Celebrate Ornette Coleman: Artists pay homage to the legendary avant-garde saxophonist

Two years since his passing, one of Ornette Coleman’s dear friends Vivien Goldman remembers his legacy with help from Thurston Moore, Laurie Anderson, Flea and those closest to him.

A lavish new box set of two events filmed one year apart, Celebrate Ornette honours the last steps of the extraordinary musical journey undertaken by the late Ornette Coleman. The dovetailing of these two events is both wrenching and glorious. Gathered here are the Celebrate Ornette concert held on a balmy June evening in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park on 12th June, 2014, featuring close artists playing his music. Among them were Patti Smith, pianist Geri Allen, guitarists James “Blood” Ulmer, and Thurston Moore, saxmen David Murray, Branford Marsalis and Joe Lovado and synthesizer innovator Laurie Anderson. Patti dropped a kiss on the Master’s head before going onstage. Ornette himself made a surprise appearance to blow his unmistakable horn – his final time on stage. And then, almost a year later, on June 25, 2016, came the visionary’s Memorial service, held at the grand old Riverside Church in Harlem.

This potentially somber successor was made joyous by loving spoken tributes and stunning versions of Ornette music. Players including Ravi Coltrane (Ornette had played at his father John’s funeral in 1967,) and pianist Cecil Taylor brought home how profoundly inspirational an artist Coleman was – and always will be. The literal magnificence of the music injected life even into Ornette’s passing. The vivid, untempered skirls of his old friends, Morocco’s Master Musicians of Jajouka – a sound traditionally used to heal trauma and madness – preceded the coffin. After touching eloquence from speakers including Yoko Ono, poet Felipe Luciano, and sculptor Melvin Edwards, who evoked their connection as “The Texas Boys,” Ornette departed the church to the happy clangour of the Prime Time band playing ‘Dancing In Your Head,’ from Ornette’s mid-70’s jazz-punk-funk period.

Both gatherings were peopled by Ornette’s eclectic extended tribe: fresh combinations like Henry Threadgill and saxophonist David Murray playing with the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ bassist, Flea; Branford Marsalis with Bruce Hornsby performing ‘Questions and Answers’; and the Ornette Reverb Quartet, featuring Laurie Anderson on violin, saxman John Zorn, bassist Bill Laswell, with Stewart Hurwood on reverb, exploring abstract sound; the Patti Smith Group storming through ‘Tarkovsky’ and Thurston Moore’s 2-guitar reverb-drenched take on ‘Sadness.’ Songs range from the iconic ‘Lonely Woman,’ to the unknown: ‘9/11,’ that Ornette composed in the tragedy’s memory. Familiar or rare, the music was never more exquisite than here, as players poured their essence into their instruments to honour their friend and mentor.

As she was leaving after the show, Laurie Anderson stopped to say, “Ornette is colossal for me. He can swim so far out, further out that any musician I know – and that is where I want to go. It’s like Lou Reed used to say – I want to play guitar like Ornette plays violin.” Saxman Branford Marsalis tunes into the ground beneath harmolodic’s shoot for the stars: “No matter how avant-garde the music seems, Ornette would get to a place where he would play a phrase, and you would be back in Mississippi and Louisiana. To me, that was the goal, that was the magic.”

Of this crew uniting seemingly disparate artists, Denardo says, “My father was just such a force and affected so many people in so many different ways… he had a huge impact and that community still exists.”

Musician, educator and arranger Karl Berger and his singer wife, Ingrid, were encouraged to move to America from Europe by Ornette, and he helped them found their Creative Music Studio in Woodstock, New York. Berger’s insight underscored their friendship. “Ornette used to say, ‘The less you think, the more your emotions will be fulfilled.’ He had a way with words like no-one I knew… it was just mindblowing,” recalled Berger. “That was almost the point of it. He wanted you to go beyond simple logic when you talked to him. He would always push you beyond thinking to that same intuitive space where he seemed to reside all the time.”

Box sets are a staple, the added value of rare archive photos and essays a lure to download-only millennials as much as committed fans. Indeed, this collection boasts moving essays by family and friends; but what sets this set apart is the extraordinary intimacy of the musical communions it presents.

