Crate Diggers: John Gómez

The DJ and collector behind Music From Memory’s boundary-pushing Outro Tempo compilations, John Gómez has been instrumental in bringing Brazil’s experimental and electronic music to the fore. With the second collection out now, he spoke to us about dance floor epiphanies, pushing beyond MPB, and the ethical concerns of contemporary reissues.

In the liner notes to Outro Tempo II, John Gómez tells the story of how Yugoslavian producer Mitar Subotić – or Suba – helped change the direction of Brazil’s dominant popular music, MPB. “He was a seasoned producer who brought with him an unprecedented technical sophistication and a unique sensibility. He offered an uninhibited vision of Brazilian music that was not limited by cultural constraints.” His contribution to the best-selling Brazilian album of all time, Bebel Gilberto’s Tanto Tempo, was, in Gómez’s words “the result of an outsider’s thrilling vision of Brazil being absorbed into its soul.”

Having lived a life between Madrid and London, the perspective of the outsider has played a role in Gómez’s own musical life, whether as a DJ or in an academic context, drawing him to sounds that fall between genres.

On Outro Tempo II, Gómez employs that perspective to shine light on a previously overlooked area of Brazilian music – one where the postcard stereotypes evoked by bossa and boogie are replaced by a more complex, electronic vision of the country’s musical heritage. The world Gómez presents is one of brooding synths, dextrous poly-rhythms, and angular vocals – a radical sound born out of post-dictatorship Brazil, that has, in the current political climate, taken on a greater resonance.

