Published on

October 25, 2016

Category

Features

The genius of unsung electronic music pioneer Bruce Haack, as told by his friend and manager Chris Kachulis.

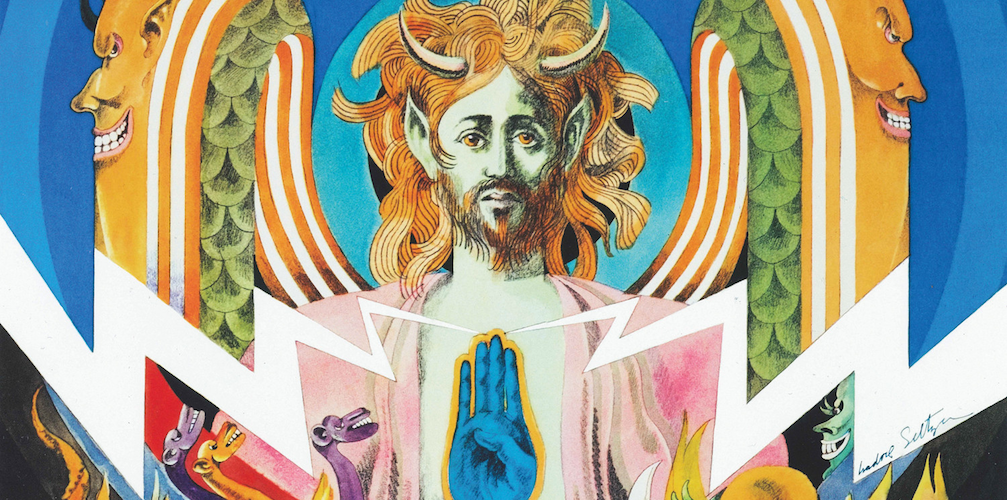

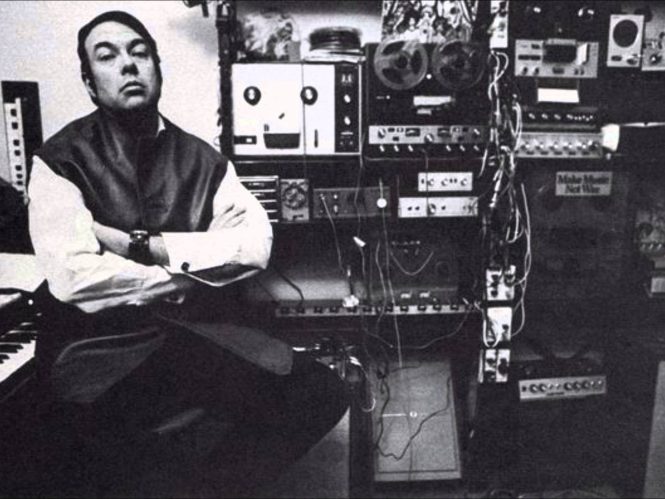

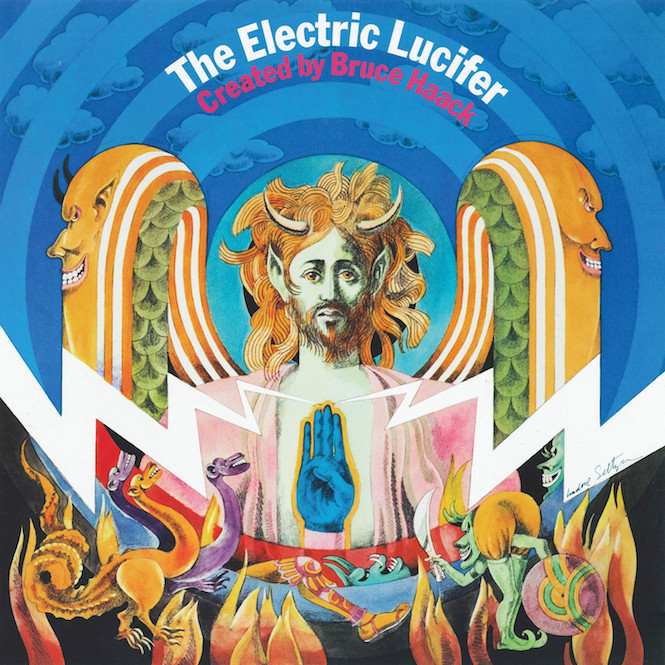

Bruce Haack was the quintessential under-appreciated pioneer in his lifetime. A prolific builder of his own homemade electronic music instruments, the Canada-born Haack turned his hand to scores of albums of music for children and advertising agencies as well as more mature works for choreography and orchestration. Resisting the confines of traditional musical education, Haack remained an outsider even as he used his inventions to create music aimed at a wider audience, but it was with 1970s The Electric Lucifer that he drew on the burgeoning alternative rock scene to create a visionary album that scored a major label release.

