In just a few years, DJ, producer, promoter and activist Julianna has founded a record shop, set up club nights and record labels, released her own music, and co-founded NÓTT, a feminist techno collective which connects with artists across Latin America. Holly Dicker traces Julianna’s musical journey, from her mother’s disco records to championing Colombian electronic music around the world.

Juliana Cuervo aka Julianna is one of the most vital figures in Colombia’s bubbling techno scene. As well as Move, one of the best underground dance music events (and now a record label) in her hometown Medellín, she’s an active member of NÓTT, a platform much like female:pressure, which focusses on supporting women and transwomen in the Latin American electronic music community.

Although also a producer – “soundscapes for exhibitions, mostly” – Julianna’s true passion is for DJing. She honed her craft as resident at Mansion, a much-loved venue in the city that closed in 2018, playing Buddhist mantras and whale songs during opening sets, and freestyle – a Medellín favourite – when closing.

With music-obsessed parents and uncles in one of the most prestigious orchestras in Medellín, you could say a career in music was inevitable for Julianna. Except, despite an early orientation towards raving in her “difficult” teens, she chose to study animation film in Buenos Aires instead – a time that proved formative for Julianna’s musical development, collecting records and discovering music she couldn’t find in Colombia at the time.

An illustrator by trade, Julianna has started touring through Europe in recent years, an experience she’s humbled by. “I have this chance to come here,” she says from Berlin during a stopover between gigs at Tresor, Industria Club in Porto and an all night takeover at Stardust Madrid. “But as a Latina, it’s a privilege. It’s not easy for an artist from this part of the world to do this.” So, whenever she plays for foreign dance floors, it’s always with Colombia in her heart and shining through her track selections.

Having recently helmed the Colombian iteration of place – a country-specific electronic music compilation, with proceeds donated to local human rights group Mutante – we spoke to Julianna to connect the many threads that have led her to playing such a prominent role in Colombian electronic music.

When did you start collecting records?

I started in 2010 when I used to live in Buenos Aires. At the time, there were more record shops in Buenos Aires than Colombia. I was a DJ as well, but when I left Medellín I decided to focus on my studies.

Were you going out in Buenos Aires too? What was the club scene like back then?

It was very strong. I met Appleblim, because I used to go to UK bass parties, and techno names like Mike Parker and Rrose. I was going to Cocoliche, which was the best [place] at that time, and a party called BULLYBASS, which was dubstep.

So you didn’t start playing or collecting techno then?

I started with IDM and Chicago house. It was James Holden who introduced me to the music I was into, but mixing Border Community records was so hard as a beginner. I only got into techno when I moved to Buenos Aires and discovered deeper artists like Mike Parker. I didn’t have the chance to discover these kinds of artists in Colombia at that time, so it opened my mind to different music.

What was the first record you ever bought?

Lords of Acid’s ‘I Must Increase My Bust’. I found it in a tiny record shop in Corrientes Avenue, managed by a very old man. He had got some records from Frankie Knuckles, which were super expensive. I was attracted to the name of the record and the sleeve, but I have never played it. I still have it because it reminds me of when I started to buy music.

As an illustrator, does sleeve artwork play a big role when you browse for records?

Definitely. I like to buy records that also look good. Often, if I don’t know what the record is, I buy it because I like the sleeve. It’s a nice way to share an idea of what music is.

What’s this Hello Kitty record about?

That’s my first record! That was a joke, actually. That was the record my mum used to play to me when I was a child. I have it because my parents moved recently and she gave it to me. We used to play that all the time.

So your parents are record collectors too?

They listen to and collect mainly salsa records and bolero, which is a very Latino music. I still listen to that kind of music at home.