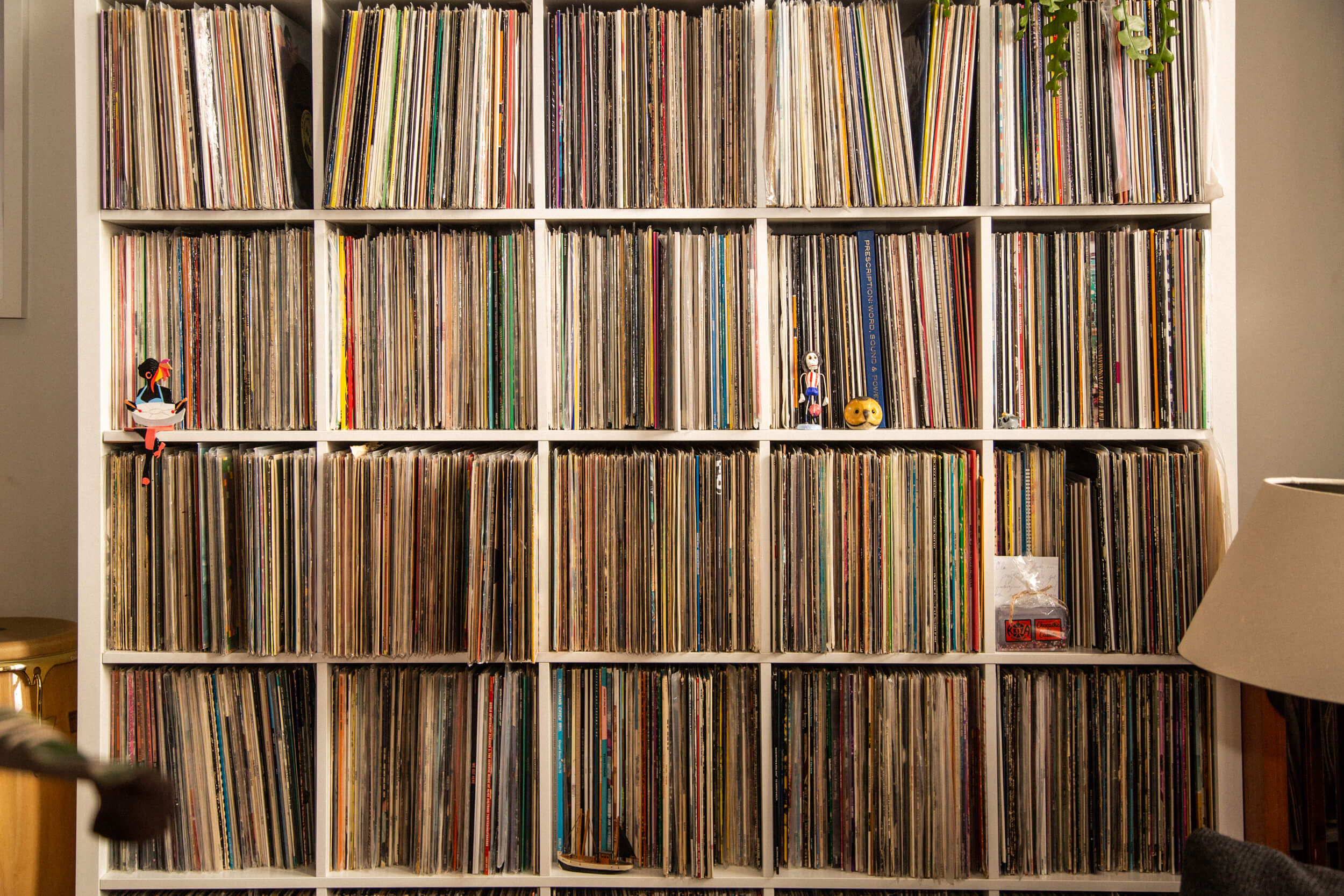

Currently based in London, Gómez’s collection spans a journey in music from hip-hop and jazz to the furthest reaches of the Discogs multiverse, and over the course of the interview, he points us to several ‘ghost’ records in his collection – those with little or no online trace.

On the heels of Outro Tempo II, John Gómez follows the thread from teenage appreciation of George Duke’s A Brazilian Love Affair, to finding his own place as an outsider contributing to the country’s multi-faceted musical history.

Growing up in Madrid, and now living in London, you’ve described yourself as being drawn to music that comes from the spaces in between.

Having an English mum and a Spanish dad has meant always living in that space between two separate cultural identities and I think it has shaped how I listen to things. My background is in hip-hop, but I also studied music, the trombone, jazz, and later drums and Latin percussion.

Things started to get exciting for me when I started finding musicians that were bringing together hip-hop and jazz, such as Digable Planets or Guru and his Jazzmatazz project. That combination of different elements that don’t sit quite in one or the other category is what I’ve always found most exciting and vibrant.

Do you find that people expect something specific when they book you as a DJ?

I think I’m lucky in that I get booked to play in very different contexts. Although I am generalising, if you’re a strict techno DJ you’re mainly going to be booked to play late nights in clubs, right? Luckily I get to really stretch my record collection with different bookings, from daytime parties where organic sounds might be better suited to dark clubs where I can play deep, cosmic sets.

It sounds like you get a different kind of satisfaction from each of these scenarios?

Yeah I really love it. Especially the late sets as after a certain threshold in the night, you usually get to take more risks. It’s also at those times that I’ve had my own epiphanies on dance floors.

Can you put your finger on some of those epiphanies?

If I’ve had an intense experience with a record that someone else has been playing, I’m quite mindful of trying to recreate that experience. I was thinking about this recently when Mark Hollis died. I used to go to the World Unknown parties in Brixton. There was one party that I remember in which Andy Blake played Talk Talk’s, ‘Life is What you Make It’ at about 5am. It was a perfect moment and was genuinely one of the most intense club experiences I’ve ever had. But I’ve never been able to play that tune in a club, as I’ve never been able to get to that point where it would make sense in the same way. I think there’s a very particular journey that you need to go on to get to some records.

Could you tell us about one of your journeys?

When Nick [The Record] and I play our Tangent party, musically we go everywhere over the course of seven hours, building slowly. We want to reach a point in the evening when we can plays these deep records. I’m really into these heavy percussion records that change the dynamic from a strict 4×4. They work really well on a dance floor, but you can’t just throw them in as your first record. It’s almost like you’ve got to earn your right to play them and make sure that the time is right. Things like Julien Babinga’s M’Bongui-Percussions or Conjunto Baluartes’ Nira Gongo, which almost sounds like a lost Arthur Russell Brazilian collaboration with those ghostly voices.

