Published on

April 21, 2017

Category

Features

The fascinating story behind the capital’s much-loved record shop.

‘Why Dalston is the coolest place in Britain,’ so says the property website movebubble, seemingly without any sense of irony or self-awareness. As greasy spoons make way for brunch bars and new money overtakes old community, the mainstays that represent Dalston’s heritage are a dying breed, but amid the changing face of east London and down a narrow backstreet lies Eldica.

Bradbury Street juxtaposes Dalston’s battling demographics. On one side there’s Eldica, Nigerian eaterie Asorock Express and The Dalston Jazz Bar. On the other, and almost directly opposite Eldica’s doors, lies the type of high-end burger chain food bloggers and hungover locals enthuse over. Eldica however exists as a sort of homage to Dalston’s past, one that after 17 years has become more of a community cornerstone than just a simple retailer of dusty, second-hand records.

“Back in the day this street was a total no-go area,” says Andy Westbury, buyer and owner of Eldica alongside his wife Annie. “When we first opened DJs who come from Los Angeles wanted to leave before it got dark and cab drivers would never pick up or drop off here. It’s trendy here now though, but the shop’s not a trend. More than anything I want to keep it real.”

Opening their doors in the year 2000 and named in tribute to Annie’s grandmother Eldica Joachim who passed away the year prior, Eldica started life as a tiny mirror and mosaic store three doors up the road under Annie’s sole ownership. Today however, Eldica’s expertise lies in music of black origin from across the globe. Aside from perhaps a few recent reissues and possibly a rogue hip-hop LP here and there you’ll be hard pressed to find anything released after the mid-’90s.

Instead, Eldica looks to Dalston’s diverse multicultural makeup to inspire its hand-picked selections. Their records are meant for warmer climates, where everything from rare reggae, funk, soul, calypso and Bollywood to Swedish porno music and jazz freakout all fight for space in the snug confines of Eldica.