Celebrate Ornette could only have been put together by people who truly inhabited Ornette’s sphere – in this case, Denardo. They shared an unusual closeness. In 1966, when he was 10 years old, Ornette introduced his son’s drumming on ‘The Empty Foxhole.’ With his flexible, crisp technique, Denardo continued to drum with his dad – and went on to also become his manager. Much of the music here is backed by Denardo’s Vibe, a new combo of players steeped in harmolodics. The set also launches Denardo’s new label, Song X, named after one of Coleman’s own favourite pieces, a 1985 collaboration with guitarist Pat Metheny.

Says Denardo, “It turned out that the last year of Ornette’s life was a one-year celebration bringing all these people together. The box set just worked out that way, meaning, we had the Brooklyn tribute concert and then, a year later almost to the day, he passed away. Once we had the Memorial that turned into a huge concert as well, it made sense to put both them together. They were both historic musical events.”

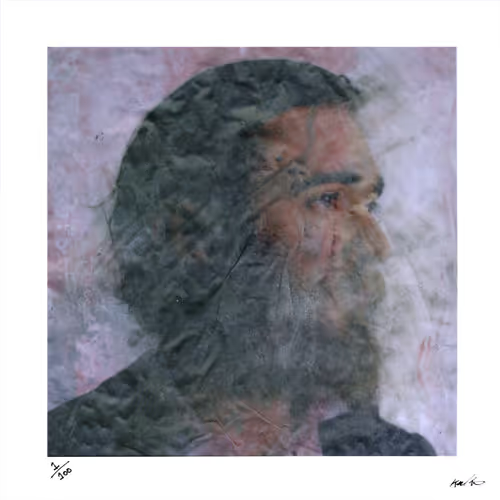

The box set is rich in Ornette’s personal history, with intimate observations from the family, rare images to blow Ornette fiends’ minds. Taken from the archive of his sister, Trudy Coleman (herself a recorded singer,) dig the 1950s teenager with conked hair, already rocking a snazzy suit – ever dapper, Ornette would grow up to wear his own designs. More unseen shots, by veteran Italian jazz photographer Elena Carminati, capture him beaming, totally relaxed, sprawled on the floor of a theatre stage after a set, signing autographs for the fans crowding up to the front.

Born in segregated 1930s Texas, he had to leave to fulfill the vision that drove him, as sculptor Mel Edwards recalls here. First, Coleman settled in Los Angeles, where he became a leader of the bohemian set and met lifelong collaborator, trumpeter Don Cherry; and married his first and only wife, the activist/poet/musician Jayne Cortez, Denardo’s mother. She would go on to wed again – his fellow Texas Boy, Mel Edwards. The next move was to New York, where Coleman’s open spirit helped to create the fabled 1960s loft jazz scene with his Artists House on Prince Street – “When Soho was Soho,” as a friend quips in the film. Wherever he went, throughout his life, Ornette brought an inclusionary creative scene.

Knowing Coleman was a lesson in the humility and generosity of true greatness. His real warmth and kindness built the extended family that we meet on this Set, many of whom have stuck together since the 1960s, with new generations often joining the fold; as with Geri Allen, whose 18-year old son, Warren, had been invited to play with the band for the first time, that night in the park. Ornette was an artistic father figure to many. Said Thurston Moore, “Nobody plays music like him because there’s only one Ornette; and there’s very few musicians where you can say, there’s only one of them.” Flea’s muscular bass suits the headlong rush of harmolodics. He notes: “Someone like Ornette, Fela or Charlie Parker, when you create a new sound like that, pushing the envelope – that music will last forever. The sound and feeling goes beyond the sum of the notes; it is tapping the source.” Confirms bass player, Tony Falanga, “He really went right to the core of the note, how deep, how ancient is that note or tone that you’re playing. Ornette is a natural genius and he was put on the planet for that reason.”

Summing up the deep connectivity and longevity of this somewhat motley posse, Denardo concludes, “They feel they might play a different music, but it’s the same sort of fight for individualism and freedom and non- conventionality. Not having to accept the status quo and not wanting to. It’s not that you’re trying to be an outsider, but you have no problem being an outsider and you understand what that is.”

There are no deeper words to heed than Ornette’s farewell to his final live audience, his philosophy in life as in music: “We can’t be against each other; we’ve got to get together and help each other.”

The Celebrate Ornette box set is out now. Click here for more info.