice-versa, alternating tracks between the two for a deliberately contrasting yet gradually unifying vibe. They wind up meeting each other halfway, with Dilla’s digital funk mode hissing and sparking a little grimier than usual and Madlib’s jazz-laced eccentricities pared down into the most no-nonsense heavy-hitting beat-driven side of his production. Their lyrical styles complete the fusion dance: Madlib’s understated flow and stoned wit make Dilla’s beats seethe inside a hotbox, while Dilla’s club-hedonist lyrics bring Madlib’s beats from the musty record stacks to the VIP section.

Madvillain

Madvillainy

(Stones Throw, 2004)

There’s not much that can be said about Madlib’s teamup with MF DOOM that hasn’t been said before: long story short, it’s a top-of-their-game teamup that was legendary even before it came out (thanks in part to a release-date-sabotaging promo leak in 2003). Both DOOM and Madlib were of a similar mind as producer/MCs attuned to both the spiritual depth and the comic-book weirdness that hip-hop could bring, and two artists who were uniquely idiosyncratic on their own became the most compatible collaborators of the decade this side of Kanye and Hova. A favorite of public-radio aesthetes and underground hardcore heads, artists and weirdos, all-day smokers and sober listeners who found the music itself narcotic, Madvillainy remains one of the biggest bonafide successes both artists and their label had ever experienced.

It’s not hard to hear why: it’s weird, but weird in a way that feels somewhere between timeless and prescient. Madlib’s beats wrangle the old traditions of boom-bap into other forms (Skulk-lurch? Weave-jab? Glide-bounce?) that challenged DOOM’s ear for rhythm and got a fistful of anthems in return. Madlib went nova here: the hopped-up step-lively piano jazz of ‘Raid’, the schmaltz-turned-sinister bossa of ‘Curls’, the Benihana’d vintage R&B banger ‘Fancy Clowns’, and that bulletproof psilocybin soul-jazz ending run of ‘All Caps’/’Great Day Today’/’Rhinestone Cowboy’ alone put most of his indie peers’ formalism to crying shame.

Sound Directions

The Funky Side of Life

(Stones Throw, 2005)

It’s not rare for someone who works heavily with samples to have a firsthand knowledge of the musicianship that went into the music being sampled – just ask funky drummer J-Zone, or classically trained violinist Dan the Automator. Madlib’s multi-instrumentalist side emerged early in his solo career; just check out 2001’s Angles Without Edges, billed under Yesterdays New Quintet, to get a sense of what he could do as a multitracked one-man bass/drums/keyboard/vibes ensemble. So by the time The Funky Side of Life dropped under his Sound Directions alias, he’d earned his reputation as someone who could reconstruct and conduct live music with the same feeling he could build a beat.

Like his live-band collaborations on Shades of Blue, Sound Directions has the backbone of instrumental input provided by the pseudonymous likes of keyboardist Morgan Adams III and bassist Derek Brooks (Madlib aliases both, along with his government name, Otis Jackson, Jr., on various percussion and keys). Members of Los Angeles-based funk project Connie Price and the Keystones provide the horns. And in a coup breakbeat fiends would lose their minds to get, the rhythms are held down by “Sloppy” Joe Johnson, whose ironic nickname belies the fact that his gig playing on Dexter Wansel’s 1976 fusion classic Life on Mars album landed his airtight drumming in the pantheon of classic breaks. The Funky Side of Life‘s itinerary of eclectic covers – Marcos Valle’s MPB reverie ‘Wanda Vidal’, Lesiman’s ’70s Italian library-funk obscurity ‘Play Car’, David Axelrod’s psych-jazz masterpiece ‘A Divine Image’ – isn’t just a sly reverse-engineering of Madlib’s break-source record collection. It’s a fun, gritty, minor soul-jazz classic on its own.

