Boston’s creative jazz scene: How the ’70s avant garde found a home outside New York City

The ’60s and ’70s were among the most fiercely creative in the history of jazz, a time when politics and free improvisation coalesced in basements and lofts across America. Too often though, the story is confined to New York City.

With a new compilation out now on Cultures Of Soul, we publish an extract from the accompanying book, tracing the roots of jazz in Boston and the major players in one of the country’s most innovative, tight-knit scenes.

Words: Mark S. Harvey

JAZZ IN BOSTON

While the epicenter of the avant-garde movement was split between Chicago and New York, Boston may justifiably lay claim to a significant contribution in terms of people, places, and scenes that developed in the old Puritan colony. To tell this story I will first sketch a bit of Boston’s jazz history and then move on to a consideration of the avant-garde scene in the 1970s.

Boston has always had a fertile indigenous jazz scene as well as a welcoming climate for traveling performers, thanks to its neighborhood clubs, large ballrooms, and other venues such as Symphony Hall and beyond. In the 1920s, talented musicians such as alto saxophonist Johnny Hodges and baritone saxophonist Harry Carney developed their craft in Boston and then joined pianist and composer Duke Ellington. Throughout the Swing Era, all of the “name” big bands played throughout the area, Newton-born composer-arranger Ralph Burns contributed harmonically advanced charts to the Woody Herman Orchestra, and pianist Sabby Lewis led one of the best Boston-based orchestras.

Stanton Davis

By the 1950s, new creative tendencies were on as display as pianist-composer Jaki Byard led his own forward-looking small and big bands at Wally’s while pianist-composer-arranger Nat Pierce led his own stellar groups around town when not on the road with Woody Herman. Reflecting the influence of bebop, luminaries such as trumpeters Herb Pomeroy and Joe Gordon, along with baritone sax master Serge Chaloff, alto saxophonist Gigi Gryce (a student at Boston Conservatory of Music), and pianists Dick Twardzik, Toshiko Akiyoshi, and Jaki Byard among many others, plied their creative trade at the legendary Stable and George Wein’s Storyville, which were across the street from each other near Copley Square. Pomeroy, with alto saxophonist Charlie Mariano, pianist Ray Santisi, and tenor saxophonist Varty Haroutunian, originated the original Jazz Workshop, an early performing and educational program at the Stable, whose leaders became the core of the Berklee School (later Berklee College) of Music faculty. Other standout musicians working at the cutting edge of modern jazz were tenor saxophonist Sam Rivers and trumpeter Don Ellis, who were both graduates of Boston University, pianists Chick Corea and Hal Galper, and drummer Tony Williams, who was well known and respected throughout professional circles before his 18th birthday. By the mid-1960s, all of them had left for New York City and established associations with leading performers of the period.

The Year Of The Ear live in Copley Square

In terms of venues, a lively club scene in the 1950s and 1960s, which ran along Massachusetts Avenue and continued into the South End on Tremont Street and Columbus Avenue into Roxbury, drew committed fans to nightspots such as the Savoy, the Hi Hat, Estelle’s, Connolly’s, the Pioneer Social Club, and the perdurable Wally’s Paradise, which is still going strong after 70 years. By the 1960s, however, many of those clubs were in decline or had been shuttered. Yet new venues like Fred Taylor’s Jazz Workshop and Paul’s Mall on Boylston Street as well as Lennie Sogoloff’s eponymous Lennies-on-the-Turnpike out in West Peabody shored up the scene. Another North Shore venue was Sandy’s Jazz Revival in Beverly, where Sandy Berman continued a family tradition of presenting the best in jazz.

The Year Of The Ear live in Copley Square

The area’s largest newspaper, The Boston Globe, sponsored a major jazz festival annually, continuing an earlier festival tradition in town. (It is worth noting that the granddaddy of all festivals, the Newport Jazz Festival, which began in 1954, was the brainchild of Boston impresario George Wein and has maintained a strong Boston connection over many decades.) The inauguration of a jazz program at the New England Conservatory in 1969 complemented the steady growth of the Berklee School of Music throughout the ‘50s and ‘60s. Both institutions offered faculty and student concerts that represented a shift in the nature of jazz programming from club dominance to a mixed bag of presenters.