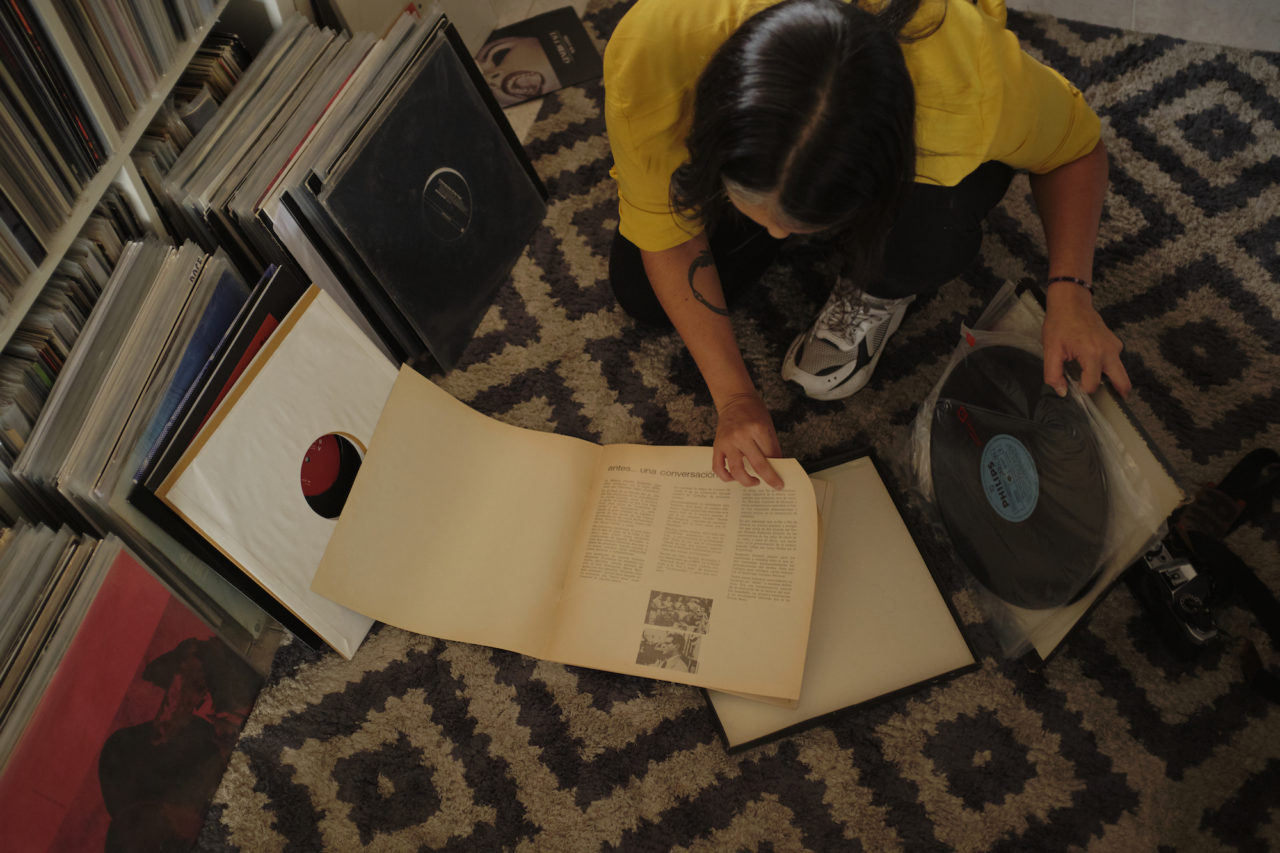

Did you inherit this bossa nova compilation from your parents as well?

I bought that in Buenos Aires. It’s a nice compilation of records. I was very attracted to the box. I knew bossa nova would be nice to listen to, but I was interested in not only the sleeve but also the inserts, which tell the story of the composers and the music.

What made you decide to return to Medellín?

After five years in Buenos Aires, I decided to come back because of the socio-economic situation in Argentina. I also wanted to keep DJing, and I couldn’t play in Buenos Aires. It’s a very closed circle, and as a woman it was much harder back then. I didn’t have the right connections to start playing there, so I decided to move back to Colombia and start my own parties with some other friends.

Was this the beginning of Move?

