Composition as Collaboration: A journey through Björk’s career

Alex Ross narrates Björk’s career through her collaborations.

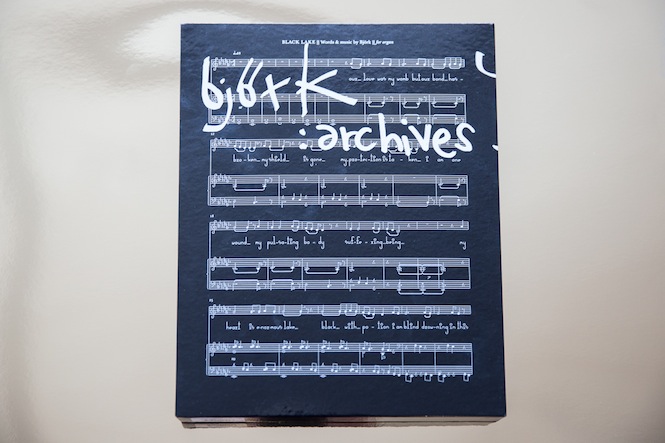

With the vinyl release of Vulnicura on its way, not to mention a colourful back-catalogue reissue and a mid-career retrospective at MoMa, we take this opportunity to reflect on the musicology of Björk.

The edited extract below is taken from Alex Ross’ essay in the incredible five part box set publication “Björk: Archives“, published recently to accompany the MoMa exhibition.

Words: Alex Ross

Björk resists being called a composer, even if she has drawn extensively on the notational classical tradition. The cult of the solitary genius is alien to her. Instead, she sees her work as an essentially collaborative enterprise, one that calls for an entire community of musicians, studio technicians, instrument-makers, producers, programmers, videographers, fashion designers, and other creative individuals. She is not the kind of pop star who makes a game of donning masks and disguises; her vocal identity has changed remarkably little over two decades as a solo artist. But almost everything else has changed: the instrumentation, the arrangements, the production techniques. Her albums tend to react against one another, with extroverted moods giving way to intimacies, dense textures followed by transparent ones.

To a great extent, Björk’s career can be narrated in terms of her collaborations. In the early and mid-1990s, she was living in London, keeping close tabs on the city’s club scene and maintaining a hectic nocturnal schedule. Debut and Post were in a way, portraits of a multiculturally swinging city, with purring trip-hop beats layered beneath the sinuous strings of Talvin Singh and more opulent parts that Björk co-arranged with Eumir Deodato.

Synthesized sounds met up with the tootling and plucking of a community band or orchestra: flute, harp, accordion, harmonium. The tone of these first albums is caught by the title of a song toward the end of Debut: “Violently Happy.”

Homogenic, from 1997, marked the end of Björk’s London phase; she moved back to Reykjavik the following year. The producer Mark Bell became a crucial member of Björk’s team, injecting cooler, more brittle timbres. The Icelandic landscape can be sensed in the volcanic spasms of songs like “Pluto,” or in the pummelling rhythms of “Hunter,” which suggest a terrain being trampled by hooves. At the same time the record suggests a turning inward. In the song “Jóga,” Björk sings of “emotional landscapes,” of a “state of emergency.” This exploration of a sometimes inviting, sometimes forbidding inner geography goes even deeper in Vespertine, which appeared in 2001.

Here, Björk’s collaborators, apart from Bell, included the producer-songwriter Guy Sigsworth, the electronic musician Matthew Herbert, the avant-garde harpist Zeena Parkins, and Drew Daniel and M.C. Schmidt, of the electronic duo Matmos. Yet the glistening, twitchily sensual musical fabric of the album, which includes parts for glockenspiel, celesta, and music boxes, was largely Björk’s creation, with most of the beats created on her laptop and musical parts written in the Sibelius composition program.

In 2004, I had the opportunity to watch the making of Björk’s fifth solo record, Medúlla, and could see first hand how her music gestates in a matrix of creative exchanges. The recording process took Björk from the Canary Islands to Iceland and on to Salvador, Brazil and London, where the final mix was done. Partly in homage to Meredith Monk, Björk set out to demonstrate the myriad textures, from the ethereal to the percussive, that can emanate from the human voice: solitary folkish song, choral swells, breathy feminine whispers, raw heavy-metal shouts, beatboxing, and various other techniques. The avant-garde rock vocalist Mike Patton, the Inuit throat-singer Tagaq, and the “human beatboxes” Dokaka and Rahzel joined the ever-expanding, ever-changing Björk community; unfortunately, plans to add the R&B superstar Beyoncé to the mix ran up against logistical difficulties. Given the meandering itinerary of the creative process, it was striking how cohesive the album turned out to be: working in conjunction with the recording engineer Valgeir Sigurosson and the mixing engineer Spike Stent, Björk shaped disparate material into a potent whole.

Three years later, with Volta, Björk again reversed course and reclaimed the extroverted mood of her early albums, although she kept hold of the more adventurous resources that she had been deploying since Homogenic. This partly tended toward the darkly chaotic. The hip-hop producer Timbaland added tribalistic beats that happened to resemble Afro-Brazilian drumming tracks that Björk had recorded for Medúlla and then set aside, sensing that they didn’t fit that album’s tone. An all-female, ten-piece brass ensemble provided glowering bass sonorities. The indie soul singer Antony Hegarty sang duets with Björk on several tracks, establishing a contrasting mood of sensuous otherworldliness. If the record lacked the thematic united of Vespertine and Medúlla, it again demonstrated Björk’s knack for disrupting the pop consensus.

Biophilia in 2011, is perhaps Björk’s most ambitious project to date. Part album, part stage spectacle, part iPad app emporium, part new-instrument laboratory, and part grade-school curriculum, it is almost Stockhausenlike in its joyous disregard for the constraints of genre. As often before, Björk set about mapping the intersection of art, nature, and technology, presenting analogies between scientific and musical elements. “Crystalline” compares crystal structures to the efflorescence of songs from small motifs; “Solstice” likens swinging pendulums to overlapping contrapuntal lines; and “Virus,” whose folklike melody seems to come from the depths of the centuries, has an unstable, ever-shifting accompaniment that suggests cells subdividing and multiplying. The battery of bespoke instruments include the gameleste, a MIDI-controlled device that incorporates gamelan-like bronze bars in a celeste housing; and the Sharpsichord, a forty-six string automatic harp controlled by a pin cylinder.

In the wake of the cosmic effort of Biophilia, another change of course seems inevitable. Lately, with an eye toward a new album, Björk has been recording more intimate confessional songs with strings. There is no doubt that these records not only document an intellectual journey but also a personal, psychological one. How the work matches up with the life is a subject on which only the artist herself can speak, and the biographical details are, in any case, somewhat immaterial; what counts is the sense that each song is an attempt to transmit honestly and unabashedly an inward state, rather than to concoct a calculated, knowing image for the outside world.

Björk: Archives, with contributions from Klaus Biesenbach, Alex Ross, Nicola Dibben, Timothy Morton and Sjón, published by Thames & Hudson on 2nd March at £40.’