Madlib The Beat Konducta

Vol. 5-6 A Tribute to…

(Stones Throw, 2008)

Madlib’s first Beat Konducta mixes – 2005’s Vol. 1-2: Movie Scenes – were created roughly around the same time as an ailing Dilla was putting Donuts together. But the mutual acknowledgement, influence, and friendship between Madlib and J Dilla was evident almost immediately and lasted as long as it could – from their earliest Jaylib collaborations all the way through Dilla’s passing and on to the preservation of his legacy. The release of Donuts, Dilla’s crowning final statement and one of the finest instrumental hip-hop albums ever made, would grow to define the Stones Throw catalogue more than almost any other album released that decade. And few tributes to Dilla’s music and his legacy felt as the two-part Beat Konducta series that Madlib built off the memories and ideas stirred up by their past collaborations.

You can hear the stylistic acknowledgements right off the bat, with the mixes’ emphasis on the kind of choppy yet fluid, bass-heavy soul eclecticism Dilla traded in. It’s also peppered with direct references: the Mantronix air-raid siren that became a Dilla trademark, namedrop samples lifted from Champion Sound, the same “I don’t know” James Brown soundbite from ‘Make It Funky’ that Dilla built Slum Village’s ‘I Don’t Know’ around. But above everything else, there’s the pure emotion that Madlib can wring from these juxtaposed samples, of remembrance and re-envisioning, debt and gratitude, humour and sorrow.

Madlib

Medicine Show #5: The History of the Loop Digga, 1990-2000

(Madlib Invazion, 2010)

Before the early Lootpack singles started building up in the late ’90s, Madlib’s production discography was scarce. He did stray beats for Tha Alkaholiks (‘WLIX’ from 1995’s Coast II Coast; ‘Tore Down’ and ‘Killin’ It’ from 1997’s Likwidation) and Boot Camp Clik members O.G.C. (‘Flappin’, off 1996’s The Storm), and the vast majority of early impressions didn’t really start gathering momentum until Lootpack’s first singles on Stones Throw in ’98. So in the midst of the massive dozen-plus-album series of archival releases, collaborations, mixes, and experiments that Madlib dubbed Medicine Show, he dropped this early-years collection that more or less clarifies the come-up years where he transformed from a workmanlike boom-bap practitioner to a full-fledged iconoclast on the verge of genius.

Of course, history is wildly blurred here: except for the tracklist’s order relegating the recordings from his early ’90s collective Crate Diggas Palace to the end, the old beat tapes Madlib pulled from his archives are jolted out of chronological recognition. Some tracks are mixed and cut into a continuous wave of music that hints at early-phase, no-nonsense versions of his beats and prototypes for tracks he’d later give to others or put on his own records. Others are left to unspool at their own pace, fragments of ideas that glint flashes of recognition. But the exact whens and wheres are kept close to the vest, ideas lifted from what could be another time but are contextualized into the head-swimming lo-fi continuum of all Madlib’s work. Even in a collection of work explicitly labeled as early and formative, time feels like an illusion.

Madlib

Medicine Show #7: High Jazz

(Madlib Invazion, 2010)

Nearly a decade after Madlib put together his “Yesterdays Universe” assemblage of quasi-incognito jazz-musician alter egos, he expanded their names, identities, styles, and methods into a nearly impossible-to-parse squadron of imaginary players. Strikingly enough, it genuinely sounds like a multi-artist compilation, a culmination of a couple decades’ worth of accumulated fascination and knowledge and work spread out across a plethora of identities. This time around, his ensemble’s drawn in more and more real-world musicians to join him – including Azymuth drummer Ivan Conti, drummer/producer Karriem Riggins, and Roots member/pianist James Poyser – along with a dizzying array of genre exercises from electronic free jazz to cosmic post-bop to Latin fusion.

