An introduction to John Carpenter in 10 records

John Carpenter is the hugely influential composer behind the original sound of Halloween. In this record-by-record guide, Nick Soulsby breaks down just how he makes the synth stabs that send shivers down your spine.

The best horror movies allow the imagination of the audience to fill in the blanks and bring the unseen to life. John Carpenter, from his earliest days, has wedded his films to compelling soundscapes, knowing that it’s the audio accompaniment that will allow his visuals to pierce the mind’s eye most deeply.

With his Anthology: Movie Themes 1974-1998 retrospective out now on Sacred Bones, we look at ten highlights from Carpenter’s catalogue of horrors, all of which are possible reasons perhaps why Trent Reznor of Nine Inch Nails recently felt moved to declare: “John Carpenter, it’s your fault that I turned out the way I did.”

John Carpenter

Halloween

(Columbia, 1979)

While Halloween was the greatest (and most enduring) success capping the first decade of Carpenter’s career, it was also the very first time one of his soundtracks was officially released. The ‘Main Theme’ to Halloween was a culmination of approaches he had developed to summon up uncanny and relentless tension and threat.

The high-pitched, swiftly fingered cycle of notes underpinned by a pulsing drumbeat; the heavy plod of the keyboard fanfare with its uncomfortable, intensifying trajectory; how the doubled sound gives every chord an unsettling twin; the way in which, at points, everything is suddenly silenced to leave just the original cycle stark and exposed.

Carpenter follows this model in many of his soundtracks, where structures are built, dismantled, and toyed with in varying terms of speed, attack, and instrumentation – the known rising up in a corrupted and a discomforting form.

John Carpenter

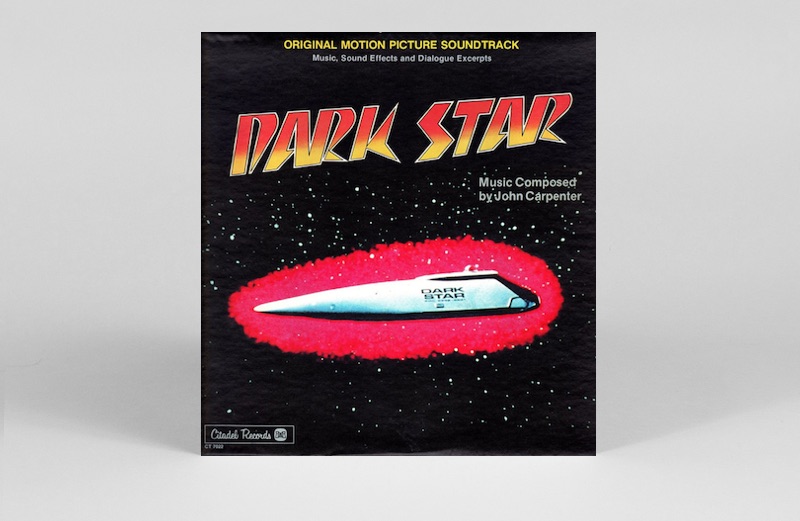

Dark Star

(Citadel, 1980)

A suite composed by Carpenter then arranged, produced and performed by his collaborator Alan Howarth, the music to Dark Star was released as two undifferentiated sides listed simply as ‘Music, Sound Effects And Dialogue Excerpts Part 1/Part 2’ in the wake of the success of Carpenter’s film Halloween. A limited edition release in 2012 condensed this down to 11 specific tracks.

The ‘Dark Star’ theme is a thick-fingered anthem, hammering home the same slow chords on two synthesisers in slightly different settings to create discordance — a strong hint at how the BBC Radiophonic Workshop would use keyboards to replace their more esoteric methods. Tracks like ‘Pinback and the Mascot’ move from call-and-response — between brief phrases played on a synthesiser, and improvised sound effects mimicking mechanical or alien sources — to tweaked echoes of the opening theme.