All of this is a concise summary of what most local jazz aficionados, with justifiable pride, take to be the narrative of how the Boston scene evolved. However, alongside the impressive roster of notables and venues mentioned above, most of whom worked and presented music largely in the jazz mainstream, there were others interested in different approaches. These musicians, their music, and their presentational contexts constituted a parallel line of development within the scene, one that is often overlooked.

Lowell Davidson with Keytar

THE BOSTON AVANT-GARDE

The Pathfinders

By the 1950s, there was a small cadre of individualists in town exploring new directions in jazz and improvised music, although most of these players are now forgotten. Bassist John Voigt has called these pioneers the “ghosts” of an incipient scene. The most notable of these individuals is Major “Maj” McCree, an alto saxophonist who also played trumpet and experimented with electronic music.

One of the most significant individualists in this group was Cecil Taylor. In 1953 Taylor graduated from the New England Conservatory’s Department of Popular Music, where he was exposed to a wide variety of musical styles and sounds, including those of European modernists such as Bartok and Stravinsky. His wide-ranging aesthetic palette, which was later broadened by influences from modern dance and other contemporary art forms, foreshadowed subsequent generations of improvisational explorers who would draw inspiration from myriad sources beyond jazz.

Taylor’s improvisational style was incubated at the Conservatory, where he experimented with the building blocks of scales and chords, and, as he said, “just combinations of tones, and then just intervals spaced differently, not scales at all, just groups of notes.” Although he moved back to his hometown, New York City, following graduation, he returned to Boston in the fall of 1956 to record his first record on the Transition label. Harvard graduate and jazz enthusiast Tom Wilson started his short-lived Transition Pre-Recorded Tapes, Inc. in 1955, but by 1957 had run out of funds to continue operating. Yet in those three years, Wilson had released albums by the Jazz Workshop Quintet, Dixieland players, tenor saxophonist John Coltrane in his hard bop phase as well as trumpeter Donald Byrd, and the first recordings by both Sun Ra (Jazz by Sun Ra, reissued as Sun Song) and Cecil Taylor.