Yes. We decided to unite as different DJs and start this collective, throwing parties in places other than clubs – building our own club for a night in warehouses or bunkers – and bringing music to Medellín that was hard to find at that time. We opened a door to different music in our city. We brought DJ Stingray, DVS1. It became like a family. We started a record label last year, too. The first release is an EP featuring residents.

You’ve also started a label with NÓTT. How did you put the 2019 Austral compilation together?

We started to write to women interested in our project, using our database. We did an open call and they gave us these 14 tracks. It has been good to see what women are doing in other parts of the continent, in Peru, Chile, Argentina, Brazil, and Colombia, of course. I have a track in the compilation, but I think I’m not very good at making music for clubs. I consider myself more of a DJ than producer, and I like that.

Where did the idea for NÓTT come from?

Marea [Arango], Andrea [Arias] and I decided to join forces three years ago and start a database for women, because promoters were saying that there weren’t women DJs in Colombia. Now we have a big network of women in Latin America. We try to make women in electronic music more visible – not only DJs. We realised that a lot of women wanted to be DJs, but were afraid to learn the techniques. This is part of a social behaviour in Latin America; the idea of the “macho” and women staying at home. We run workshops teaching Ableton live, DIY oscillators, DJing with vinyl, DJing with CDJs. We also do showcases in different parts of Colombia. We have a podcast series and a radio residency, which is like an open door for different women and transwomen in Latin America to show their mixes.

Speaking of radio, I notice you have a Red Light Radio slip mats – is that from the closing party of your record shop Doce?

Yes. It was a really special way to close the record store. It was the first time Red Light Radio came to Colombia. This idea to share local music has always been very gratifying for me, so I’m really grateful to them. I like to play music from my region. I always play music from Latin artists in my DJ sets, and buy music and support local scenes.