John Carpenter & Alan Howarth

Escape From New York

(Varèse Sarabande, 1981)

This soundtrack straddles two genres, both reflected in the musical score. On the one hand, there’s the high-tech military future war aspect, on the other there’s the portrayal of NYC (then buried in its lengthy post-bankruptcy spell of urban blight) as a derelict zone abandoned by civilisation, filled with prisoners left to rot. The former is visible in the gleaming, tightly clipped and methodical machine-gun tap of a track like ‘Over The Wall/Air Force One’ while the latter can be seen in the barren menace of ‘“Don’t Go Down There!”’ or ‘The Duke Arrives/Barricade’.

Notably, the swagger of Kurt Russell’s character Snake Plissken appears at times as funky guitar licks or bass rhythms. Carpenter has always been hyper-aware that while a full band sound or dense composition might have impact, a single sound in isolation, allowed to resonate amid emptiness, has an uncanny effect on the ear, and makes each movement — whether the entry of a high-pitched tone, or a change of pace or rhythm — feel deeply dramatic.

John Carpenter & Alan Howarth

Halloween III: Season of the Witch

(MCA, 1982)

Carpenter’s work on Halloween III is peppered with sounds recognisable from early computer games, a genre that his own work had (and would) influence. The ‘Main Theme’ emblazons electronic chirruping over glowering tone-washes, while both ‘Chariots of Pumpkins’ and ‘First Chase’ jab relentlessly with sharp, almost painfully high-pitched keys. The latter breaks into one of Carpenter’s signature synthesiser vamps to lend urgency and pressure — the repeating sequences seem to mess with perception of time giving everything a breathless pace.

‘Halloween Montage’ is the most recognised piece of music from the film: a jaunty (and mercifully brief) advertisement slot from the Silver Shamrock company, in which pixie-voices count down the time left until Halloween to the tune of ‘London Bridge Is Falling Down,’ impersonated on an electronic pipe-organ. As a composition, it matched the film’s theme of childhood being attacked, manipulated, and made into something impure.

John Carpenter

The Fog

(Varèse Sarabande, 1984)

The original 1980 score cues to this tale of revenge from beyond the grave are a highlight in Carpenter’s discography. The artificial tones of the synthesiser are used sparingly and precisely with centre stage belonging to an appropriately haunting piano from which notes fall and pauses echo into silence, as bass notes rumble in the background like encroaching storms.

Carpenter used the incongruity of a mid-pitch sinewave (particularly out of place when placed against the backdrop of the seaside town location of the film) to indicate the presence of the supernatural, and he returns to it throughout the cues with the same effect Spielberg sought with the Jaws theme: a sense of being hunted, of proximity to death.

Death itself arrives as a burnt-edged crash of violent static blasting all else aside. On ‘Where’s The Seagrass?’ the metallic ting of a synthesiser effect works at the nerves until the piano returns to walk up and down a nagging chord pattern that reoccurs in spindly fashion on ‘Stevie’s Lighthouse’ or sped up on ‘Something To Show You’. The soundtrack is a startling example of what, today, would be seen as a dark ambient composition but which, then, there was no word for other than ‘eerie’.

John Carpenter & Alan Howarth

Prince of Darkness

(Varèse Sarabande, 1987)

While the film was relatively poorly received, Carpenter’s ongoing collaboration with Alan Howarth yielded yet more gloriously strange harvests on this soundtrack. Satanic choirs? Check! Discordantly demonic background sounds? Check!

But there’s more. While drawing in a couple of the tropes of the Satan-inspired horror film, the two composers still created something that meshed with their own wider sound world. What’s interesting is the focus at numerous points on the foot-stomping heaviness that stands out from the mix, whether in the form of a pumping four-four rhythm, or steady deadened thuds shaking the air.

There’s also a tendency to make moves that wouldn’t be out of place on Coil’s Hellraiser themes: a sudden shattering crash of glass-fragile keyboards, a two-note sequence gradually buried in howls and screeches, as what sounds like sampled opera vocals warble and twist in the background. There are few true respites from the shadows and darkness at any point in this immersive recording.