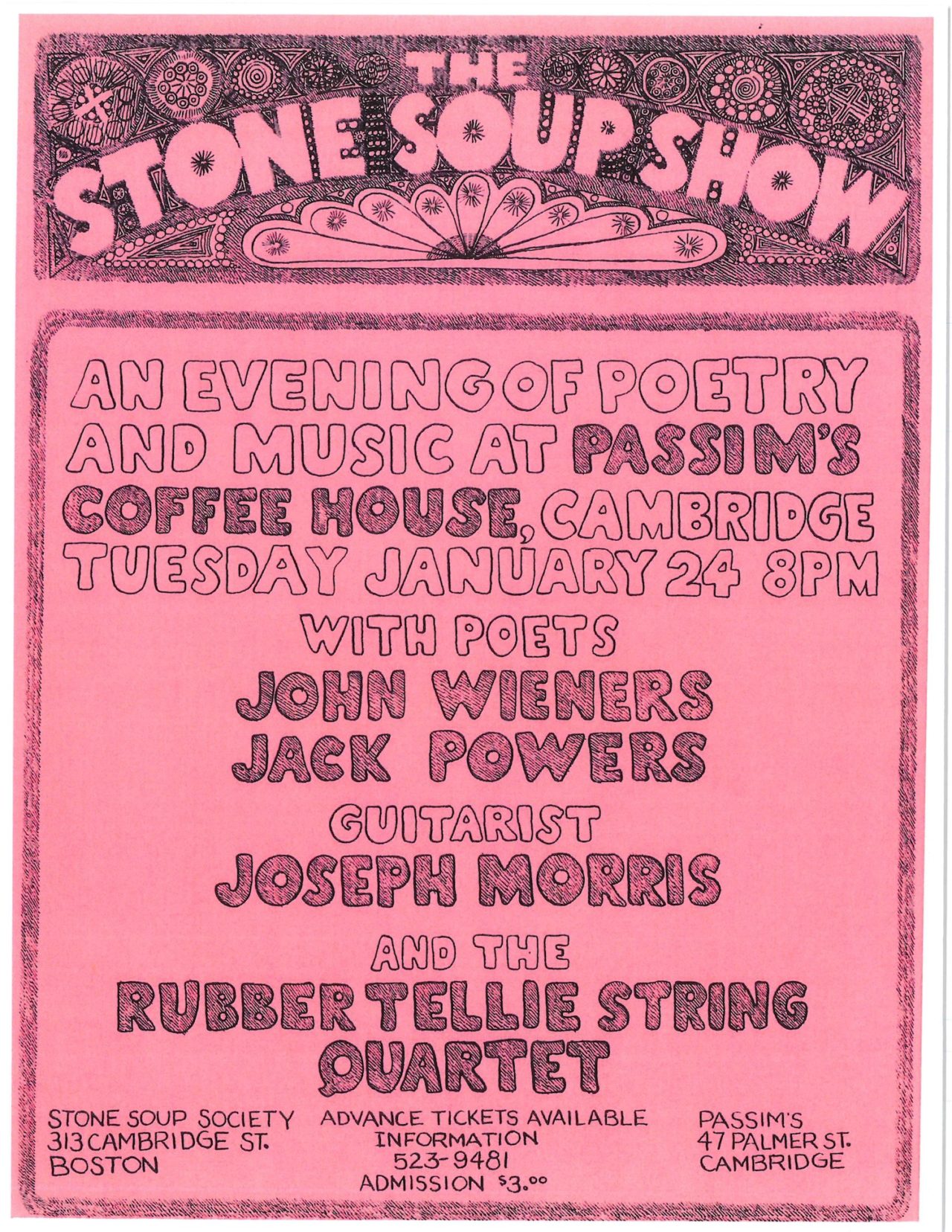

Gig flyers

Taylor’s inaugural album, Jazz Advance, featured Steve Lacy on soprano saxophone, Buell Neidlinger on bass, and Dennis Charles on the drums. The music clearly shows Taylor’s consolidation of techniques and ideas he encountered earlier but cast in a personal stylistic approach. It thus remained wholly original and extremely demanding of the listener. Nat Hentoff, writing in liner notes to the reissue of Jazz Advance, said that “Listening to Cecil is a catharsis….the deep exploding sense of natural forces at work…this is music based on elemental energy.” And according to Taylor himself, “Part of what this music is about is not going to be delineated exactly. It’s about magic, and capturing spirits.” While the music on Jazz Advance doesn’t show the fully realized sense of volcanic tumult of his later work, it is nonetheless revolutionary in its expression and remains all about challenging and subverting the common practice harmonic system of jazz. While there is some use of head-solos-head formats and playing over time, along with arrangements of compositions associated with Duke Ellington and Thelonious Monk, chord changes are largely obscured if not often abandoned in favor of linear complexity and textural density. And when terms such as “elemental energy” and “capturing spirits” were introduced into the descriptive lexicon of terms for improvisation, it was clear that something fundamental had changed. Cecil Taylor is significant as both a founding father of the jazz avant-garde and arguably Boston’s first documented avant-gardist, although he spent only a few years in town.

The other major figure of the 1950s Boston avant-garde scene was Boston native Ken McIntyre (later Makanda Ken McIntyre, 1931—2001). By 1959, he had earned both bachelor’s and master’s degrees in music composition from the Boston Conservatory of Music. Richard Vacca has succinctly documented his early career activities:

“McIntyre’s best-known Boston group was a 1960 quartet with trombonist John Mancebo Lewis, bassist Larry Richardson, and drummer Bill Grant. While still in Boston, he took part in two recordings for Prestige New Jazz in the spring of 1960, Looking Ahead with Eric Dolphy, and Stone Blues, with his own group of Lewis, pianist Dizzy Sal, bassist Paul Morrison, and drummer Bobby Ward. He moved to New York in spring of 1962.”

Boston jazz journalist John McLellan described a McIntyre gig this way: “The music these men play is full of surprises, shocks, and delights. Unusual construction of tunes, varying rhythmic patterns, and above all an emphasis on complete freedom of improvisation are the characteristics most immediately noticeable…these musicians are going to change the sound of jazz.

Thing in performance

The music of both Taylor and McIntyre was controversial, often drawing the ire of established mainstream musicians and critics. McLellan, in the same review quoted above, while open to what was being attempted, pulled no punches, calling McIntyre’s music “tortured on occasion, too intense…even immature.” This type and tone of criticism would consistently dog McIntyre, Taylor, and others of the avant-garde movement. McIntyre had followed Cecil Taylor’s example, leaving Boston for New York to further his career. Yet it is clear that for both artists, this city provided the context for their formative creative work while their pioneering efforts set an example for those that followed.

The Boston Creative Jazz Scene 1970-1983 is out now on double vinyl, including the 80-page book from which this extract is taken. Click here for more info.