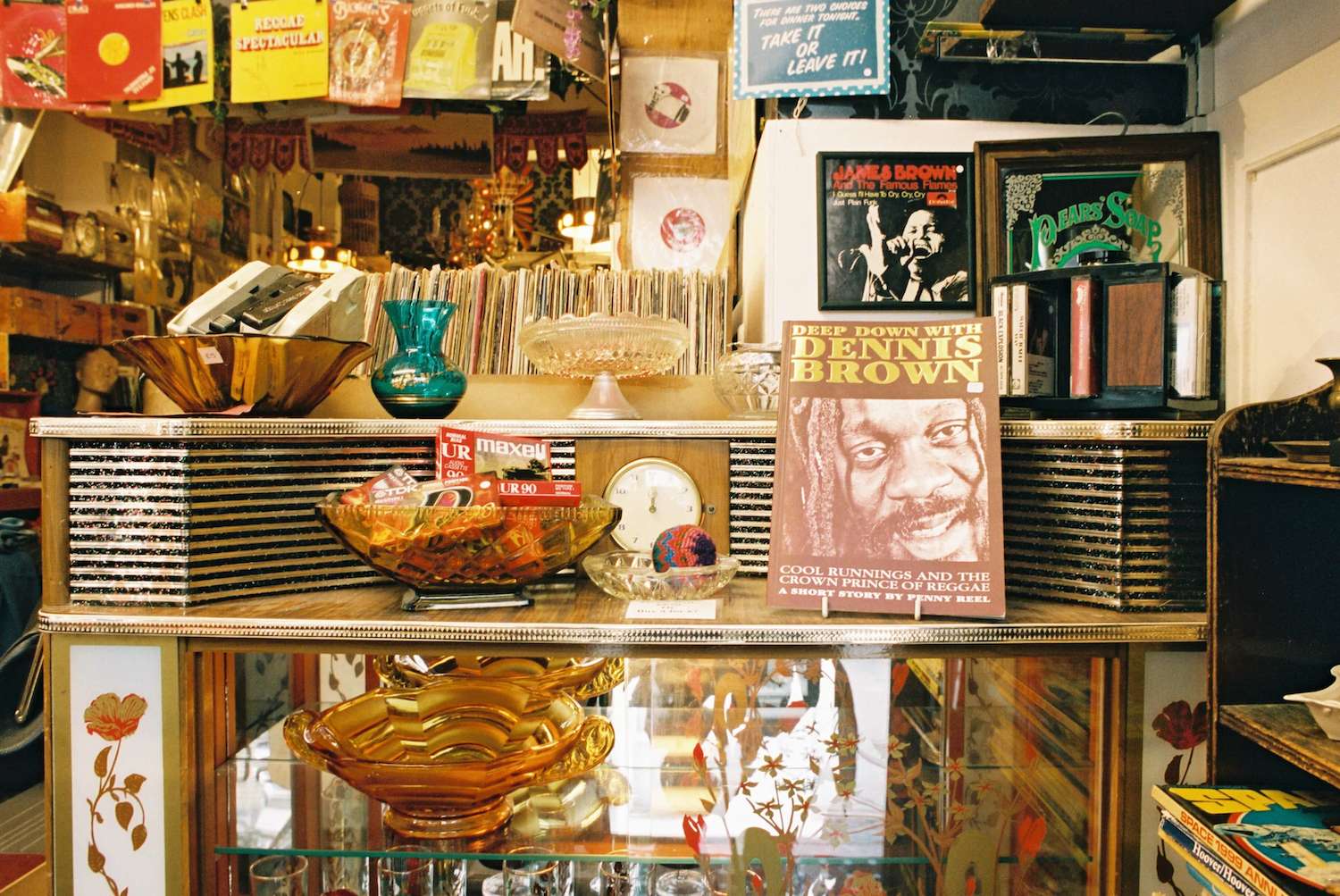

“I’m not saying no good records come out now… but older, nicer and more attractive stuff just appeals to us,” says Andy. From that mantra, Stepping into Eldica is similar to walking into your Grandma’s front room, complete with floor to ceiling curtains, crystal chandeliers and vintage collectibles. Photos of James Brown adorn the walls and old record players circa who-knows-when balance precariously across the store, while seasoned collectors share ridiculously specific factoids about records you’ve probably never heard of. “

If I think back to the ’80s record shops were more like Aladdin’s caves,” he continues. “There wasn’t any wooden floors or IKEA furniture, there was stuff everywhere to get your attention so that’s why we are the way we are. We haven’t changed and we’re part of the community in that aspect. The area has, but we’re the same business we always were.”

As a one time member of ’90s hip-hop rave outfit 2-Mad Andy’s self-described vinyl addiction began from an early age. “We were almost on Top Of The Pops,” he says, speaking of the time 2-Mad’s 1990 track ‘Don’t Hold Back The Feeling’ almost landed him a prime time TV slot.

“We reached number 41 in the charts once and if we were any lower we would have been on the show. I was shitting myself, literally praying that it didn’t happen…” Over time, and thanks to some relatively easy convincing from Annie, Andy’s collection of 45s and 12” soon began to creep onto the shelves as they realised that his rarities peaked the interest of the Caribbean old-timers and former-Jamaican sound-system DJs of Dalston.

As records quickly began to take up more room in the store vinyl soon became their main focus, and with a baby on the way in need of a makeshift workspace nursery, they were eventually forced to move to their current location. “It really is a family business in the truest sense of the word,” Andy goes on to say. “I suppose that’s quite unusual in this day and age…”

As a family business Eldica’s lineage dates back much further than Annie and Andy taking on the lease at the turn of the millennium. During a period of post-war regeneration the store’s inspiration Eldica Joachim first emigrated to the UK from Trinidad and Tobago in 1946 with her husband Peter, who sought to further his career as a musician.

Throughout the late-’40s and ’50s the British government actively encouraged immigration from Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, Antigua and other West Indian nations to rebuild the UK’s workforce and depleted economy. In that, cities like Birmingham and Manchester and areas of London such as Brixton, Notting Hill and Hackney became some of the UK’s most richly diverse communities.

As an accomplished trumpeter in the ’50s Peter found work alongside fellow Trinidadians Lord Kitchener and Rupert Nurse respectively as calypso began to enjoy success both amongst the West Indian expatriates of London and internationally. At the same time Eldica was earning herself credits as an actress, most notably in the film Cry, The Beloved Country alongside Sidney Poiter.

After Eldica and Peter divorced in the mid-’50s Peter then moved to Germany, and under the name ‘Billy Mo’ adopted a different sound and became a household name. Later, two of Eldica’s three granddaughters would become successful vocalists in their own right. As lovers rock emerged from the streets of mid-’70s south London Sandra Reid found fame throughout the early-’80s with sound-system hits ‘Feel So Good’ and ‘Ooh Boy’, a cover of Rose Royce’s iconic 1977 hit of the same name.

Notably, her stepfather was the lead vocalist in the afro-jazz greats Demon Fuzz, whose 1970’s LP Afreaka! regularly fetches an eye-watering £600+ on Discogs. During the tail end of disco in the late-’70s – when a more distinct calypso-inspired sound of NYC emerged from Europe with the likes of Boney M – another of Eldica’s granddaughters Jayne James became lead vocalist for the band Eruption, featuring on the later releases ‘Baby Don’t Go’ and ‘Brokeaway’ before splitting in 1985.

Her husband was also Martin James, drummer in the 20th Century Steel Band whose ‘Heaven & Hell is on Earth’ has become one of the most sampled tracks of all time. Depending on your era you’ll recognise those first 12 seconds from a seemingly endless stream of modern classics, from Grandmaster Flash ‘Fastest Man Alive’ and Soul II Soul ‘Dance’ to arguably its most widely recognised airing in J Lo’s ‘Jenny from the Block’.

“In the ’70s there were record shops, record labels and great clubs here that a lot of the old people still talk about. Actually, throughout the whole 20th century Dalston has always held musical importance and a rich heritage,” Andy says, describing his homesteads often overlooked musical heritage. Dalston’s reputation as a burgeoning music hub was cemented long before the area was a branded buzzword created by home county estate agents.