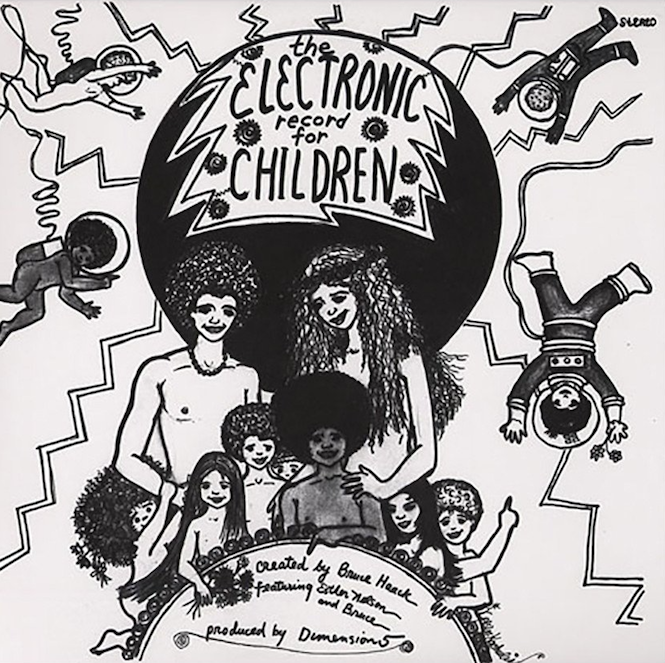

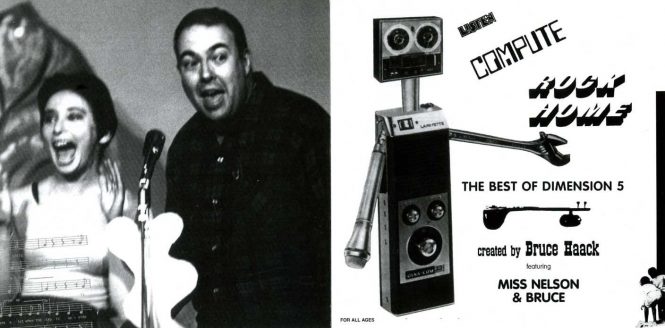

Alongside dance instructor Esther Nelson and lifelong friend and benefactor Ted Pandel he created Dimension 5 in the early ‘60s as a record label for releasing his many compositions for children. Meanwhile it was Chris Kachulis, a friend since the mid-fifties, who adopted an unofficial role as Haack’s business manager, helping to introduce his work to the booming advertising industry.

Kachulis also performed some of the vocals on The Electric Lucifer, and after the album’s completion was instrumental in securing a deal for the record with Columbia. With his work becoming more introverted (as heard on the posthumously released Haackula) Haack’s later life and productivity was blighted by his failing health. He passed away in 1988, having lived for some time in the family home of Ted Pandel in West Chester, Pennsylvania.

Following the recent reissue of The Electric Lucifer on Telephone Explosion Records, here Kachulis recounts his experiences of working with Haack through the ‘60s and ‘70s, in particular around the recording of The Electric Lucifer and its sequels.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fjsubxVYg2o

Beginnings

I first met Bruce in ‘58 when Ted Pandel introduced us. Bruce and he first met in 1954 when they were both registering to go to Juilliard Music School. A few years later I was working in the graphic arts department at American Broadcasting Company and Ted was there too. He said, “Let me introduce you to a terrific composer, lyricist and inventor of instruments.”

Ted and Bruce were both based in Manhattan just a few blocks from ABC, and one evening after work I went to their studio. Bruce was a great carpenter, so he extended his studio and he built an upstairs parlour even though it was on one floor. He created a sleeping area because he wanted to have more space to build his instruments.

I was amazed. It was so unusual and unique, the way he would record. He played me some of the things that he did, even before the Dimension 5 works had begun. He wrote a ballet and he used to do music for marionette window displays.

Straight away I started contacting advertising agencies to consider his work. I hand delivered audio cassettes with samples of his work to all the agencies on Madison Avenue. The first company to call would be J Walter Thompson, and he started doing commercials for them, but then it expanded after he did The Electric Lucifer. In a very relaxed and informal way I became Bruce’s manager, but the first thing that I really worked with him on was The Electronic Record for Children in 1969.