When did you begin to play records?

As a teenager, but it was always as a hobby, something I did for fun. I bought some really cheap belt drive turntables with a Gemini scratch mixer when I was 15.

In Madrid, there is a gap between small bars and big clubs that is lacking even to this day, so I grew up playing in bars and at home parties. The idea of playing in clubs was not accessible to me until the last ten years or so, as the club scene has changed a lot and is much more receptive to sounds that at another time would have been impossible to play in a club setting.

It feels like dance floors have been open to increasingly obscure music in recent years. Has the quest for rarity and the effect of Discogs also played a role?

People are listening to so much music now and I’m astonished by the amount of information that 25-year-old DJs have. When I was a 25, I had a feeling that I was on top of it, knew quite a bit, but it’s just a different level right now.

The flip side to this is that I think that resources like Discogs change the way we value music. When you have statistics in front of you relating to price and how many people are looking for a record, I think it affects the way we hear things, as we can be fooled into believing that something isn’t good simply because it is not valued within a record community.

I think it’s very easy now to follow what the rare records are by what people are playing in mixes and posting on YouTube. People aren’t necessarily listening with their ears though, and too much value is placed on rarity and demand. I think a lot of people are missing the building blocks and are skipping straight to what is valuable online, or to what is perceived as valuable because it has been playlisted by a particular DJ.

Maybe it also makes it harder to be confident in ones own taste? Gravitating towards certain records or sounds can help make sense of the vast quantity of what’s on offer, with the result that people actually end up having quite similar tastes.

I rarely listen to mixes because of that. It can start breeding a sense of insecurity. I have reached a point now in which I really believe in my records and in what they can do, but that takes time. Ultimately, it’s not just about the records that you play. The way Antal plays, the way Hunee plays, the way Jamie Tiller and Orpheu play… although there will always be some overlap that reflects trends, everyone has a distinct personality.

You mentioned your relationship with your records. Do you feel like this collection is a fairly accurate representation of your journey through music?

Yeah, for sure. I’ve also got a lot of records in Madrid at my mum’s house. A lot of those early hip-hop records and a lot of my jazz, soul and Latin records are in Madrid, which reflects what I was listening to when I was living in Spain.

Do you feel comfortable giving records away?

Yeah, I need to, because things have to have some sort of function. Every used record I pick up is something that someone else has discarded, so I think it’s fair to say that something I might not be interested in might actually be valuable or precious to someone else.

Some people value the idea of having an artist’s full discography. It doesn’t like that interests you?

I’m not a completist at all. I’ve never attempted to complete any particular discography. I was, however, very happy to bring together one of my favourite Brazilian LPs João Donato’s Quem É Quem with the album’s two 45s.

Are there other specific records that made you fall in love with Brazilian music?

George Duke’s A Brazilian Love Affair is one of those records that was super influential for me, acting as a gateway for me into Brazilian music. I remember getting it when I was about 19, unaware of how big this record had been on the London rare groove scene. It was played by broken beat DJs in London and house DJs in New York. It’s a record that brings together all my interests. It’s pretty obvious and pretty literal, but this definitely started my own Brazilian love affair.

What kind of things do you look for in a record when you’re out digging now?

I look for something uneven or unusual. So it could be a standard looking jazz record in which I notice a drum machine listed in the credits. This makes me think, “OK, there’s something on this that could be a little bit interesting.” It’s those little inconsistencies that make a record stand out for me.

Is that mentality something that informed the Outro Tempo compilations? A lot of the instrumentation there seems quite unusual.

I think initially, yes. I found the Maria Rita record in Japan and thought the graphics looked amazing. Then you open it up and it looks like this DIY thing. Even the typography is unlike anything I’d ever seen from Brazil. That really made me interested in it.