There’s a massive centerpiece from Yesterdays New Quintet, reprising their Wonder-homage Stevie Volume 1 mode for a recording of ‘Don’t You Worry Bout a Thing’ (allegedly) taken from a 2000 “live performance.” The Jahari Massamba Unit rolls through a beatific classic bop performance of ‘Pretty Eyes’ that glides like late ’60s Ahmad Jamal. The Kenny Cook Octet’s title track burbles through Headhunters-esque funk crossover that perfectly captures both the sound and the intangible feel of 1974. And ‘Tarzan’s Theme’, the Big Black Foot Band’s collaboration with The Black Spirits, is an Afrocentric spiritual jazz/spoken word piece in the righteously conscious mode of the Last Poets and the Watts Prophets.

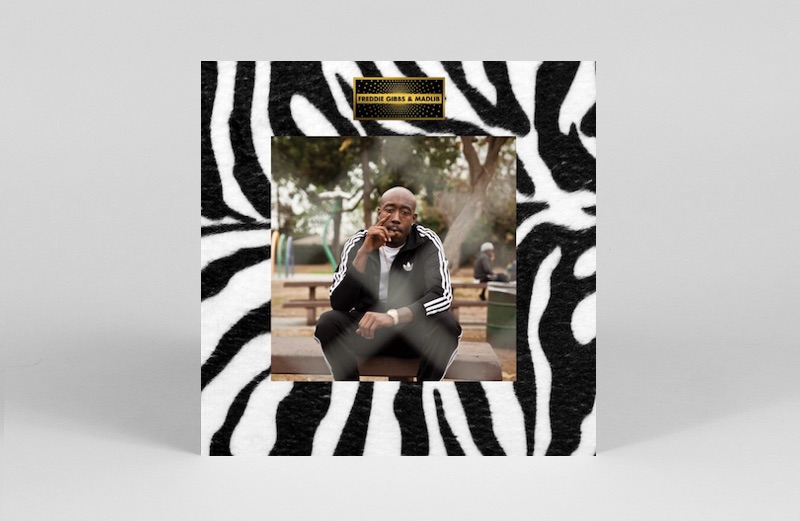

Freddie Gibbs & Madlib

Piñata

(Madlib Invazion, 2014)

It shouldn’t be that unlikely a pairing for Madlib to team up with a gangsta rapper of Freddie Gibbs’s calibre – Gibbs is as popular among the indie-crossover set as he is among the hardcore heads who checked for the Gary, Indiana MC dating back to his early mixtapes. And Madlib’s versatility behind the boards means he’s more than cut out for a classic-style yet still recognizsbly idiosyncratic take on the kind of beats that could accommodate Gibbs’s slick-flowing Chicago-adjacent drawl – or Danny Brown’s manic Detroit yelp (‘High’), or Scarface’s Texas-gangsta elder statesman reflections (‘Broken’), or Raekwon’s calculating narratives (‘Bomb’), or the L.A. clarity of OFWGKTA alumni Domo Genesis and Earl Sweatshirt (‘Robes’). A decade after Madvillainy, Madlib proves on Piñata that he can make just about any MC sound at home – and that the last couple generations of hip-hop artists aren’t as confined to the vagaries of regional affiliations and radio-ready marketing as they used to be.

Plus, it’s just plain across-the-board brilliant as a portfolio of beats. ‘Thuggin” might be one of Madlib’s all-time top five productions, a turn-of-the-eighties slice of de Wolfe British library music perfectly exploited for the ethereally wistful qualities of some semi-anonymous studio hand’s quasi-Floyd guitar riffs. ‘Uno’ distorts the diamond gleams of New Age synth-prog until it sounds tailor-made for Monte Carlo window-rattles. And the stripped-down soul of ‘Harold’s’, ‘Knicks’, and ‘Shame’ put him in the kind of rarefied class that made his funk-filleting gig doing ‘No More Parties in L.A.’ for Yeezy’s The Life of Pablo a natural destination. This is Madlib’s purest foray into mainstream hip-hop as a traditionalist – and that he comes out of it still at the vanguard of the genre’s avant-garde possibilities is all a veteran producer could wish for.

Madlib plays Sunfall festival in London on 12th August and is headlining one hell of an after party at XOYO, which you can grab tickets for here.

Main image: Carl Pocket