The first descent

When I used to meet with Bruce, I used to bring him vinyl recordings of a lot of the British bands of the era. He loved The Who, especially Tommy, and the Bee Gees concept works like Odessa. He didn’t care for disco much, but he loved James Brown and Janis Joplin. He loved the concept albums The Moody Blues did, but his favourite was Cream. He’d play them constantly, and he’d get stoned while he listened to them. He painted a whole ceiling of stars and the solar system on the ceiling, and on his wall he had cave paintings from the prehistoric times. He loved that because he could see aliens in the paintings.

When he played back recordings that he had done, he would have a special light setting, and that’s how people would sometimes hear his work for the first time. Of course the first person to hear his work would always be Ted Pandel because Ted was almost his benefactor, besides being a caring and a loving friend.

Bruce had had the idea for Electric Lucifer since the early ‘60s and started creating it between 1968 and ‘69. I think he finished it in ‘69. We used to take bus trips to small ocean towns on the Jersey shore, and then we’d start walking back towards the city. Sometimes we’d stop and go to a restaurant, and when we got tired we’d take the bus back to New York. All that time he was thinking of melodies and writing things down, and then when he got back home he’d record what he had come up with. That’s where the sixteen pieces that he did for Electric Lucifer were born, in those months walking right through the summer and into winter. He loved that combination of weather and ocean.

After it was finished and he was so happy with it, I said, “Let me try to find a label instead of putting it on Dimension 5.” I called John Hammond at Columbia and he said, “Give me a few months and call me back.”

After a few months I called John Hammond again and brought him Bruce’s original recording of Electric Lucifer, and he was very interested in releasing it on Columbia Records. I had to have a spokesperson, and a man called Jay Center was to be the agent for it. He had been the manager of Tony Taylor and Jon St. John who also sang on the album. Jay went and signed a deal and John Hammond gave him I think a $2000 advance, and then Jay Center disappeared with the money and we never saw him again, but that’s OK, the arrangement was still in effect.

Bruce had recorded the whole thing in his studio and produced it himself, but when we got the deal with Columbia Bruce was able to do some polishing in the CBS Studios. There was nothing new that was done, but Bruce wanted to put some Moog synthesiser in which he didn’t have at home, and I did some vocals at Columbia that he added.

The second (and third) coming

Everyone knows about Electric Lucifer Book 2, which he recorded in 1974, but there’s a Book 3 of Electric Lucifer called I.F.O. which he did right after he recorded the first album. Electric Lucifer was already going to be released and he was very happy with it, so he created the last part of the triptych of Electric Lucifer, before he did Book 2. Book 2 ended up containing some of the things that he did in Book 3, like ‘Stand Up Lazarus.’

He had the inspiration for the ending and he wanted to do it in the week between Christmas of 1969 and into the New Year 1970. He liked that transition into the new decade. Ted was away for Christmas with his family and I was with Bruce in the studio on 72nd Street over the Sacred Cow restaurant.

Identified Flying Object, that was supposed to be the subtitle of Book 3, and he created it in that period between Christmas Eve and New Years Day. I was with him the whole time, and after he finished it he was so happy, and we both got drunk and stoned.

The song ‘I.F.O’ itself goes: Is Jesus coming on a saucer? Or will he be coming out of the sea? Jesus could be coming from a way inside, you know Jesus he can set us free. Just before his miracle awakes us, we might see a flash of ruby light. Some might play guitar and some a computer, and some will try to jump out of sight.

Bruce was interested in all religions. I don’t know if he was a believer but he was inspired because he loved the drama of the church. He thought it was great theatre. The basic message is, not from the sea, and not from the saucer, but from inside you. It doesn’t have to be a major religion.

A legacy (of sorts)

Around 1971 Ted got his professorship at West Chester University in Pennsylvania, and he asked Bruce if he wanted to come. Bruce was alone then in Manhattan. I was working with Bruce, but Bruce was very depressed because he wanted to get closer to Ted. Less than a year later Ted had Bruce come to Pennsylvania from New York City and that’s where he lived for the rest of his years. He had a good life there and he had some degree of quality and comfort.

Electric Lucifer Book 2 was put together in 1974, but it never got released. In 2001 a German label bootlegged the work on a compilation with some of his children’s music, saying they couldn’t find Ted or myself. Later on he couldn’t release Haackula because the labels didn’t care for the language and the homoerotic overtones.

Around 2003 Philip Anagnos made a documentary called Haack: The King Of Techno. A couple of years later he and I did a video where I lip synched all the songs I did with Bruce on Book 3, moving from Bruce’s old studio on 72nd Street into the subway and winding up in Central Park. The whole thing was done in 43 minutes in real time, but nothing was ever done with that video. I think Ted has a hard copy of it somewhere.

After Bruce died in 1988 Ted became the executor of his estate, although it doesn’t really mean much because there’s no major income from that. Not enough people know him. As Bruce always said, “Whoever wants to know me will find me.”