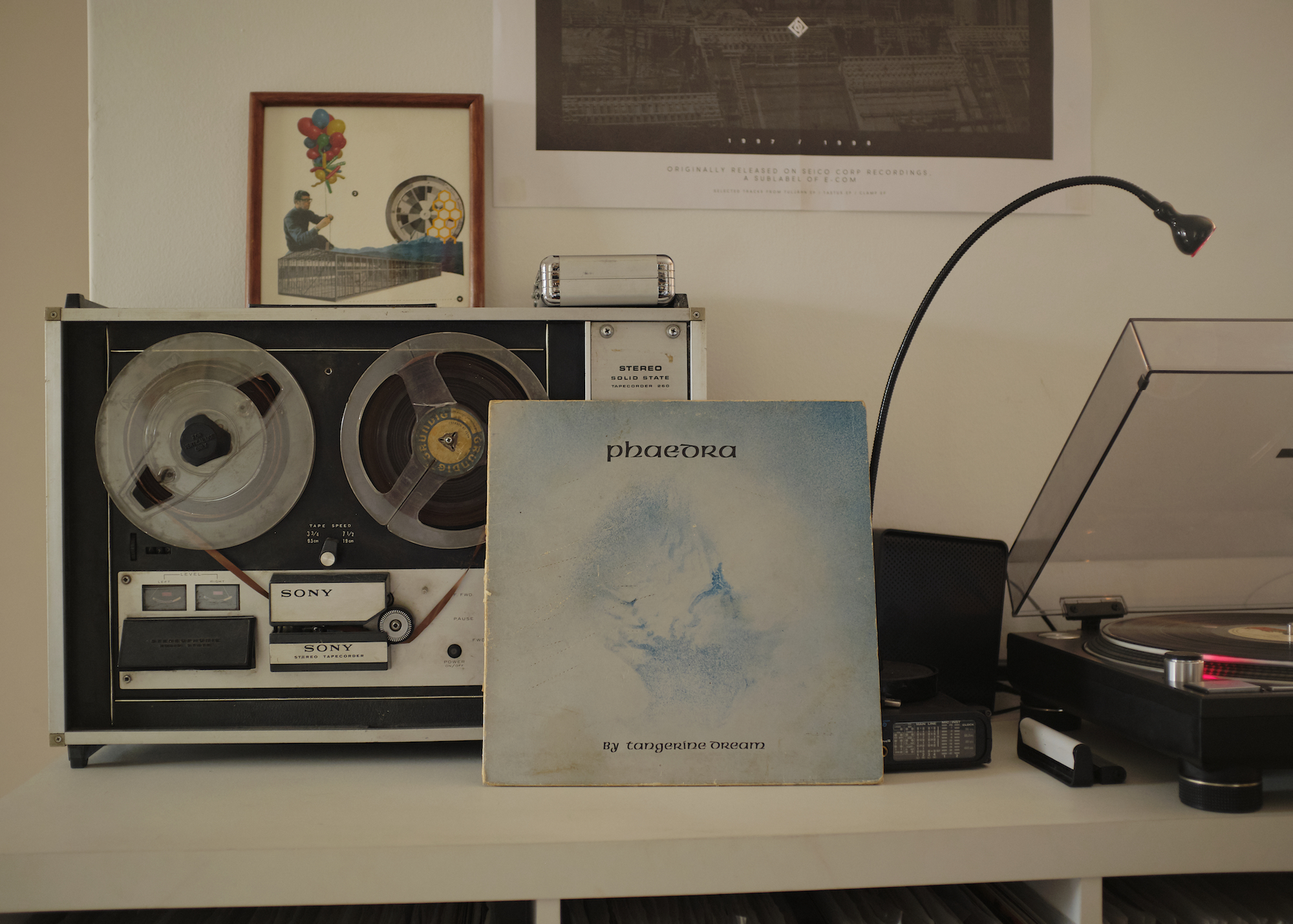

This seems like a good moment to talk about Medellín Rave Society EP and Wire 00 – I love Wire’s music from Mord.

Medellín Rave Society is the first various artists EP from Insurgentes, a label run by Verraco and Defuse, and Wire is my partner Santiago [Merino]. I support him a lot because he makes amazing music. Merino is his main alias, and he has a track in this Medellín Rave Society EP. Insurgentes has been getting a lot of attention recently and it was important for us to have a record with the name of the city presenting great producers with a different approach to techno. It’s so beautiful and well done.

Wire started as an experiment and this first record was made independently. Santiago started with a CD and put it on Bandcamp. Bas Mooy [from Mord] then found it and asked for more music. I always play his music everywhere.

Why did you and Santiago decide to open a record shop in Medellín? Was it harder than you anticipated?

We started because we always loved to play with vinyl. We thought it would be easier to bring music to Colombia because there was this bubble of vinyl DJs. But we closed two years ago. It was hard. We had to import all the records. The euro is four times the Colombian peso and we had to pay a lot of taxes, so we had to add all this to the price of the vinyl. To be honest, in Colombia we don’t have a proper culture of buying music and vinyl is a luxury item.

Do you have any vintage Colombian records in your collection?

From my mum. She gave me her record collection, including this House On Fire compilation. Discos Philips was one of the biggest record labels in Colombia. They released pop music in the ’80s. This industry collapsed and died with digitisation. The last vinyl pressed by Discos Philips was completely forgotten in a warehouse. When we started Doce, people were like, is vinyl not dead?