Opened in 1966 The Four Aces, arguably Dalston’s most iconic venue, welcomed a who’s who of modern greats in Bob Marley, Jimmy Cliff and Ben E. King during their formative years. By the time Desmond Dekker performed at the Aces in the same week ‘Israelites’ peaked the charts at number 1 in 1969 – the first reggae track ever to do so – Dalston was a hub for Afro-Caribbean music recognised far beyond its Hackney borders. Throughout the ’60s and ’70s further clubs like The Rambling Rose, The Macador and Cubies all became synonymous hotspots for Dalston’s reggae enthusiasts, and for those who couldn’t make it to the clubs homemade sound-systems were back alley dancehalls instead as Afro-Caribbean music took root in east London.

But from the days of Ambrose Adekoya Campbell – the first black artist to ever perform in London in 1945 – to grime and afrobeats today, for as long as black artists have created new music in our capital the police have been quick to clamp down on it as a predictable response. After repeated police raids The Four Aces changed its name and door policy to Labyrinth in the late-’80s, and while that conveniently coincided with the rise of acid-house – seemingly an ‘85% white audience’ on ecstasy was less of a police issue than a Jamaican sound-system – the club closed in 1998 and made way for flats a near-decade later. Cubies, The Rambling Rose, The Macador and many others had already followed suit years before, associated with violent conduct by the police or targeted with yet more raids before the infamous Form 696 somehow made those actions ‘legitimate’.

Yet while these hotbeds of Afro-Caribbean heritage have long since past within the walls of Eldica these clubs are given new lease of life, at least in the memories formed in those places. “People seem to feel at home here and that’s what it’s all about, it’s like an old barber shop,” tells Andy, and that’s true. Almost without fail every time I visit the store, I’ll become locked in a conversation with Jacko, part-time Eldica employee and long-time dance partner of Andy’s, usually about either a) James Brown or b) something that’s confused him that day.

From customers who’ve lost entire collections in marital arguments – one collector came home from a weekend away to find his records tiled floor to ceiling on the bathroom walls, Andy tells me through grinned laughter – to anecdotes from the golden days of British soul with every Eldica patron comes a wealth of experiences. “Customers tell stories about sound-system battles in 1975, hitting people with baseball bats, lifting off a DJ’s record in a clash and ‘this sound was better than that sound’ kind of arguments that make for the funniest, most amazing stories.”

Though gentrification is not individual to east London – Notting Hill is far from than the epicentre of carnival it once was after all – Dalston is arguably almost a parody of its own transformation. But for the decades old locals who still drink at The Kingsland Irish pub or buy their meat from Ridley Road Market the area remains home – and for many Eldica is their intergenerational hangout. “We have everyone from the youngest to the oldest finding and buying records here,” says Andy. “Last month a 14 or 15 year old boy came in, he took hours looking through all the records and he left with a Luther Vandross record. I’m sure that was his first experience of going into a record shop and it was in Eldica. That’s the best feeling in the world.”

“On the other hand we have a regular called Frank who must be about 85 years old, he’s a complete jazz head and he knows absolutely everything,” he goes on to say. “If there’s a Dizzy Gillespie record from 1942 he’ll know every single musician, where it was recorded, the time of the session, everything. We have a lot of women coming in to buy records, old reggae musicians like Eugene Paul who after 50 years of collecting are still finding new records here, and even people who live in Trinidad come here specially to buy their calypso records.”

Over time Eldica has become a ‘hidden gem’ for touring DJs and local names alike. For years Floating Points was a regular every Saturday, and with the NTS Radio studios based just around the corner you’ll more than likely bump into a few hosts throughout the week scrabbling for last minute selections. The likes of Theo Parrish, Throwing Snow, Beautiful Swimmers and Andrew Ashong all make a stop at the store when they’re in town to pose for grainy photos. “It’s basically down to word of mouth, paying a fair price and finding good records,” says Andy, casually.

It’s a disappointing truth that for shops like Eldica, the Caribbean BBQs on Gillett Square or the rare café’s selling fry ups for a fiver, the future remains uncertain. Statistically, Hackney itself is dramatically improving. Poverty has shrunk from 42% in 2010 to 17% in 2015, and crime has fallen by over a third since 2003. However, over the past decade those who rent from a private landlord has doubled, and as the population is set to increase 300,000 by 2027 many of these improvements aren’t necessarily benefiting Hackney’s decades old communities.

Eldica is not going anywhere fast but for others like Stoke Newington’s Lucky Seven, who may be forced to close later this year due to increasing rent, they may not be so lucky. “Artists, students and the so-called ‘hipster’ have been moving in and out of the area for years, and that’s cool,” says Andy. “But when the new wave arrives, which will be the bankers, that’s when it’ll die and that won’t be a nice place for anybody.” Until then, enjoy Eldica for what it is; a taste of the old school for those bored of the new.

Photography by Michael Wilkin