John Carpenter & Alan Howarth

They Live

(Enigma, 1988)

The sultry sunburnt sway of ‘Coming To LA,’ with its wailing saxophone and mouth organ refrain sets just the right twisted mood: the sheriff comes to clean up the town but the town in question turns out to be high-gloss eighties Hollywood, and the hero is a former pro-wrestler.

Music (and Carpenter’s film budgets) had moved on significantly, and this soundtrack is saturated with signs of that time. On ‘The Siege of Justiceville’ there’s a newly pumped muscularity to the synth stabs, a sharp pop and click to the rhythm track before the cunning entry of a military drum tattoo overwhelms the song. As ever, Carpenter has a film-maker’s eye for associating sounds with individuals (elements of ‘Coming to LA’ play through any track focused on the hero), then weaving the familiar back in amid fresh elements and tweaked contexts. The finale, ‘Wake Up’, tears up the steady roll of the record to replace it with a quick-fire and appropriately disjointed clash of sparse, echoing disquiet, and brutally cut-off tunes.

John Carpenter

Sentinel Returns

(Player One, 1998)

A lesser known work in Carpenter’s discography is the soundtrack called Earth/Air he created for this 1998 PlayStation/PC game. In their most soaring moments, the synth pieces here arrive close to Jean-Michel Jarre’s work, marrying recognisable melodies to the synthesiser’s ability to stretch and sustain sounds. At times the drum machine elements sound very much of their time — excessively clipped tapping, the puffs of air that passed for a snare, random whoops and new age star-glitter effects — but that doesn’t detract from Carpenter’s ability to evoke atmospheres of triumph and dread.

In comparison to many of his works, the mood is relatively light, and he uses a broader palette of piano, gong, xylophone, and what sounds like the bell on an old-fashioned bus or San Francisco tram. There’s even a track that seems to combine motifs from various of his best-known works, featuring the hyper-nervous piano chords of Halloween alongside the shaking, shivering maraca(like) sound of Assault On Precinct 13.

John Carpenter

Assault On Precinct 13

(Record Makers, 2003)

Carpenter’s score for this 1976 film works in the same realm as his horror soundtracks to emphasise the presence of danger, the remorselessness of the enemy, the sombre tension hanging on the victims.

With a limited range of tools and capabilities, Carpenter’s approach (with Alan Howarth performing and arranging) was to use the restricted palette to tie certain sounds to particular characters: the skittering metallic drum machine and heavy drones representing the gang members; a moody electric piano following the lawman who ends up holding together the fragile defence; the eeriness of the ice cream chimes marking the shocking death of a young girl that provokes the spiral of violence; high pitched whines indicating the sharp sting of death is moments away.

The refashioning of these elements into separate cues and components never feels repetitious: the knife-edge emotion never lets up.

John Carpenter

Lost Themes II

(Sacred Bones, 2016)

Opener ‘Distant Dreams’ hammers in on live-sounding drums and synthesiser wielded like industrial guitar, trashing the idea that Carpenter could only make spiralling soundtrack music. ‘Dark Blues’, similarly, rips out a mash up of eighties hard rock over anxious keyboards, while bonus track ‘Real Zeno’ goes even further with some gloriously dirty, palm-muted guitar licks and devilishly distressed organ.

On the other hand, both pieces are atypical of a record that stays happily rooted in familiar electronic territory (the run of two word titles — ‘Utopian Façade’, ‘Windy Death’ — speak to the same apparent comfort level).

Maybe it’s the absence of a visual scene with which to associate each track, but the heart-in-mouth aspect of Carpenter’s finest work is absent — it’s hard even to imagine what film concepts might align to these themes.

In truth, what it emphasises is how intimately entwined the two aspects of Carpenter’s art are. Without the narrative and visual elements, the music lacks bite, but then, by the same virtue, it’s unthinkable that Carpenter’s films would possess their iconic intensity and urgency without his musical compositions keeping their edge razor-sharp.