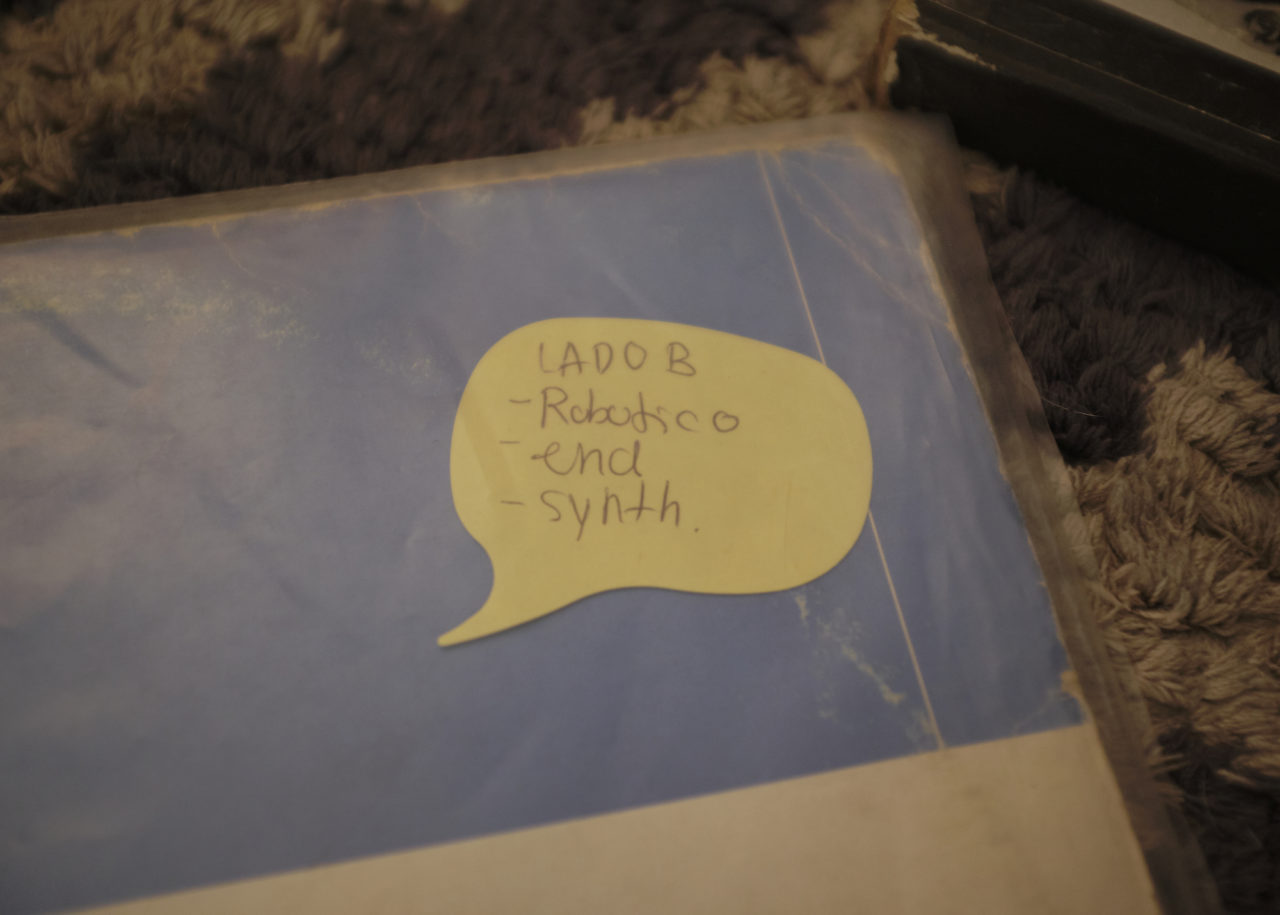

Tell us about the freestyle records in your collection.

Freestyle is very important for Medellín. By the end of the ’90s, Colombia was well recognised for narco trafficking. Towards the end of the ’80s and early ’90s, freestyle was the kind of music narcos brought back to Colombia from the US. It was so popular to listen to freestyle in Medellín.

That’s why we have the connection with the 808 and this electro sound. Today there is a small freestyle scene, but it’s mostly older people from that generation. I used to be resident in a small club called Mansion. When you play regularly, you have to have a fresh selection for different set times. I always play these records when I close the party because people are super happy. I bought this kind of music with the idea to experiment on the dance floor.

Where did your passion for disco come from?

That’s also from my mum and her record collection. I would not listen to this kind of music if it wasn’t for her. My mum had records from Donna Summer, ABBA, these weird house compilations. Plus lots of salsa records. I know a lot about salsa music because I grew up with it. It’s weird to end up playing techno and house, but I think the rhythmic patterns provide a connection between the two worlds.

Photos by Jack Dizz.