So that was the gate way record into this world? It feels like you pulled on a thread and a lot more unravelled…

A whole world opened up that I didn’t know was there and, perhaps more importantly, it was a world that it seemed nobody had thought about piecing together. I just saw an opening and a narrative. Until that point, the focus from outside on Brazilian music had been limited to certain genres and had conformed, to a degree, to stereotypical images of Brazil. It was exciting to be able to help showcase that there was this darker, more experimental side to the country, a side which had produced some truly fascinating music. People are now pulling a similar thread in other countries in South America, exploring the music of places like Uruguay.

For me, a compilation can have the potential to shape and change a narrative.

For me too. As a compilation producer, I think it is always important to ask what is the story informing the music and what is the personal connection I have to it. In the case of both Outro Tempo, compilations I was obviously a foreign observer, but this position gave me a lot of freedom. In this sense there are parallels with the music that Yugoslavian producer Mitar Subotić recorded in Brazil, which I collected in Outro Tempo II.

Suba’s arrival in São Paulo and his collaborations with Brazilian musicians had a dramatic impact on the local music scene. He brought something completely unique and fresh to Brazilian music, as he wasn’t weighed down by the feeling of having to do things in a particular way. He was not from that world and was able to listen with a different ear, which in turn led the music to unexpected and exciting places.

The liner notes suggest you are particularly conscious of your own position in relation to the music.

When we did the live show of Outro Tempo in São Paulo in 2017, my friend and producer Kassin insisted that I introduce the show in English. Besides my terrible Portuguese accent, he said that it’s “important for people to realise that we’ve had this music here forever and we haven’t valued it until someone came from outside.” I’ve got mixed feelings about this, as it depicts the person from outside as some sort of saviour. It’s not like that at all; all of the music I have worked with had had a meaningful life before I came across it, but in a different context to ours. I think that having someone from outside re-packaging one’s culture has an uncomfortable echo of colonialism. It’s really tricky, but I think that these are important questions to confront when engaging in this type of project. But as long as you’re respectful and working within the culture in a collaborative way and not hierarchically, then I think it can be balanced and meaningful.

The second compilation has a slightly different feel to the first. Was that intentional?

It was important for me to do something different. I hadn’t really thought about doing another comp, and I needed to get some distance from the first project. It wasn’t until I started listening to other music that I began to see another narrative emerging. Rather than simply taking the outtakes from the first one it needed to feel like an evolution. It is darker and slightly more electronic. I don’t know if it will be for everyone, but for me I think I had a responsibility to do something that felt creatively as risky as the first.

What is the narrative for you?

If we’re talking again about that space in-between, these years represent a transition in which a new energy emerged in Brazil. The first comp looked at the slow transition towards democracy that started towards the late ’70s, as the military regime was beginning to soften. Here, on this second collection, there is more of a feeling of liberation. It’s almost like São Paolo went out on a big bender and a generation of young middle-class musicians that had come of age during the dictatorship years decided to break with what had come before. Following a period of significant social and cultural oppression, the period saw a new wave of experimentalism and collective mobilisation around new ideas that were reaching Brazil through the ever rising forces of globalisation and consumerism.

This generation of musicians no longer related to the big stars of MPB (Música Popular Brasileira) as they had been absorbed by the industry and their music had become the officially validated soundtrack to the opening after the dictatorship. By this point in Brazil’s history, the musicians that had once been the voices of protest were doing huge televised performances. The musicians on Outro Tempo II turned their back on this culture to offer up a new music of dissent that would rethink the idea of MPB and move it into a new era.

There’s also a slightly different Brazil now to the one into which the first compilation was released.

I was working on this in the lead up to the elections, and when Bolsonaro got elected I had mixed feelings about putting the compilation out, as I wasn’t sure there was anything to celebrate. But now I think that its darkness resonates with the current political situation, and I’m glad that it shows that things are not perfect. It feels more honest and I think the compilation can help remind people of the darkness they’ve been through already. If we see Brazil only in terms of beaches and parties, we experience the country as a lie. Behind the postcard image are decades of social, political, and economic injustices and I hope my compilation helps present a more complicated version of Brazil that takes these aspects of the country into account.

John Gómez and Nick the Record’s Tangent takes place this Friday 12th July at Pickle Factory in London.

Photos by Ceili McGeever